Gucci’s specially created Flora print was the only thing fit for a newly anointed princess

Grace Kelly’s film career might have been brief – it lasted a scant five years and numbered just 11 films – but there was something about the directness of her presence in front of a camera which stuck. It was in the films of auteur Alfred Hitchcock that her glacial demeanour was most potent, though it would be George Seaton’s The Country Girl which delivered her first, and only, Oscar. “The Kelly effect is not unlike the James Dean effect (three great films, three bit parts), whereby a few brief hours of screen time continue unquenchably to burn,” The New Yorker critic Anthony Lane wrote of her legacy.

Of course, her lofty position in the narrative of 20th-century popular culture – one shared by perhaps the only two other women who so entirely transcended the moniker of “actress” as she, Marilyn Monroe and Audrey Hepburn – was affirmed by her marriage to Prince Rainier III of Monaco in 1960. Aged just 26 she retired from the film industry to undertake a role which was all her own – that of a former actress, and Monégasque princess. (“I’m very happy that Grace has found herself such a good part,” Hitchcock would slyly remark on the occasion of her engagement.)

As such her wardrobe, already a venerable force thanks to several well-outfitted film roles, became something of a definitive statement of how to dress as a woman of obligation. Favouring an uncluttered line, she was emphatic in her embrace of Christian Dior’s full-skirted, pinched-waist New Look which provided the silhouette for both tailoring and gowns (though not all were created by Dior himself). It was a tasteful, restrained brand of femininity, accented by classic accessories and continues to set a precedent for other such women of status – the Duchess of Cambridge’s modest, lace-covered Alexander McQueen wedding gown likely found its forebear in Kelly’s own, a gift from her studio Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and its costume designer Helen Rose.

Her fashion legacy, though, can be reduced to a handbag – the Hermés Kelly – symbolic of the restrained affluence of the actress’ own wardrobe. High-handled, trapezium-shaped, the oft-imitated bag, which began life as a storage solution (in a larger size) for a horse’s saddle, was introduced to Kelly by Hitchcock’s wardrobe designer Edith Head. Head was given free rein by the director to purchase Hermés accessories for the film To Catch a Thief, in which Kelly starred. The actress was duly enamoured by what would become the Kelly – though it was not until 1956 when she gave it the ultimate approval, using the bag to shield her face from the lightbulbs of the paparazzi just hours after her engagement was announced.

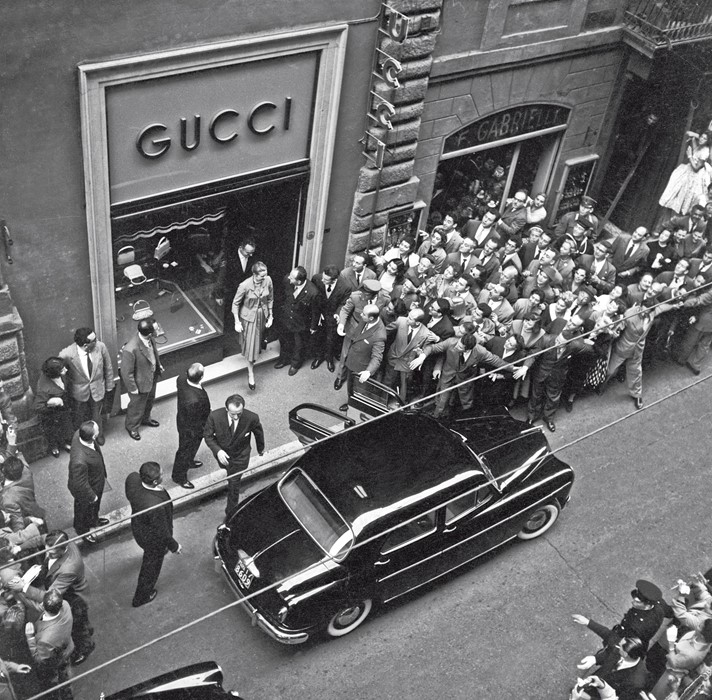

In 1960, four years after her marriage, Princess Grace would visit Gucci’s flagship store in Milan. It was something of a golden age for the Italian house, who was now well-versed in outfitting the international jet-set – it had recently opened stores in Beverly Hills and Palm Beach, and moved its New York store on to Fifth Avenue opposite the St. Regis hotel. (Unfortunately, it would not last long – in the 1970s the family dissolved into infighting, before Gucci was resurrected by designer Tom Ford in the 1990s.) While shopping, Kelly would select one of Gucci’s signature bamboo-handled bags. Rodolfo Gucci, son of Guccio Gucci, the founder, wished to present her with a gift to go alongside the purchase – yet nothing seemed quite befitting for a woman of her considerable renown.

And so, the Flora print was born. Commissioning Italian illustrator Vittorio Accornero, Gucci asked for a design for a silk scarf as elegant as she (Kelly’s love of florals, and silk scarves, was confirmed at that year’s Olympics where they became a uniform of sorts). The result was a print containing 43 varieties of flowers, plants and insects in a design which encompassed over 37 different colours, which was no mean feat – each scarf was painted entirely by hand. Accornero found inspiration in Botticelli’s Allegory of Spring, which depicts the nymph Chloris reborn as Flora (Spring) in a gown imprinted with poppies, roses, violets, daisies and chrysanthemums.

It is a print which has endured – in Florence’s Gucci Garden, the immersive museum opened last year by current creative director Alessandro Michele, a room is dedicated to the house’s iterations of flora and fauna, which have spawned numerous items of clothing and a series of fragrances. Of the house’s contemporary designers Michele has embraced Gucci’s botanic past the most wholeheartedly; floral motifs are found across his collections – his A/W18 collection, for example, opened with a blouse imprinted with his version of the Flora design – and his first collection of fragrances for Gucci is entitled Bloom, heady with floral notes.

In fact, the Gucci Garden is not only the given name of the Florentine museum (which also houses a store and restaurant) but also a statement of how Michele defines his Gucci “pluriverse”. “The garden is real, but it belongs above all in the mind, populated by plants and animals,” Michele says. “Like the snake, which slips in everywhere, and in a sense, symbolises a perpetual beginning and a perpetual return.”

Gucci Garden is open now in Florence’s Piazza della Signoria.