On the release of a new film on British couture in the 1950s, Phantom Thread, we trace the couturiers who inspired Daniel Day-Lewis’ lead role

In preparation for his latest role, Daniel Day-Lewis learned to sew. He spent a year doing so, absorbing himself in the traditional art of dressmaking under the tutelage of the New York City Ballet’s costume designer, Marc Happel, in a process that was slow, and painful. The year culminated with him recreating a gown by master couturier Cristóbal Balenciaga, made entirely by hand. Only when the dress was finished, a sheath style in grey flannel wool and lined with lilac silk, could the actor – a man well known for an obsessive dedication to his craft – begin filming.

The role in question was that of Reynolds Woodcock, the fastidious British couturier at the centre of Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest film, Phantom Thread. Creating ball gowns for princesses and society ladies, and stitching secret messages into their seams, Woodcock is a practitioner of a dying art – the film, which is set in the 1950s, picks apart the charged relationship between the designer and his muse Alma, a woman he discovers in a Cotswolds café, as she disrupts his ordered world.

Woodcock, and his atelier the House of Woodcock, are fictional. Anderson has been coy about revealing any exact references to the designers of the age that might amalgamate in his character – but if you look closely enough, there are clues to be found. The eagle-eyed will notice that Woodcock’s tendency to drape his garments evokes the unique style of Balenciaga himself, whose skill at cutting and sewing led to complex new forms that ushered in a new era of excess – and whose legacy can still be felt to this day. He, like Woodcock, was notoriously single-minded.

So too was Charles James, the Anglo-American designer who is remembered for bringing couture to the United States – a man with an uncompromising belief in his own ability that toxically seeped into the way he treated those around him. His gowns were, as Salvador Dalí deemed them, “soft sculpture,” visceral and poetic, but his temperament was perhaps too much for the age in which he lived and worked. “Charlie’s got every talent,” said American Vogue editor Diana Vreeland. “The only talent he lacks is getting on with people. He thinks it’s rather cute.”

That said, Phantom Thread is, at heart, about Britain and its idiosyncrasies, depicting a time in the country’s history when polite, ordered exteriors masked desires that lurk beneath, and social standing was a complex web to be manoeuvred. It is why, though the world of British couture is little known in comparison to its Parisian counterpart, it is no less fascinating – both Anderson and Day-Lewis admitting they became obsessed with this intimate but regimented world. Here are three British couturiers whose influence can be felt in the film – and its costumes.

Hardy Amies

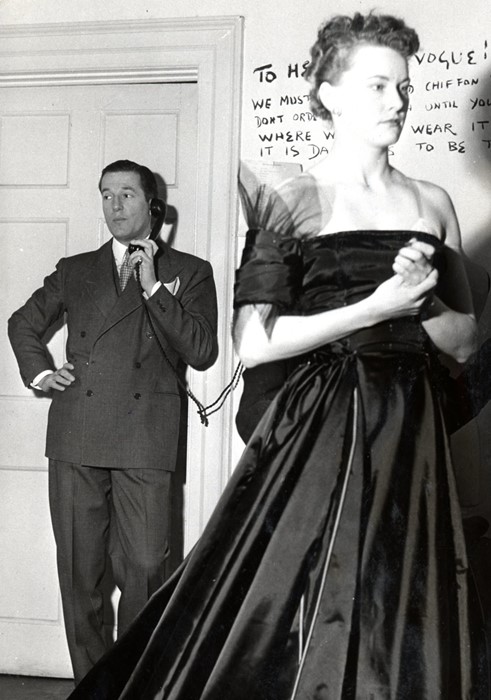

A self-proclaimed snob – “it doesn’t mean to say that you’re unkind to the lower orders, being a snob simply means that I think the top is the best,” he explained – couturier Hardy Amies rose from a modest background to go on to outfit Queen Elizabeth II for almost four decades. Operating from number 14 Savile Row, he is best remembered for his tailoring – undeniably conservative, it was nonetheless instilled with a fluidity that made it popular with society women of London, working under the rule that “day clothes must look equally as good at Salisbury station and the Ritz bar”. Though his outfits for the queen were occasionally deemed frumpy and he was, particularly in the latter half of his career, prone to outspoken attacks on the British designers that followed (“neither I nor my staff would know how to make such clothes, and we would not want to,” he said of John Galliano and Alexander McQueen in The Spectator) he will nonetheless be remembered for the golden age of his career – the 1950s, where his elegantly-cut suiting and constricted waistlines saw him working in the manner of his Parisian contemporaries, Christian Dior and Hubert de Givenchy. In the film, the scene in which Woodcock takes part in a photo shoot with Alma bears striking resemblance to photographs of Hardy Amies and model Fiona Campbell-Walter, taken in 1953.

Norman Hartnell

While Hardy Amies was known for his tailoring, fellow couturier to the royal family Norman Hartnell is remembered for his gowns. So much so that the pale green crinoline evening dress, completely embroidered with sequins, pearls and crystals, made for the queen for a dinner in Washington with President Eisenhower, is known as “the gown that the queen conquered America in”. Even more historically, Hartnell was responsible for the queen’s wedding and coronation gowns. His was a rags-to-riches tale – born in Streatham to a wine merchant, he worked by a clear maxim (“I despise simplicity,” he said. “It is the negation of all that is beautiful”) and employed his famed team of hand embroiderers to realise his sumptuous creations. Hartnell was also a favourite of Princess Margaret – his designs for her provided the inspiration point for Christopher Kane’s breakthrough S/S11 collection, where the designer took Hartnell’s prim lace suiting and re-rendered it in cut-out fluoro pleather. Reynolds Woodcock too has a royal connection, making a gown for an unnamed Belgian princess – the edict for that dress being that it should be made with the fewest amount of seams, the timeless mark of a great couturier.

Edward Molyneaux

Perhaps lesser known is Edward Molyneaux, a one-time sketch artist for London magazine Smart Set, whose drawings of women attracted the attention of one Lady Duff-Gordon, the famed couturier and society woman who worked under the name Lucile (and later fell from grace after reportedly bribing lifeboat members to get in the first boat when she was amongst Titanic’s survivors). His style was more simple than that of his contemporaries, favouring a subdued design with little in the way of superfluous embellishment (“never too rich or too thin,” he said of his designs) leading him to be known as “the designer to whom a fashionable woman would turn if she wanted to be absolutely ‘right’ without being utterly predictable in the 1920s and 1930s”. His work, which echoed the clean-lined modern architecture of the period, went on to influence on the man who would become the most famous of his charges, Pierre Balmain, who described Molyneaux’s studio as the “temple of subdued elegance… where the world’s well-dressed women wore the inimitable two-pieces and tailored suits with pleated skirts, bearing the label of Molyneux”.

Phantom Thread is released in cinemas nationwide today.