In a fashion landscape where lightning-quick turnaround – of everything from product to designers’ tenures – has become the order of the day, there’s a seductive power to longevity. Chris Moore, the 83-year-old veteran British photographer, has been photographing the international catwalks longer than anybody else. He’s also outlasted most designers, bar Karl Lagerfeld (he joined Fendi two years before Moore began shooting the catwalks). 2017 marks his 50th year in the taffeta-lined trenches of the fashion shows which, in 1967, were still biannual affairs whose primary sphere of focus was Paris, for the haute couture.

Moore has seen not only several thousand fashion shows, but the entire birth of an industry – that of ready-to-wear, and the runway shows to accompany it. When Moore began, catwalk shows did not exist: fashions were quietly presented in salons, closed to prying eyes, with photography banned. In Moore’s first season, he photographed outfits chosen by the houses – if they would permit photographs at all (major names, including Balenciaga, would not). The models posed on the streets, or in the lobbies of adjacent hotels, and Moore paid each a fee for their time. Designer ready-to-wear had only been established a year prior, by Yves Saint Laurent and his Rive Gauche. It was phenomenally commercially successful in the outset – but no-one realised that this lucrative offshoot would prove the creative future of the fashion industry.

Chris Moore’s unique training made him a prime candidate to record this seismic fashion shift. He’d already trained at Vogue Studios in London, joining in 1954 and assisting some of the era’s great fashion photographers, including Henry Clarke and Cecil Beaton, on editorial shoots. Prior to this, Moore cut his teeth as a commercial photographer on Fleet Street. That fusion, of high fashion and rapid-fire photo-journalism, was the perfect combination for an age about to emerge – of the “catwalk show” true.

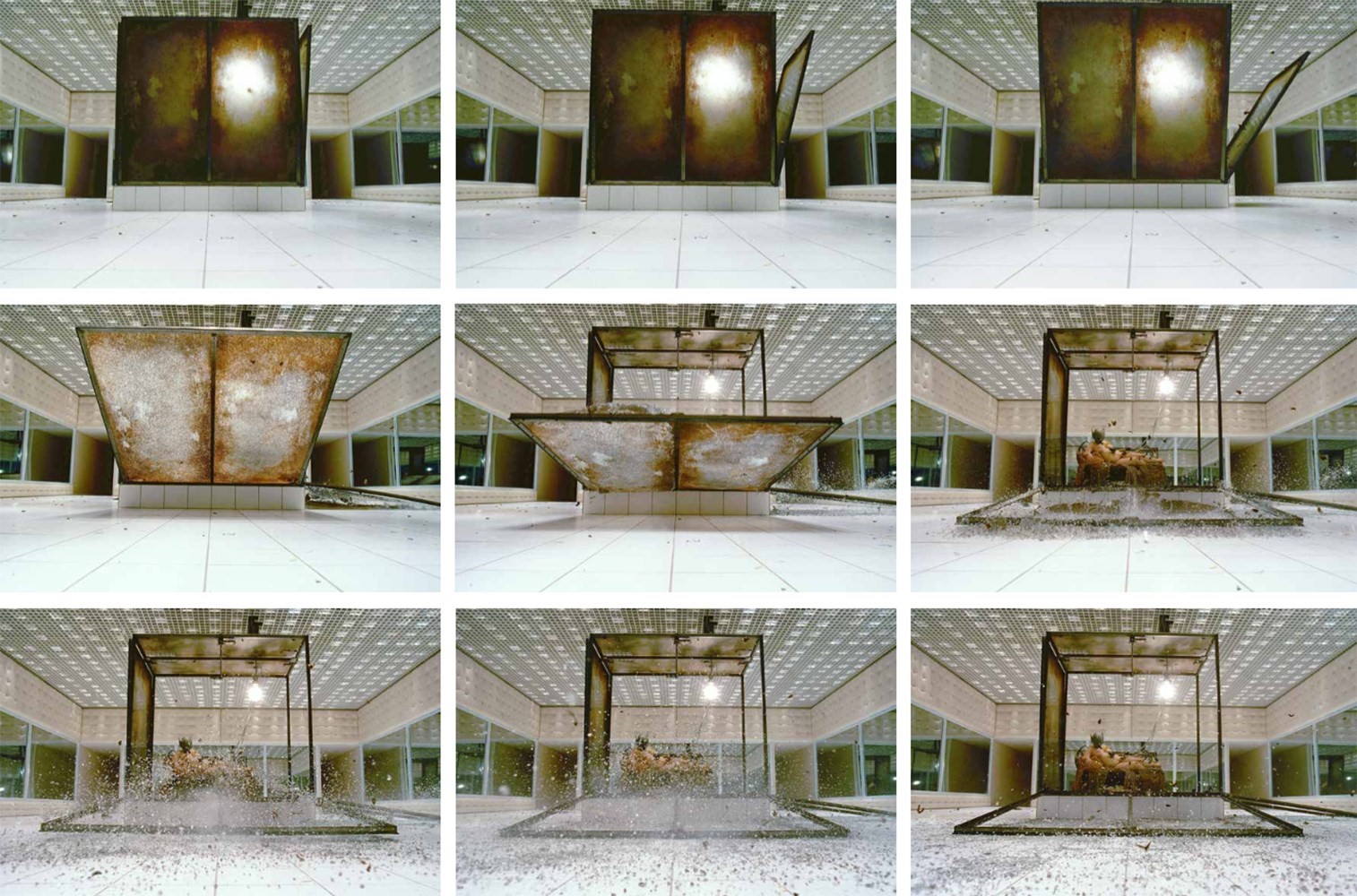

Moore’s style is extraordinary because it combines the refined eye of a fashion photographer with the opportunism of a photo-journalist – capturing specific moments, but with an aesthetic consideration hitherto missing. That became all-important as designers began to transform the fashion show into major visual events – both haute couture designers like Saint Laurent, and the burgeoning ranks of what the French dubbed ‘créateurs’, like Karl Lagerfeld at Chloé and Kenzo Takada, whose fashion shows featured models dancing, laughing and careening around increasing raised catwalks – stages, for spectacles, taken to new levels in the 1980s and 1990s by the likes of Mugler, Gaultier, Galliano and McQueen. Moore charted them all – indeed, few in fashion can boast to have seen more than Moore.

Rifling through his archives – held digitally since 1995 but, more fascinatingly, as millions of slides and contact sheets, painstakingly catalogued in thousands of cardboard boxes, charting the previous three decades – the moments that struck me were the unfamiliar, the unseen. A shot of Pierre Bergé, the late CEO of Yves Saint Laurent haute couture, glimpsed in the reflection of a mirror at a 1975 show; a young Grace Coddington captured in the middle of the front row at a late-70s Pierre Balmain presentation; Marc Jacobs models blurred with confetti; Saint Laurent himself passing the front row in his salon, spectators captured in silent screams of approval. Alongside every famous shot was a multitude of alternative angles, different views, harking back to the time when, for many long-distance fashion enthusiasts (including myself), Moore’s images in magazines and newspapers – most notably the International Herald Tribune, where he worked with Suzy Menkes for over 25 years – were the definitive viewpoint on some of the greatest shows on earth. They are now collected in Catwalking: Photographs by Chris Moore, whittled from over ten million (at a conservative estimate) to around 400.

The book itself is a mix – of famous images, and unfamiliar points of view. What it isn’t is a comprehensive chart of 50 years of fashion’s evolution – it centres around the theatre of the catwalk show, championing those designers who performed best under its proscenium arch, on its raised stage. John Galliano, for instance, is amply represented under his own name, and at Givenchy, Dior and Maison Margiela (he also wrote the book’s foreword). What it also shows, I feel, is the personality of the photographer himself: how Moore’s eye roamed during shows that were, perhaps, lacklustre, to find points of view that were interesting for posterity. Balmain, for instance, wasn’t exactly in its heyday in 1977 when Moore chose to focus on Coddington in the audience, leaving the clothes a blur of satin and tweed. At the time, a fashion editor would have raged. In retrospect, it’s far more interesting that way.

There is also an idea of the difficulties – shots framed by other photographers, jostling for position; an image of Yves Saint Laurent and Catherine Deneuve embracing which, Moore recalls, was only achieved by him sweeping jewellery off a table and leaping onto it as a makeshift podium. Other shots, in the 70s, were taken with Moore perched on fireplaces and windowsills. In the late 1970s Moore met the war photographer Don McCullin, photographing for the London Sunday Times. He remembers McCullin remarking to him “Do you know, it’s easier to be a war photographer than it is to do this job?”

Moore smiled wryly as he recalled this. It’s no easier these days – he recalls being turfed out of shows by obsequious PRs in the 1980s (“they thought we were spying!”) – and allows that certain shows are still difficult to infiltrate, even legitimately. And yet he still shows no sign of retiring. “It gets in your blood,” he once told me, as this book was being pulled together. “Fashion is fascinating.”

And, to borrow the words of John Galliano, “Chris Moore is the eye that shows it to the world.”

Catwalking: Photographs by Chris Moore, with foreword by John Galliano, is out now, published by Laurence King.