Louise Dahl-Wolfe’s dynamic work paved the way for a generation of fashion photographers, and at a time when women rarely did so, as a new London exhibition attests

Female fashion photographers have often been eclipsed throughout history by their male counterparts, but Louise Dahl-Wolfe was at the vanguard of her craft for the entire duration of her career. Not only was she reponsible for creating the image of an independent and modern woman in the mid-20th century, when such a thing was still considered a novelty, but her photographs have since influenced countless successors. The American photographer is best known for her monopoly over the imagery of Harper’s Bazaar for her two decades as its staff photographer, where she worked under the legendary triumvirate of editor Carmel Snow, art director Alexey Brodovitch and closely with fashion director Diana Vreeland.

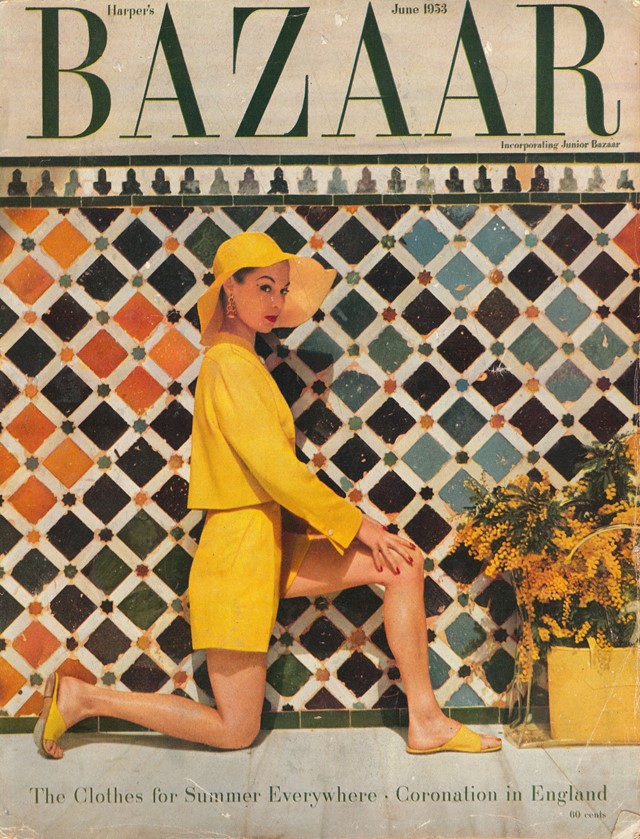

Today, the first retrospective of her work to be staged in the UK opens at London’s Fashion and Textile Museum. The exhibition comprises works from across Dahl-Wolfe’s extensive oeuvre; it includes a selection of the 86 covers she shot during her tenure at Harper’s Bazaar, between 1936 and 1958, but it also celebrates the less recognisable documentary photography which launched her career, and her lauded portraits of the likes of Jean Cocteau, Orson Welles, Bette Davis, Edith Sitwell, Vivien Leigh and Veronica Lake.

Defining Features

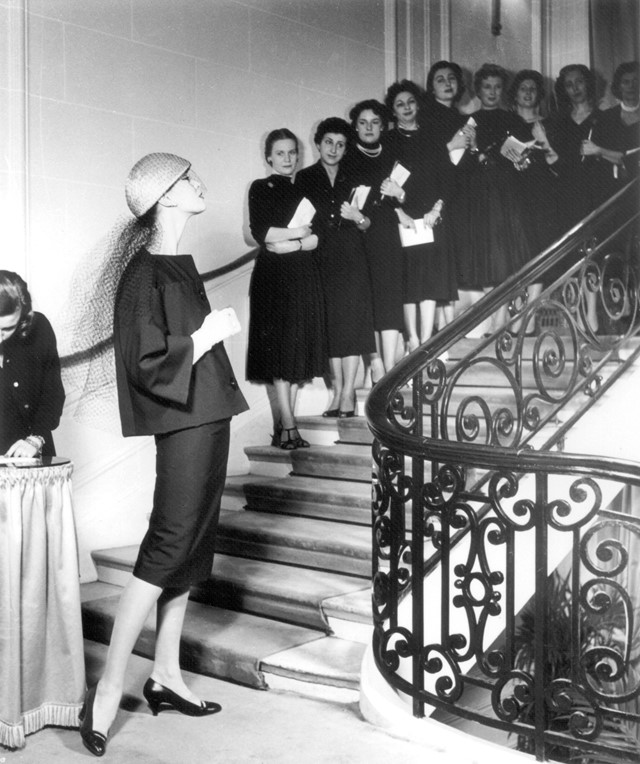

In her later life, the demanding yet down-to-earth Dahl-Wolfe was well-known for her chubby cheeks, dark hair scraped tightly into a bun glistening with beeswax, and the discerning looks she gave through her thick spectacles. Only on rare occasions was the photographer the subject of her own work, spending the majority of her time behind the camera lens rather than in front of it. Behind it, she was a trailblazer; her style marked a shift away from the stiff and static society portraits taken by the pictorialists who had preceded her in the 1920s.

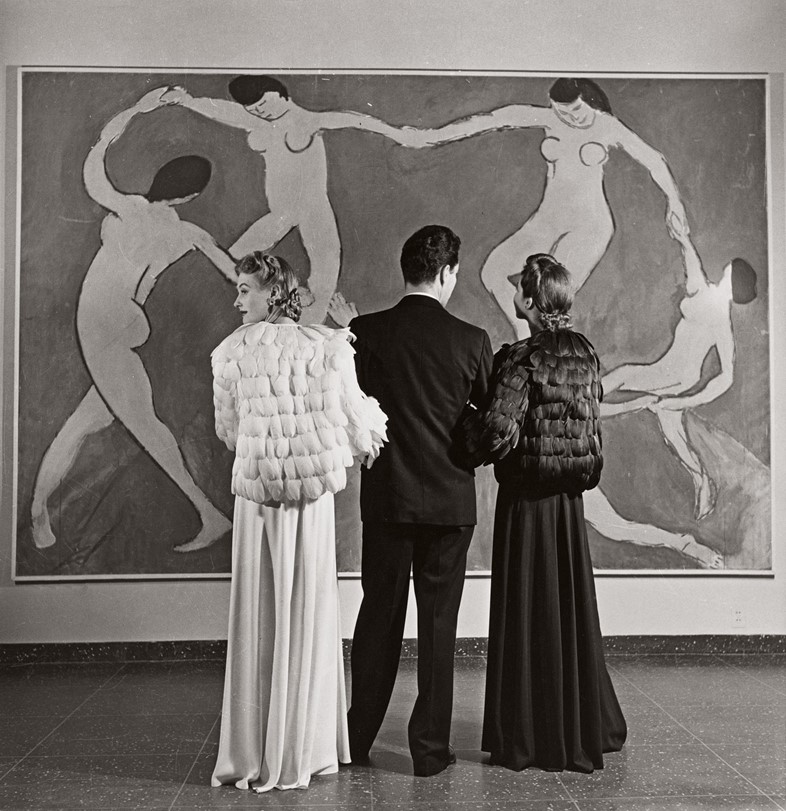

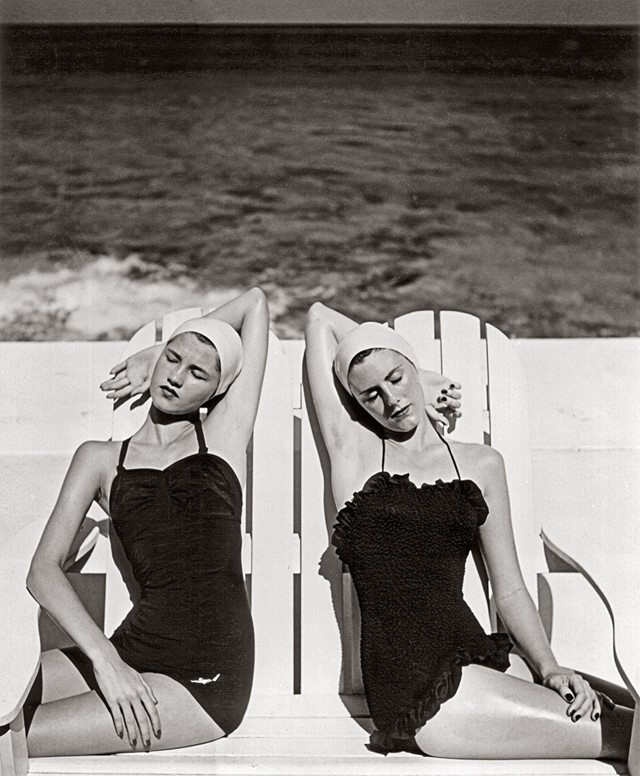

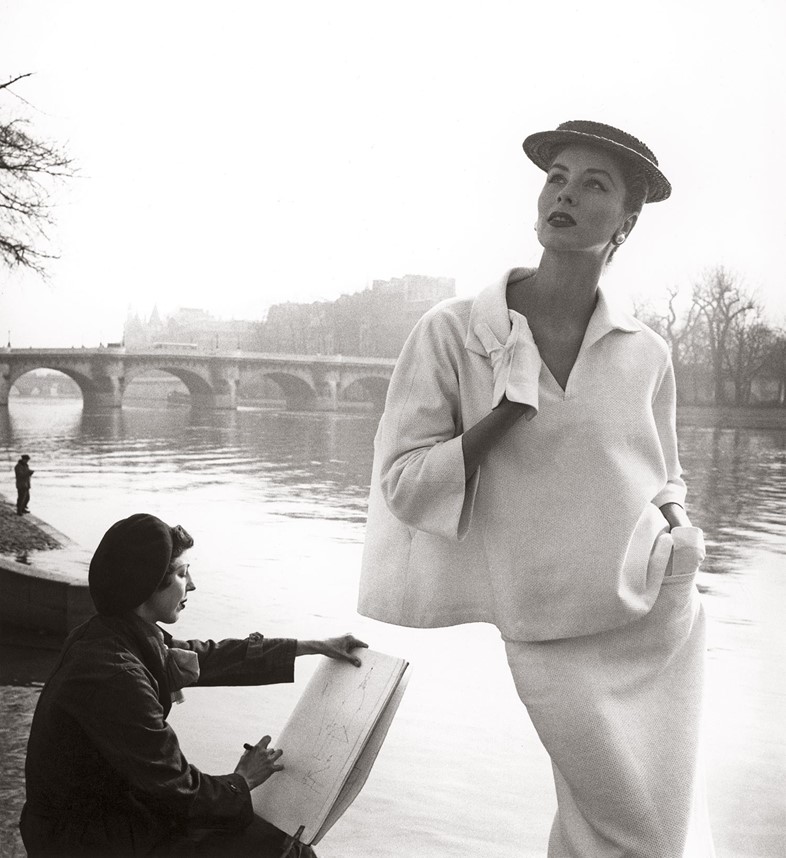

She was greatly influenced by Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes and the art of the Impressionists, which she first encountered at the World’s Fair held in San Francisco in 1915, and as such, Dahl-Wolfe’s images are imbued with a certain nonchalance. Her women presented a counterpoint to the austere, passive mannequins in the pages of the magazines; instead, these were modern models – dynamic, energetic and full of life. They were dressed not only in European couture (think: Balenciaga, Chanel and Dior) but in the ready-to-wear American sportswear of Clare Potter and Claire McCardell, and played a key role in bringing about what fashion historian and curator Valerie Steele termed “the American look”.

Dahl-Wolfe was also one of the first photographers to work in colour film, conducting her first experiments with Kodachrome in 1937, with an approach informed by her study of painting and colour theory. Following closely in the footsteps of Martin Munkácsi, she was insistent in taking fashion photography out of the traditional studio setting and onto the street, into natural light and on location both inside and outside the US, and soon became a purveyor of what became known as “environmental” fashion photography. In her innovative use of the medium, Dahl-Wolfe was the personification of the modern, liberal, active post-war women she was intent on capturing.

Seminal Moments

The Art Directors Club of New York acknowledged the innumerable iconic images Dahl-Wolfe lensed, and her seminal use of colour, presenting her with a medal in 1939, followed by an award in 1941, but her achievements reach far beyond her technical prowess. For one, Dahl-Wolfe was instrumental in creating the first generation of supermodels; she worked with the likes of Jean Patchett, Evelyn Tripp, Mary Jane Russell and Suzy Parker over the course of her career, and rather than standardising her models’ images she helped them create individual characteristic looks, which distinctly defined their professional careers. All the same, she was stubbornly principled; in 1946 she notoriously turned away a 15-year-old Carmen Dell’Orefice for being too young. As the story goes, she lead her to a window, closely inspected her eyelashes for proof, and then scolded her for wearing make-up. (That Dell’Orefice’s high cheekbones would appeared on the cover of Harper’s Bazaar’s rival publication, Vogue, not long afterwards, does not bear speaking about.)

She is also widely credited with launching the career of actress Betty Perske, who would later become Lauren Bacall. The March 1943 cover of Harper’s Bazaar featured a 17-year-old Perske, and caught the attention of director Howard Hawks, who suggested she change her name to Lauren Bacall and then cast her Marie ‘Slim’ Browning alongside Humphrey Bogart in the 1944 film To Have and Have Not. The film catapulted Bacall to star status in the Golden Age of Hollywood, and she went on to appear in films including The Big Sleep (1946), How to Marry a Millionaire (1953) and Murder on the Orient Express (1974).

She’s an AnOther Woman Because...

Dahl-Wolfe left Harper’s Bazaar soon after Snow and Brodovitch’s departures in 1958, when the magazine’s new art director attempted to direct her on set. It is an apt representation of her singlemindedness and strength of spirit (instead, she went on to to shoot for Vogue and Sports Illustrated, before retiring altogether from photography in 1960). And what strength of spirit was required for Dahl-Wolfe to do what she did; she was one of the very first fashion photographers as we know them today, an anomaly at a time when women were still often considered subordinate to their male counterparts. Not only did her dynamic style have a powerful impact on the imagery of successors from Irving Penn to Richard Avedon, but under editor Snow’s command, Dahl-Wolfe exploited the freedom she was given, breaking down constructed gender stereotypes of women in her imagery, both in America and further afield.

Louise Dahl-Wolfe: A Style of Her Own is on at the Fashion and Textile Museum, London from October 20, 2017 until January 21, 2018.