On the anniversary of Piet Mondrian’s death, we look back to the 1965 YSL collection which took the artist’s geometric abstractions and put them on a dress

Few designers can claim such a profound influence on the way women dress as Yves Saint Laurent. The pieces he pioneered – the man’s tuxedo, cut for a woman’s body, the safari jacket, the trench coat – are now so congruous with women’s wardrobes that they seem like they have been there forever.

But beyond these pieces, the ones so often linked to Saint Laurent’s name, it is worth remembering that the designer worked under his eponymous label for over four decades, with collections that ricocheted between cool, androgynous tailoring and the all-out opulence of 1980s Parisian haute couture, creating thousands of runway looks in the process. The stand-out collections number too many to list, stretching from the haute baboushkas of his Russian-inspired ‘folk-luxe’ Ballets Russes collection, to his notorious evocation of 1940s excess for Spring 1971. (So controversial was that one, harking back, as many in the fashion establishment saw it, to Nazi-occupied Paris, that one critic deemed it “suicidal”.)

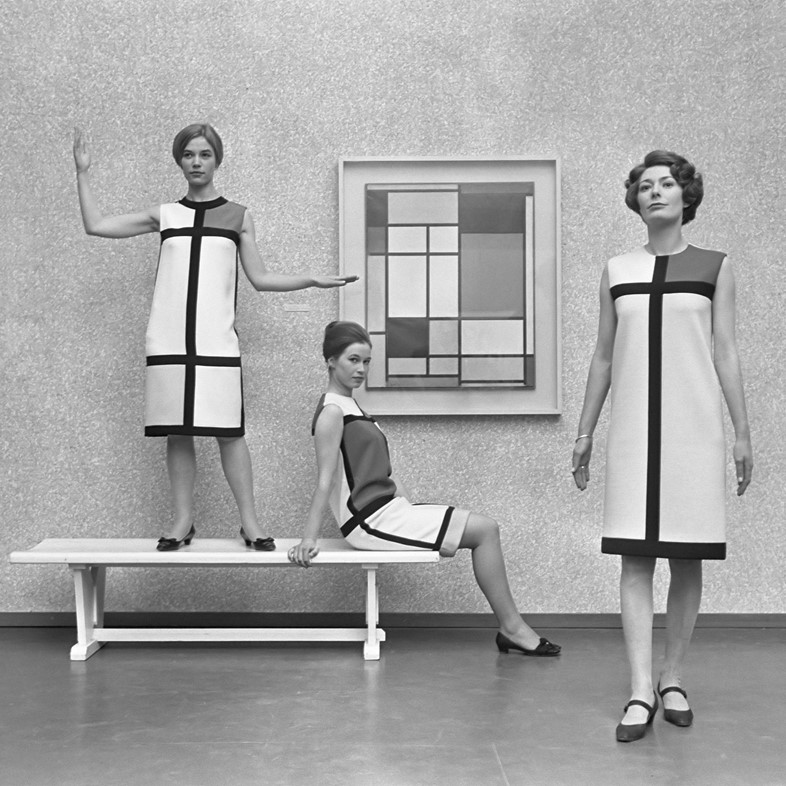

That said, few of Saint Laurent’s shows lodge in the collective memory quite like his Autumn 1965 Couture collection, now simply known as ‘The Mondrian Collection’ for its evocation of the Dutch De Stijl artist’s colourful geometric abstractions. It’s partly a misnomer – only six of the gowns actually contained reference to Mondrian’s work, in a collection of over 80 looks. But the name is a testament to their cultural power – the beginning of a lifelong dialogue between fashion and art that would define Saint Laurent’s career.

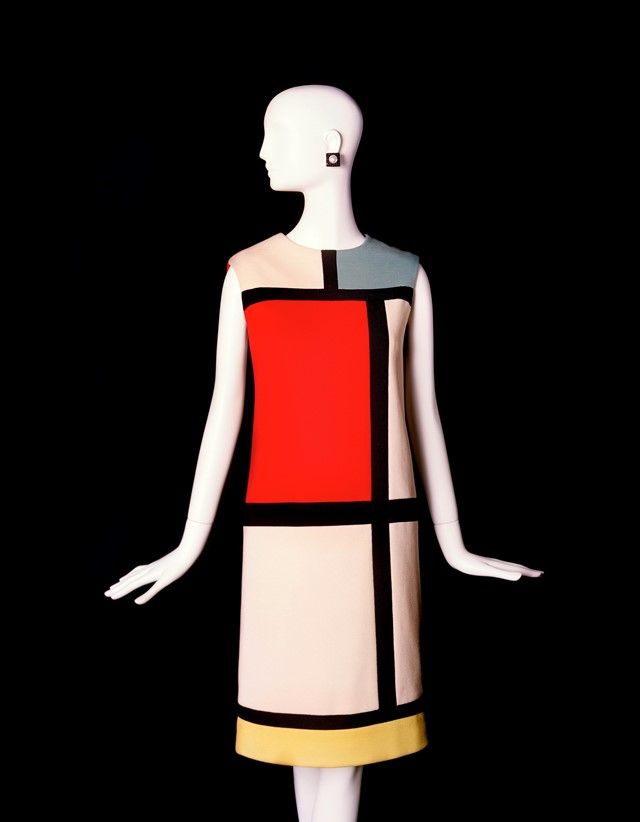

On first look, the dresses have the deception of simplicity – cut in the popular ‘shift’ style of the day, their A-line shape, in wool jersey, allows an ideal field for Mondrian’s blocks of colour. But, like the artist’s paintings – in which the intricate brushstrokes are only revealed when you are close enough to see them catch the light – look closely at its construction and Saint Laurent’s gown is actually a feat of dressmaking, each block set with invisible seams to hold the A-shaped line.

The Show

The Autumn 1965 Couture show came at a time when Yves Saint Laurent was, ostensibly at least, struggling to keep up with the modernity of his contemporaries, particularly the Space Age designs of André Courrèges, whose evocative 1964 collection ushered in the intergalactic look of clean, manmade fabrics and high hemlines – the first iteration of the mini skirt in haute couture, made for the modern woman who needed to move.

Saint Laurent was well aware of the need to break new ground. “I have changed my whole concept – everything is new – this collection is young, young, young,” he said on the day of the show, following on from a collection earlier that year that had received little critical acclaim for its well-trodden ground of tailored tweed and patterned silks. Later, he would elaborate. “Mondrian was my last minute inspiration,” he told France Dimanche. “Nothing was alive, nothing was modern in my mind except an evening gown I had embroidered with paillettes like a Poliakoff painting. It wasn’t until I opened a Mondrian book my mother had given me for Christmas that I hit on the key idea.”

The show itself was an ode to art generally – touching not just on the work of Mondrian and Serge Poliakoff, but also Russian Formalist Kazimir Malevich. That said, it was the Mondrian gowns that demanded the attention of the gathered. Styled simply, they were worn with a pair of single-buckled pilgrim shoes by Saint Laurent’s longtime accessories collaborator, Roger Vivier. Those shoes ended up being part way as enduring as the clothes themselves – largely thanks to Catherine Deneuve, whose character in the seminal French film, Belle du Jour, famously wore them with a patent trench coat.

The People

Of the collection’s many fans was legendary American Vogue editor Diana Vreeland, who gleefully declared in the New York Times that this was, simply, “the best collection”. The other publications of the day agreed – WWD declared him to be the “king of Paris”, whilst Harper’s Bazaar said of the Mondrian dress itself: “this is the dress of tomorrow – the assertive abstraction, a semaphore flag, perfectly proportioned to flatter your figure”.

The dress was so popular that it found itself worn by several notable women of the day, but is perhaps epitomised best by the image of bug-eyed English model Moyra Swan on the September 1965 cover of Vogue Paris. There, like an advertisement for the Swinging Sixties, she is slanted across the cover with a Vidal Sassoon-style bob, wearing the Mondrian shift with its matching Roger Vivier shoes.

Over the next year, Mondrian dresses, or their imitators (including British designer Mary Quant’s Mondrian go-go boots) flooded the fashion world. Such was their ubiquity that poster girl of the age Jean Shrimpton (herself shot in the dress for the September 1965 edition of Harper’s Bazaar by Richard Avedon) would declare the design, by the end of that year, “boringly popular”.

The Influence

It barely needs saying that since Saint Laurent, many a designer has dabbled in the world of high art. One such notable collection is Versace Spring 1991, for which Gianni Versace emblazoned gowns and bodysuits with the Pop Art images of Andy Warhol, a man who the designer claimed as a soulmate for his collective obsession with material culture. The house of Louis Vuitton has long thrived on artistic collaboration; their signature Damier check luggage has been given new life over the years by various artists, from the neon graffiti scrawls of Stephen Sprouse to the spots of Yayoi Kusuma. Art and fashion have criss-crossed too many times to list.

But the collection’s influence goes beyond its appropriation of art – more potently, it marked the birth of ready-to-wear as we now know it. Such was the dress’ popularity that Saint Laurent became the first designer to create a pattern of a couture gown, available for sale to the world through Vogue Patterns and the reason why so many Mondrian dresses now exist, made not in Saint Laurent’s Parisian atelier but in women’s homes, from the fabric they had available to them. It’s why on some you will find the colours flipped or the pattern reversed, on others, blocks not of colour, but florals or stripes. It was perhaps the first time that a singular garment had so explicitly influenced what women wanted to wear.

A year later, as a response of sorts, Saint Laurent opened Yves Saint Laurent Rive Gauche on Paris’ Left Bank, housing his own ready-to-wear line. If people were to make money from non-couture versions, why shouldn’t the original designer? It was the first time that a couturier had opened a ready-to-wear line in Paris – and remains the groundwork for how fashion operates now.

All of which amounts to why, though Saint Laurent’s legacy remains tied to the elegant lines of Le Smoking, it is this collection that remains such a defining statement – a statement that a dress could be injected with intellectual capital, that it could be discussed like art, and that a single gown could excite a desire that radiated far beyond the walls of the gilded salons of Paris, and out into the world.