Many designers indicate their wish to craft a universe, but few achieve it as truly as Pierre Cardin, the now-nonagenarian pillar of Parisian fashion. Cardin is better known as a name than as a man, and a name largely divorced of links to specific fashion movements, silhouettes or garments. Although he built his reputation in the 1960s pioneering avant-garde styles that cemented the sci-fi look of the Space Race era, the words “Pierre Cardin” are almost an abstract now, known to much of the world not from the labels of clothing, but the packaging and sloganeering of a wild litany of products best grouped under ‘miscellaneous’.

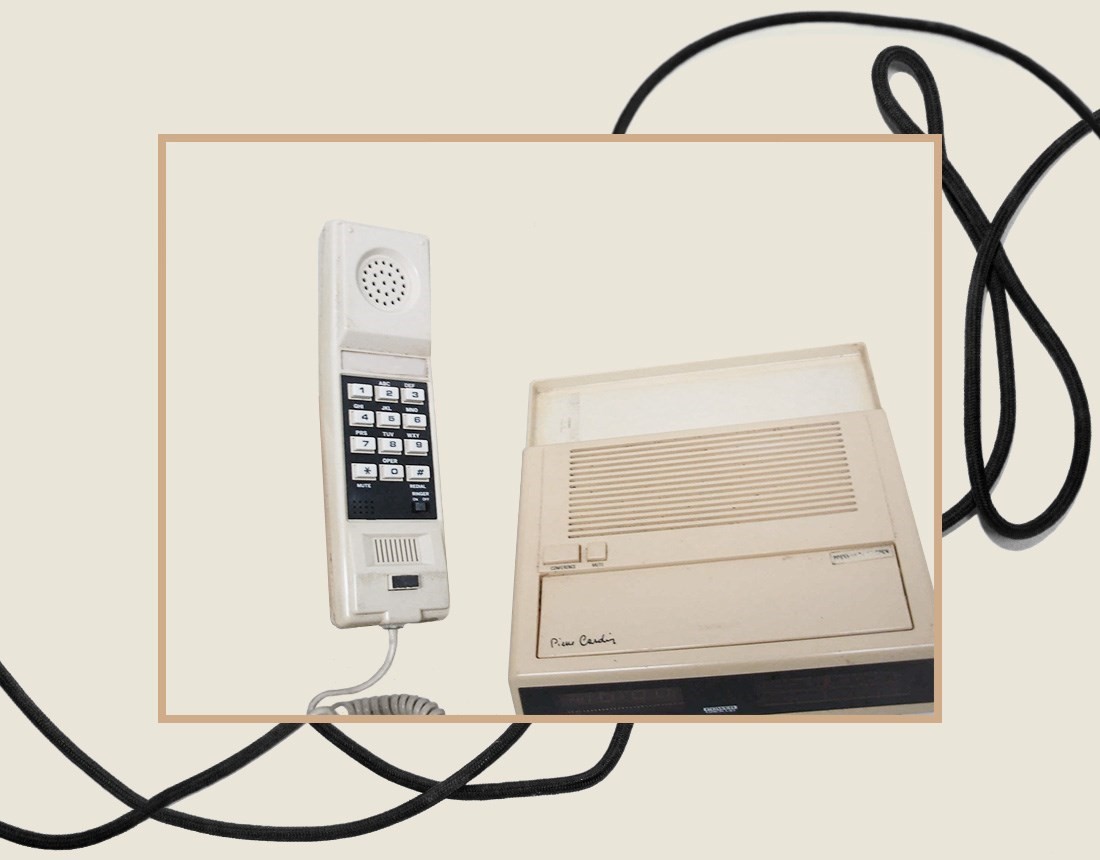

A surface dredge of eBay reveals treasures from the very depths of Pierre Cardin’s licensing mania: cup-warmers, answering machines, miniature golf sets, christmas towels, tupperware, even electric food-mixers. Most famously, Cardin produced a licensed line of tinned sardines. “During the war, I would have rather smelled the scent of sardines than of perfume,” Cardin stated, by way of defence. Divorced from context – namely, from when Cardin was still a major player in the couture calendar – these forays into brand mismanagement are mildly hilarious.

Cardin began his career conventionally enough, in the storied salons of French haute couture. His first employers were the houses of Paquin and Schiaparelli in 1945, who engaged and trained the young Cardin in tailoring. The following December he moved to the new house of Christian Dior; his was the hand that cut the very first ‘Bar’ jacket for Dior’s debut Spring 1947 collection. Three years later, he established his own maison de couture – partly in a fit of pique at being questioned by police following the leaking of Dior’s new season designs to copyists.

It would be convenient to trace Cardin’s democratisation of fashion first, and the abstraction of the designer name second, to this run-in with the law over the prissy protectiveness of post-war haute couture. But he wasn’t the first to license his name: Couturiers had created perfume lines for decades, and his erstwhile employer Dior cemented its name in the popular consciousness with a bunch of products tenuously linked to the world of French fashion. Dior gained worldwide fame through the ‘New Look’, but it made its fortune through licensing that fame to hosiery, scarves, men’s neckties and the like. Cardin went further, establishing a whole range of ready-to-wear bearing his brand (if not his design signature) in 1959. It was so controversial a move that he left the Chambre Syndicale de la Haute Couture Parisienne, the governing body of French couture, in part over the controversy this caused. (He was back in the fold within a year.)

By 1968, though, the ever-rebellious Cardin decided to apply his moniker to his first license contract outside of fashion – he created a line of Modernist pottery. During the 1970s, when designer ready-to-wear exploded and the demand for goods bearing a fashionable name became too lucrative to ignore, Cardin signed multiple contracts. By 1985, he boasted 840 licences, and was indirectly responsible for 160,000 employees in 580 factories around the world. In 1981, he bought the French restaurant Maxim’s, creating another branding empire – bizarrely, the Maxim’s name appears on a line of menswear and fragrances, just as Cardin’s appeared on foodstuffs. It also appeared on lots of cheques: Cardin’s empire became vast, and the man vastly wealthy. He bought the rotund retreat Le Palais Bulles (the bubble palace) in 1991; today, his fortune is estimated at around 400 million Euros, but no-one knows for sure as the company is privately held. “It’s much more than people say and much less than they think,” states Cardin, enigmatically, of that empire.

Today, Pierre Cardin’s aggressive licensing is, simultaneously, out of fashion and back in style. Luxury houses have reversed the trend of allowing their names to be slapped across all manner of esoteric products of questionable quality: to many, Cardin’s nose-dive from one of the most esteemed labels in fashion to a bargain-bin cast-off serves as a cautionary tale. At the same time, a new generation of designers are ironically reclaiming Cardin’s breed of dodgy slogan-stamped wares. Demna Gvasalia’s Balenciaga has revived blatant logo patterns and the double-B Balenciaga emblem used heavily on small-leather goods of dubious quality in the 1980s; the brand has even titled a new line of jewellery ‘License’, underlining the naff notion of Duty-Free Glamour that inspired Gvasalia’s designs. They intentionally question luxury and taste, in on a joke that perhaps Cardin never got. Ultimately, though, only time will tell if Cardin’s lasting legacy will be his name on Space Race haute couture labels, or slapped on the side of sardine tins.

Pierre Cardin by Jean-Pascal Hesse is out now, published by Assouline.