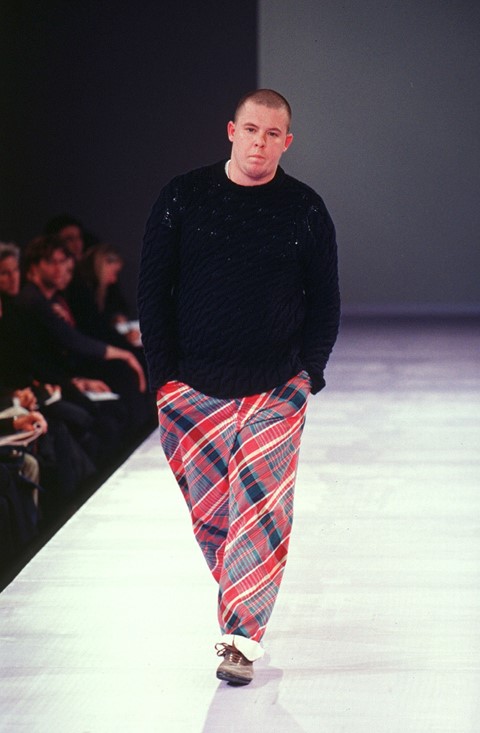

Walking as part of Comme des Garçons’ A/W97 show would become part of Lee McQueen’s lifelong love affair with Rei Kawakubo’s work

“Rei doesn’t compromise, nor should she,” said Alexander McQueen on the subject of Comme des Garçons’ Rei Kawakubo, the iconoclastic Japanese designer who continues to make her trade with baffling, brilliant clothing. “No one should compromise. Compromise makes people dull.”

If the two designers grew up continents apart – she in Tokyo, Japan, the daughter of a university lecturer; he in Stratford, London, the son of a taxi driver – their affinity became apparent in their work, and the fascinations they shared. Chief of those was the body – in their hands it was a site of transformation, warping it into strange, violent new forms with their clothing. Both too would find themselves operating on the edges of darkness, attempting to respond to an oftentimes inhospitable world with cloth.

McQueen’s own love of Kawakubo, though, could perhaps be attributed to a simpler fact: Comme des Garçons made up much of his own personal wardrobe. In her menswear – frequently less conceptually challenging that her womenswear – he found the clothes that would become his working uniform, numbering baggy, striped cotton shirts, raw denim jeans and unstructured tailoring, in vast proportions, a play on the shapes of traditional Japanese garments.

“I remember going to the Brook Street store years ago now,” McQueen said. “You felt so unwanted that you wanted to be wanted. I bought a Comme des Garçons striped shirt for £129. Why was it special? It had ‘Comme des Garçons’ on the label.” You cannot help but wonder if the appeal of Comme’s menswear for McQueen was the way it played with normality – in the late 1990s Hilary Alexander wrote in The Daily Telegraph: “tousle-haired, unshaven, [he was] wearing a strange conglomeration of what turned out to be a Comme des Garçons shirt and ‘Bosnian’ combat pants.”

Just days after his first show as creative director for Givenchy, in 1997, he would find himself at the call of Kawakubo – asked by the designer to step on to the other side of the runway, and walk for Comme des Garçons Homme Plus’ A/W97 show which was to be held at Paris’ Musée National des Arts d’Afrique et d’Océanie. McQueen agreed, and opened, wearing a large black sweater and roomy plaid pants – not far and away from the clothes he wears in candid photographs of the time. It followed a number of other significant cameos on the Homme Plus catwalk: artist Jean-Michel Basquiat for S/S88, director John Waters for A/W92 and actor Dennis Hopper for A/W91.

The journalist Stephen Todd, who was profiling McQueen for Australian gay magazine Blue at the time – and who would later become a close friend – spoke of the look disparagingly, saying that it was “not particularly slimming”. Elaborating in the biography of McQueen’s life, Blood Beneath the Skin by Andrew Wilson, Todd is quoted remembering the pressure the catwalk turn put the designer under: “the kid’s not long been in the spotlight, is extremely conscious of his weight, about to walk out to a room full of his critics looking like a boudin blanc, and is in the presence of his uncontested idol, Rei Kawakubo.”

Little is known of the pair’s interaction, or whether they even talked (Kawakubo speaks little English, and in her rare conversations she speaks through a translator) but that year McQueen would team up with longtime collaborator and photographer Nick Knight for the 20th edition of Visionaire magazine, guest-edited by Comme des Garçons. It remains perhaps the pair’s most memorable collaboration – the photograph of Devon Aoki in particular, where the model channels an alienesque Manga heroine, forehead sliced open, petals emerging from the scar. (The photograph would later become the cover of Knight’s monograph, Nick Knight.) Elsewhere in the series of images, Laura de Palma would wear the controversial “Bellmer” harness, akin to a large square shackle, and first worn by African American model Debra Shaw in McQueen’s S/S97 La Poupée show.

In Unseen McQueen for ShowSTUDIO, filmed to coincide with Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty at the V&A, Knight would recall the shoot as drawing upon “Japanese-isms” and the quiet power of the country’s cartoon heroines. “Fragile and frail on the outside,” Knight remembers. “But with a steel will behind that façade.” It is a dichotomy that surely defined much of McQueen’s work – and could perhaps be a fitting descriptor for Kawakubo herself, who, despite a quiet demeanour and diminuitive form, wields an undisputable power over fashion decades on.

If the editorial was something of an ode to Kawakubo, then McQueen would continue to cite her importance up until his death in 2010. “I think that every designer you ask will be influenced by Rei in one way or another but what makes them a good designer is them moving the Rei concept on for their own label,” McQueen said. “The tulle over a suit, masking a jacket over a coat, pearls trapped inside layers of fabric – moving it forward, not just taking it, digesting it and regurgitating it the same way.

"What’s really impressive about her is that she’s never backed down. I believe everyone should be like that, but it’s hard. I’ve been in this business for 20 years now and I know how tough it is to do the things you want to do.”