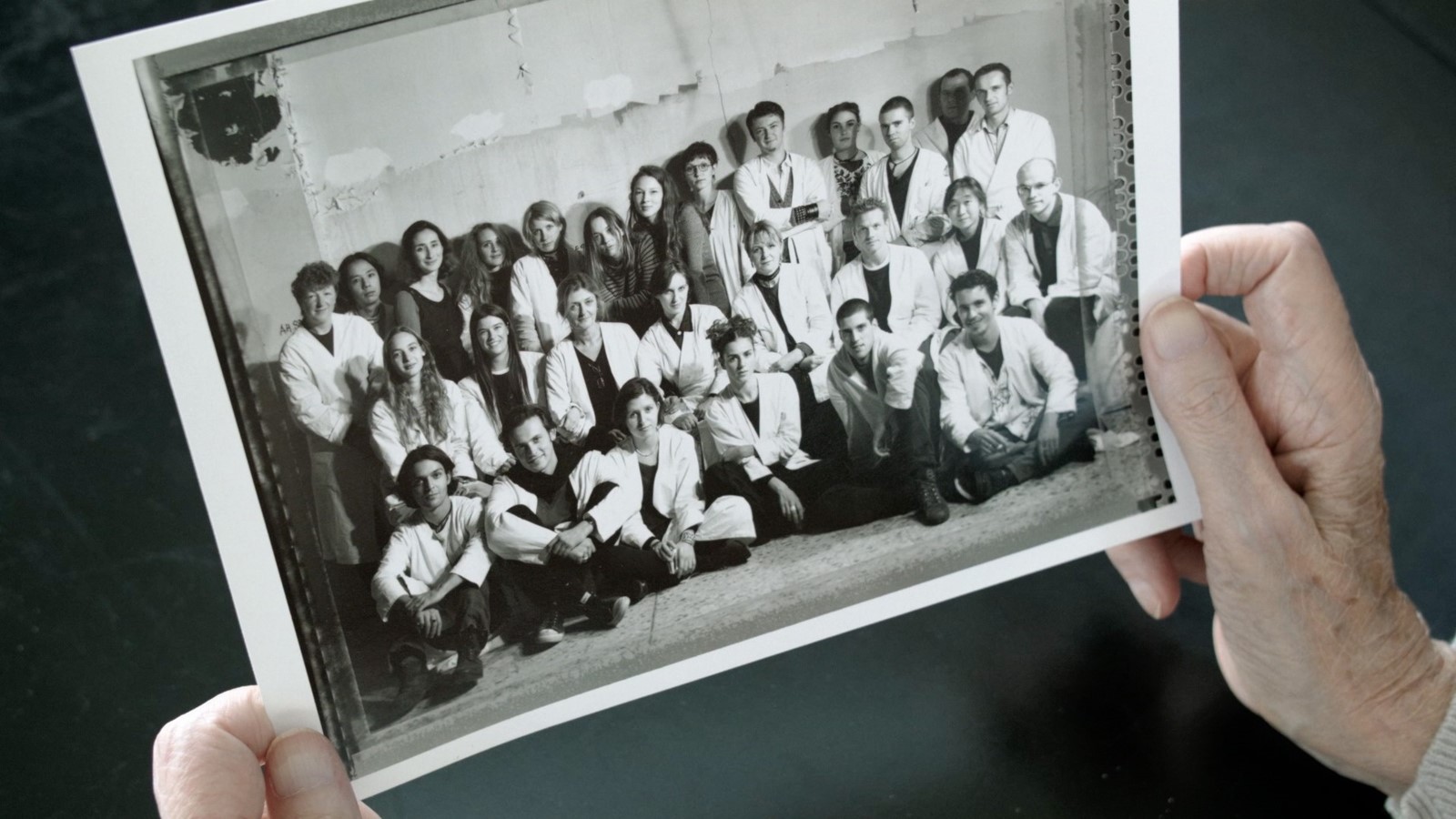

There is a famous image of the team at Maison Martin Margiela that was captured by Annie Leibovitz and published in 2001 in US Vogue. Including everyone from the sales and communication people to the design studio, no more than around 50 people feature, lined up wearing the signature blouses blanches (loosely translated as white coats) that were – and still are – the uniform of the house. The image is most remarkable for the fact that one little white chair in the front row is empty. Located between Jenny Meirens, Martin Margiela’s creative and business partner with whom he founded the business in 1988, and Patrick Scallon, the house’s communications director from 1993 to 2008, it was the place reserved for Margiela himself who failed to appear. Leibovitz has, let’s face it, photographed more wide-angled superstar line-ups than most and was, reportedly, none too pleased about this particular no-show. The end result of Martin Margiela’s absence, though, couldn’t have led to a more masterful encapsulation of the spirit of the place in question and the way in which it functioned.

With that in mind, the “We” in the We Margiela, a much-anticipated documentary on the workings of this fashion institution, directed by Mint Film Office and premiering at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen on Sunday, refers to, as Scallon himself puts it in the film: “everything around the clothes… The ‘We’ existed on one floor of the house that had a creative director on the top floor.” And that creative director was Margiela himself, a designer who eschewed the spotlight as if his very existence depended on it. It is highly unlikely that he would have been afforded the luxury of so-doing today. Neither – and more importantly – would he have been allowed such creative freedom without the ‘We’ part of the equation. Because the ‘We’ allowed Margiela to function in a way that is unprecedented, never being interviewed or photographed, rarely interested in the business side of things and supported by an inner circle of men and women who were as gifted as they were loyal.

“There was a sense of protecting the place we worked, of being discreet, and that made it feel special,” says Harley Hughes, then menswear designer at Margiela, in the film, and that sense is palpable throughout.

However democratic the mindset behind Maison Martin Margiela – and even the name of the house was created to deflect attention from the designer allowing him to maintain his behind-the-scenes position while the business grew – at the centre of the ‘We’ was Meirens. She died in July this year but her presence looms large throughout the film and her words are especially precious in light of that. Scallon attests to the fact that it was Meirens who “built the atmosphere and behaviour around the clothes” although it is testimony to her modesty that she herself never makes such a claim. Meirens does say that her favourite memory was “the start, of course”. And the distinct impression of those early years is of a relationship between a man and a woman whose belief in each other was second to none. “To me, Martin is an artist,” Meirens says. Her voiceover is against a white screen which couldn’t be more apt: the use of white, or in Margiela-speak “whites” was always central to the whole. “He uses fashion as a way to express himself,” Meirens continues, “but he could just as easily be a conceptual artist, a great artist. Martin experienced things in a childlike way. To him, designing is so playful, so light, so… I thought that was exceptional. He would have been big anywhere, but different depending on where it was.”

“To me, Martin is an artist. He uses fashion as a way to express himself, but he could just as easily be a conceptual artist, a great artist” – Jenny Meirens

Praise indeed, and from a woman who was, in her own right, a force to be reckoned with: it was Margiela who asked Meirens to form a partnership with him, her already being a fixture on the Antwerp fashion scene, not least as the first person to bring Comme des Garçons to that city: she opened a store for Rei Kawakubo there in 1984.

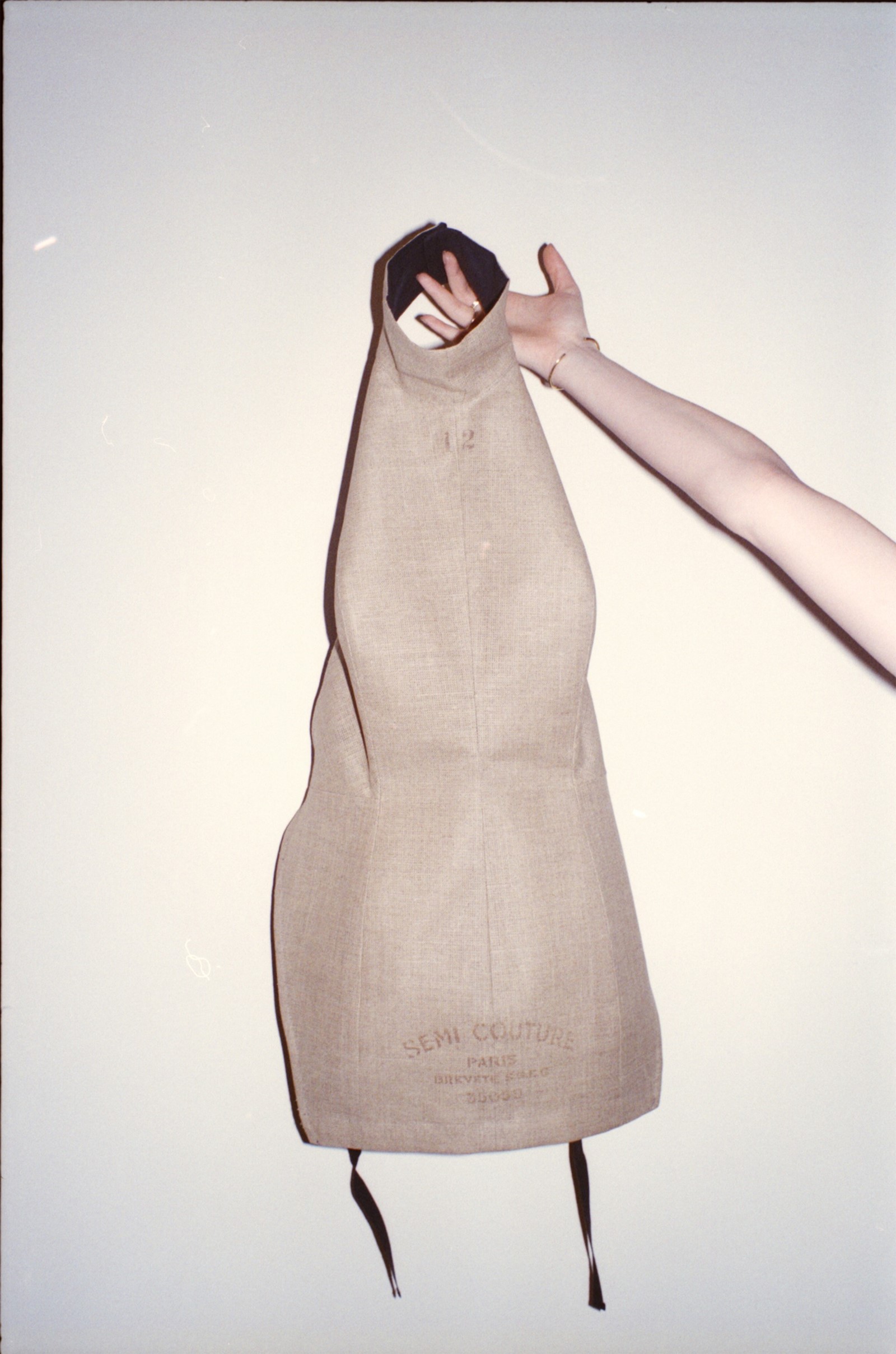

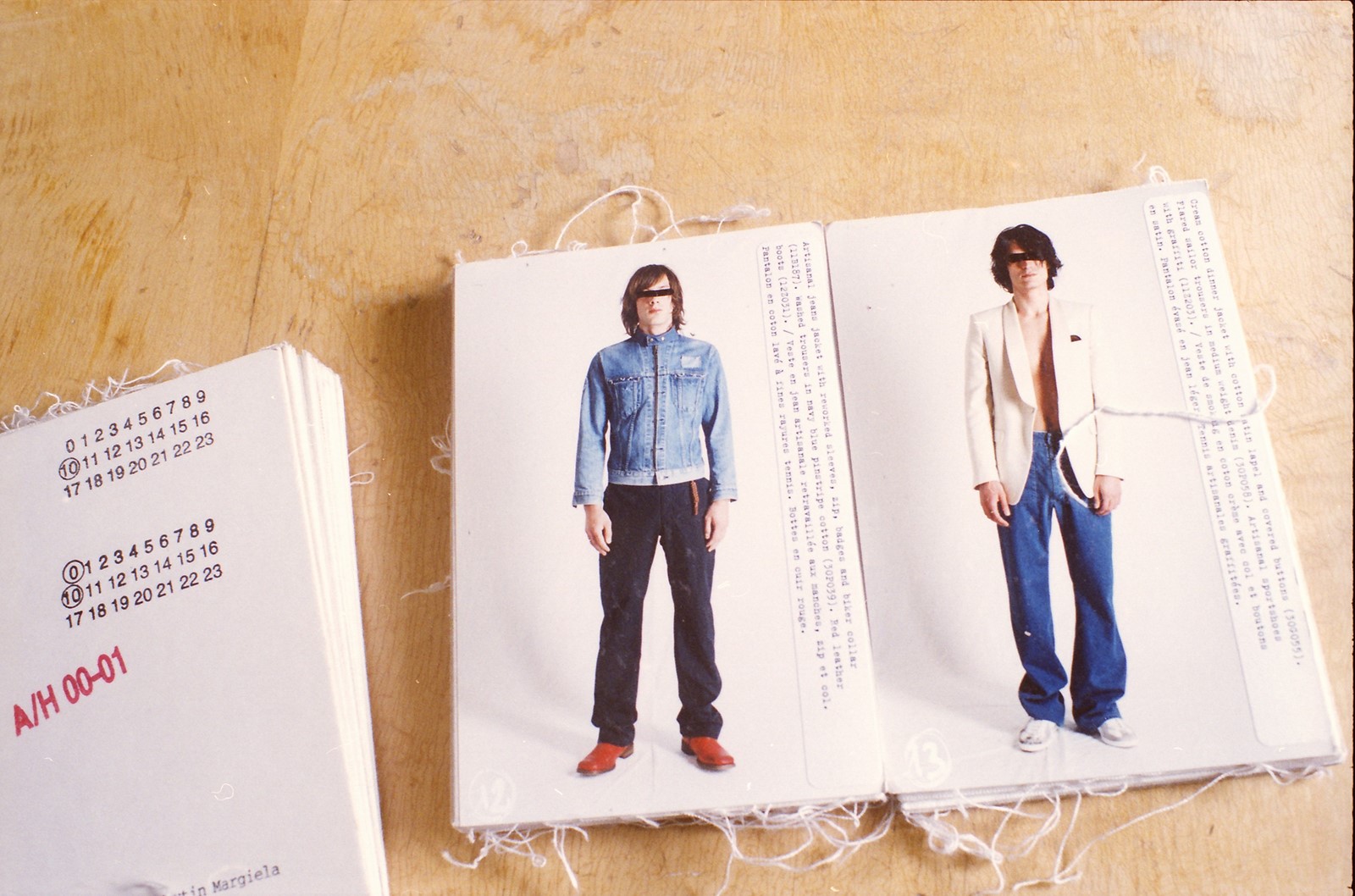

It started out with just the two of them, ideas bouncing between Meirens and Margiela, talking about everything from the clothes to the blank white label distinguishing the clothes. The latter was Meirens’ idea and it remains the most brilliant subversion of the idea of status in designer fashion to this day. The four also-white stitches at each corner, and the fact that they were visible from the outside in unlined garments, came courtesy of Margiela.

Later, the Margiela team was built by Meirens who favoured staffing the maison with those who had previously worked outside of the fashion industry: she once told me she sometimes found those who had travelled a more conventional path “hysterical”. Her daughter, Sophie Pay, appears in the documentary and worked both as a model for Margiela and for the sales team. Lutz Huelle (designer of knitwear and later the Artisanal collection), Axel Keller (commercial director), Inge Grognard (make-up artist) Anders Edström (photographer) all also speak with passion and depth about their time working with the house.

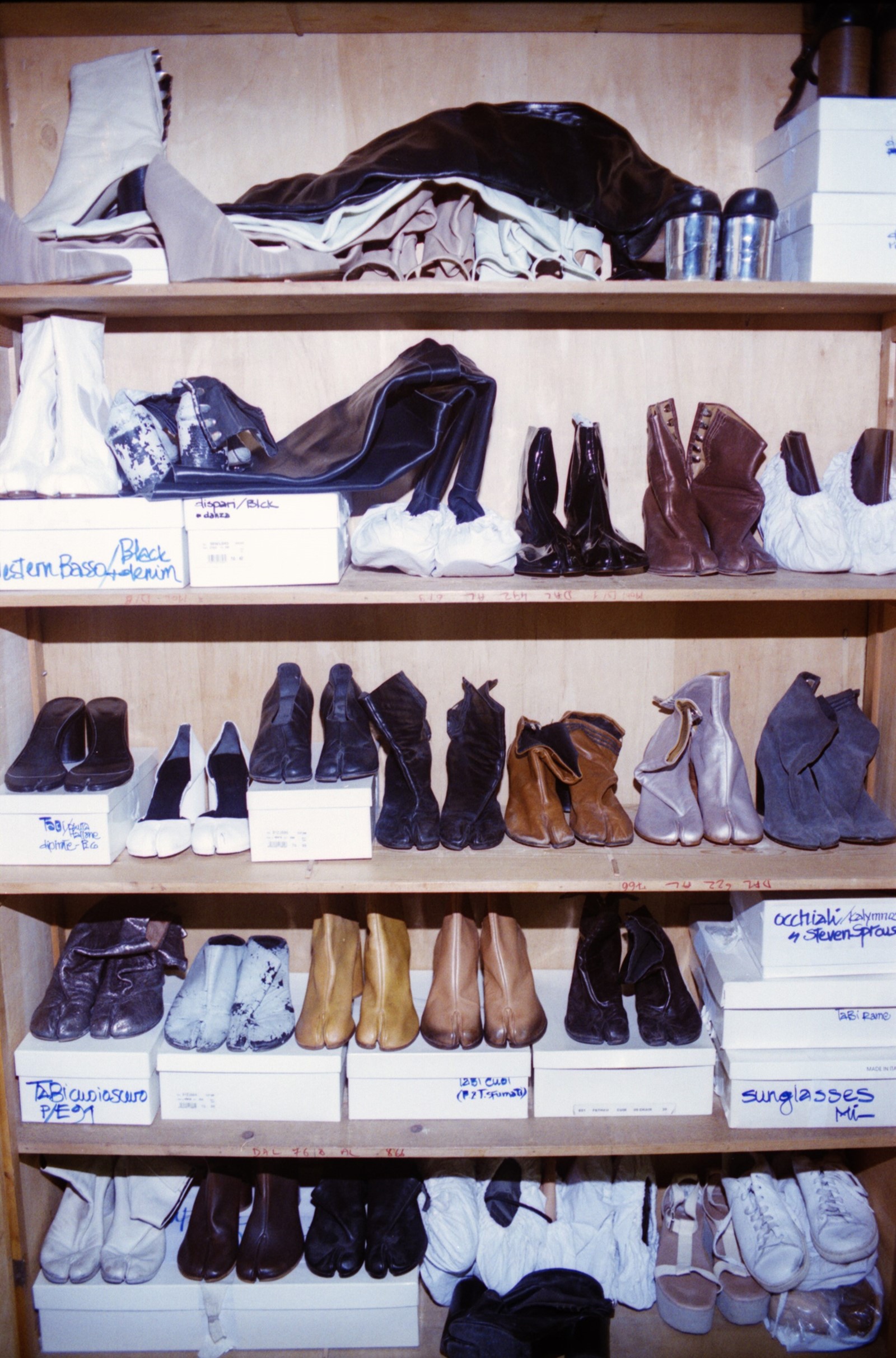

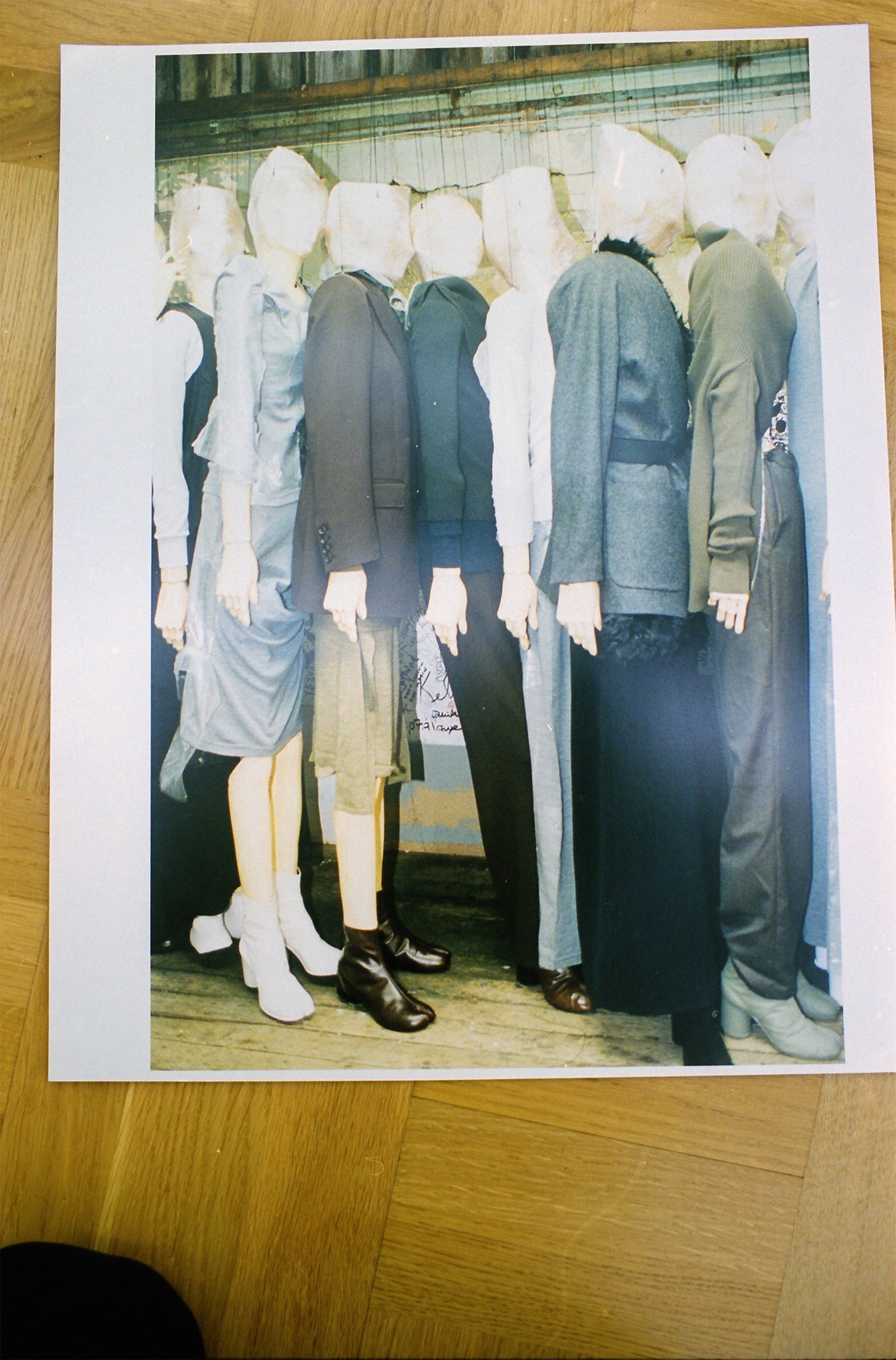

In the background are piles of Tabi boots, the split-toe shoe based on Japanese workwear, that is still a mainstay of the business to this day, Stockman jackets, deconstructed tuxedos… The unusually thoughtful words of all who came together to form this moment in fashion history are also supported by rare film footage of, for example, the way to wear the Martin Margiela duvet coat (it came with its own cover), coverage of the infamous Autumn/Winter 1997 show where the collection was unveiled in three different locations around Paris with models in wigs cut from vintage fur coats were ferried from place to place on a rented bus accompanied by a Belgian brass band, of Grognard swiping dark stripes across models’ faces with a paintbrush shed new light on the power of this entirely distinct vision. The list goes on.

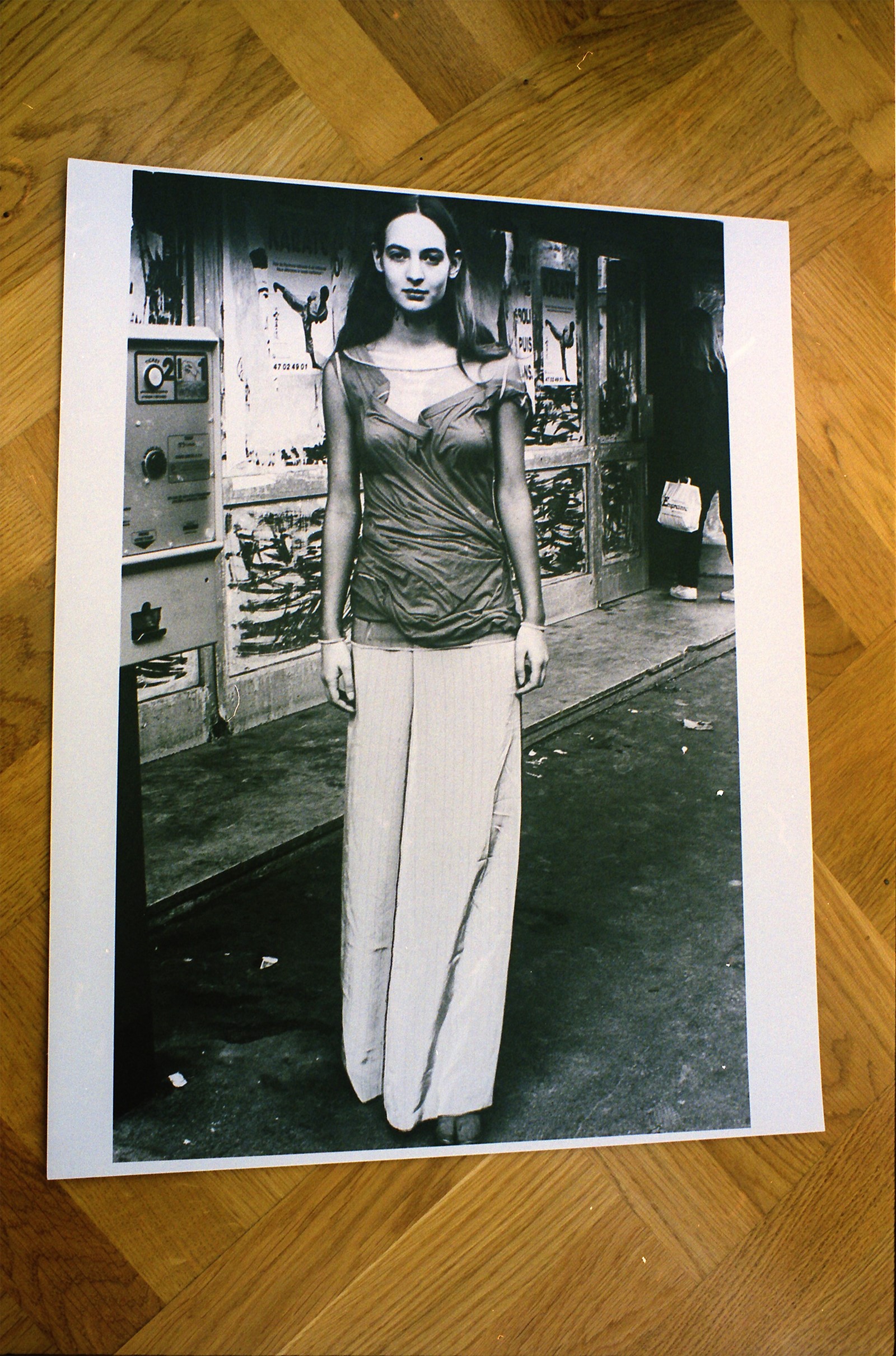

It is not news that Margiela’s archive has been ripe for reinvention for many years, even decades, and that is perhaps partly because of the reticence of both the designer and his team to shout about it. Now, more than ever it resonates everywhere from Vetements and Kanye West’s Yeezy to Raf Simons and Céline. And any influence stretches beyond the clothes: the casting of unprofessional models, the studiously eccentric locations or mise en scènes, the jolie laide hair and make-up and much, much more continue to inform other, often great designers long after Margiela and Meirens stepped down. She retired in 2002 having sold a majority stake in the business to Only The Brave Founder, Renzo Rosso, and Margiela himself followed in 2008.

It is not uncommon a decade later for the world to look at Maison Martin Margiela with rose-tinted glasses but that belies the huge amount of work and difficulty – not least financial difficulty – creating such a proudly unconventional world entailed. It was, then, a labour of love. With that in mind, there is a certain melancholy that the filmmakers should be applauded for not glossing over, particularly as the company expanded and the ties between the team were cut.

“There is a limited amount of time you can exist in a certain way,” Harley Hughes says.

For her part, Meirens, who opens and closes the documentary says: “At the end, I was sick and tired. I was tired. I was 58 years old and I’d just lost my mum. I didn’t have the energy for another ten years. I think he’d lost sight, lost faith. I honestly think Martin didn’t see the results of all those efforts until we sold the company. Only then did he realise what his name was worth.”

As for Martin Margiela, the designer is conspicuous by his absence in the film. And that, perhaps, is just as it should be. We Margiela indeed.

We Margiela will premiere October 22, 2017, at Museum Boijmans van Beuningen and LantarenVenster, Rotterdam.