Grace Wales Bonner is a designer who makes clothing as intellectually astute as it is well designed. This is due in large part to her seemingly endless ability to absorb the cultural artefacts around those subjects which have informed her work the most – namely race, masculinity, identity and the dislocating effects of diaspora. Set among lavish narratives, her collections grapple with a question: what is lost and what is gained when people, and their traditions, cross borders?

If Wales Bonner chose to show her Spring/Summer 2019 collection through a series of intimate appointments in Paris rather than as part of London Fashion Week Men’s, as she has since her debut – first with the support of Fashion East, then under her own name – her impulse to weave meaning around her clothing, outside of the runway show, has not abated. This time, her initial reference point was experiential – earlier in the year, the designer attended a spiritual retreat in Goa, India, which set a new trail of thinking in motion.

As such, the collection seems to reflect the clothing one might expect to find within an Indian ashram, a space designed for spiritual exertion (ashrams are known for their focus on meditation, as well as various types of yoga, including Ashtanga, Kundalini and Asana). Where Wales Bonner has previously been lauded for her lean, finely tailored suiting, S/S19 saw new focus on casualwear, the silhouette skewing towards the loosened-up proportions of sportswear. Trousers were cut wide and airy, so too elegant shirting; nylon yoga pants and anoraks were held in place with toggle fastenings. Indian brocade, wrapped round the waist, and embroidery drawn from the evening-wear of maharajas added a sense of historical grandeur – while the vivid colour palette, which saw shades of orange and pink in a single look, might for viewers of Netflix’s Wild Wild Country have recalled the tonal uniform of fated Rajneeshpuram community, and guru Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh.

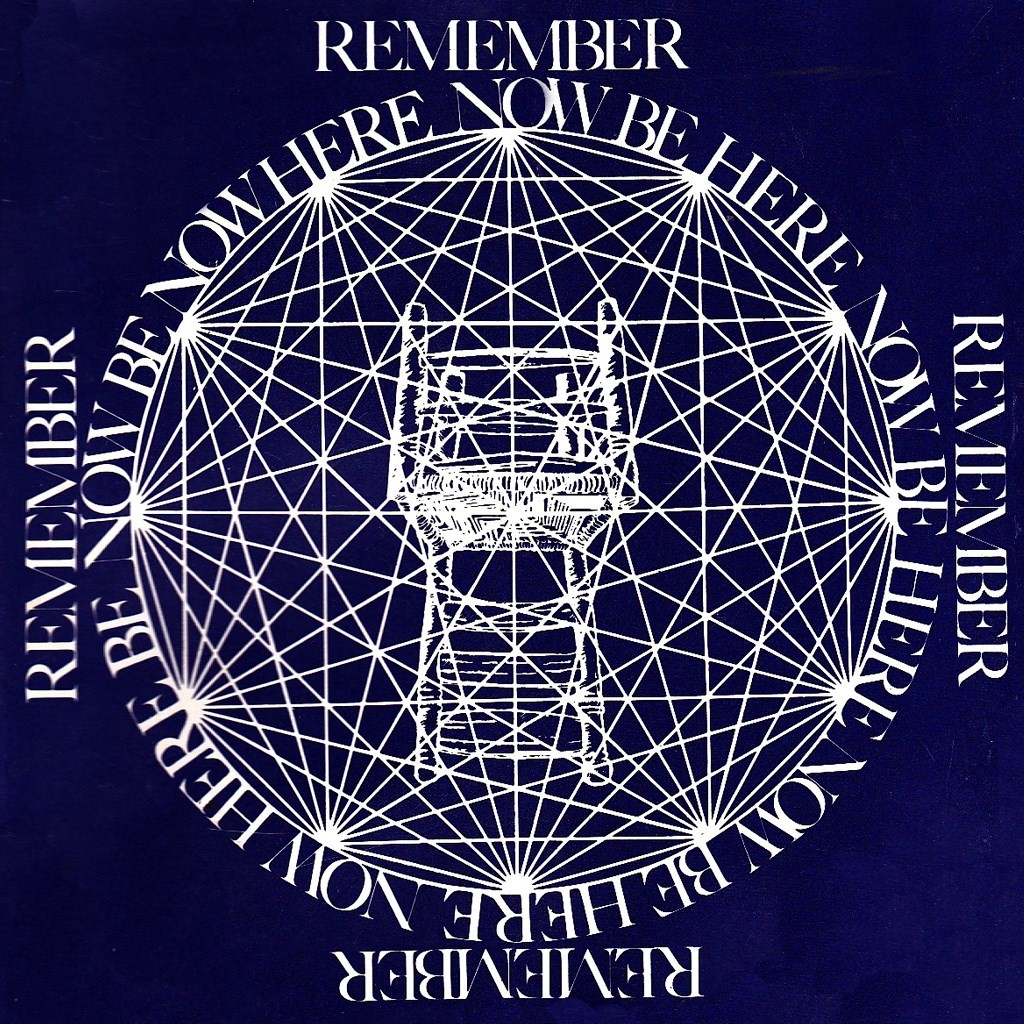

Jersey pieces were imprinted with the words of Ram Dass, the American guru – christened Richard Alpert – a man attributed with bringing eastern spiritualism to the west (yoga), in the 1970s after meeting spiritual teacher Bhagavan Das in India in 1967. Much of this was down to his tome Be Here Now; released in 1971, it was part of an early wave of bestselling spiritual self-help guides and posits a simple lesson, learnt by Dass in India after experimention with LSD, breathing exercises, meditation and Hatha yoga – to, as the title suggests, “be here now”. Being present is, for Dass, the key to spiritual enlightenment. “We’re talking about metamorphosis,” he writes. “We’re talking about going from a caterpillar to a butterfly, we’re talking about how to become a butterfly.”

The slogans – taken verbatim from the illustrations in the original publication – contain phrases like: “The stillness. The calmness. The fulfillment. When you make love and experience the ecstasy of unity.” Such instructions had been circulating in Wales Bonner’s mind for quite some time – she began reading Be Here Now aged 18, in her first year at Central Saint Martins. “The messaging felt very important for the collection, it was about exploring states of being and it is a beautiful, rhythmic and inspiring text with a universal message,” Wales Bonner told AnOther. The foundation allowed the designer to use the images, with part of the sales going towards the Love Serve Remember Foundation, where the book can be purchased. “It was a real honour to have the trust of the foundation to interpret such an influential and meaningful work,” she says.

“It was about exploring states of being and [Be Here Now] is a beautiful, rhythmic and inspiring text with a universal message” – Grace Wales Bonner

The collection, entitled Ecstatic Radical, did not take these teachings in isolation. Rather Wales Bonner was fascinated by the idea of – like Ram Dass’ own journey – what happens when eastern spiritualism comes west. “[The collection] explores devotional aesthetics, and Be Here Now is a beautiful example of this,” she says. “I was also thinking about meditative sound as an access point to a new state of consciousness. I accessed this initially through African American musicians like Alice Coltrane and Laraaji, who took me on a journey thinking about how one can interpret eastern spirituality, to then thinking about how different groups travel and interpret their environment, weaving their own histories within that of another’s.”

And Alice Coltrane – who herself, after a career as a jazz artist which began in Detroit and subsequently saw her marry fellow musician John Coltrane, began an ashram in California – was as much of a nexus of the collection as Dass in their shared beliefs regarding eastern spiritualism. Coltrane’s music, which would come to combine the devotional gospel of her youth, jazz and the traditional chants she encountered when she sought guidance under guru Swami Satchidinand, spoke of how spiritual practices from the east could be transmogrified into powerful new forms. “For, eternally, divine music shall always be the sound of peace,” Coltrane once said. “The sound of love, the sound of life, and the sound of peace.”