Though controversial, Gaultier’s S/S94 collection was an exhilarating collage of what he saw on the street, at once evoking Eastern mysticism and raising the spirit of Joan of Arc

In the month Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination opens at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, anothermag.com is running a series of The Shows That Matter on collections that tackled religion, head on. Here, in the final part, Jack Moss looks back to Jean Paul Gaultier S/S94, where the provocative designer channelled the spirit of Joan of Arc.

Of the many interpretations of this year’s Met Gala theme, Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination – taken from the title of the Costume Institute exhibition with which it coincides – perhaps the most du jour were those attendees who channelled the indomitable warrior spirit of Joan of Arc. After all, what more suitable dress-up for current times than Catholicism’s rare female superhero? (In a recent piece for Vogue, “What if Joan of Arc went to the Met Ball?”, Lynn Yaeger would deem her the gala’s unofficial muse.)

Those who grew up in France are well versed in the tale of Saint Joan. Though not consecrated until the 1920s, she was a figure of devotion long before, and many villages will proudly assert their place in the martyr’s narrative; most of those will have a statue, or stained glass window, to prove it. Doubtless her story would not likely have passed by a young Jean Paul Gaultier, a designer who would himself become an iconoclastic figure of Frenchness, albeit on different terms: the proclaimed enfant terrible of Parisian fashion.

Religion has long seeped into Gaultier’s collections, often to controversial effect: most famously, his A/W93 show, entitled Chic Rabbis, saw him reinterpret the dress of the Hasidic Jewish community, an exercise which allegedly ended with a chorus of boos. Controversy came too with his close friendship and working relationship with Madonna, herself an expert in drawing on religious symbolism, gleaned from her Catholic upbringing, to inform her own less-than-sacred pop culture iconography and playful provocation. On the release of her Like a Prayer video – a ecstatic declaration of liturgical pleasures, complete with the singer writhing, negligee-clad in a church – she revealed her ambition to become a nun as a child.

Gaultier’s approach to religion was similarly lively – he would dress up as the Pope for the saturated lens of French photographer Jean-Marie Périer in 1994, when he was at the peak of his powers and relishing his status as fashion’s provocateur. In 1990, he had dressed Madonna in the infamous cone bra for her Blond Ambition tour; two years later he hosted an amfAR benefit fashion show which raised $700,000 for AIDS research. (Madonna would appear here too, walking the runway bare-breasted.) In the seasons between, Gaultier’s collections were that rare thing: creative and commercially viable, a favourite among celebrities and editors alike.

Les Tatouages, though, his S/S94 show named for the plethora of trompe l’oeil tattoo prints which ran throughout (designs were also stencilled on to the model’s bodies) would become the era’s defining show for Gaultier, with Vogue selecting it as one of 25 unforgettable shows of the 1990s. Though he would address religion more explicitly in later collections – his Couture 2007 collection saw each model come with their own halo, and riffed on ecclesiastical dress – here, he melded disparate visions of spirituality: Eastern mysticism, the wild spirit of punk and the devotional, armour-clad figure of Joan of Arc. “His Postmodern sensibility is always to transform, surrendering cognitive command of the past to an intuitive sensibility for the present,” writes fashion historian Richard Harrison Martin.

The Show

If the 1990s were a particularly furtive period in Paris fashion – in 1995, John Galliano would take the top job at Givenchy; in 1996, Comme des Garçons would show its convention-defying “lumps and bumps” Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body collection – Gaultier’s shows, in the early half of the decade at least, were something of the nexus of the week.

“He [Gaultier] was absolutely peerless for the longest time in the late 80s and early 90s,” critic Tim Blanks told The New York Times. “Each show was an absolutely remarkable hybrid of fashion and social comment. The sense of event that surrounded fashion was very different from the sense of event that surrounds it now. It was much more like a cult band inspiring this incredible devotion. The crowd would be full of drag queens and cult rock stars and things.”

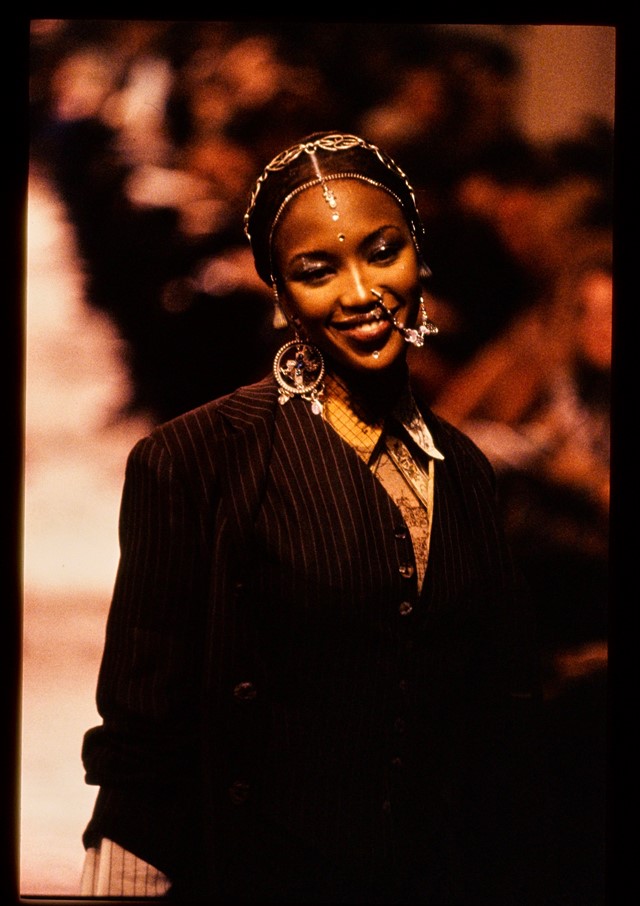

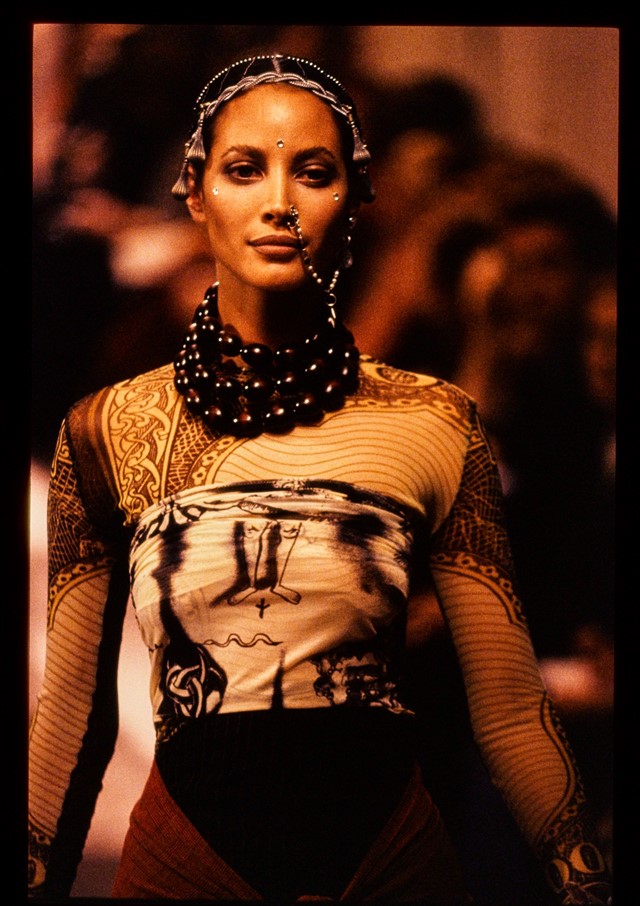

Such was certainly the case for his S/S94 show. Guests were likely greeted with the smell of joss sticks, lit backstage and later carried down the runway in models’ hands, a hint to what Vogue would deem Gaultier’s “a startling vision of cross-cultural harmony”. Such suggestions of “global village chic” – again, according to Vogue – namely, traditional Indian jewellery (nose rings were connected to ears by chains) African tribal prints and beading, would reasonably raise concerns of appropriation if they were to be shown now.

That said, the clashing narratives were argued by Gaultier to simply reflect what he saw on the street – the Postmodern collage of a globalised city such as Paris. In this spirit, more disparate parts still: Louis XVI brocade frock coats met playful patchworked denim, printed kilts and braces and sarong-style wrapped skirts. The New York Times saw this as Gaultier’s “homage to punk fashion”: “his wacky collection could have made you smile, but first you would have had to get past his penchant for pierced body parts,” wrote critic Bernadette Morris.

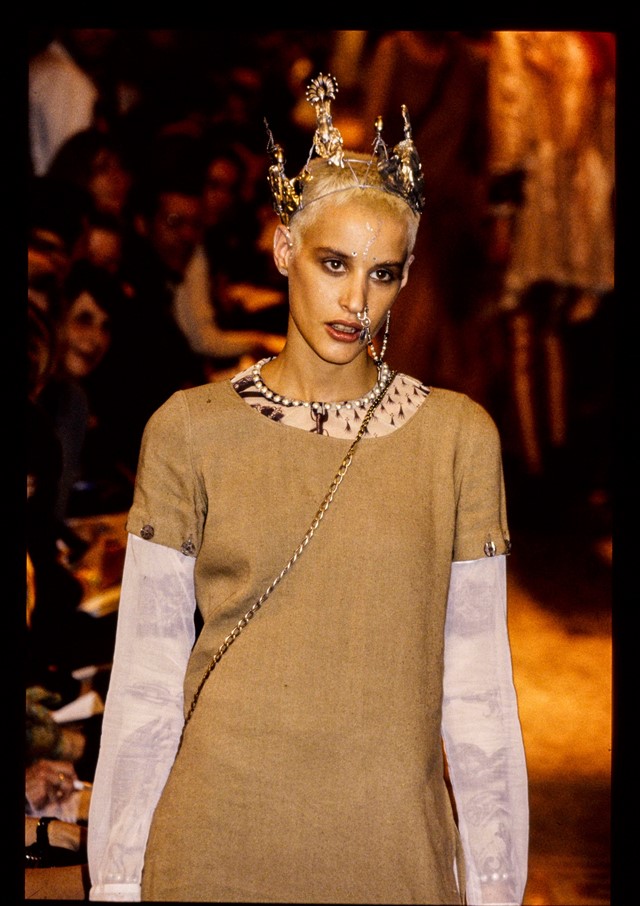

The show ended with slices of chainmail, recreated in silver sequins, fine metallic knitwear, loops of metal or, in some cases, physical panels taken from suits of armour worn over deconstructed medieval gowns and flattened corsets. In welding (in this case, physically) masculine and feminine, warrior and saint, he recalled the spectre of Joan of Arc – it’s little surprise that one of these looks now is being displayed as part of the Heavenly Bodies exhibition in New York.

The People

Gaultier was an early champion of selecting models who defied easy categorisation in terms of gender identification, body shape and race, and was just as likely to be found scouting models on the street as choosing from an agency’s boards. Such was certainly the case here, as attendees were left questioning which of the tattoos (some of which were on faces and heads) were stencilled, and which ones were real.

A number of Gaultier’s muses – some of whom continue to work with him to this day – walked in the show, notably the domineering presence of Spanish actress Rossy de Palma, made famous for her roles in the films of Pedro Almodóvar. Here, in her second look, she carried an umbrella and wore a brocade waistcoat, the shirt beneath scrawled with graffiti all making for an imposing figure. A young, shorn-haired Jenny Shimizu was also in keeping with Gaultier’s alternative vision of beauty; so too Anna Pawlowski, a model made famous walking for Yves Saint Laurent in the 1970s, who appeared with cropped hair and walked in flat leather boots.

Of course, the supermodels of the day were also in attendance – Naomi Campbell, Nadja Auermann, and Stella Tennant all walked, transformed by Gaultier’s uncompromising vision. It was Christy Turlington, though, who had the biggest transformation – usually the lithe vision of clean-cut American beauty, here she was recast by Gaultier in a tie-dyed bandeau, heavy jewellery and trailing facial piercings.

The Influence

Though his influence on both fashion and pop culture endures, Jean-Paul Gaultier is rarely spoken about with the same reverence as his contemporaries. This is often attributed to his appearance as co-presenter on satirical television show, Eurotrash, a decision the designer himself claims to have been the reason he missed out on the top job at Dior, given to John Galliano in 1996.

Nonetheless, anybody who doubts the importance of Gaultier as a designer has only to look at two designers who began in his studio in the 1980s and early 1990s: Nicolas Ghesquière, and Martin Margiela. At Balenciaga and Maison Martin Margiela, respectively, they defined the 1990s and early 2000s, and the decades since. In fact, Les Tatouages would be in part an echo of Martin Margiela’s debut collection in 1989, which in part pioneered the tattoo print – in a full circle moment, those same prints were referenced in Demna Gvasalia’s ode to Margiela at Vetements A/W18.

The collection will also be remembered for Gaultier’s ability to serve his references with a wink, borrowing, reinventing and then tranforming them into, if not entirely new clothes, an entirely new energy. His outré fashionings, both as designer and personality, made from a satisfying contrast to the cool minimalism heralded by contemporary Helmut Lang, playfully asserting the (oft-repeated) Postmodern statement that nothing is original, and everything has been done before.

For Gaultier, however, this wasn’t to be seen as a statement of defeat: by sewing together elements of past and present, with collections that traversed epochs, religions and continents, he dismantled and rebuilt the way that men and women dressed. As Ingrid Loschek writes, in Gaultier’s work “the past continues to live on in the present – and the present revives the past”.

Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination at the The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York runs from May 10 – October 8, 2018.