Five things you didn’t know about the body-fascinated School of London, who inspired this season’s menswear collections

Much like the designer himself, the Alexander McQueen man has always led a double life. What first appears to be an impeccably cut suit, informed by the designer’s apprenticeships on Savile Row, turns around and reveals sexy, fetish-informed straps; crisp white shirting may be spattered and dip-dyed, infusing a luxury garment with a violent undercurrent. It comes as little surprise then, that for her S/S19 menswear collection, creative director Sarah Burton turned her lens towards a group of artists who occupied a central position in McQueen’s prodigious and perverse imagination: the School of London.

For the most part, this loosely defined collective – with star names like Francis Bacon, Lucian Freud and Frank Auerbach – had undergone rigorous training at art schools that they later rebelled against with their bleak visions of the human body in all of its pain, pity and squalid pleasure. More importantly perhaps, they revelled in the contradictions of British identity, lavishing as much attention on the aristocrats and glitterati of their day as the petty thief, hustler or rentboy stalking the back alleys of Soho. Across five of the movement’s defining features, we examine why the London painters serve as an enduring reference point for the McQueen brand – and what it says about masculinity and menswear today.

1. As a movement, the London painters are notoriously difficult to define

The School of London, the London painters, the British Neoexpressionists: the array of names for the movement alone pays testament to its indeterminable identity. There was no manifesto and no founding date, and the period in which they were active has been suggested as extending across almost three decades, from the end of the Second World War to the early 1970s. What really ties these artists together is their social circle, with many of the same faces cropping up from painting to painting – it was an intergenerational milieu, with cross-pollination between the older establishment like Bacon, Leon Kossoff and R.B. Kitaj, and the 1960s upstarts emerging from the Royal College of Art that included names like David Hockney and Allen Jones.

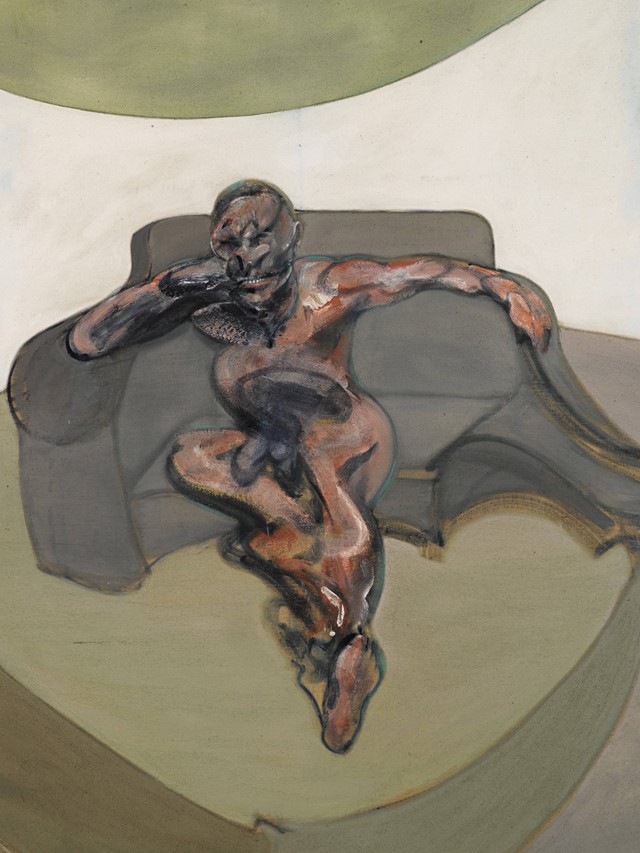

While their lives are well documented, it means that most critical writing on the movement comes with a heavy biographical slant: accounts of sordid, weekend-long binges across Soho, bacchanalian orgies in Kensington townhouses, drug-fuelled frenzies of creative output – you name it, they did it. What this overshadows is their extraordinary technical ability. Even the famously untrained Bacon, who made a splashy entrance on the London scene with his era-defining Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion in 1944 – capturing all of the horror and anxiety of post-war Britain – had an instinctive mastery of colour and composition. Despite the snobbishness that still surrounds critical understanding of his work, Bacon exists as proof that as an artist there are some skills you simply can’t teach.

2. They radically pushed back against the artistic trends of their time

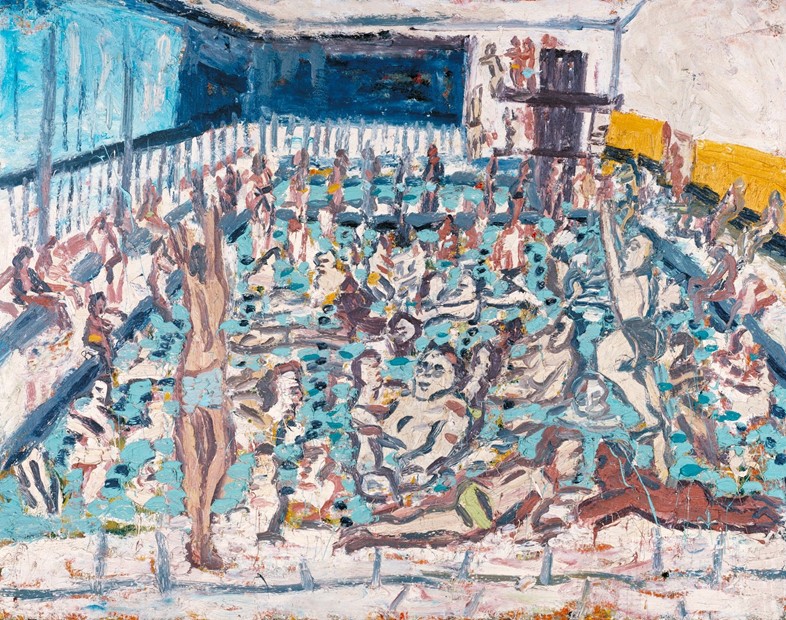

What further links this motley crew is a relentless fascination with the human figure. Where the fashionable developments taking place in America – everything from Abstract Expressionism to Pop to the conceptual art of the 1970s – emphasised either the artist’s inner emotional life or a broader critique of popular culture, the London school were always fascinated by the figures who surrounded them, an intense curiosity in the characters that populated their insular world.

That’s not to say their portraiture was conventional. Frank Auerbach, another leading voice, built up his portraits with layers of impasto so thick that they become almost sculptural, while Bacon famously worked on the unprimed rear side of the canvases he purchased to give his paintings a textural, haptic magnetism. Where their American contemporaries attempted to form a new aesthetic language that entirely did away with convention, the London painters took these traditional formats and turned them on their head. It was equally as radical in its own, quiet way.

3. Their legacy is secured by the timeless photographs of John Deakin

Across the seedy streets of Soho in the 1960s and 70s, the London painters could be found rubbing shoulders with the capital’s most colourful characters, whether during decadent, wine-soaked lunches at Langan’s Brasserie or drinking away the afternoon in the now legendary Colony Room Club. Bearing witness to this debauchery (and almost always involving himself in it) was the photographer John Deakin. His best-remembered portraits are of the towering figures like Bacon, Freud and Auerbach, but to really get under the skin of this ragtag group of painters, it’s his images of the regulars at these bars and restaurants that reveal what propelled this artistic coterie.

The imperious landlady of the Colony Room, Muriel Belcher, was immortalised not just by Deakin but in paintings now worth millions by Bacon and Michael Andrews. Described by Christopher Hitchens as the “rudest woman in Britain”, you would be wise to clarify the distinction she made between “cunt” and “cunty” — while the former was reserved for those she despised, the latter was a bizarre term of endearment. “Shut up cunty and order some more champagne,” she would screech across the bar to Bacon, usually surrounded in a corner booth by wealthy collectors, fellow artists, and a gang of East End rough trade he might be hoping to take back to his west London maisonette after closing time. It’s this patchwork of London life – high society and swindlers rubbing shoulders – that continues to pique the curiosity of artists and designers decade after decade.

4. The London painters are a recurring touchstone for McQueen

If there was an artistic precursor to Alexander McQueen’s mind-melting contortions of the human form, it would surely be the School of London. For A/W14, the house printed some of Deakin’s most iconic pictures onto garments framed by geometric patterns that recalled the scrappily developed edges of his photographs. One of his favoured subjects, the poet and Rimbaud translator Oliver Bernard, was not only superimposed onto shirts but saw handwritten lines of his poetry scrawled across shirts to become elaborate, decorative prints.

This creative camaraderie is more than just a one-off reference, however. You could read echoes of Francis Bacon’s searing visions of the abject body – wounds that leak and ooze with thickly layered paint and mouths wrenched open in silent screams – into any number of McQueen’s era-defining collections. Michelle Olley stifled by a gas mask and covered in moths in S/S01’s Voss carries could be plucked straight from one of Bacon’s early 1970s bed paintings, while Shalom Harlow’s spray paint extravaganza of S/S99’s No. 13’s closing look has a palpable air of an Auerbach portrait, layered with paint until the body fades into near insignificance. Both McQueen and the London painters might have been obsessed with their friends and familiars, but their real curiosity lay in pushing the representation of the human form to its most shocking limits.

5. They offer an interesting template for where men’s clothing could go next

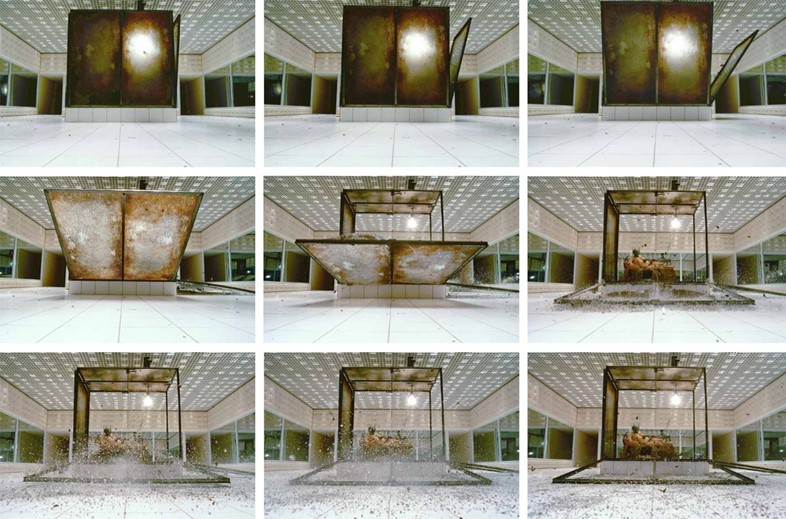

For McQueen’s S/S19 menswear collection, the degradation and squalor of the London painters’ output came refracted through the brand’s luxurious lens. The chaotic environment of Bacon’s studio was distilled into a kaleidoscopic print of colourful splodges across sharp tailoring, while the exquisite final series of looks were slick black suits with single, wide brushstrokes of paint across the breasts and lapels that dissolved from trompe l’oeil embroidery into tassels that suggested the unfinished mark-making of an invisible artist.

What made it radical, however, was its refusal to pander to the men’s wear status quo: where other storied houses have embraced the streetwear revolution with open arms, Burton understands that youthful radicalism doesn’t come solely by way of a tracksuit or a chunky sneaker. The School of London might have included some of the 20th century’s most transgressive artists, but their real subversiveness lay in taking prestigious art historical formats – in this case, portraiture – and wilfully debasing it. Perhaps a more exciting new chapter for men’s fashion could lie in a playful disruption of the conventions of luxury men’s wear rather than simply transplanting sportswear into the arena it once occupied. Watch this (paint-splattered) space.

All Too Human: Bacon, Freud and a Century of Painting Life runs at Tate Britain, London until August 27, 2018. Catwalking: Photographs by Chris Moore, with foreword by John Galliano, is out now, published by Laurence King.