Watched by Andy Warhol and Liza Minnelli, 1973’s Battle of Versailles marked the emergence of New York’s designers onto the world stage

The year is 1973, and the venerable couturiers of France – Hubert de Givenchy, Yves Saint Laurent, Marc Bohan (then of Christian Dior), Emanuel Ungaro and Pierre Cardin – continue to rule over fashion. But the world is changing, not least in the way women are choosing to dress. Fresh from the 1960s, they are as likely wearing clothes for the dancefloor as the street: a year later, disco would reach the top of the Billboard charts; by 1977, Studio 54 would open its doors.

As if symbolic, Paris’ Palace of Versailles, the opulent status symbol of French craft built by Louis XIV (such opulence that it would eventually light the match of revolution, and destroy the French monarchy in the process) was, by the 1970s, crumbling. Rooms were left open to the elements, or flooded; drafts ran down corridors; the grand drawing rooms were left dilapidated. $60 million was the figure estimated needed to restore it to its former glory – a figure that the French government could simply not afford.

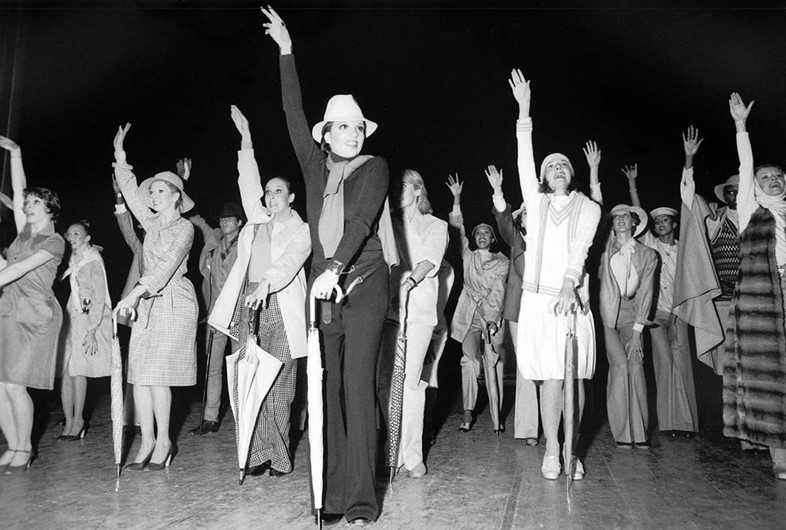

And so begins the story of the Battle of Versailles, a fashion show of such extravagance it reads as if somebody could have made it up entirely. Organised by publicist Eleanor Lambert in an attempt to raise funds for the embattled palace, the concept was simple: those five French couturiers would go head-to-head with their American opposites – Halston, Oscar de la Renta, Anne Klein, Bill Blass and Stephen Burrows. Held in 1973 in Théâtre Gabriel, Versailles’ grand auditorium, and bookended with performances by Josephine Baker and Liza Minnelli, each designer would show eight looks to represent their country. At the end, a winner would be chosen.

There are moments that creep up on you, altering the course of fashion unexpectedly, but this was not one. With an audience including both Princess Grace and Grace Jones, Andy Warhol and Elizabeth Taylor, the Battle of Versailles was always fated to be legendary. And it did change fashion, loudly and inalterably, ushering in a new era when American designers and the diverse models they chose would rule supreme. As critic Robin Givhan deemed it, it was “the night American fashion stumbled into the spotlight”.

The Show

Taking place on November 28th, and attended by a primarily French audience, the Battle of Versailles began with levels of indulgence that would have likely pleased former palace resident Marie Antoinette. The French contingent put on a show designed to celebrate the extravagance and intricacy of Parisian couture, set to a backdrop that included, among other things, a gypsy carriage pulled by a rhinoceros, a rocket, a full-length limousine and models being carried in the arms of drag queens.

The clothes themselves were similarly ornate, containing all the brushstrokes that have since ensured haute couture’s survival – sprays of feather, Lesage beading, rich fabrications, layers of flounce and froth. The American designers, in part down to a lack of money and the three months they had to prepare, went for a wholly more pared-back approach. They chose to set their collections against a single backdrop: the slim lines of a drawing of the Eiffel Tower.

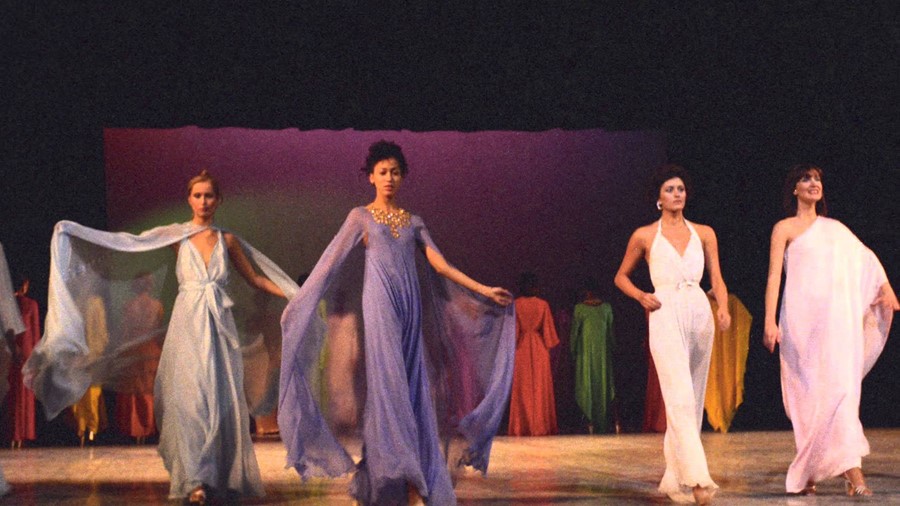

Their designs followed suit, rejecting the ostentation of their French competitors with clothing that favoured clean lines, vivid colour and nods to the growing necessity of function. The new approach thrilled the French audience who were impressed not only with the grace of the American designers’ clothing but the way it moved – exemplified with the models gestures, a precursor to Vogueing, birthed on New York City’s dancefloors. It paid off: by the end of the evening, the American upstarts would go away with the prize.

The People

The guest list for the evening read like a who’s who of the 1970s; Andy Warhol flew in from New York for the occasion, joining an assembly of socialites, celebrities, burlesque stars and drag queens. Naturally, such a gathering made for a clashing of egos – Minnelli, who opened the American section with a playful performance of Bonjour Paris! purportedly refused to attend unless Raquel Welch was disinvited; Halston began referring to himself in third person.

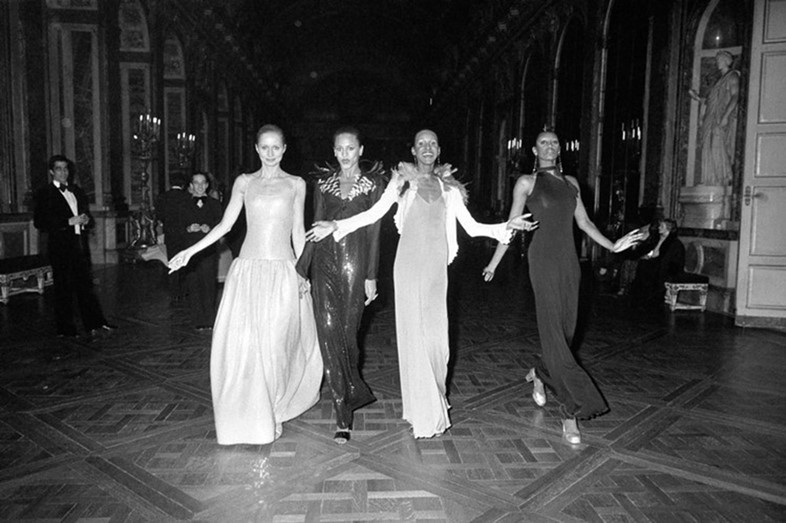

But by far the most interesting faces were the American models, who unexpectedly championed a new, statuesque beauty that was far away from the constraining traditions of French fashion. Of 36 models who walked for America, 11 were black women – a first for the era. Not least among them was Pat Cleveland, who would go on to be something of a poster-child for 1970s New York, and then the fashion world at large.

It was much of the reason that America enjoyed success, providing a newness that fashion craved and needed. It was exemplified too in the designers themselves – take Stephen Burrows, who grew up in Newark, New Jersey, far away from the gilded salons of Paris. Yet it was his clothing that stole the show, inspired by the drug-laced nightclubs of New York, the pieces were designed to move: his signature “lettuce hem” – layers of chiffons, topstitched at the edges – looked best when spun around on a dancefloor. “The most distinctive element of Mr Burrows’ clothes,” wrote The New York Times, “is that they looked as if they left the house around midnight to wind up the next afternoon a crumpled heap on some bedroom floor at an address the wearer was probably not all that familiar with 24 hours earlier.”

The Impact

Distilled best in Robin Givhan’s 2015 book on the subject, the Battle of Versailles will be remembered not for the celebrity attendees, but for the five American designers catapulted to world renown by it. (Some, like Oscar de la Renta, remain in business today.)

“American fashion, and the women who wore it, did not have to aspire to perfection in order to be dynamic and alluring,” she writes. “Clothes could be practical, accessible and simple. They could be fun. A woman could be free. She could be an individual.”

More than that, though, it signalled a move – for a time at least – towards the growing presence of women of colour in fashion. Later that year, Hubert de Givenchy would travel to California to scout black models to walk in his own shows. Combined with the emergence of disco, and Motown before, a new standard of beauty seemed at least possible, if not fully realised. “The default standard of beauty had always been white, and it remains so,” Givhan writes.

What the Battle of Versailles did make clear, in a historically befitting setting, was that fashion was ready for revolution – and it was the energetic new era of American designers, and their muses, that would be leading the charge.

Visitors to Versailles (1682–1789) runs until July 29, 2018 at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.