Kane pulled from the oeuvre of John Kacere for his S/S18 show, Domestic Services

Christopher Kane’s S/S18 show, Domestic Services, was brimming with the doily-adorned kitchiness and domesticity of British suburbia. “I have always been obsessed by that pristine woman, so clean, so proper, yet having an emotional breakdown inside,” read the show notes. This woman’s penchant for the spic-and-span emerged via ready-made details straight from the kitchen sink: from mop head-fringed ankle boots to sponge-trimmed shoes, right down to a washing machine-print T-shirt complete with dangling J-cloth. In a bid to excavate this housewife’s latent disquiet, there was an overt play on kink too. Between allusions to this season’s muse, Streatham sex party queen Cynthia Payne, were direct references to the very singular work, and perhaps mind, of American Photorealist painter John Kacere. Working with the Louis K Meisel gallery, holders of the largest collection of Kacere’s work, Kane plastered imagery from the late artist’s oeuvre of lingerie-clad bottoms across frilly nighty-like T-shirts, complete with ‘Kacere’ emblazoned across them.

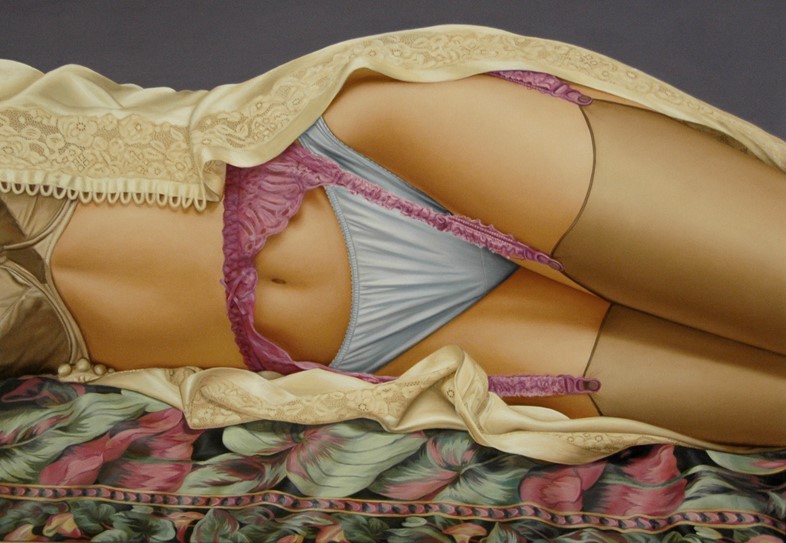

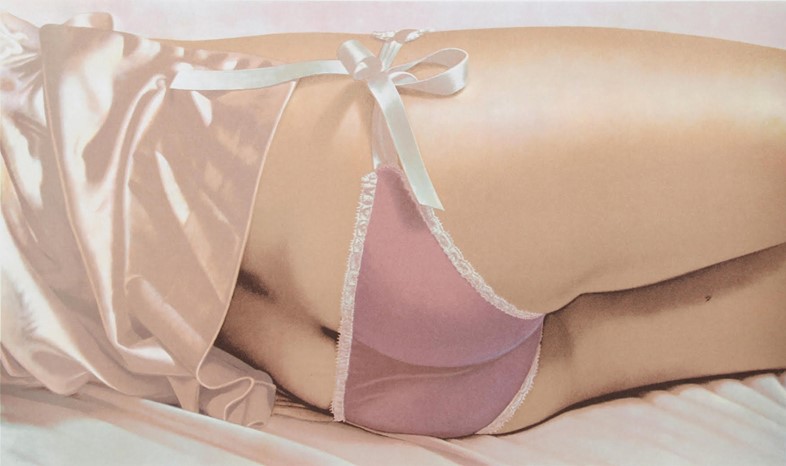

Born in 1920 in Iowa, Kacere is known for his ultra large-scale paintings that focus almost exclusively on the contours of the mid-section of a woman’s body. In 1967 he was captivated by a painting of Pop Artist Mel Ramos’, named Beaver Shot, of a fully-clothed woman whose dress bore a hole that mysteriously, and neatly, revealed her white cotton pants and crotch. Having previously dabbled in Abstract Expressionism, Kacere began painting from photographs that zeroed in on this very specific subject matter and composition. According to art dealer and author Meisel, such specification “lead to what became one of the most unique subject matters for any Photorealist.” Meisel, who named the genre in 1969, has since documented and exhibited almost all of Kacere’s works and included him in his three weighty volumes on Photorealism. “I was granted rights to publish, present and promote his work in any way I can,” he tells AnOther. “The Kane usage is just one more way of having the world know and remember John Kacere.”

Kacere captured the glossy ripples of silk slips, the gossamer glow of gauzy briefs, the scrunch of a clipped suspender and the intricacies of lace hold-ups – all to exquisite detail. This fixed gazed garnered the painter much attention from the 60s onwards and inspired numerous copy cats. Sofia Coppola even acknowledges referencing his work in that alluring opening shot of Scarlett Johansson’s sheer pink briefs in Lost in Translation. Though Kacere briefly experimented with painting full-body compositions during the 80s, he rather quickly returned to his money shot; this singularity pitched his work as an iconic representation of the movement. Upon regarding a swathe of his paintings in this repetitive pose, the headless female body is almost abstracted, while these codes of idealised femininity begin to appear alien. “Realism consists of portrait, still life and landscape. Many see all three in Kacere’s paintings. Portrait, still life and yes, even landscape,” Meisel explains.

Of course, such subject matter quickly engaged the attention of second wave feminists in the 60s, prompting Kacere to respond with an arguably misplaced admiration for the female race. “Woman is the source of all life; the source of regeneration,” he said by way of defence. “My work praises that aspect of womanhood.” Maybe he was alluding to Gustave Courbet’s L’Origine du Monde – the French artist’s 19th century painting that candidly saluted the vagina as the origin of the world – offering us a trussed-up, silky-skinned version of this monumental work. An oxymoron, perhaps. Regardless, Kane’s use of Kacere’s paintings today, amid his tongue-in-cheek warped femininity, offers a fresh perspective.

John Kacere’s works are available at RoGallery, Louis K. Meisel Gallery and Ackerman's Fine Art, New York and Plus One Gallery, London.