Moments of dignity and grace in fashion are few and far between. If burgeoning collections high and low, imagery aimed at not just the insider few but many, and voracious social-media activity are all evidence of a new kind of democracy, the speed at which everything now moves may be counterintuitive to these. The world of Yohji Yamamoto is, by contrast, their very embodiment.

There was his 1981 Paris debut, of course. Stripped of all sound but an amplified heartbeat and peopled with pale-faced models wearing oversized black shapes peppered with holes, the show’s impact was seismic. That is perhaps why it was dubbed by some, clearly struggling to comprehend and with quite astounding insensitivity, “Hiroshima chic”. Other more enlightened editors hailed Yamamoto’s entrance onto the international stage as a grand new dawn. It was only a matter of two or three seasons before they were proved right. The designer’s aesthetic of loose layers wrapping the body, flat shoes and a dominance of black became a genuine alternative to the fraught, highly wrought clothes that otherwise characterised the 1980s. Yamamoto’s was another way.

Later, Yamamoto’s Spring/Summer 1995 women’s collection, the first to pay open tribute to the shibori technique of his native Japan, albeit with traditional silks mixed with innovative rayons, provoked a near-rhapsodic response. It is well known that Japanese (and also, incidentally, Belgian) designers prefer not to be pigeonholed according to their nationality. And that is understandable. Despite, or more likely because of, that there was a tenderness to this open ode to the country in which the designer was born and still lives that moved.

Yamamoto’s clothes often affect his audiences profoundly – unforgettably. His Spring/Summer 1999 collection, Brides & Widows, saw rebel Yamamoto look at the moments in a woman’s life when, however anti-establishment she might pride herself on being, she has an eye on convention. Intricately choreographed – part classical Japanese theatre, part unashamedly romantic western ceremony – it was among his most loved (and loving) creative outpourings. Suffice it to say it brought the audience not just to its feet but to tears. “To wear a wedding dress,” the designer told me a few days afterwards, on one of several occasions we have met over the years, “means at least a kind of success, the unification and combination of men and women. That is what’s called happiness.” And the widow part of the equation? “You wouldn’t become a widow if you didn’t marry.” Yamamoto’s predominantly elliptical words aside – and the apparently effortless passage from oblique to plain blunt that entails – the beauty and even majesty of this performance was unprecedented. Yamamoto is credited frequently and consistently with the gift of evoking rarely felt emotion through his work. The designer feels deeply; we feel it, too.

For Autumn/Winter 2018, and in a still more openly elegiac mood, the invitation to Yamamoto’s show – it took place as always on the Friday evening of the Paris ready-to-wear season – was a photograph of a female nude accompanied by the words: “Hommage. 1. M Cubisme. 2. Mon cher Azzedine.” The work of Pablo Picasso had inspired Yamamoto, whose approach to design is similarly sculptural: skewed. This was also an homage – Yamamoto used the French spelling – to Azzedine Alaïa, a contemporary and friend, who had died on 18 November 2017, so less than six months before. To mix an elevated cultural reference with something so private was ambitious, to say the least. Here was an audacious, noble and highly charged fusion of the intellectual and the personal, of the mind and the heart. In pride of place, front row, was Alaïa’s extended family, those he spent every day and evening with throughout much of his career. His partner, the artist Christoph von Weyhe was there; his studio director and right-hand woman, Caroline Fabre-Bazin, who also worked with Yamamoto from 1985 to 2003, sat beside him.

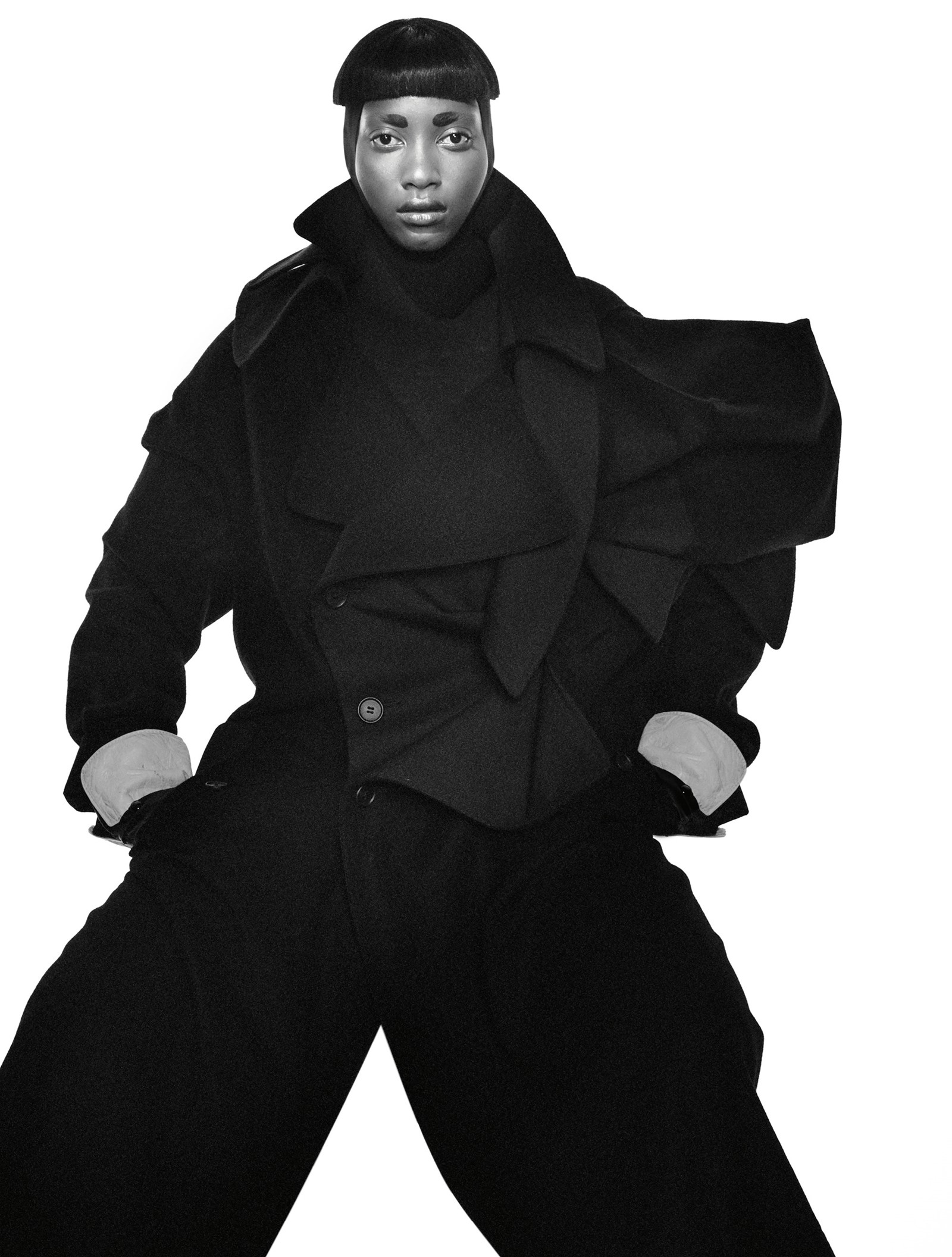

The soundtrack, written by Yamamoto and also performed by him – famously, Yohji plays guitar – was haunting in its own right: “Can you think of me? I think of you always. Winter is very cold. Where are you? Where are you?” Yamamoto is not a major advertiser, his shows are long and late and therefore not as well attended as might be expected, given his reputation in the industry. But the clothes, as always, were magnificent. Both elegant and unexpected, each piece was its own lesson in pattern-cutting, heavy with sentiment but feather-light to the touch. And here also were the most heartfelt allusions to M. Alaïa, another master couturier – another of the last – with whom Yamamoto clearly identified and whose loss he felt sharply. Rather than the sloppy copies proffered by lesser talents, the Alaïa-isms here were a pure paean from one master to another, filtered through Yamamoto’s distinct aesthetic prism. There were boots with scalloped edges, perfectly fitted double-breasted coats, supple leather corsetry curving around Yamamoto’s signature and beloved black gabardine. At the end of the show, Yamamoto came out and bowed directly to Alaïa’s nearest and dearest before greeting them personally backstage.

“I was thinking about Azzedine and about Cubism,” he said, just after. “How do those things work together? Azzedine suddenly disappeared, he passed away. Normally I have some thoughts, make fittings and cuttings, and gradually the theme comes. This time the theme was decided. And then it was very hard to achieve it.”

“Are you happy?” I asked him, possibly rushing in where angels fear to tread.

“Fuck,” Yamamoto replied with a broad smile.

This kind of curve ball is typical of the designer. Happiness is not something that he vocalises as much as he does anger, although even in the case of the latter there is a gentleness to him, not to mention a wicked sense of humour, that belies any inner rage.

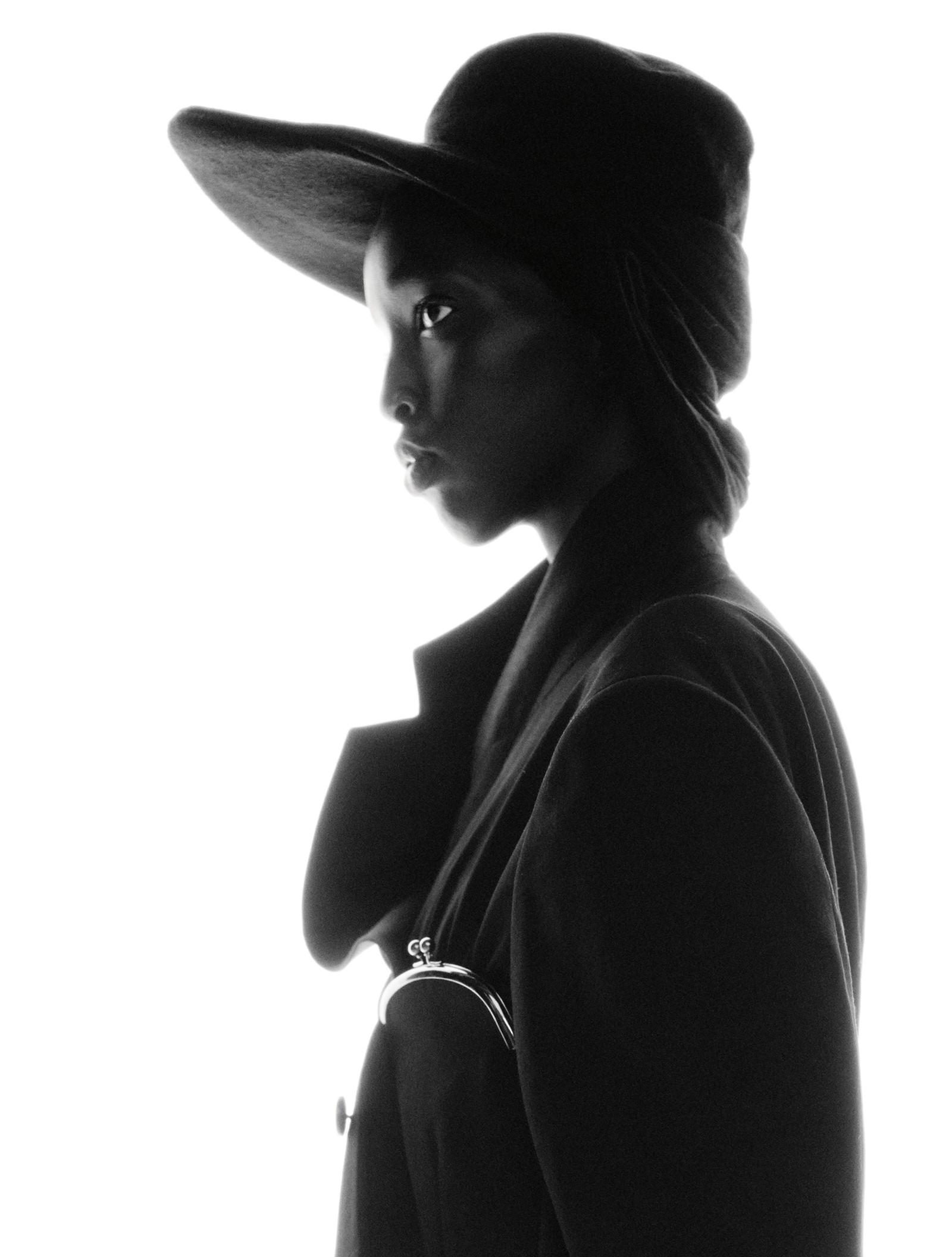

We first meet for this interview the day after his menswear show, in Paris, in January. Yamamoto speaks openly about his sadness. He is dressed in his habitual black, with the fedora that has become a signature (he doffs it to his audience, courteously, at the end of each show). His handsome face is heavily lined: he turns 75 this October. Sitting in the warm, light-filled garret of his showroom of many years in the rue Saint-Martin, with its low ceilings and heavy, raw wooden beams, he says: “I am a dressmaker who has been doing almost the same thing for more than 40 years. I used to be anti-fashion. I used to be anti-trend. But we are losing very important designers, year by year. From my side, I’m losing my competitors. Azzedine. Alexander McQueen. I feel like I’m lost. I feel like I’m losing the people who I can punch against. You understand?”

The fine line between fighting against, and passion towards, the designer’s chosen métier is succinctly expressed here, and that was indeed central to the natures of both Alaïa and McQueen.

At surface level, the oversized silhouette that this designer favours, which envelops the female form over and above exposing it, couldn’t be more at odds with the figure-hugging line that Alaïa was best known for. Yet the similarities between the two men outweigh the differences. They met in 1987 and were friends over the years that followed. Their use of black, a shade that focuses attention on cut and proportion; their fascination with fabrication and craft; their insistence on the importance of the first-hand input of the designer, of the touch of his or her hand, from the start to the finish of each and every garment; the understanding of haute couture from Christian Dior to Mme Grès, from Balenciaga to Vionnet; and their steadfast refusal to kowtow to the whims, ephemera and manners of the fashion establishment unites them. Above all, Azzedine Alaïa loved and served women and Yohji Yamamoto continues to do so. If anything motivates this somewhat reticent figure to carry on creating, it is surely this.

“I was lucky enough to see Yohji’s first show in Paris in 1981 and my world really changed,” Fabre-Bazin says. “I was studying at business school and, when I saw that, I realised I wanted to work in fashion. It wasn’t just the clothes. It was the emotion, the nostalgia, melancholy, romanticism, dignity. I was so touched. Then, in 1985, I was on a trip to Japan and a friend of Yohji’s said to me, ‘If you want I can take you in at Y’s, the Yohji group.’ There was no real salary but I said, ‘OK, I want to start.’ I learnt from Yohji to be patient and conscious of the fact that nothing lasts. That is something very strong in Japanese culture and in Buddhist culture – to see things as they are but to be conscious that nothing lasts forever. You know, even the blossom trees.

“When Yohji told me that he wanted to pay homage to M. Alaïa – I saw him several months before the show – I was super-moved. It was one of the most beautiful moments. Yohji and M. Alaïa used history in fashion, history in pattern, history in technique, to build the future. Over the years I also understood how close they were in the way they considered women. They really loved and respected women. For them, a woman will never feel vulgar or disguised. Both of them wanted to protect women. M. Alaïa always said that he wanted women to feel confident, to feel proud, to feel brave in their clothes. And Yohji wants to give them shelter in clothes. I always say that they are touching the stars while having their feet firmly on the ground.”

It is true that there is a romance and a reverie that has long informed the work of Yamamoto, who is, in certain ways, removed from earthly matters – consciously so. On the other hand, his aesthetic and the sources of his inspiration are grounded in reality and in his own background, too, which provides considerable insight into his milieu. While applying biographical analysis is not necessarily key to understanding a person and their work, with Yamamoto it feels obstructive to separate the two. Even the Yohji Yamamoto label is arguably autobiographical – it is the designer’s signature, although, as is so often the case with fledgling designers, the reason behind that is pragmatic as well.

“I was thinking that the role of a fashion designer is to stay backstage,” Yamamoto says. “At that moment when I started, haute couture designers, they never came out, and I liked that. I liked that very much. I like being behind. So when I created my ready-to-wear company, I called it Y’s, as in Yohji’s. At the same time we had a great designer – Yves Saint Laurent. And it was so nice when my manager negotiated with Yves Saint Laurent’s manager, who said, ‘You can use it, you can use Y’s, apart from when you do the fashion show. Then please don’t use Y’s.’ So I was still working on the first Paris collection in Tokyo. There was a phone call. ‘Mr Yamamoto, you have to write your signature as soon as possible and send it to me. For the label.’ So I finally agreed and wrote Yohji Yamamoto. At the beginning, people couldn’t even pronounce Yohji. ‘Yogi? How do you pronounce it?’”

Yohji Yamamoto – more often today simply Yohji, as we all now know very well how to pronounce his name – was born in Shinjuku Prefecture, Tokyo, in 1943. His father was drafted and killed in the second world war. “While I was an infant he was conscripted and served,” Yamamoto writes in My Dear Bomb, published in 2010, “and his remains were never returned to us. Buried in his empty grave is the Leica camera he so adored.”

“It’s very strange,” he says now. “Until recently, I didn’t think about my father because I have no memory of him. He was sent to war when I was a one-month-old baby. I didn’t know anything about him. I just saw his photo. Ah. Good-looking man. Is it my father? I don’t know. I’m not sure. So I grew up looking at the back of my mother, hard-working, like this.” He gestures crouching down and sewing. His mother ran a dressmaking business. She made huge sacrifices to send her son to school and then university – he completed a law degree at Keio University in 1966 – and he worked for her in his free time. Fumi Yamamoto is now 103 years old.

“Four or five years ago, I started thinking about my father,” Yamamoto continues. “I don’t know why. Maybe I was thinking about my own end. It’s very natural. So when I started thinking about how to end – how can I finish, do you suffer when you die? – I suddenly started thinking about my father. He was only 36 years old when he went to the army, just one year before the war ended. He was sent to the south. At that moment, in the Japanese army, there were no big boats. So they used fishing boats. How must my father have felt, treated like that, this 36-year-old man? My mother’s friend, who luckily came back from the war, he told my mother, ‘Fumi-san, there were so many ships sinking, it was like a joke.’ A terrible joke. So I was thinking about my mother, and my father. And plus, recently, about three or four years ago, my business became crazy. And I thought, maybe this is my father, my father is pushing me.”

Despite critical acclaim, Yohji Yamamoto, the company, has struggled in recent history. In October 2009, following the 2008 financial crisis, it was rescued from bankruptcy at the 11th hour by the Japanese private-equity fund Integral Corporation, which has since re-partnered and restructured the business. By 2010, it was out of debt. The designer has since referred to these financial difficulties as “the accident”; the overriding impression is that it was just that. “I’ve had my company for over 30 years but I consider myself to be a designer first,” Yamamoto told Women’s Wear Daily at the time. “I think one reason the company has come to this is that I left too much to others. I was told about the positive things but many of the bad things didn’t reach my ears.” There is – and always has been – a sense that those who work for Yamamoto go to great lengths to protect him, on this occasion possibly to his detriment. In their defence, Yamamoto himself has never been primarily driven by commercial concerns. “I did lose ownership,” he writes in My Dear Bomb. “But on the other hand I feel like I’ve been relieved of a heavy burden. There won’t be any family battles over money issues involving the inheritance or the stock ... I consider this to be the turning point of my final chapter.”

Said chapter decrees that, today, in his native Tokyo and in Paris, Beijing and Shanghai, Yamamoto is a star, albeit a reluctant one, regularly stopped in the street and photographed or asked for his autograph. He agrees as good manners – his are nothing less than impeccable – command, but, “Really I’m shouting, ‘Leave me alone,’” he once told me. “Basically, I am a very angry man, so I generally always make an effort to be nice, to be gentle in front of other people,” he says now.

It’s not difficult to understand why the power of Yamamoto continues to resonate. The delicacy, strength, emotion and purity of his point of view is nothing if not testimony to the fact that if you believe in what you do and resist compromise, greatness prevails. “I didn’t change at all,” he says. “The customer’s mind changed, I feel. So many young people started appreciating my work, started wearing my clothes. That’s scary. A scary responsibility. By the end of December last year, the spring collection had sold out.”

“But that’s great,” I interject.

“Not great,” Yamamoto replies. “What can I do next? Scary. I have to do it again.”

In an Instagram-perfect world, there is a humanity to Yamamoto’s work that is hugely appealing, even soothing. Yamamoto is interested in asymmetry, finding beauty in imperfection rather than high-shine glamour. In his native Japan, wabi-sabi is a worldview that represents an acceptance of transience, celebrating the imperfect, impermanent and incomplete. It is safe to assume that Yamamoto has been deeply affected by such a way of thinking. “I think perfection is ugly,” he has said. “Somewhere in the things humans make, I want to see the scars, failure, disorder, distortion. If I can feel those things in work by others, then I like them. Perfection is a kind of order, like overall harmony, and so on. These are things someone forces onto something. A free human doesn’t desire such things.”

“Yohji’s first Paris show, on the rue du Cygne, was an emotional moment,” says Carla Sozzani. The former fashion editor at Vogue Italia and editor of Italian Elle often included Yohji Yamamoto in editorials and later, having opened the world-renowned Galleria Carla Sozzani in 1990, and store 10 Corso Como the following year, bought his collections. In 2002 she edited the seminal Yohji Yamamoto tome Talking to Myself. Sozzani was among Alaïa’s great friends and collaborators also. “I remember running to buy Yohji’s clothes. Later, when I travelled, his stores became destinations for me, places where I knew I would find and always buy a wonderful piece of Yamamoto. I think the people who wear Yohji recognise and appreciate an intellectual yet simple and subdued attitude. You see it in their presence. Whether it is the clothes that give the confidence or one has to have confidence to wear the clothes is an interesting question. Yohji is a gentle, open man, but also a revolutionary. You can feel his love and respect for the people around him but he needs to be free. His freedom makes him a pioneer. His effect on fashion has been huge.

“I recall a conversation between Yamamoto and Alaïa in 2005: the two spoke about everything. When it came to elegance, Yohji said, ‘Show something simple, like a shirt, and make sure that it’s different from the others.’ He also said, ‘I prefer to show the hidden body. I’m a man but I think that what is on the inside is sexiest. I don’t like to show the body ostentatiously. I prefer to dream.’”

After graduating with a further degree, this time in fashion in 1969, Yamamoto set up on his own. “I grumbled silently to myself,” he writes in My Dear Bomb, “about the impossibility of reproducing the magazine look. I hated it. Intensifying my annoyance was the fact that the shop [his mother’s] was in the Kabukicho area of Shinjuku, a place overflowing with women whose job it was to titillate male customers. They had shaped my image of womanhood since childhood and I was therefore determined at all costs to avoid creating the cute, doll-like women that some men so adore.”

Instead, he was inspired by Japanese workwear (for men) and the photography of August Sander. “When I began to make clothing, my single thought was to have women wear what was thought of as men’s clothing. In those days, Japanese women wore, as a matter of course, imported feminine clothing and I simply detested that fact.” His mother’s wardrobe also informed his aesthetic. “She wore nothing but black mourning clothes and I would watch as the hem of her skirt fluttered.”

“When I started my career,” he says, “there were so many strong fashion designers. Like Mr Kenzo, Yves Saint Laurent, Jean-Charles de Castelbajac, Sonia Rykiel. I was looking up. Maybe I can never come to such a high level. Mostly impossible, I felt. I felt like a nobody, like a nothing. So finally I chose my way of not being a great designer in the general way that is understood. I preferred to start working on the sidewalk of fashion as opposed to the mainstream, on the dark side, the wild side of the street, from the narrow, wrong side of the street.” That may have been the intention but, with Rei Kawakubo of Comme des Garçons, who debuted in Paris that same 1981 season, Yamamoto changed the face of fashion: their clothes were dark, deliberately aged, their shoes paper-soled pumps, rustic. Given the hegemony of the jolie madame aesthetic, of highly tailored, tightly fitted and flounced clothes that predominated in Paris fashion, this was indeed nothing short of a revolution. It was also a sound kick in the teeth to preconceived notions of status in designer fashion. It wasn’t long, though, before some of the most powerful people in the world – and powerful creative people in particular – looked to her for an intelligent alternative to bourgeois dress. Ironically – brilliantly – Yohji Yamamoto became the status label to see and be seen in.

Still, “When I first started in fashion, when I first started showing in Paris, I got 70 per cent booing and 30 per cent welcome,” Yamamoto says. That 30 per cent upheld a similarly unconventional and individualistic point of view to the designer himself and has remained loyal to him for decades. The actress Charlotte Rampling has known Yamamoto and worn his clothes consistently for 25 years.

“Yohji had a different way of seeing the female figure, a different way of seeing fashion,” she says. “It’s not fashion for him but a way of life, a particular way of moving in the world. I’ve always favoured the low profile of fine work and not the commerciality of it. With Yohji, he had an extraordinarily low profile, even though the look was anything but. I wanted to find something that dressed me without my actually being overdressed, ostentatious. It seemed that, more and more, I picked up different pieces of Yohji and learnt how to wear them, how to live with them, how to tame them, really. Some were quite outrageous, not in a flashy, showy way, but structurally. I would think, ‘Can I really get my body into that?’ And I found that really interesting. So I became a kind of Yohji addict. I have all his clothes from way back and still buy his clothes. It doesn’t look like I’m a disciple. It looks like me.”

Both Rampling and another great fashion designer, and Yamamoto’s contemporary, Vivienne Westwood, nailed their colours to the mast when, for the Autumn/Winter 1998 season, they modelled in his menswear show. “If you’re a good designer, you appreciate and love the work of another good designer, because they do something you don’t do and that’s what you really like about it,” says Westwood, who rarely speaks so highly of others in her profession. “Yohji’s work is a look and a big idea. I love Yohji.”

Of course, the shock of the new soon filtered into the broader consciousness. And it wasn’t just the look of Yamamoto’s fashion but the way in which it was marketed that introduced an entire new way of thinking and seeing. Marc Ascoli worked with Yohji Yamamoto from 1983 to 1987 and then again from 1995 to the early 2000s, commissioning his seasonal catalogues using both established names and the emerging talent of the time. The roster is quite something: photographers Nick Knight, Paolo Roversi, Craig McDean and David Sims all contributed, as did Peter Saville, responsible for graphic design. The result of these collaborations was every bit as groundbreaking as the clothes.

“I first saw his collection in Paris in 1982, I was quite young,” Ascoli says. “I found it totally revolutionary. It was an intellectual, sophisticated and sensitive interpretation of fashion. It was a reflection on life, not just clothes. I found that exceptional – completely original and very couture. For me it was a new form of couture – the drape, the folds. I met Yohji, and he was exactly how I imagined he would be, very open, very cool. After about half an hour he said, ‘Do you want to come to Japan?’ Imagine going to Japan in 1983. For me, it was a dream. When I arrived there, I found a family. I had never seen that before, that way of being. Everything revolved around him, his mother, a group of people that was devoted to him. It was very far from what I had experienced in Paris. There was a synergy between us, I think, but we did what he wanted. He decided everything. He had a kind of freedom and he gave us the means to do things. He was an intuitive man. I didn’t work to any image policy. Yohji didn’t care about the pedigree of the people I chose to work with. When you see images from that period, you sense that there was not the same amount of interference as there is today, that they didn’t have to shout so loudly, to speak to Dubai, to London. Today, you speak to the whole world, to everyone at the same time, and you don’t always work hand in hand with a designer.

“Right from the start, Yohji had a sense of luxury, although he didn’t use the same tools. His tools spoke of nonchalance, ruin and decadence in clothing. When you look at Yohji’s clothes now you see they are ‘pieces’ that you can keep for years. There is so much work in their construction. He works on basics, on a military jacket, on a trench coat, and he transforms them into Yohji Yamamoto for the everyday. There is an urbanity to his clothes that is very relevant. Yohji is someone who has a real sense of clothes and also a real sense of poetry. There is this feeling of a reflection on a certain kind of creativity, a kind of creativity that is at risk of disappearing.”

“I started working with Yohji in 1985, when Marc Ascoli invited me to shoot the catalogue,” Paolo Roversi says. He did so that same year, and further campaigns in 1996 and 1997. “It was a different world then. We were so free. Working with Yohji broadened my horizons. He’s special, you know. He was new, different. It was about elegance, a new elegance and about mystery. Mysterious. That’s a nice word for him. The shape was new, the proportion was completely new, the woman was new. For me, Yohji is a poet. I always went to his shows. Every show was so inspiring, so moving. Yohji loves women and you feel that, you feel his love for a woman very strongly in his work. I was always very touched by the fact that his mother was there during the show, touched by his love for and faith in his mother. His mother was more important than everything, and even if it was five in the morning and he was working on a collection, the words of his mother were more important than anything else.”

“It’s hard to describe how different it was to see somebody dressed completely in black and how it felt slightly menacing, sinister,” says Nick Knight, who photographed Yamamoto’s collections between 1986 and 1990. “Black as a colour, as a shade, whatever you want to call it, is quite a powerful presence. Also the proportions, the very, very long coats, super-long silhouettes and exaggerated sizing, all those things were so totally new. Nobody was doing them. Up until that point, fashion hadn’t really appealed to me. I felt that women were vulgarised and cheapened by fashion. It was cheap. The only reason to have the clothes was to show off your bust, your waist, your bum, your shoulders. It was all about showing off parts of your body and that wasn’t relevant to me at all. With Yohji it felt very much as if here was somebody talking about women in a way that I believed, and also wanted to. It wasn’t about showing off their figures or turning women into cardboard cut-outs of themselves. It was about their soul, about their poetry, about their heart, about them as people. It was an intellectual view of women, as opposed to a purely sexual view.”

The resulting images, among them, Susie [Bick, now Cave] Smoking (in black), Naomi [Campbell] Dancing (in kimono red), continue to find their way onto other fashion creatives’ mood boards more than 20 years after they were first seen.

“Yohji was always smiling and so sweet as a man, a pleasure to work for,” Naomi Campbell says. “I loved the clothes. We all – every model – had individual dresses, and it was very precise how you had to put them on. Back then I was like, ‘I would never be able to put this on by myself.’ I think I might be able to now. There’s a quality to it, to the way it lies, the craftsmanship is so exquisite, so perfect. The clothes are so intricate and yet simple, too, somehow – just unique. I remember jumping over and over, twirling the coat for Nick when we shot the campaign in Paris. It was a delight. I was a black model working with Nick Knight doing Yohji Yamamoto advertising in the 1980s and that was a big deal. I have really good memories of working with Yohji. I saw him in Tokyo a few years ago and it was really lovely – the same lovely, warm smile as always.”

“Marc Ascoli and Nick Knight were in charge,” Susie Cave remembers. “I was just there as a model. Susie Smoking was in no way arranged, rather it was a fleeting and unselfconscious moment, where I lit a much-needed cigarette and Nick took the photograph. But the atmosphere was palpable. We were deep in the zone. That happens sometimes with great photographers. You just lose yourself to their genius. But it was not difficult to find that moment when I was dressed in the most beautiful Yohji Yamamoto clothes.”

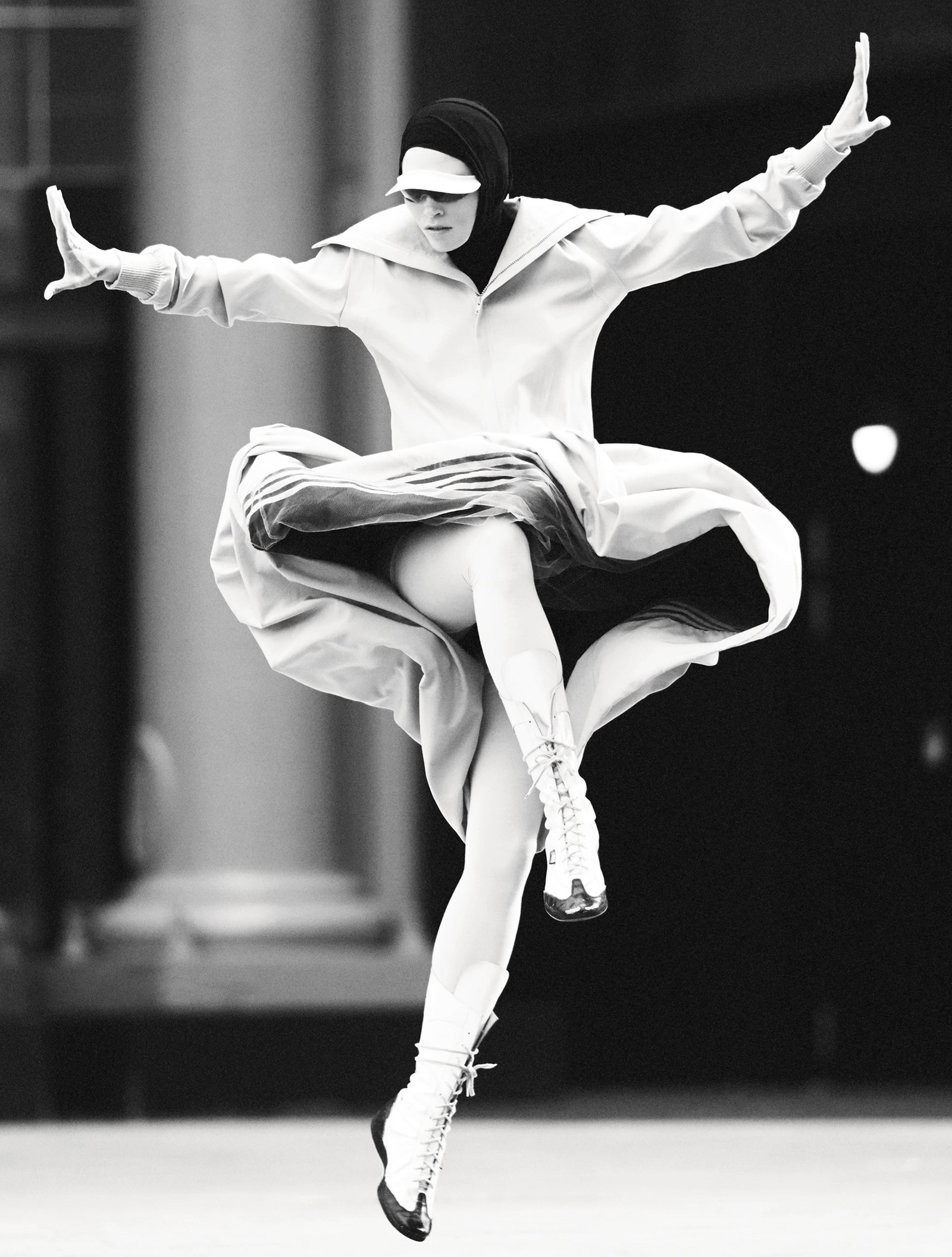

“Fashion communications culture, which we entirely take for granted now and, in fact, increasingly over the past 20 years, was relatively non-existent 30 years ago,” says Peter Saville, who designed the Yohji Yamamoto catalogues between 1986 and 1990 and again for Spring/Summer 1992. In 2014 he was responsible for the prints for Y-3, the line Yamamoto designs for Adidas. This was launched in 2002, making it the first major designer-sportswear collaboration. The graphic designer called this later collection Meaningless Excitement; it was printed with ‘meaningless’ words and slogans – a brave commentary on the banality and oversaturation of fashion and popular culture more widely. “Yohji invites you to work with him and waits for you to do that work,” Saville continues. “He doesn’t say what he wants, doesn’t give a brief. He has chosen you because he has chosen you, for what you do, and who you are. So then he steps back and lets you be who you are.”

Of the motivation behind his collaboration with Adidas, overseen by Fabre-Bazin, Yamamoto, for his part, says: “About 20 years ago I found that my creations weren’t working on the street. I felt I had come too far from the street. I was shocked by our new culture, by businessmen, in the morning, going to the office very nicely suited and wearing sneakers. I was shocked by sneakers. So I thought, maybe working with sneakers, I can come back to the street. Hermann Deininger [the late and visionary chief marketing officer of Adidas] was a very fat, arrogant man, but nice – he accepted my request, so we started working together. I was invited to the Adidas company in Germany and I made a small fashion show. I didn’t expect it to become so big.” It has also paved the way for later tie-ins with fashion, including Rick Owens, Stella McCartney and Jeremy Scott, and potentially to a whole contemporary subset of fashion, fusing high-performance sportswear with designer clothing for everyday.

It is a mark of the truly great designer that they transform not just the runway but the way people dress far beyond that. Yamamoto is one of very few who can make that claim, though he is too modest a soul to do so and, in some ways, has struggled with the transition from avant-garde to great, since.

“Gradually,” the designer explains, “between seven and ten years passed, people started calling me maestro. I was surprised. I’m walking on the dark side of the street, why do I have to be called maestro? I’m not maestro. I’m just an anti, a punk designer. That was comfortable. Being maestro you have to be very tough. I’m sorry to say but I’m the leader of the family, the leader of the company. Being the leader of everything is kind of hard. So it’s natural that the desire to disappear comes up. Sometimes the responsibility is too much. But when I do fittings, when I start fitting for a new collection, only that moment I become very healthy and excited. A new outfit, the model changes, she comes out. Wow. That makes me happy, sad, angry, many emotions, but I become strong. That is the greatest moment.”

“I’ve been thinking, from the beginning, that fashion shows themselves are really close to Japanese traditional Noh,” he continues. He is referring to the classical Japanese musical theatre, performed since the 14th century and the oldest in existence today. Its name is derived from the Sino-Japanese word for ‘skill’ – it is stylised and formal, ritualised and extreme. “The actor comes out slowly, very slowly, and walks to the centre of the stage. They don’t speak. They don’t act, or at least only very carefully. Sometimes the audience doesn’t know the story, doesn’t understand. For fashion shows, the model wears a new outfit, walks out, doesn’t sing, doesn’t chat, doesn’t act, just walks and comes back. She is passive. But when the model wears that new outfit, something happens. And I like that. The audience looks at the model and the outfit walking and feels what? I don’t know. It’s a communication, from one mind to another, an exchange of emotion. I never actually see that because I’m behind, backstage. I don’t watch anything on a monitor because I’m too busy, all the way through, checking outfits. When models comes back, though, sometimes they bring emotion with them and then I feel, ‘Oh, maybe she made a strong connection with the audience.’ Sometimes not.”

Anastasia Barbieri, contributing editor to Vogue Paris, modelled for Yamamoto in Japan and styled Guinevere van Seenus for the cover story, shot by Paolo Roversi, of A Magazine, curated by Yohji Yamamoto in 2005. “In Yohji’s shows you always find a certain poetry,” she says. “Sometimes they are theatrical, sometimes dreamy, sometimes more rigorous. You are always surprised. Yohji is a gentleman. You can feel a certain sensuality that is never obvious, you can feel the love – the worship – he has towards women coming through in the clothes. He is an incredible human being and an incredible designer – a master.”

“Yohji is profoundly thoughtful in every choice he makes,” says Pat McGrath, who has designed the make-up for Yamamoto’s women’s shows since 2000. “He has given me the opportunity to dive into the architectural aspects of make-up design. I use a completely different set of brushes and tools for Yohji’s shows. You cannot imagine the emotion woven into his garments: His clothing brings out confidence and a bold expression of self. You don’t wear Yohji, you come to life in it.”

“When I first met Yohji I thought, ‘I wish my dad could have been that cool,’” says Eugene Souleiman, responsible for hair since 1998. “He is an extremely complicated human being, I think. We share the fact that we are very methodical in our approach but very open to change. When you look at the clothes on a hanger, you don’t feel them. You only feel Yohji’s clothes when they’re worn. He understands the space between the body and the clothes and how clothes move in life. He understands the weight of fabrics. Yohji is a phenomenal guitarist, like Ry Cooder. He can sing and he sounds like Serge Gainsbourg. Whatever he touches is really, really special. What you hear, what you see, how you feel, the ambience, the rhythm, there are so many layers and layers and layers to what Yohji does. The connection between them is soul, there’s a longing, a starkness, a romance, a darkness to his work.”

The conversation between Yamamoto and myself turns, as it always must, to the colour – or non-colour – black. “I remember sitting outside the Deux Magots or Café de Flore, because I smoke,” he says. “I like looking at people passing by. Almost all of them, almost all the young people, ordinary people, are wearing black. It’s not my fault.” Again, he’s laughing. “But because of that, the Quartier Latin became beautiful. Can you imagine if people were wearing awful colours, awful flower prints, I would die. In Tokyo, maybe because of the power of advertising, the power of magazine advertising, young people are like groupies, wearing very new outfits, beige, blue. It’s quite hard to find independent, beautiful people in Tokyo. When I started my career there, when I walked in the street, I would look at some people and think, ‘How beautiful. Don’t go. Don’t go.’

“Black, typically, has different meanings. One, it is not disturbing people’s eyes. Another, it is very strong, suggesting, ‘I don’t need colour.’ That’s kind of a point of pride. A third, after high-school age, parents don’t buy expensive clothing for their children, so their children buy cheap vintage jeans, cheap vintage black outfits. And I like that.”

Although Yamamoto is flattered by any copying of his designs – “Being copied is OK, being copied is an honour,” he says – he is far from enamoured with what he describes as fast fashion, which, it almost goes without saying, is the antithesis to everything he believes in. “They make everything by computer, all the outfits looks the same,” he says. “They print all the fabrics using cheap labour, in different countries. The people there have no experience of wearing fashion and that’s terrible. Even if they wanted to, they wouldn’t be able to afford it, and that unfairness makes me angry, even sad. They make all the clothes on a sewing machine. People’s fingers are cultured but these people’s minds are probably vacant. They don’t understand what they’re doing, can’t wear what they’re doing, so the outfit comes out and it means nothing.”

For Yamamoto, the way one chooses to dress oneself speaks volumes: physically, intellectually, emotionally, even spiritually. “Choosing an outfit is choosing a life,” he says.

Yamamoto also designs menswear and his men’s following is similarly loyal. But: “I am a man. Born a man and still a man. I never became gay. I can easily understand how do I feel when I wear this? I can imagine. But for women’s clothing … I still don’t understand how a woman feels when she wears my clothes, so I become naturally more serious when I design for women. I also personally think that if you want to be a fashion designer, a costume designer, a dressmaker, you have to be successful making things for women. Men’s bodies and women’s bodies are so different. A woman’s body has delicate, skinny shoulders. Women have very complicated, round, beautiful ‘mountains’”. He doesn’t worry about being politically correct, or outspoken. Is he referencing a Shakira song? It’s clearly unlikely. “It is very difficult to work fabric around that. For men it’s quite easy – shirt, jacket, pants. It hands straight. In particular, I am addicted to the shape of a woman’s back. I love it. Especially the curve, the narrow waist, then, gradually, the hip. The back is most important to me.” And here once more: “‘Don’t go. Please.’”

As newly appointed fashion editor of The Guardian in 1996, my first major interview was with Yamamoto. The location was Blakes Hotel in London and I was as excited as I was intimidated. The reason for the meeting – allegedly – was the launch of his first fragrance with Jean Patou. We took our seats around a large table in the garden: Yamamoto flanked by two serene women of different ages, each wearing his languid, black designs; me flanked by an army of besuited executives from Patou. The perfume in question was a chypre – generally believed to be the most complex and elitist family of scents – created by the esteemed Jean Kerléo, in-house perfumer for Patou at the time. It was called – simply and inevitably – Yohji.

My dutiful opening question: “Were you inspired by other great fragrances?”

“I don’t really like any perfume,” came his reply.

The first of the women accompanying – minding? – Yamamoto was silver-haired Irene Silvagni, who has worked with him on the visual direction of his company since 1992. Prior to that she was a fashion editor at Vogue Paris. “As a journalist I had great admiration for Yohji,” she says now. “When he asked me to work for him I almost fell to the floor. I went to Japan and have been with him ever since, and have never regretted it. We are like brother and sister, and I love what he does. Yohji and Comme des Garçons really changed the fashion world. They broke all the rules. I remember once in New York, Yves Saint Laurent received a prize and we spoke because I had become close to him also. He said to me, ‘I am very, very impressed by these two Japanese designers.’ When we came out of that first Paris show, I remember one writer, for a very important magazine, saying, ‘It was like Hiroshima’. I said, ‘What are you talking about? It’s a new door opening for fashion.’ And that’s exactly what happened. For many years I was helping with the collections – not helping to design them, but saying whether I liked things or not. This is nice, this is nice, this is nice. Yohji is a very good person. He’s a very quiet person and lovely to work with. Everybody who works with Yohji loves him and has great admiration for him. I don’t think his clothes ever go out of fashion. He loves and is fascinated by women. The things I own are all still wonderful. I went to the Gucci show in Arles [Gucci’s resort presentation took place in that city in May this year] with a journalist friend. I was dressed in Yohji, as always, very simply, wide-legged pants and a jacket. I’m 76 years old and so many people said to me, ‘Oh you look wonderful.’”

The younger woman was Nathalie Ours, first co-ordinator then PR of Yohji Yamamoto in Tokyo from 1987, after which she became PR director in Paris until 2005. Today she is a partner at PR consulting in Paris but, like Silvagni, she remains loyal. “Every time I see him is like the first time,” she says. “I know him but there is something that still makes me feel very little in front of him. His way of talking, the way he moves his hands, the way he smokes. It’s the spirit around him. When I was in Tokyo I was lucky enough to see him in fittings. He had such concentration. His eyes were like lasers. He would take the scissors and barely touch the fabric, but you’d immediately see a change. There was such delicacy and respect in the way he placed fabric on the body of the model. For me, it’s very simple. He is one of the great masters of fashion. In the 1950s there was Dior, then there was Balenciaga and Saint Laurent. Yohji is that level. When you wear his clothes you feel protected. There’s always space between the body and the clothing so you’re not constructed, constrained. Another thing that is often missing in fashion now is that you can feel the hand, the hand and the mind of someone. You touch Yohji’s clothes on the rack and they talk to you. My first job was working for Yohji and I learnt everything from him but especially a way of looking at things. He taught me not to look for obvious beauty in things but to find another angle. Something you think is quite terrible at first sight maybe has beauty, too. And beauty is not perfection, imperfection is maybe the most important thing, because it’s there that you see the hand of the person who has made it. Perfection is too easy. A machine can do that.”

The director Wim Wenders first came across Yamamoto’s clothes when his girlfriend at the time, Solveig Dommartin, was “transformed” by them; she wears Yohji in the closing scene of Wings in Desire. In 1989 Wenders spent a full 81 minutes attempting to unravel the enigma that is Yamamoto in the remarkable documentary Notebook on Cities and Clothes. The film director and the designer remain great friends. “What secret had he discovered, this Yamamoto?” Wenders, who also narrates the movie, wonders. “What does he know about me? About everybody?” That there is a profound understanding of humanity in every seam of Yamamoto’s clothes is integral to their allure and the almost devotional nature of those who wear him. What does he know about us? More than most.

“It [the film] started with a project for a short film that the Centre Pompidou wanted to initiate, based on an encounter between Yohji and myself,” Wenders says today. “I was curious to meet this man whose clothes somehow had this magic built in. Well, we did meet, we liked each other and felt that there was a good connection between us, some sort of distant brotherhood between two men born around the same time, and even if Japan and Germany were far apart, we sensed that we shared something in our upbringing. Maybe it was the postwar blues, maybe it was the Americanisation of both Japan and Germany, maybe we both just liked the same music, the same writers, the same photographs, shared a similar inspiration. Anyway, we decided not to be trapped inside the formula of this limited short film and opted to venture into a long film together that I was going to direct and that my company was going to produce together with Yohji’s. It was going to be an exploration of Yohji’s work and the sources of his inspiration, some sort of essay film that I ended up shooting more or less alone, as a one-man crew, with a few exceptions. The film was shot over the period of a year, some in Tokyo, some in Paris, and we still premiered it at the Centre Pompidou, as they had had the good intuition to bring us together.

“His influence on younger designers is enormous. His importance in fashion is historic. Nobody else has worked in that field with so much persistence and so convincingly. I still have suits and shirts, shoes and coats made by Yohji 20 or 30 years ago, and they get better with age. Some of them I have worn for years, and they are still solid, classy, indestructible, with tenderness and tradition and a feeling of time built into them that no other clothes transport. Yohji now is almost a living legend, but he is still just as humble and works just as hard as always.”

In the end, it is really only doubting Yamamoto who underplays the value of his clothes. “Sometimes when I see women wearing them I wonder, ‘Is it too much?’” And such self-questioning is surely at least in part the secret of any success. “But I prefer women to wear my clothes in their own way. That for me is a big surprise, a big happiness,” he says.

Yamamoto is wearing his own designs as always. Black fedora, black shirt, black trousers, black shoes. He smokes almost continuously. Around his neck, suspended on a silver chain, is an American dog tag and a sword. “Because I am always thinking, imagining about disappearing, without noticing. Maybe someone saw Yohji after, in a small town, I don’t know where. That was the last time,” he says.

I ask Yamamoto whether he is a religious man. “Why do I have to pray in front of God?” he replies. “Who is God? What is God? There are so many accidents in the world, also in Japan. Boys and girls, maybe two or three years old, passing away in traffic accidents. I ask God, ‘Why are you testing? Why are you testing?’” He pauses. “I get angry.”

If Yamamoto’s work is synonymous with emotion, those emotions inevitably include anger. At the start of his career, Yamamoto was angry about the clothes women were forced to wear; his fashion shows evoked xenophobic, misunderstood anger in onlookers, who couldn’t comprehend what they were looking at. They were a vocal minority. Yamamoto has been angry with the system of the industry, the homogenisation of creativity, the idea of fashion itself, with its inbuilt and inherent obsolescence, endless waste. But out of anger came love. Yohji Yamamoto creates clothing that expresses love more than anything else, attracting men and women that love it in return. And that is glorious.

For now, he is preparing to return home to Tokyo, where he lives alone with his dog. “A big dog, a girl, very tough, very wired,” he says. “She loves me, I love her. We’re always together. I’m just with her. We walk together very early every morning. In Tokyo there is a huge cemetery garden, it’s so beautiful in the morning air, in the fresh air. And the sun comes up and I have my first smoke there in the cemetery. It’s delicious,” Yohji Yamamoto says.

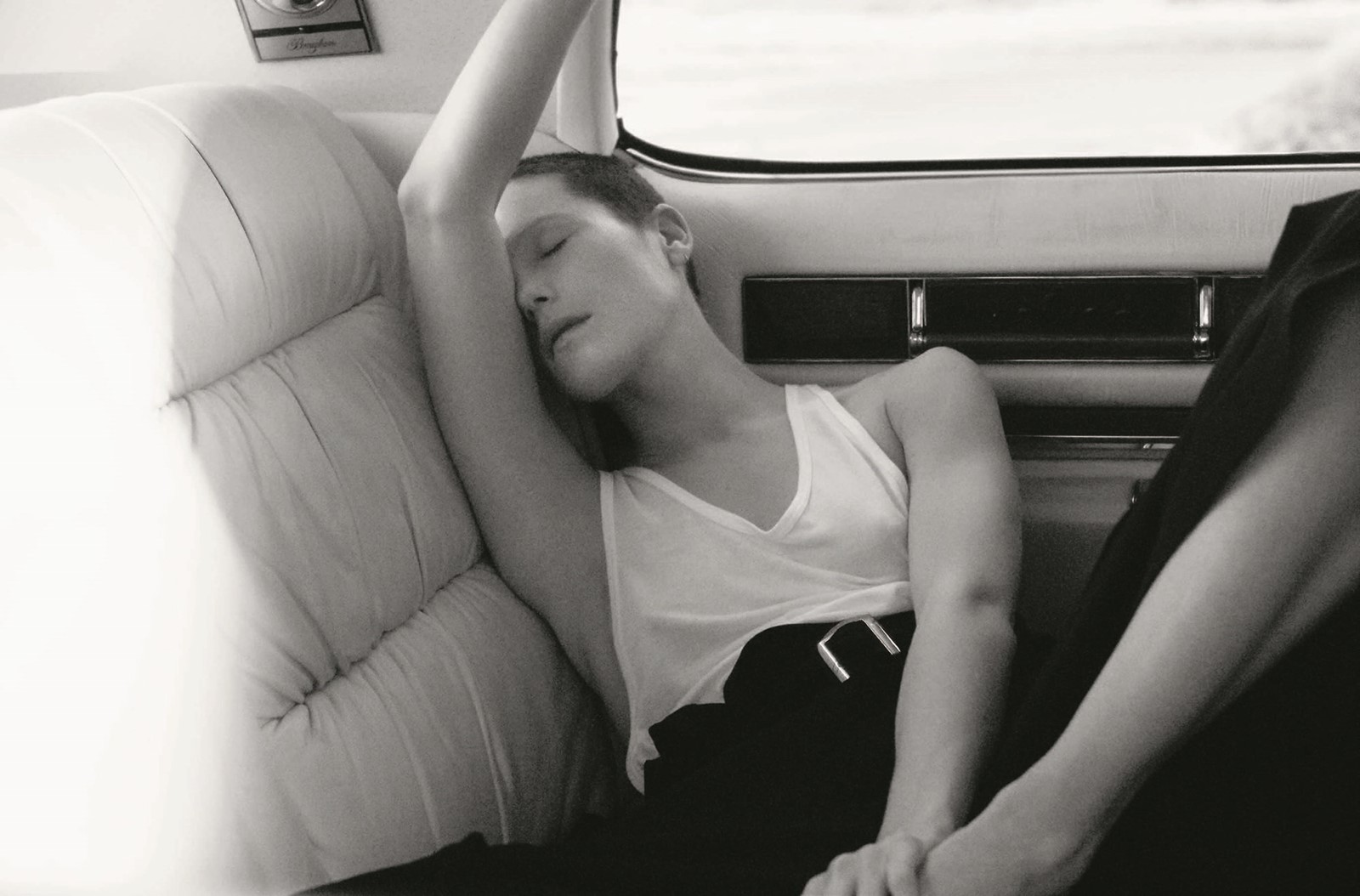

Hair: Duffy at Streeters. Make-up: Lucia Pieroni at Streeters using Clé de Peau Beauté. Models: Betty Belle at Next Models London, Luna Bijl and Mame Thiane Camara at Premier, Yaara Benbenishty at Elite, Martina Boaretto, Dree Hemingway and Aurora Talarico at Viva London, Hana Jirickova and Leah de Wavrin at IMG, Veronika Kunz and Othilia Simon at The Squad, Rebecca Leigh Longendyke at Storm Management, Lila Moss at Kate Moss Agency and Niko Riam at Milk. Casting: Art House and with special thanks to Jess Hallett at Streeters. Set design: Max Bellhouse at The Magnet Agency. Manicure: Ama Quashie at CLM Hair and Make-up using Dior Backstage and Capture Youth by Dior. Styling assistants: James Campbell, Lydia Simpson, Aurora Burn, Angus McEvoy and Grace English. Hair assistants: Lukas Tralmer, Natalie Shafii and Mike O’Gorman. Make-up assistants: Mirijana Vasovic, Shelley Blaze, Bernadette Krejci and Manisha Parti. Set-design assistants: Alexandra Leavey, Tilly Power and Georgia Coleman. Manicure assistant: Zaida Ibrahim-Gani. Production: Laura Holmes Production. Production runner: Caspar Bucknall. Post-production: SKN-Lab.

This full story originally featured in the Spring/Summer 2018 issue of AnOther Magazine which is on sale internationally now.