Decorated by the work of François Boucher, Westwood’s 1990 corset clashed prurient traditional dress with provocative sexuality, writes Alexander Fury

“Some years ago I wanted to do a collection where I would try to put together a range of fabrics so rich in scope that it would live up to all the different qualities and richness of texture seen in oil paintings. From linen, to lace; tweeds to velvet.

“When I arranged these fabrics, there was still something missing: somehow, the paintings themselves. I included a piece of painter’s canvas; and then I knew I just had to have a photographic print of a painting. I chose the most decorative painter – Boucher – and the most typical Boucher painting in the Wallace is for me the Shepherd Watching a Sleeping Shepherdess. I just love the ribbon tied in a bow around the sheep’s neck… I wanted her to look as if she’d just stepped out of a painting.

“I called the collection my ‘Portrait’ collection.” – Vivienne Westwood, 1996

Sometimes, fashion is fascinating because it is a mirror of its time; sometimes, it is because it is a wide-flung window, a painted ceiling, a great escape. In the wake of Black Monday and the financial crash of 1987, Vivienne Westwood unleashed a number of collections inspired by Baroque art, underlined by ancient Greek and Roman themes and exuberantly sensuous. While other designers pulled away, rinsing collections of colour and extraneous detail in the birth of an approach to be known as minimalism, or evoking distress and intentional wear and tear which would be dubbed first deconstruction and, later, grunge, Westwood pushed in the opposite direction. She continues to decry orthodoxy as “the grave of intelligence” (to quote Bertrand Russell) and likewise bucks against convention.

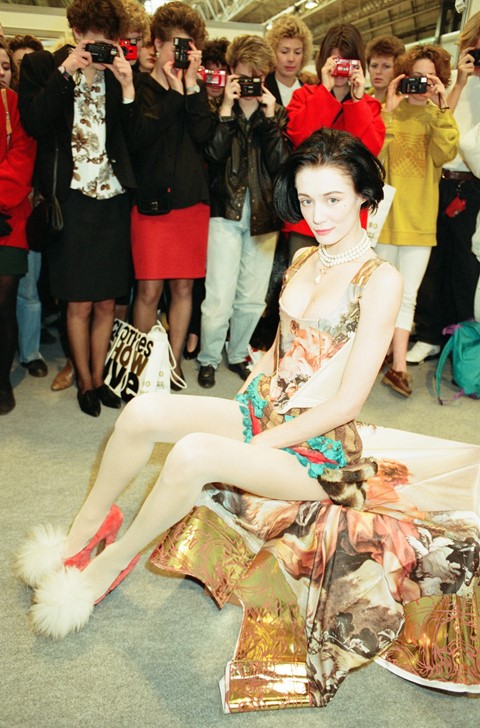

Which is how, in March 1990, under the gilded ceilings and Regency chandeliers of the Institute of Directors and under the cloud of an ongoing worldwide recession, Westwood unveiled a collection she called Portrait. It was inspired by the grandeur of 18th-century oil painting, shown in a room surrounded by some of the Crown Estate’s finest examples. In the face of crashed markets and crunched credit, its luxury was near-ludicrous, almost obscene. It caused a sensation.

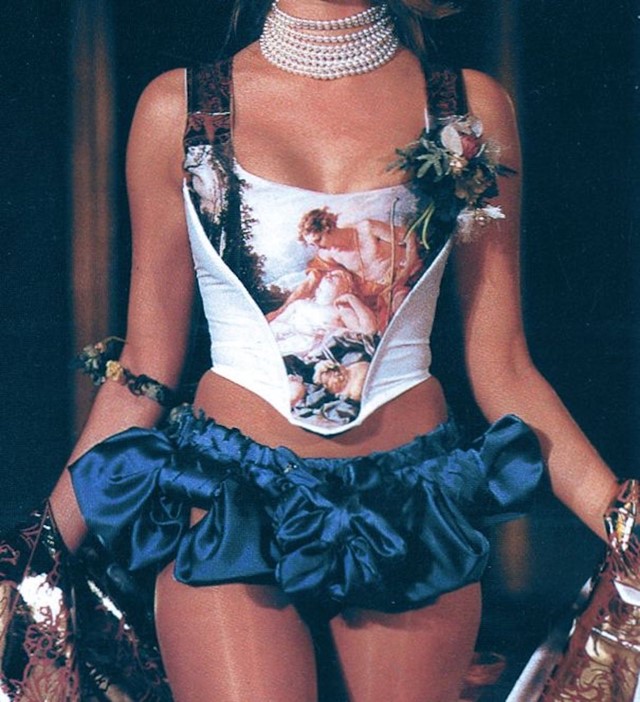

A centrepiece of that handsome show, this corset, bearing a photographic print of a chocolate-box image by the Rococo painter François Boucher (1703-1770), has become an archetypal example of high Westwood style. It appeared in subsequent collections as was, or sometimes with different artists’ work (a chortling baby by Franz Hals; a swarm of Fragonard cherubs; a Nicholas Hilliard of Elizabeth I), a swag of gilded frame across the shoulders like a masterpiece literally torn down and broken up across the body. This first example was drawn from the Wallace Collection, a national treasure and source of constant inspiration to Westwood throughout her career. An array of paintings and decorative arts of the French ancien régime assembled in the 19th century, many bought in biens nationaux – revolutionary sales of the confiscated goods of aristocrats – the Wallace Collection is located in London on Manchester Square, in the former townhouse of the Seymour family, Marquesses of Hertford. (The collection was amassed by the first four Marquesses and Sir Richard Wallace, the son of the fourth Marquess.) Alongside braces of Sèvres porcelain and ranks of brass and tortoiseshell furniture by André-Charles Boulle, cabinetmaker to Louis XIV, the Wallace includes no less than 19 works by Boucher. This one is Daphnis and Chloe – also known as Shepherd Watching a Sleeping Shepherdess, or less expressively as inventory number P385 in the Wallace – painted in 1743-5. To Westwood’s eye it is stereotype Boucher, a study of lustrous, satiné flesh and swagged fabric and faux-rustic eroticism. Boucher was incidentally the favoured painter of Madame de Pompadour, King Louis XV’s mistress.

Westwood also decorated corsets in this collection with Boulle’s marquetry ormolu and prancing mythological beasts, pulled from the reverse of a toilet mirror made for the Duchesse de Berry, daughter of Philippe duc d’Orléans in 1713, and executed in gold-foil prints across richly coloured velvets. But was the Boucher-patterned variant that captured the popular imagination, perhaps because of its blatant voluptuousness, and unapologetic corporeality.

Vivienne Westwood’s Boucher corset is not just a collectible totem of a landmark collection. It summarises a philosophical approach that has produced Westwood’s very best work – colliding historical reference with contemporary culture, prurient traditional dress with provocative sexuality. The corset was first revived by Westwood in 1987, named by her the ‘Stature of Liberty’ because of its effect on the posture. Its conical shape, rounded front and heaving embonpoint spilling slightly over a low-cut décolletage are all reminiscent of the 1700; its shape directly derived from original 18th-century stays. The style was updated physically, with the addition of lycra sides and a zip up the back; and ideologically, in that it was worn as outerwear, often with very little else. What was once a symbol of patriarchal control over women’s bodies became a third-wave feminist symbol of a re-embracing and recontextualising of previously eschewed overt female sexuality. A liberated stature, indeed.