By definition, the womenswear shows should always be about, and for, women. However this season, Autumn/Winter 2018, amid the daily dialogues surrounding the very real practicalities of women’s lives today, designers’ dedications to femininity feel a little more pertinent than usual. With creatives pooling direct inspiration from all kinds of memorable women – politicians, intellectuals, actresses, artists, socialites, dancers and the downright plain stylish – what has emerged is a deliciously diverse portrait of the gender they’ve long been dressing. Inspiration was sought out from characters whose vocations, personalities and styles varied wildly, and their legacies were transported and reinterpreted to outfit the women of today. Here, we look to several of these women, who are continually awe-inspiring.

Cloaking Katharine Hepburn at Salvatore Ferragamo

“In England I’m sure they didn’t think anything at all,” the actress Katharine Hepburn once said to The New York Times of her preference for trousers over a skirt. “In California I think they just thought I was queer.” Hepburn, in much of her life was a woman who dared – and her clothing choices were no different, favouring the clean, practical cuts of masculine garments that would mark the beginnings of the American sportswear look. Not that the haughty, matter-of-fact Hepburn would have considered herself a pioneer – “I’ve just done what I damn well wanted to,” she said.

For shoes, Hepburn favoured Salvatore Ferragamo, of whom she was a treasured client – and for A/W18, designer Paul Andrew, half a century on, looked back to her legacy. He was fascinated with what he called her “naughty pedigree” – comparing her clipped New England tone and wealthy upbringing to Princess Margaret, or, more specifically, Vanessa Kirby’s portrayal of the British Royal in The Crown. It made for a collection that tossed up masculine and feminine – roomy tailoring worn with leather riding boots à la Hepburn sat alongside stitched-together silk scarves and neat velvet dresses that nodded to the princess’ aristocratic charm.

Erdem’s ode to Adele Astaire

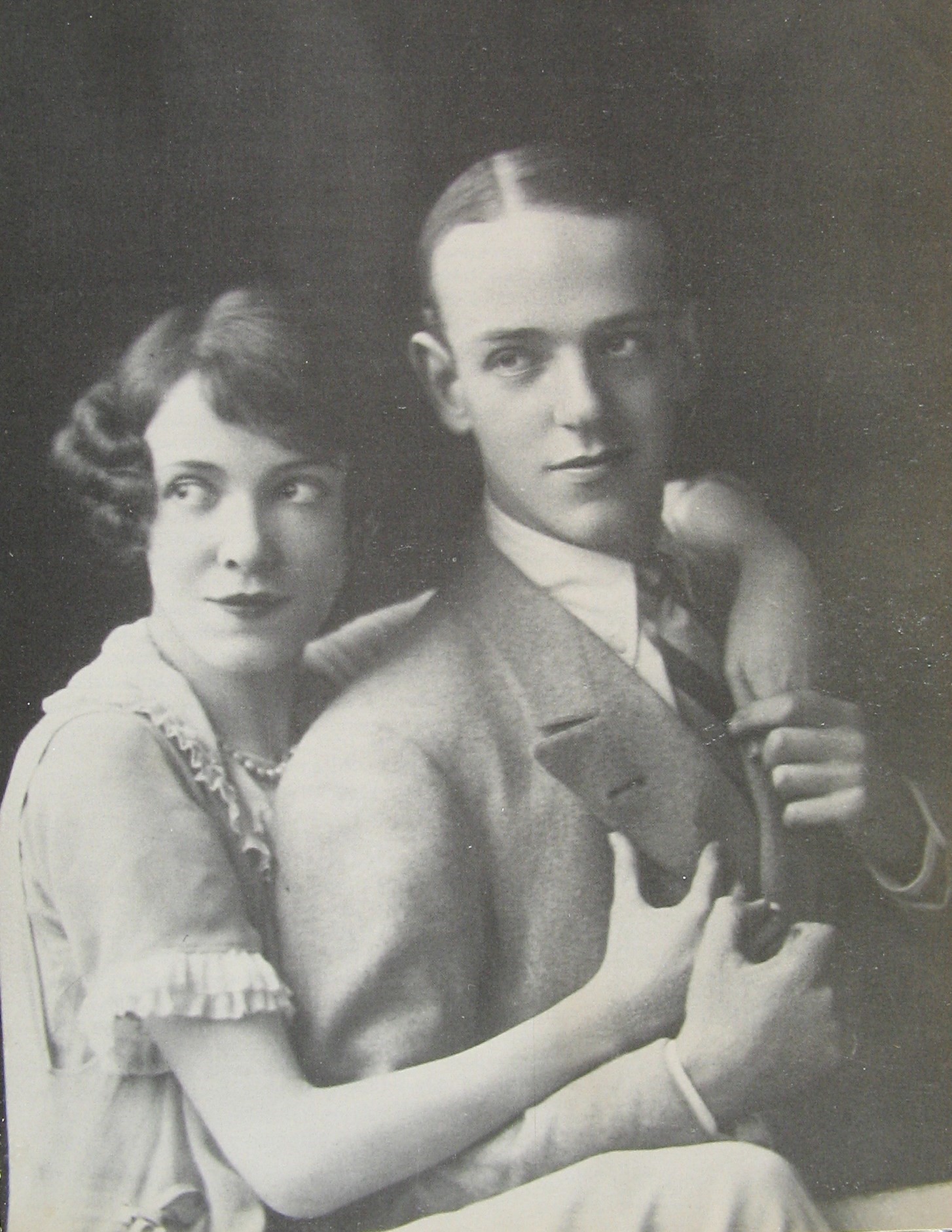

The 76 or so years that he ruled over film and television have caused the surname ‘Astaire’ to become almost inseparable from the first name ‘Fred’, the all-singing, all-dancing actor and choreographer who became one of the most influential dancers in history. But as is so often the case with supremely influential men, his time firmly in the spotlight caused another Astaire to be cast into the shadows – in this case, his older, and ostensibly more talented, sister Adele.

Adele and Fred Astaire, born ‘Austerlitz’, trained in theatre and vaudeville together, their mother acting on a teacher’s recommendation that they might have a stage career, and performed as an ensemble for many years on Broadway and later in London from early childhood until their 20s. It wasn’t until Fred moved to Hollywood and established himself as a success there that Adele, reluctant to risk being eclipsed by his reputation, distanced her career from his, forgoing dancing on camera altogether in favour of the stage.

Adele eventually retired from the stage to marry the aristocratic Lord Charles Cavendish and moved to Lismore Castle in Ireland, and it is this dichotomy – of the glitzy showgirl, a transatlantic theatrical success, clad in spangly costumes, and the aristocratic countryside wife – that inspired London designer Erdem Moralioglu to base his A/W18 collection on her. “I became obsessed with this girl,” he explained backstage, “and I kept coming back to the idea of her – such a showgirl – imagining her in her tweed and her glitzy star-spangled capes, traipsing the moors. Or, if she wore her flapper dresses with something belonging to her husband.” Her influence transpired in floral brocades, elaborate veils, fur coats, tweed capes, and country manor-ready gowns – the ultimate collision of Hollywood and the Irish countryside.

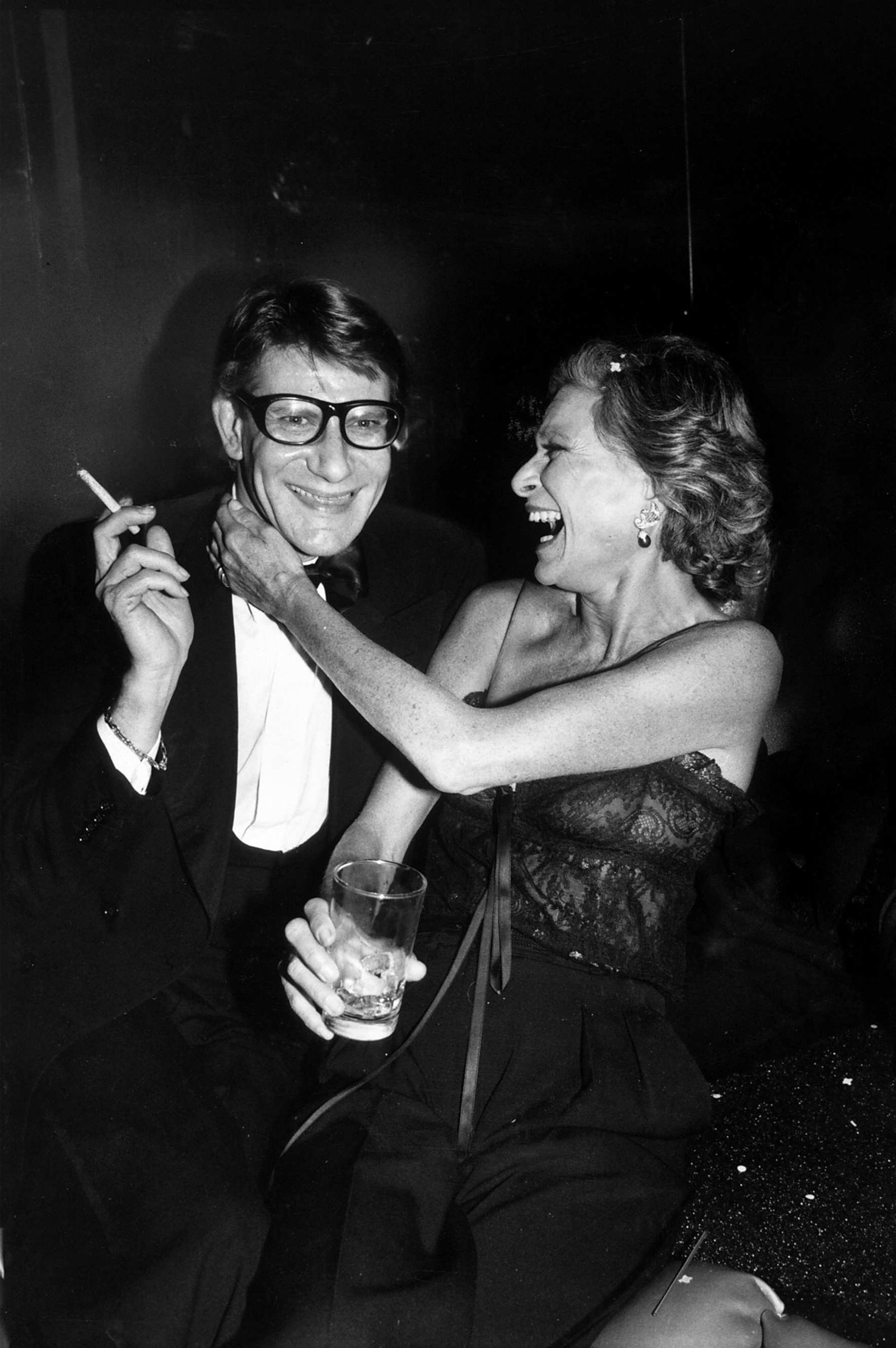

Remembering rule-breaking Nan Kempner at Halpern

Who better to epitomise Michael Halpern’s glamour-suffused collections than New York’s legendary disco queen, Nan Kempner? For this, the designer’s first, tentative step away from sequins – jacquard tailoring, in zebra print, was introduced, so too a fuzzy, fil coupé fabric – he called on the legendary evening when Kempner was turned away from nightspot Le Cirque for her Yves Saint Laurent trouser suit. “She went away, took off the pants, and went in wearing the jacket as the dress,” the designer explained backstage, citing her as one of fashion’s great rule-breakers – “inappropriate dressing,” was the maxim for his own collection.

Kempner, herself an insatiable shopper – much thanks to her wealthy husband Thomas Loeb, of investment bankers Loeb Partners – racked up a fabled collection of original Saint Laurent, a designer of whom she was an avid fan. (In 1994, she reported that she had only missed one of the designer’s 63 collections.) Her legacy lives on in her wry sense of humour – “I tell people all the time I want to be buried naked. I know there will be a store where I’m going,” was one such quip – but also for her deep love of fashion, and belief in the transformative power of a well-chosen outfit, passed on to the world with brief careers at Harper’s Bazaar and Vogue Paris. “I’ve always liked being noticed, and I work hard at it,” she once said. “Frankly, I couldn’t go mail a letter if I didn’t feel I looked all right.”

A sonnet to Gertrude Stein at Shrimps

American multi-hyphenate Gertrude Stein was many things – a novelist, poet, playwright and prolific art collector, whose patronage of Modernist artists and thinkers in Paris in the early part of the 20th century kickstarted several careers. A style icon, however, she was not – a fact which makes her influence upon Shrimps’ Hannah Weiland for A/W18 all the more captivating. The London-based designer turned to romance for her theme this season; it manifested in a deluge of reds and pinks and floral prints to pay a sweetly graphic homage to the power of love. But in the short pixie-like crops, voluminous fur silhouettes, and eccentric, off-kilter proportions, Weiland also paid tribute to Stein.

Her homage could be felt most directly in the designer’s appropriation of the now ubiquitous “Rose is a rose is a rose” – a line extrapolated by Stein from Shakespeare’s “a rose by any other name…”, – largely understood to be a reflection on the “thingness” of a thing. It’s opaque, even by Stein’s avant-garde standards. Here Weiland replaced ‘rose’ with ‘shrimp’ (because, why not?) – and plastered the reworked saying across the walls of the presentation room – but the fact of her having chosen this fragment at all is quite romantic: it became a well-recognised fragment in part because it was selected as a favourite line by Stein’s partner in love and life, Alice B. Toklas, who herself used it often to decorate plates and suchlike. A romantic gesture indeed.

Jeremy Scott’s reimagining of Jackie Kennedy Onassis

Jacqueline Lee ‘Jackie’ Kennedy Onassis (née Bouvier) is hardly an original fashion inspiration. Famed for her style, elegance and grace – publically showcased first on the arm of the 35th president of the United States, John F Kennedy, then on Greek shipping magnate Aristotle Onassis’ – she’s been revered for her dress sense since she was crowned debutante of the year in 1947. Her pink suit – the Chanel bouclé tweed skirt suit with matching pillbox hat – the blood-spattered ensemble she refused to take off after President Kennedy’s assassination, is now emblematic of that historic event. The suit was donated to the National Archives and Records Administration in 1964, under the terms of an agreement with Jackie’s daughter, Caroline Kennedy, determining that it will not be placed on public display until 2103. Its infamy was illustrated beautifully in Pablo Larraín’s recent film Jackie.

And though, technically, it was the late Onassis’ style that informed Jeremy Scott’s latest outing for Moschino, the designer came about his assembly of 60s skirt suits (including the pink, worn by Kaia Gerber) and carefully carved Jackie wigs by way of a more unorthodox narrative: that of an alien cover-up. Satisfying his perennial penchant for a gag, he turned to a JFK conspiracy – insisting that President Kennedy had revealed to Marilyn Monroe, in the throes of pillow talk, that aliens were in fact real; evidence of which was found at the Roswell UFO crash site in the New Mexico desert. The story goes that she was ready to go to the press with the issue and thus had to be bumped off – as he was a year later too. From here, Scott pursued the story of Jackie the undercover alien, responsible for both their deaths.

Cue a battalion of boldly hued business suits worn by blue-, yellow- and green-skinned women. Print nods to the pop art of Warhol and Lichtenstein emerged too, playing on ideas of glamour, celebrity and consumerist culture with Skittles logos, and sweets, plastered onto dresses and accessories. Known for his stance on Trump, this nod to First Lady fashion floated a bigger message too: “I’m not anti-alien,” he said. “I don’t want to build a wall.”

Thom Browne’s tribute to Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun

Among her predominantly male Rococo and Neoclassical artist peers in 18th- and 19th-century France, Élisabeth-Louise Vigée Le Brun was something of a trailblazer. Besides the fact that she had no right to an art education (being a woman), she was born a peasant yet managed to work her way up in Paris’ esteemed art world, eventually becoming portrait painter to Marie Antoinette and establishing herself in court. Vigée Le Brun’s paintings of Marie Antoinette are her most famed, due to her lightness of brushstroke (typical of Rococo art) and of personality conveyed in the pieces, at odds with the rumoured lifestyle of the French queen and with the political turmoil that was on the horizon for Paris.

For A/W18, Thom Browne found a muse in this art world pioneer. He presented his collection in a space that riffed on an artist’s studio, with easels dotted among show-goers and models weaving between them. Browne’s modern day vision of Vigée Le Brun is an introspective one, in which the artist is “painting a vision of what she wanted to be in the 21st century,” he said. Textures reminiscent of Le Brun’s wispy, billowing style of painting were sent down the runway as part of the desginer’s signature complex tailoring, on jackets, dresses and suits rendered in varying grey hues: fur cuffs, intricately crafted flowers, sheer sleeves and delicate, dangling beading. Structurally, some clothes harked back to a time of more restricted dressing, with waistlines clearly accentuated before hips jut out, and boning connoting corsetry further still. The woman that Browne sent down the catwalk is an idiosyncratic rule-breaker, aware of what’s expected but readily subverting those tropes – certainly evoking Vigée Le Brun for the 21st century.

Appreciation for Stéphane Audran at Chloé

French film and TV actress Stéphane Audran made her name playing cool, clipped and criminally chic wealthy women in the 60s and 70s. Clad in Karl Lagerfeld’s Chloé – expertly knotted, monogrammed silk neckerchiefs, crisp trench coats, fur trimmed duffles and velvet hair bows – she rose to fame in Les Cousins, the 1959 hit directed by Claude Chabrol whom she later married (they were together for 16 years). She starred in more than a dozen of his movies including Les Bonnes Femmes (1960), played a wealthy woman involved in a ménage à trois that goes awry in Les Biches (1968), The Unfaithful Wife (1969), played a school teacher in rural France in Le Boucher (1970), and Betty (1992, filmed 12 years after she and Chabrol separated). Her ice-queen charisma made her an easy choice for Luis Buñuel’s The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie, a Surrealist depiction of a shared pursuit for a perfect dinner party.

Natacha Ramsay-Levi called her second collection for Chloé a study in “the frustrated desires of the bourgeoisie”, making Audran a key muse alongside Anjelica Huston, Isabelle Huppert and Sissy Spacek. Returning to looks in the Chloé archive, Ramsay-Levi first looked to Monsieur Lagerfeld’s time at the house, as well as his love of French cinema. “It was a very 1970s house, very bourgeois and perfect in a way – but with Karl, it becomes a bit scandalous with the things he was playing with.” So ensued a collection that balanced the urbane with the sensuous and easy: silks in 70s earth tones, elegant arm cuffs pushed up to form puffed sleeves, hairy coats, lace-up boots and zippered bootleg trousers. Any touch of the retro was updated with a sense of futurism and warrior-worthy gowns. “I want her to be very strong, but you can’t really reach her,” Ramsay-Levi said.