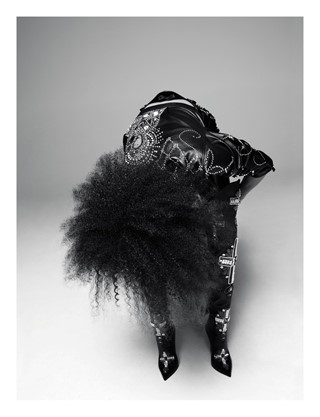

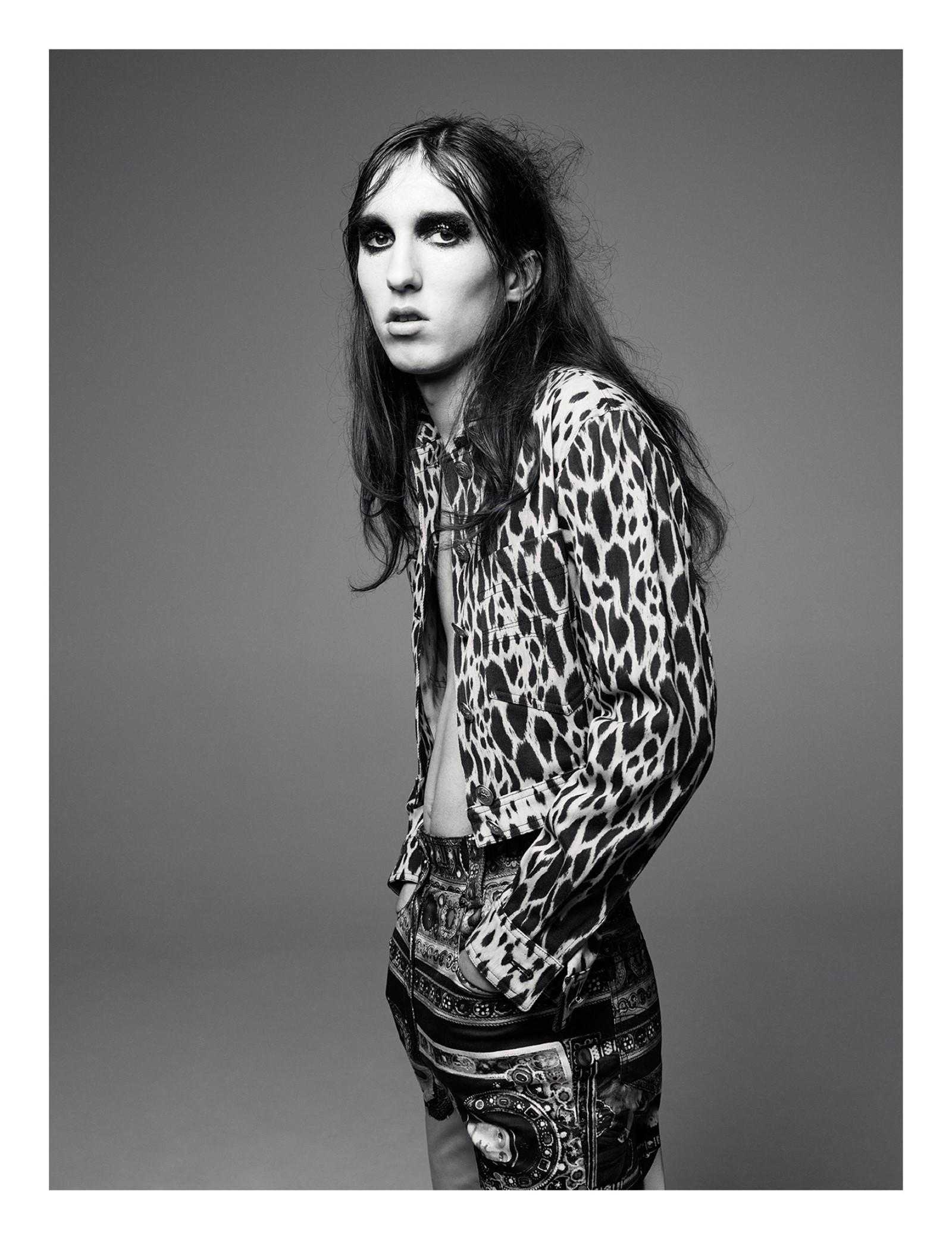

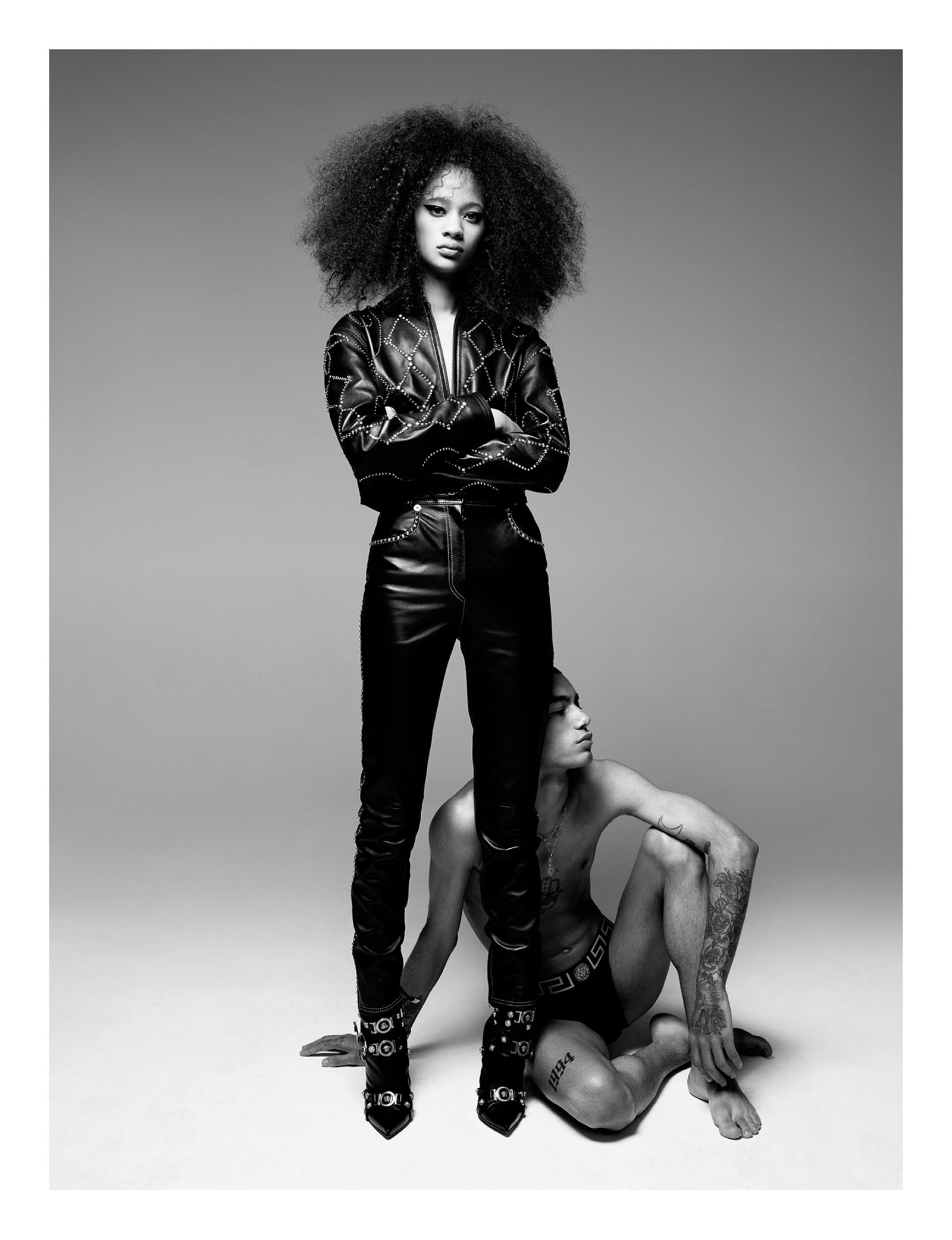

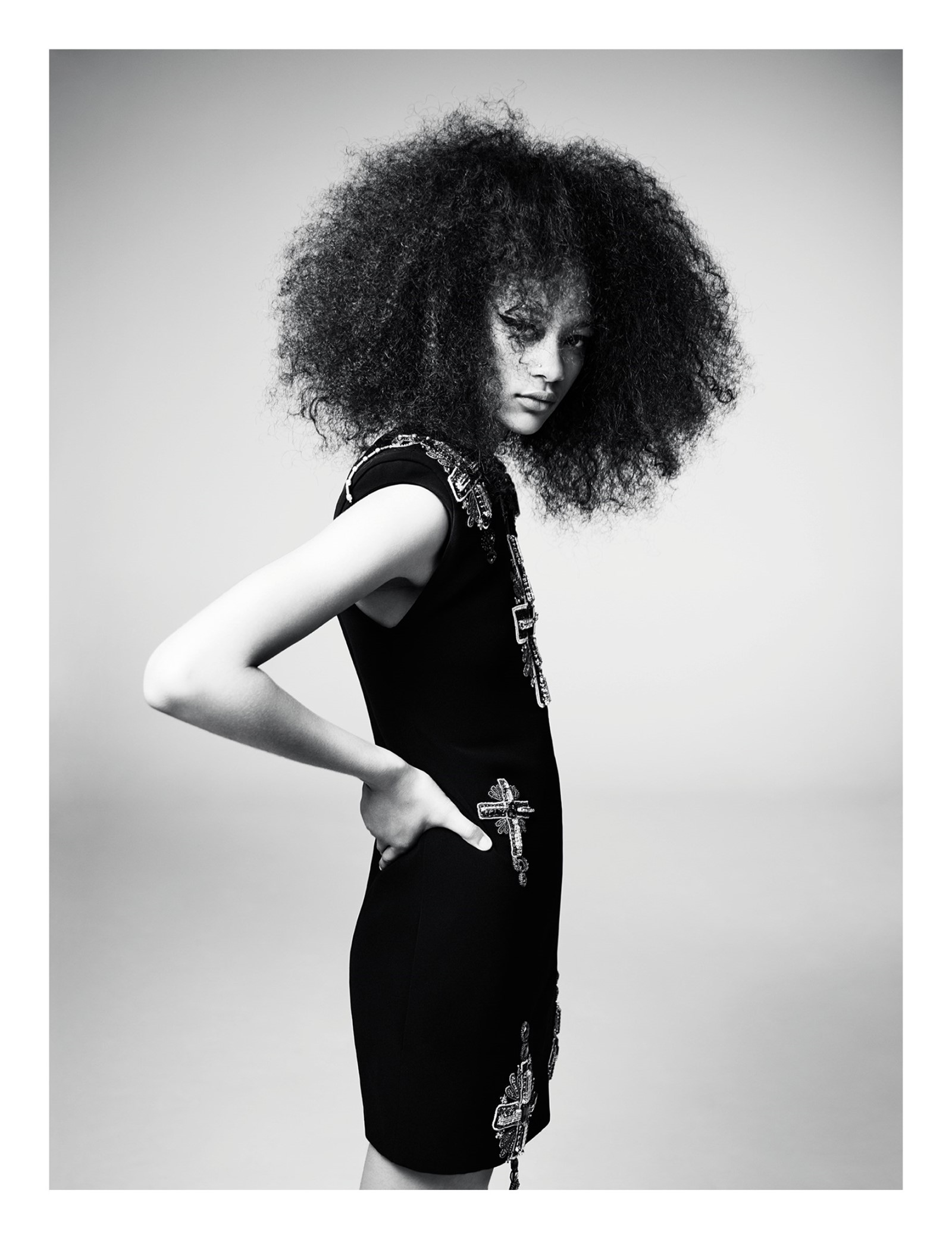

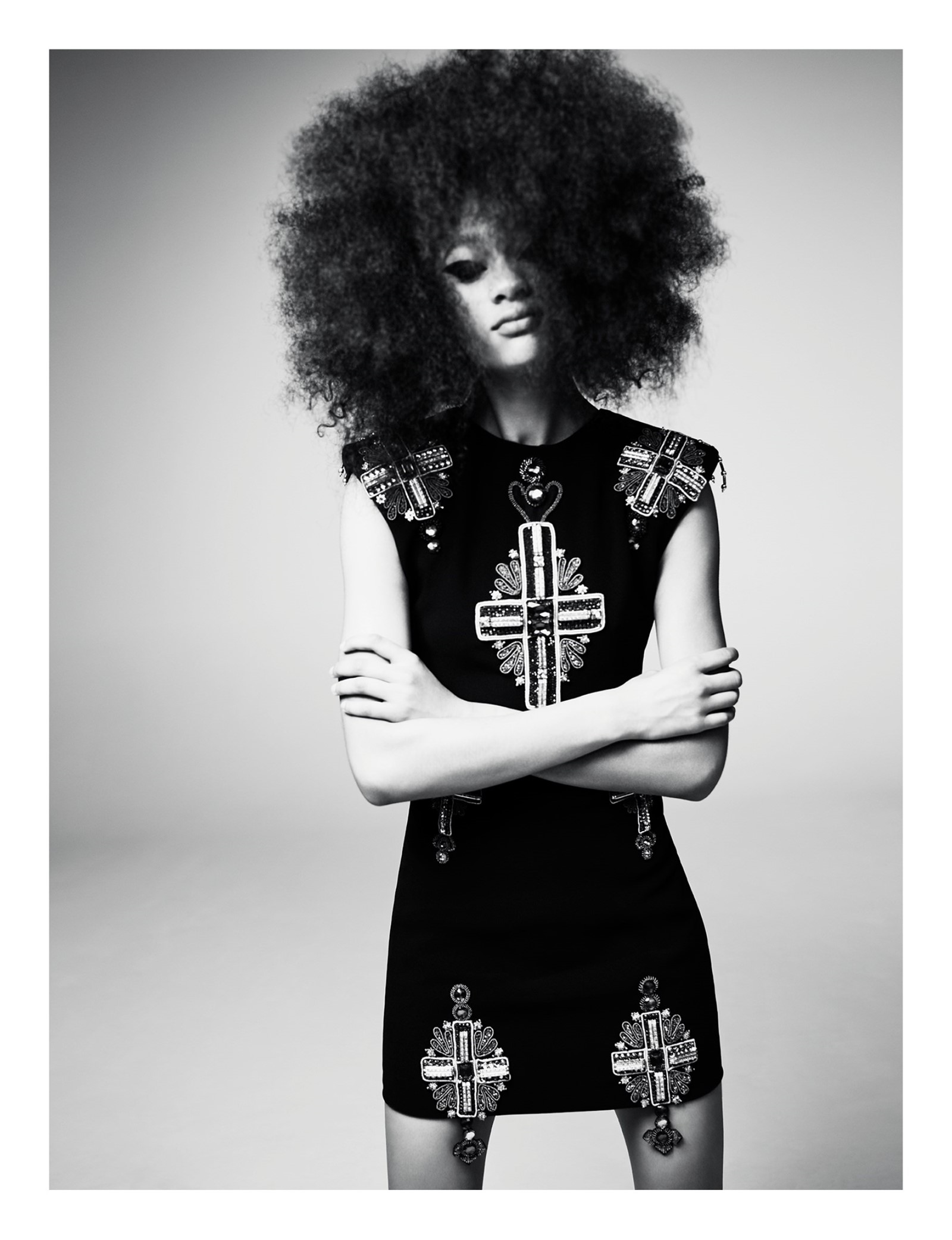

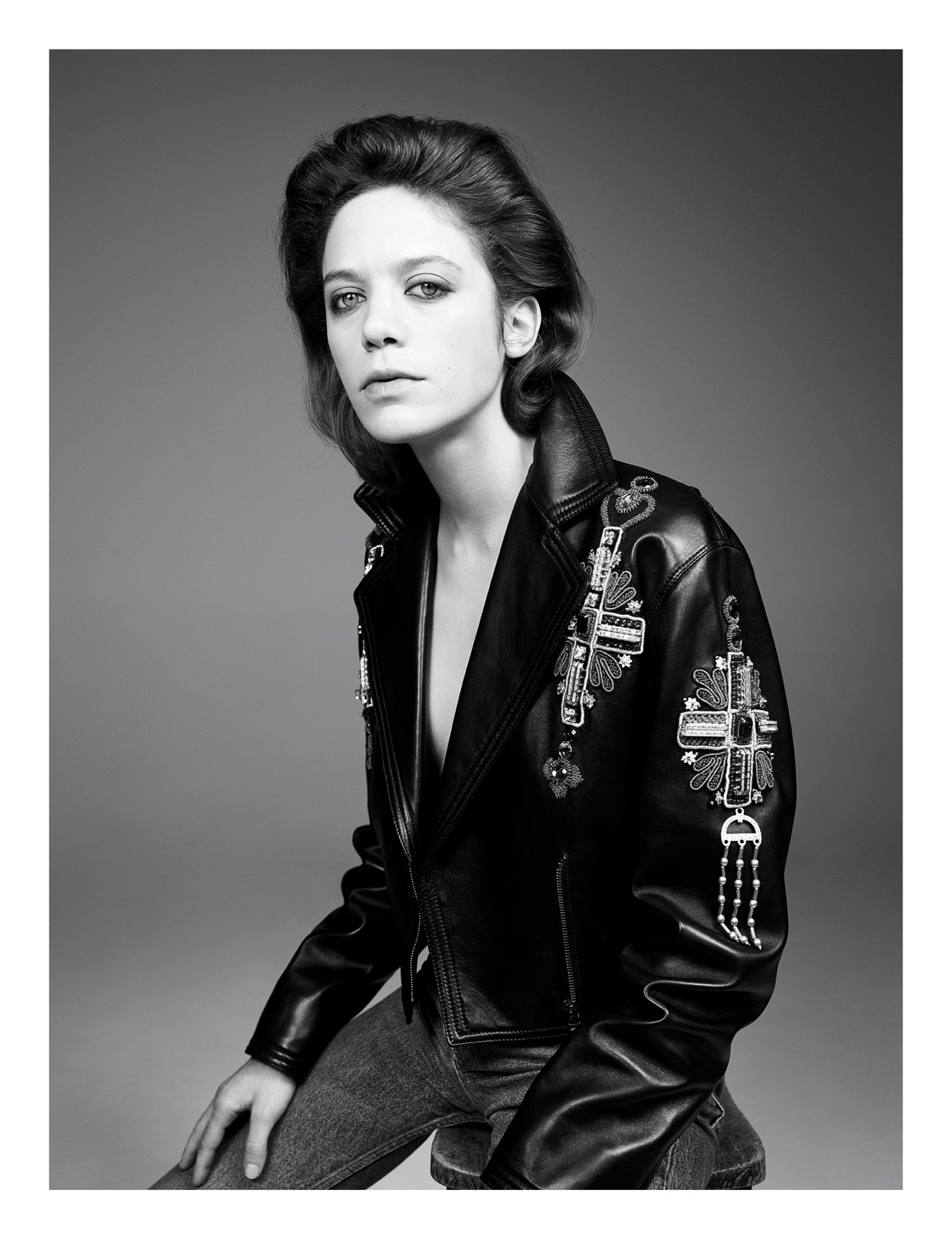

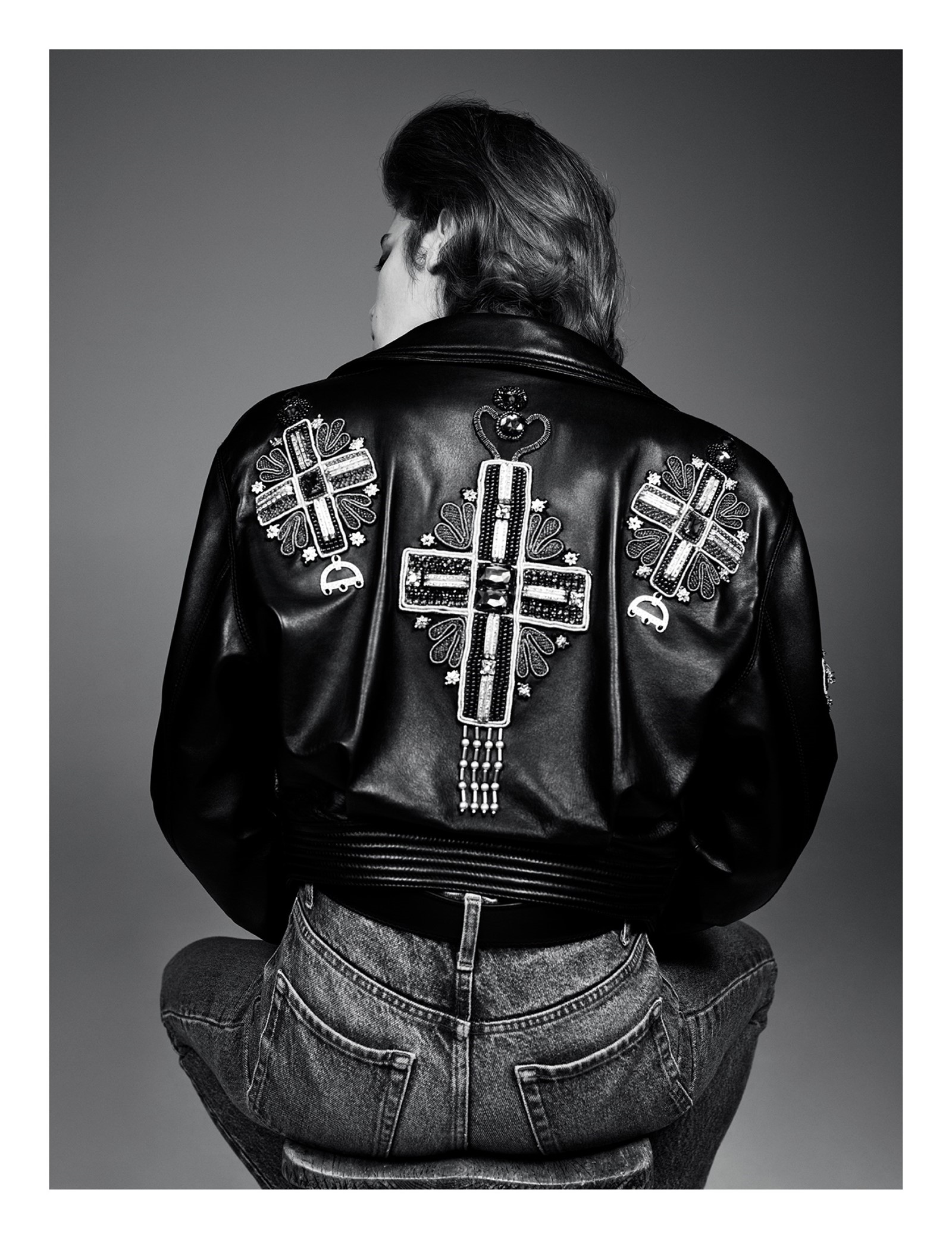

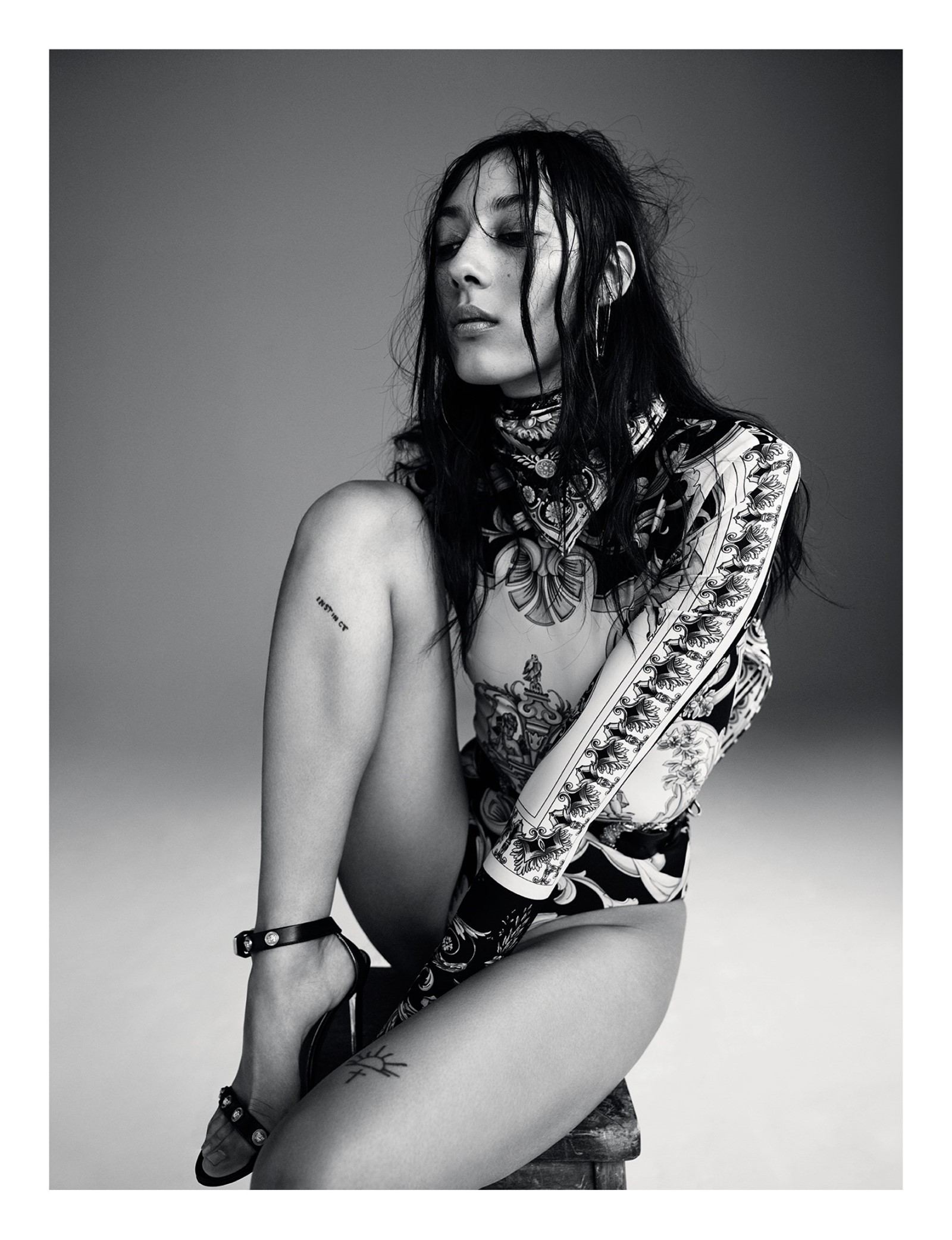

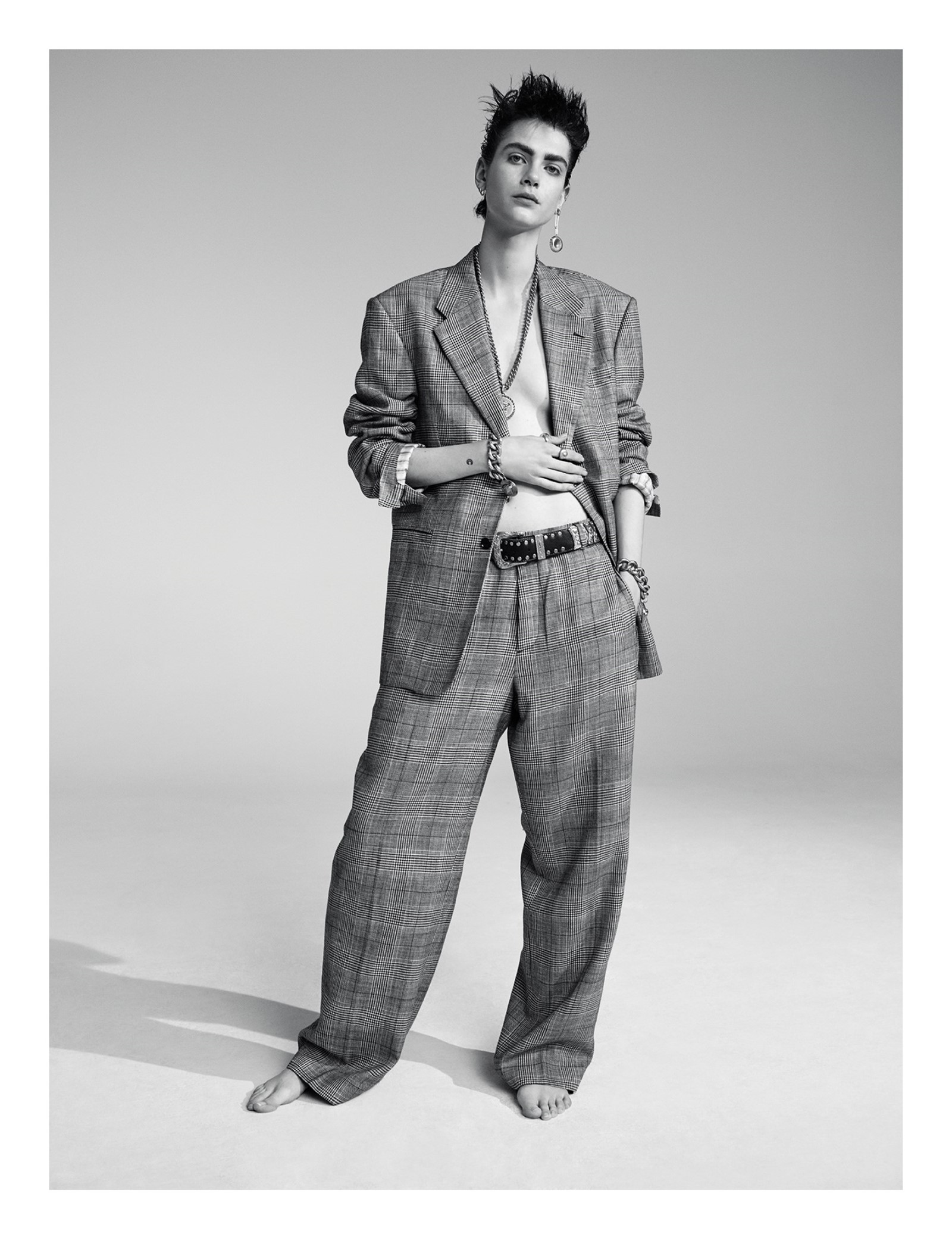

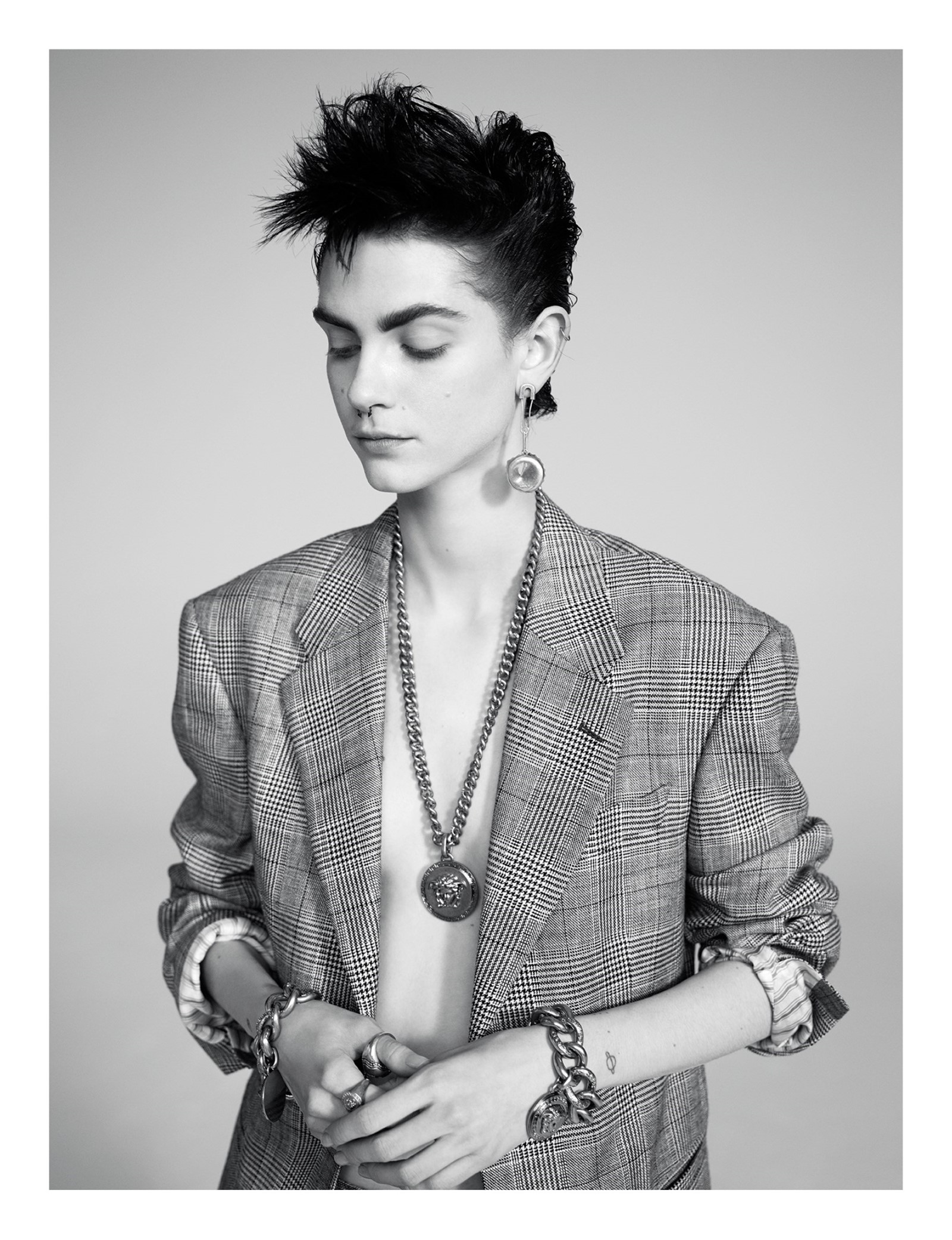

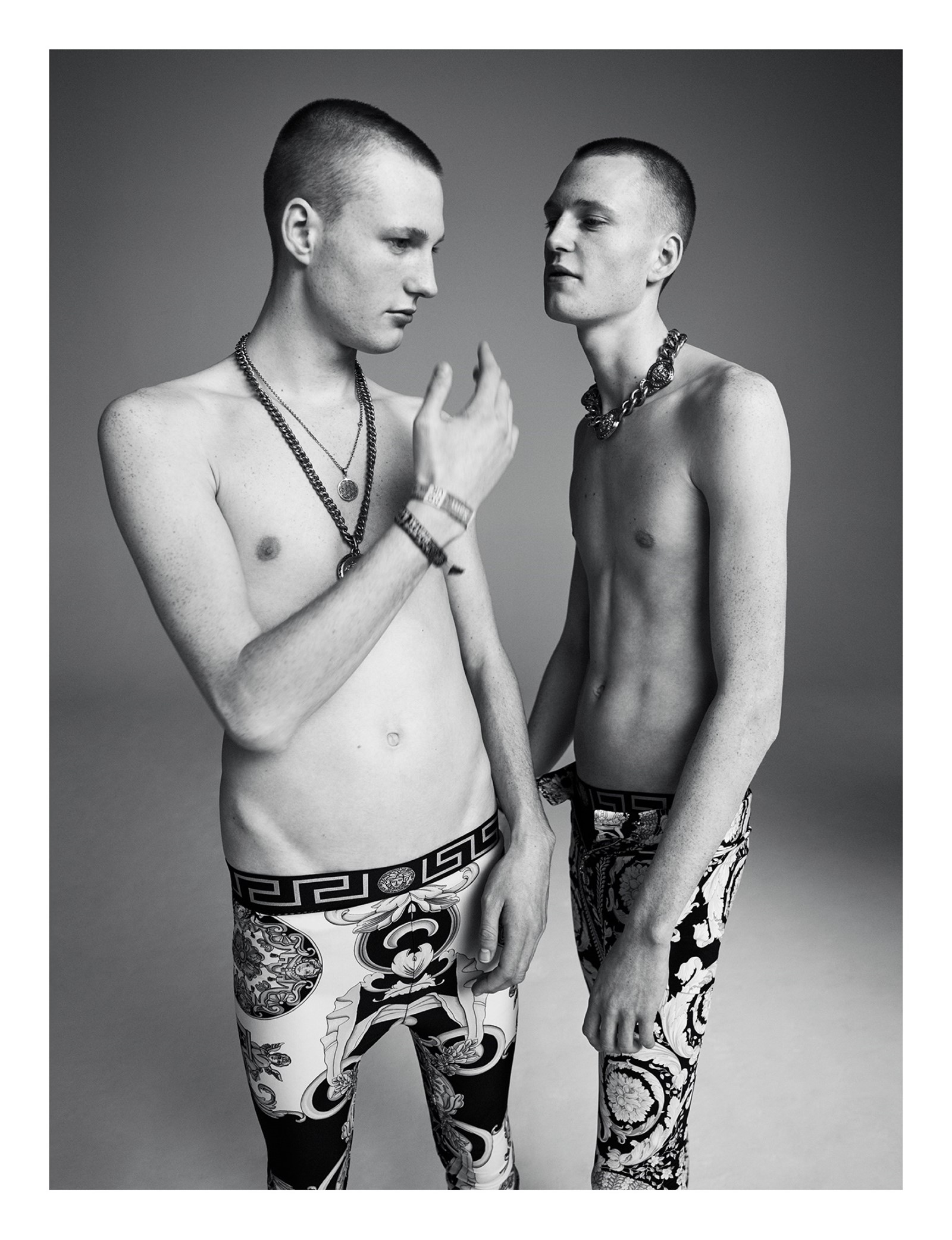

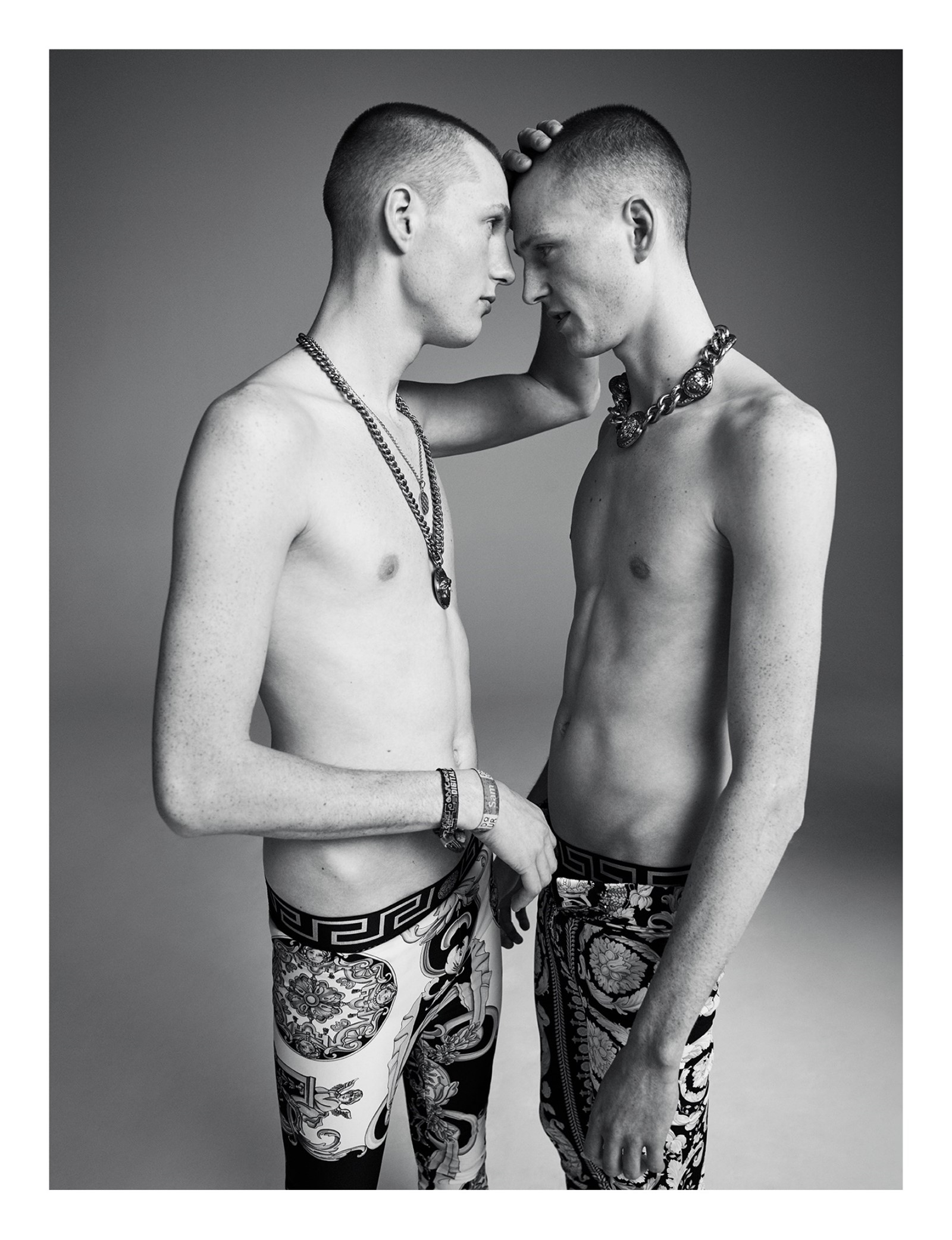

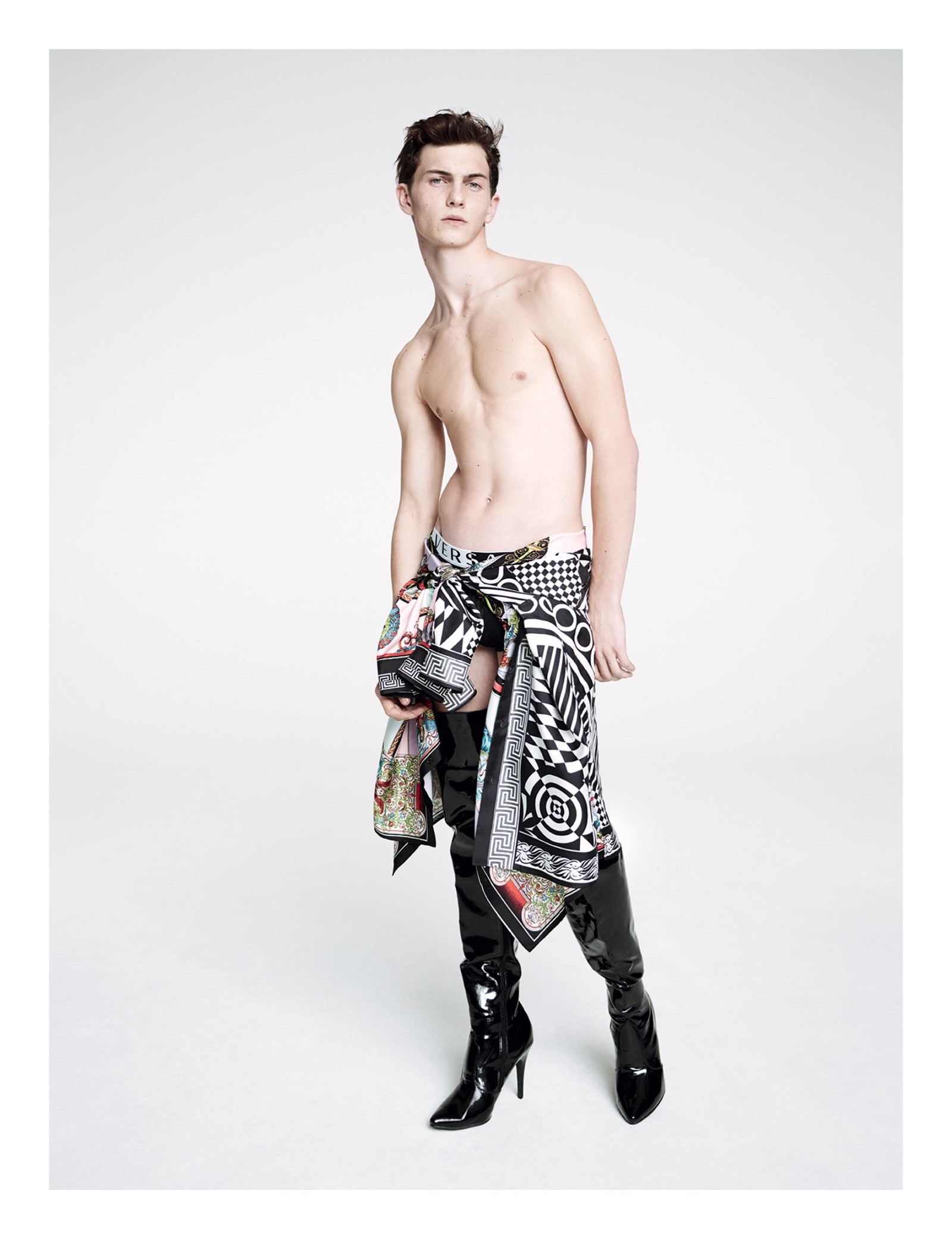

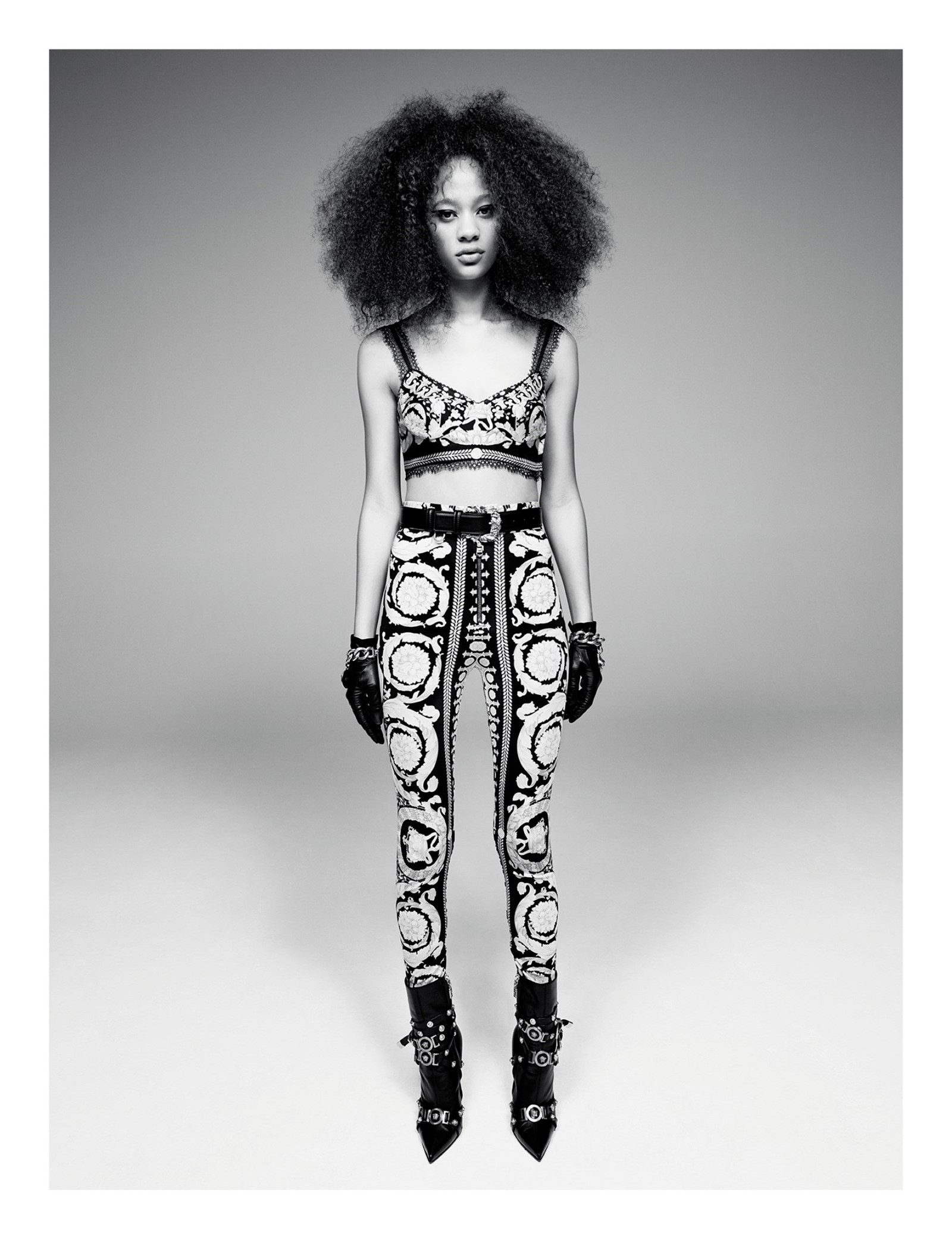

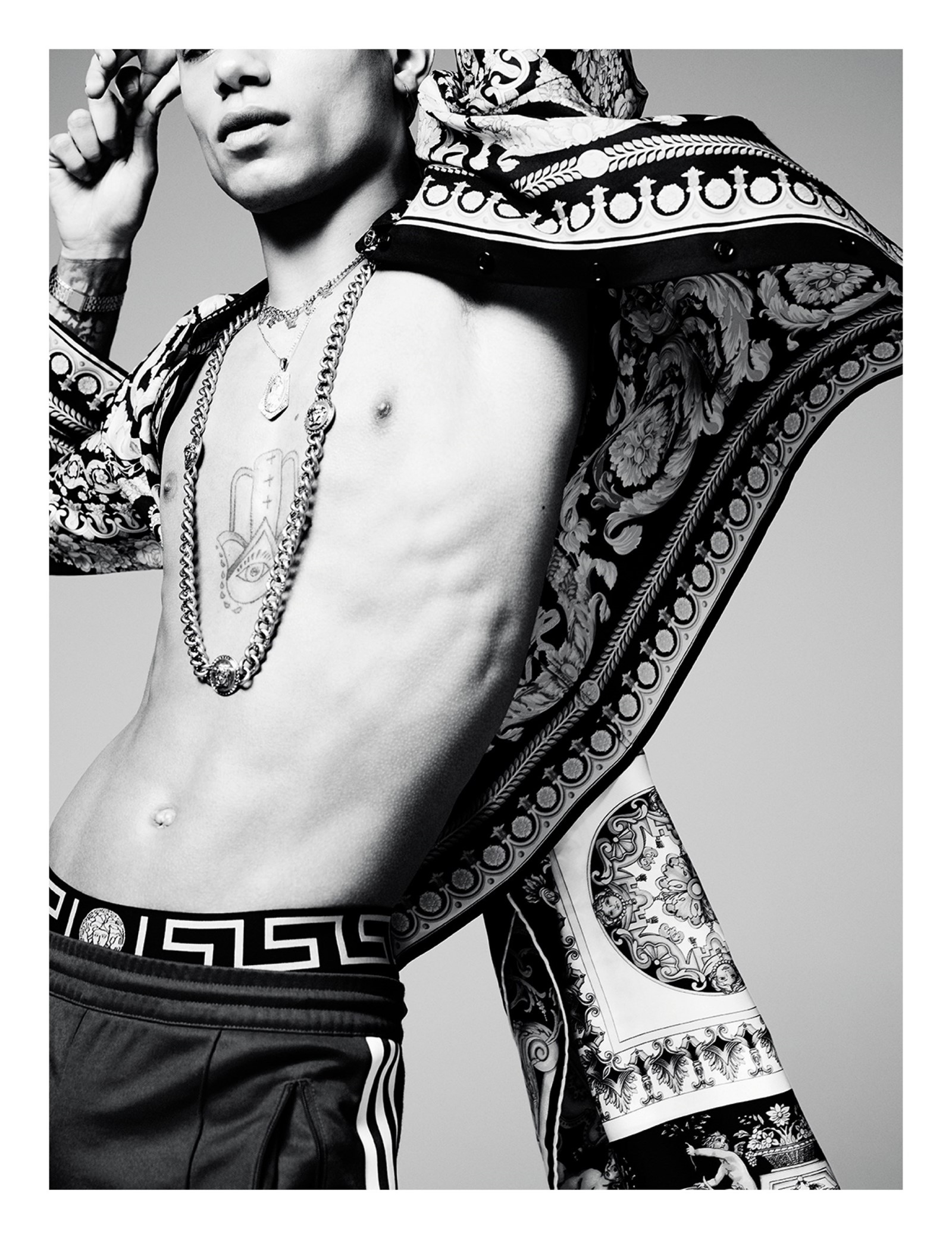

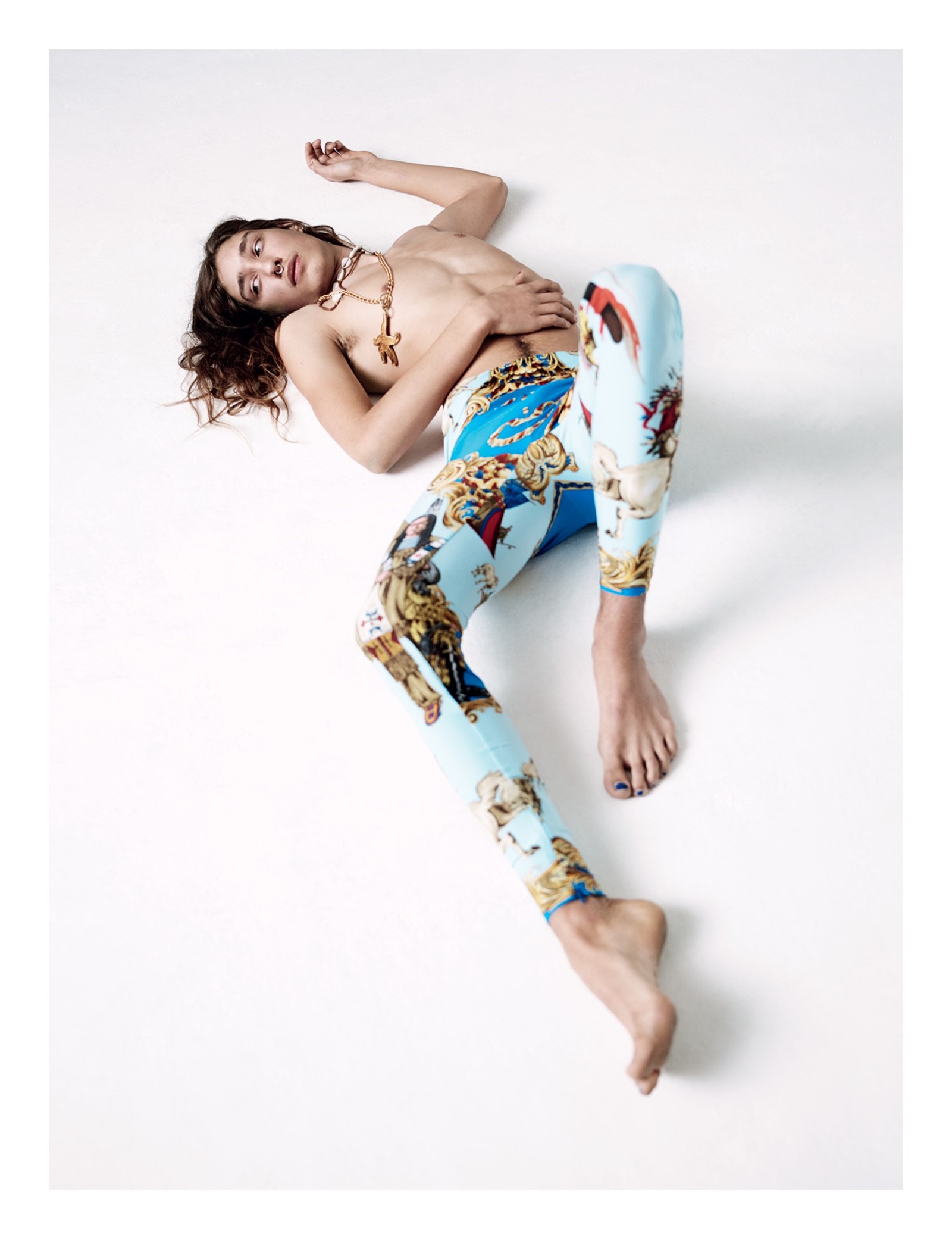

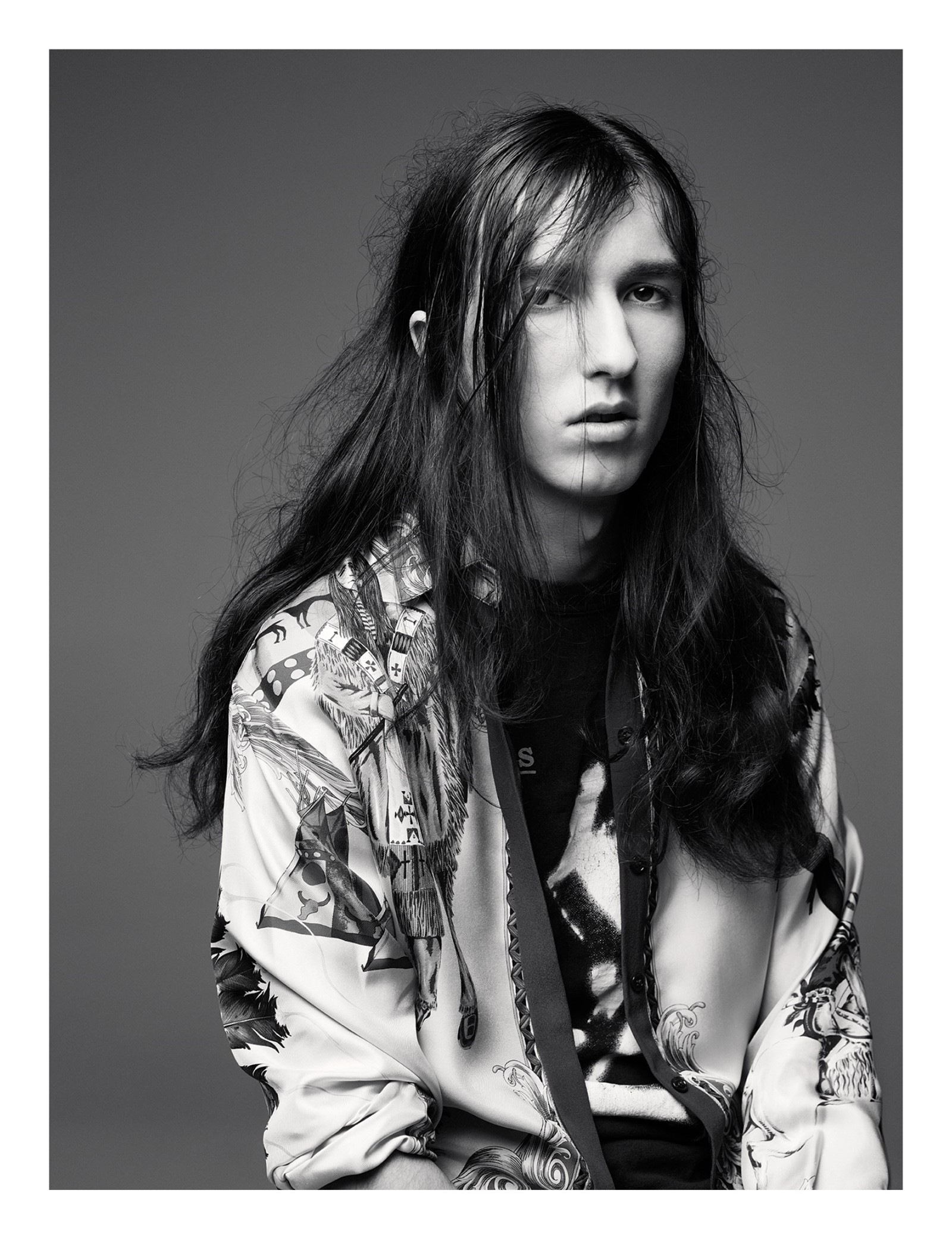

All clothing from the Versace Spring/Summer 2018 men’s and women’s collections

An audience with Donatella Versace is a little like meeting the Pope – because Italians regard fashion almost next to godliness (slightly below food); because Versace’s Milanese headquarters are as richly anointed with gilt and pietra dura marbles as the hallowed halls of the Vatican; and because Donatella Versace herself greets you with a beatific smile, clad in her ceremonial robes. Although said robes are usually tight black dresses and platform shoes; and you’re never invited to kiss her 20-carat canary-diamond ring. At least, I haven’t been.

If the Catholic Church is perceived as an institution in decline, the house of Versace was, in the past, tarred with a similar brush. In July 1997, Gianni Versace, the founder of the label, was murdered outside his Miami mansion, Casa Casuarina. Donatella Versace took over in his stead, at a point when Versace’s signatures – exuberant, aerodynamic shapes, excessive prints, a strident Mediterranean sexuality and the fusion of rock and couture on the bombastic bodies of the supermodels – had been superseded by minimalism, heroin chic and the superwaif. Under Donatella Versace, the label Gianni Versace founded in 1978 has weathered financial restructuring, multiple recessions, the oscillating vagaries of fashion and the demands of a new digital age. It has come out on top.

“I wanted to show how relevant what Gianni did can be today” – Donatella Versace

At 62, Donatella Versace now presides over one of the most famous Italian fashion houses. The house of Versace was also, once, the home of Gianni Versace: Donatella doesn’t live in the snug, low-ceilinged rooms huddled under the studio space on the third floor of 12 Via Gesù, all molasses-coloured marble and richly carved stone. Gianni bought the place, a 16th-century palazzo formerly home to the Rizzolis, the Milanese publishing family, in the first flush of his independent success in 1981. The Medusa head on the door gave his then-nascent fashion label its now instantly identifiable logo. Today, in an alcove next to a piece of ancient Greek statuary, sit two new additions, a sofa and chair from a furniture line created by Versace in collaboration with the Haas Brothers. In hammered brass and black leather, these resemble a cross between a Las Vegas slot machine and a sadomasochistic torture device. Glitz meeting sex. Very Versace.

Alongside all that showy exuberance is the intimacy of a family, an essential component to the Versace story. Though in 2014, Blackstone Group, a private equity firm, bought a 20 per cent stake, the house of Versace remains very much a family affair. Gianni’s niece Allegra – Donatella’s daughter – inherited 50 per cent of her uncle’s empire on her 18th birthday; the other shareholders are Versace’s brother Santo, and Donatella herself. As a name, Versace sits easily among the dynasties of the Borgias and Medicis, even the Montagues and Capulets. Versace’s warring household, alike in dignity, is Armani – the two were bitter rivals in the 80s, different in sensibility but vying for the same marketplace, then slightly less crowded, of newly wealthy urbanites with the urge to splurge. They were also, ideologically, trying to assert what Italian fashion should stand for at the end of the 20th century, when Milan emerged as the first serious challenge to the supremacy of Paris on the subject of all matters sartorial. Giorgio Armani argued for a pared-back aesthetic reminiscent of the purist architecture of Milan; Versace, invariably known simply as Gianni, was about extravagance and extremity, bold shapes, bright colour, vibrant print. Given that the Versaces were born and raised amid the strictures of post-war Italy, in the impoverished southern city of Reggio Calabria on the very tip of the country’s kicking boot, ironically the word rich is the only suitable adjective to describe the label. Today, it’s still based in that baroque palazzo.

Despite appearances (and perhaps, its own convictions) to the contrary, Versace is neither the biggest nor richest fashion house in Italy. It never has been. Its evening-focused clothes were outstripped in the 80s by Armani’s universal daytime appeal, and in the 90s by Gucci and Prada. Nevertheless Versace has always punched far above its weight. Armani transformed the way people dressed; Prada inverted luxury; Gucci transmogrified the marketing of the whole bundle – yet Versace seismically shifted perceptions of fashion as a whole. Versace changed not only fashion, but pop culture. It was the first high-fashion label to leap into bed with music, both dressing the musicians and staging fashion shows with all the panache of rock concerts; and Gianni Versace launched the notion of the supermodel as super-celebrity, paying a bunch of perfectly hard-bodied women astronomical fees to appear exclusively in his highly choreographed and intricately orchestrated Milanese catwalk shows and, simultaneously, giving them the star power hitherto only afforded to musicians. In March 1991, Gianni sent a phalanx comprising Linda Evangelista, Cindy Crawford, Naomi Campbell and Christy Turlington along his klieg-lit catwalk, mouthing to George Michael’s Freedom! ’90, in imitation of the song’s model-heavy David Fincher-directed music video then still in constant MTV rotation. The audience erupted in hysterical applause.

“I was Gianni’s disturber. I wasn’t a muse. I was the one who made Gianni think. I’d never say I like it right away. ‘You can do better. You know you can do better than this. Don’t be afraid’” – Donatella Versace

“That was a moment in fashion!” states Donatella Versace, emphatically. “When fashion was art… ” She pauses, reassesses. “When fashion was rock and roll. Rock and roll was – is – a big part of Versace inspiration.” That’s an interesting assertion. We talk twice, in the balmy Milan heat of early June, just before her latest menswear outing and while Versace is still devising the Spring/Summer 2018 womenswear show marking her 20th year as the label’s creative director, and again in November, a few weeks after the reception of the latter. Like a rock band in its confident prime, Donatella decreed it was time for a greatest hits compilation. Madonna has modelled for Versace campaigns twice, under both Gianni and Donatella; Spring/Summer 2018 was Versace’s immaculate collection.

Bring up the anniversary, and Donatella halts the conversation. It’s not about celebrating her achievement in bringing the company back to rude health, nor the fact she has now been at the helm longer than Gianni Versace himself. “For me, it’s 20 years since my brother passed away,” she says. Her voice is thick – not her accent, but the actual vowels and consonants. They catch in the throat. “And it’s sad. It’s still sad.” Yet that wasn’t the feeling that translated through the resulting collection, an unapologetic tribute, utilising a tight edit of pieces and a clutch of prints exhumed from the Versace archives and giving them new life. The designs in question hailed from the early 90s – Gianni’s heyday – when his shows were packed with supermodels and his stores frequently emptied of clothes by frenzied shoppers.

She didn’t touch Gianni Versace’s final collection – his Autumn/Winter 1997 Atelier Versace haute couture show, presented over the swimming pool of the Ritz in Paris that July, days before his death. “My favourite collection of Gianni’s was his last, the one with the crosses, the Byzantine one, but that’s too close to what people, young designers are doing today,” says Donatella. The crosses she did reissue were blockier, rockier, from that Autumn/Winter 1991 ready-to-wear show – the one with the supermodel moment, which appropriately Donatella reprised for her own finale of Carla Bruni, Claudia Schiffer, Naomi Campbell, Cindy Crawford and Helena Christensen in golden dresses composed of the Oroton metal mesh Gianni introduced in 1982.

Donatella has delved into the house’s history before – she’s referenced the signature Versace Baroque prints liberally and updated that Oroton mesh for her own evening gowns – but, she says, had never actually visited the label’s archives in Novara, a small city an hour’s drive west of Milan, to re-examine the clothes Gianni made. She’d never paid such overt homage to her late brother’s talents. Now seemed like the right time. There were even a few pieces taken directly from the archive: bejewelled handbags; a skirt from the Autumn/Winter 1992 collection fringed with thousands of rouleau strips of chiffon, whose laborious structure meant the original could not be reproduced. “It’s incredible. You cannot do this kind of thing today. It’s impossible. It would cost a fortune,” says the unexpectedly practical queen of Italian excess, in a moment of paradoxical frugality. The collection was marked by prints: Gianni used 22 colours in his silkscreens and printed both sides of the fabric – unheard of luxuries even today. “When I started to think of print, I think of Baroque, Animalier, but when I saw the Pop print, the Marilyn, the Vogues, I found them so refreshing,” says Donatella Versace. “It’s so happy, so joyful.” The prints were original, but the shapes were updated: the proportions of everything were retooled, re-engineered, from the supermodel proportions of the early 90s. “I didn’t know how tight the waist was of those models, and how big the boobs were!” says Donatella. “The body was different then. It was really different. Big shoulders, you know? And a very womanly body. Even the heels of the shoes, I changed.” Donatella herself is obsessed with shoes, perennially jacked up on platforms. She made her new-old heels a little higher.

“I wanted to show how relevant what Gianni did can be today,” she says – and the collection did just that, underlining how modern these clothes seem, and how referenced Versace is. Mirroring Donatella Versace’s first solo show of September 1997, where fellow designers including Miuccia Prada, Karl Lagerfeld, the Fendi sisters and Giorgio Armani sat in the audience as a show of support, the designers Alessandro Michele of Gucci and Anthony Vaccarello of Saint Laurent attended her show. It seems that they were acknowledging, tacitly or not, the inspiration of Gianni behind their multiple, multicoloured swirling prints and hyper-short, sexualised silhouettes, respectively.

The show soundtrack was specially composed by the Portuguese musician Inês Coutinho, performing under the name Violet Friends, with lyrics based on Donatella’s own recollections of her brother. “This is a celebration of a genius,” began the track, as a quartet of models prowled out in Versace’s Autumn/Winter 1991 Baroque and Spring/Summer 1992 Animalier printed silks. “This is a celebration of my brother.” Donatella wrote the lyrics. “She was telling me, ‘Talk about Gianni, talk to me about Gianni, talk to me about Gianni’,” recalls Versace about devising the soundtrack with Coutinho. “And I said, ‘I don’t really think I can.’ But she said, ‘You know, just put it in your way, in your words.’ I cannot write a song. I’m not a songwriter. Everything was … was hard, to do. Emotionally.” She pauses. “But it was for him.”

Donatella Versace is curled up on a plump leather sofa, bolstered by signature Versace barocco-meets-big-cat-print pillows, in Gianni’s golden apartment. It’s a place heavy with memories, for her. “We would have dinner parties, we would have the biggest drama, biggest fights,” Donatella says. “And the biggest love. And we were like this working together, two different people. Gianni and me – we were totally different people. You know, everything started here.” She has her hair bobbed short, soft and studiously messily. It’s a volte-face to the perennial image of her as the singular “Donatella”, toned and tanned and trussed in evening wear, hair the colour of flax and as straight as al dente spaghetti tugged far down her torso in two panes, like an old master painting. That visual shorthand is so strong, it has often veered into caricature: she’s the only fashion designer to have been impersonated on RuPaul’s Drag Race; the comedian Maya Rudolph has a running skit of her on Saturday Night Live. Donatella, apparently, phoned up her doppelgänger and told her her jewellery didn’t look expensive enough.

That image of Donatella was established alongside Gianni in the early 90s. She began bowing beside him on the catwalk of the Versus show, a second line whose reins Versace handed to Donatella to design, potentially preparing her to inherit his mantle when the time came (which, as it happens, was sooner than ever anticipated). In this period, her creative role was commonly glossed over: she was usually described as his muse, a word she hates. “I was Gianni’s disturber. I wasn’t a muse. I was the one who made Gianni think,” Donatella says. “I’d never say I like it right away. ‘We can do bett …’” she pauses, again. “‘You can do better. You know you can do better than this. Don’t be afraid.’”

Donatella Versace never wanted to be a fashion designer: she was both pulled and pushed into the position. Pulled by her brother, Gianni, who relied on her as his right-hand woman; and pushed into the limelight, alone, 20 years ago by circumstances beyond her control. At other inherited fashion houses – Dior, say, or Balenciaga – there is little direct connection between the current creative director and the label’s founder. There are shared aesthetics, hidden similarities, mutual quirks. Certainly never a bloodline.

“I’m a woman. And if I’m a woman, I’m not Gianni. Finally I said, ‘I’m going to do different things’” – Donatella Versace

There’s more than just blood at Palazzo Versace – Donatella Versace is the physical embodiment of the label’s aesthetic. She always has been – a decade older, it was Gianni who first bleached Donatella’s hair, gave her her first high heels and evening dresses, and took her to gay discos in their home town. She originally studied languages at university in Florence, but migrated north, to Milan, where her brother was designing clothes for a string of Italian manufacturer’s labels (Callaghan, Complice, Genny) in the 70s. It’s then that the 20-something Donatella started to be seen as Gianni’s muse, inspiring his collections and wearing them too.

How did those clothes feel? Donatella’s face breaks into a wide, genuine smile. “Amazing! I felt amazing. I thought I looked fucking fabulous.” Then she throws back her head, and laughs, hard. Before she sips from a green straw thrust into one of those transparent plastic Starbucks cups. Only, looking again, you realise it’s a crystal-etched Versace glass, the Starbucks mermaid replaced with a Medusa.

Versace’s Medusas were absent for a while: Donatella Versace distanced herself from the aesthetic that defined Versace’s heyday, when the business ballooned to rake in close to a billion dollars in revenue and when Versace’s shows, campaigns and clothes were the flashiest in fashiondom. Times changed, just as Versace faced a crisis of identity, and Donatella Versace a profound personal tragedy. She acknowledges, today, there were rocky moments. “Honestly in the first five, six years that I was at the house, I was so confused,” she says. “And I didn’t do well. I didn’t do well because some people were telling me, ‘You worked with Gianni, try to do what Gianni was doing, try to be as close to him as you can.’ But there were things I couldn’t do because I’m a woman. And if I’m a woman, I’m not Gianni. And finally I said, ‘I’m going to do different things’. People didn’t take it, they didn’t understand so well. It took almost nine years, I think.” She stops. “Seven, to nine, I don’t know, maybe not. For the press, especially. Because the thing is, every show was a comparison with my brother. And I keep telling them ‘I’m not my brother!’ My brother was a genius, my brother – I’m not him. This is who I am.”

Bearing that in mind, Donatella Versace’s tribute collection is even more remarkable, more touching. It demonstrates a new-found confidence in her own abilities as a designer, to stand alongside the legacy of her brother. For all her endearing and engaging self-deprecation, hopefully Donatella Versace realises that she has earned that: when fashion once again turned to excess at the dawn of the millennium, Donatella Versace dressed Jennifer Lopez in a glorified bathing suit, vajazzled about the crotch and elongated into a barely there, baring-everything evening gown. Frantic Internet searches for photographs of it prompted the invention of Google Image Search. That’s a hefty legacy all of her own, one decidedly for the modern age, which Versace (via Donatella) has wholeheartedly embraced. The house of Versace’s best work – under both brother and sister – has been in a similar vein of exuberant luxury, the kind of style that slips in and out of fashion and is never a particularly easy sell. But it’s always fun.

I have interviewed Donatella Versace a number of times. We know each other fairly well, in the pas de deux of interviewer and subject. Donatella Versace isn’t a Medusa, rather a sphinx. She reveals a lot, it seems, without revealing very much at all. She is guarded – literally (in the aftermath of Gianni Versace’s death, the family began to be trailed by security details; so did other prominent fashion designers), but also metaphorically. You never feel, entirely, that you unravel Donatella Versace, for all the genuine bonhomie and wink-wink nudge-nudge innuendo punctuating the stuffiness that pervades many interviews. That’s because no one can really understand her point of view, the warring emotions. Grief mingled with pride, passion mixed with duty. Every anniversary of her various achievements is, equally, a milestone of loss.

But, for Spring/Summer 2018, something has softened, both discernibly and imperceptibly. Donatella Versace has relaxed. A weight feels lifted. She is certainly more prepared to talk about Gianni Versace – a name and person that, often, an interviewer would shy away from directly mentioning. The floodgates have been opened – today, Donatella Versace wants to remember. She laughs, a lot – unexpectedly; engaging, joyful.

“It was fun,” Donatella says, of her time working with her brother. It’s a word she uses often, along with happy. “I remember the last show of Gianni in Paris. We were singing, both of us, we were singing the music of the show – loud – and people were looking at us, and saying ‘they’re crazy, these two!’” She laughs. “We were so happy that day, and I remember it like it was yesterday. I want to remember Gianni like that. The last day we’d be together, doing the show in Paris, that collection. He was killed five days later. It was July, in Paris. I left the Hôtel Ritz and went outside to say goodbye.”

It was the last time she saw her brother. “Gianni had the best models, and he did that amazing collection. Byzantine with all the crosses. He went, the next day, he was taking the Concorde – which was still there! – to go to New York, and then to Miami, and said, ‘I’ll see you in three days.’ Because I was supposed to go there, in three or four days.” Donatella Versace exhales.

“The way he died, it was horrible, but still, the joy, and the passion, and everything. I want especially for young people to know.” Donatella Versace’s voice softens. Warms. “He was amazing.”

Hair: Eugene Souleiman at Streeters using Wella Professionals. Make-up: Lucia Pieroni at Streeters using Clé de Peau Beauté. Models: Luc Defont at Success Models, Clara Deshayes and Selena Forrest at Next, Wolf Gillespie, Paul Hameline at Success Models, Hannah Motler at Premier Models, Reece King at SUPA, Ayobami Okekunle at IMG Models, Gaia Orgeas at Anti-Agency, Christopher R and Philipp R at Tomorrow Is Another Day, Anthon Raimund, Amandine Renard at Models1, Harry Smith and Shea Wild at D1 Models. Casting: Jess Hallett at Streeters. Set design: Emma Roach at Streeters. Manicure: Ama Quashie at CLM Hair and Make-up using YSL Beauté. Digital tech: Henri Coutant. Lighting: Romain Dubus. Photographic assistants: Benjamin Coppola and Pedro Faria. Styling assistants: James Campbell and Lydia Simpson. Hair assistants: Alfie Sackett, Sky Cripps-Jackson and Shiori Takahashi. Make-up assistants: Mirijana Vasovic and Lois Moorcroft. Casting assistant: Caitlin Prosser. Set-design assistant: Sam Risky. Manicure assistants: Sylvie Macmillan and Elysia Rose. Production: Rosco Production. Post-production: TripleLutz