The archives of Yves Saint Laurent – arguably the greatest fashion designer of the late 20th century – are contained within the Napoleon III hôtel particulier that formerly housed his maison de couture, at 5 avenue Marceau, Paris. Clothes are kept in every nook and cranny, in spaces formerly occupied by the ateliers that produced Saint Laurent’s superlative tailoring and grand evening dresses, but also in the staff canteen under the eaves, and a building next door that housed administration. Despite the renovations, walking through the glass double doors and Second Empire stucco architraves is like walking back in time. Saint Laurent’s studio has been painstakingly reconstructed, with rolls of fabric, swatches of embroideries and trays of buttons and bibelots, gathering dust. Below, two salons on the first floor have been decorated with a facsimile of the house’s original decor – parchment-coloured walls, milky-crystal chandeliers, heavy brassica-green damask drapes. A pair of Warhol portraits of Saint Laurent stand sentinel over a settee in the same fabric, overstuffed so that it resembles a ripe vegetable. The air is eerie and quiet. Time stands still.

It is exactly what Saint Laurent would have wanted. After all, he was the only fashion designer who envisaged his clothing, within his own lifetime, as museum exhibits – from the middle of the 1980s, the couturier would write the word “Musée” on the labels of various garments, in his slightly shaky hand, a flourish to the ‘s’, denoting which garments from the collection should be preserved for posterity, reserved for the then-hypothetical museum in his name. It appears alongside the name of the model (“Naome” for Naomi Campbell) on the $100,000 Sunflower jacket from his January 1988 haute couture collection, embroidered by François Lesage with a recreation of Vincent Van Gogh’s paintings from a century earlier. It is a masterpiece, depicting another masterpiece. History was always important to Saint Laurent. He knew he was making it.

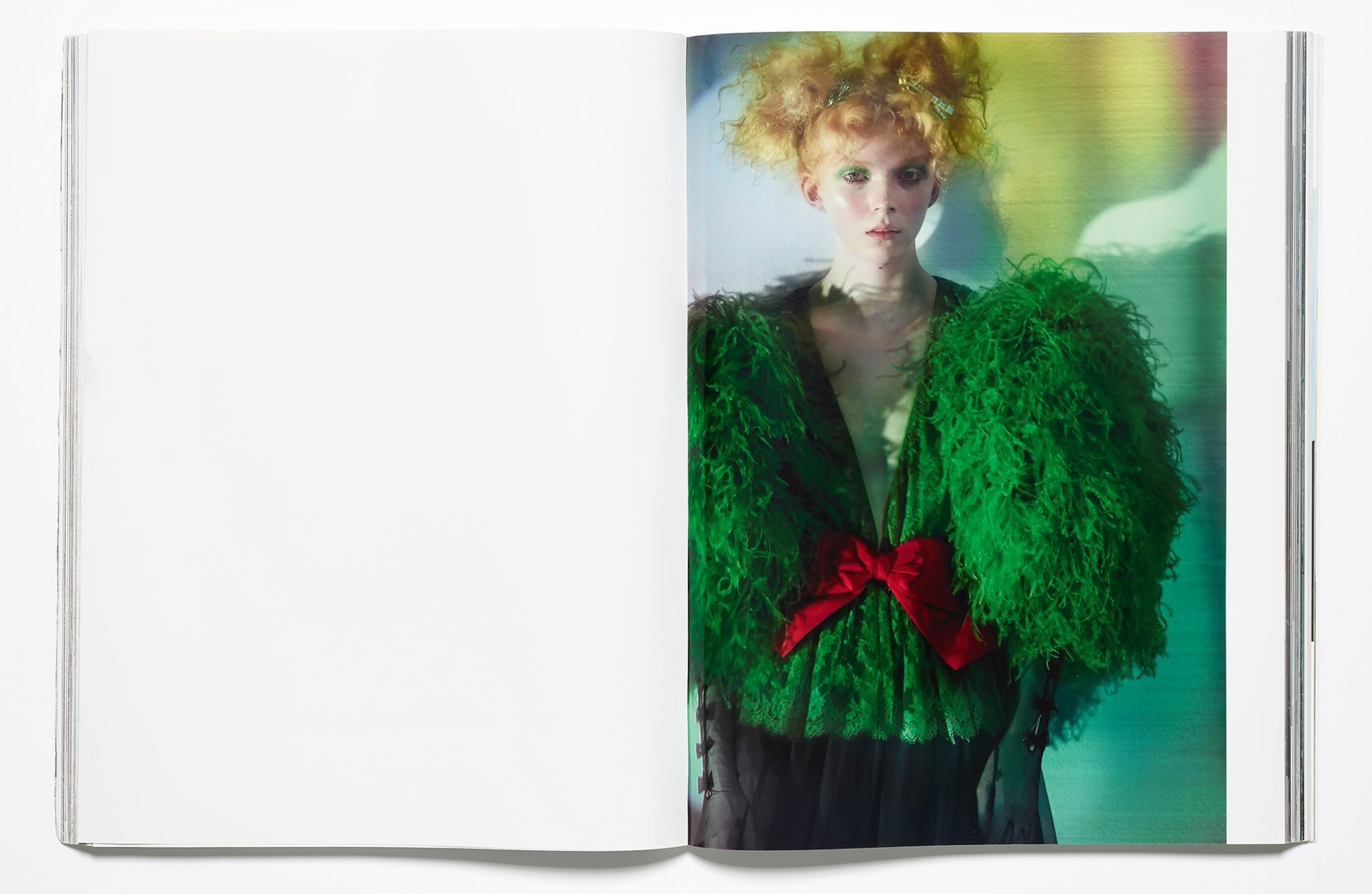

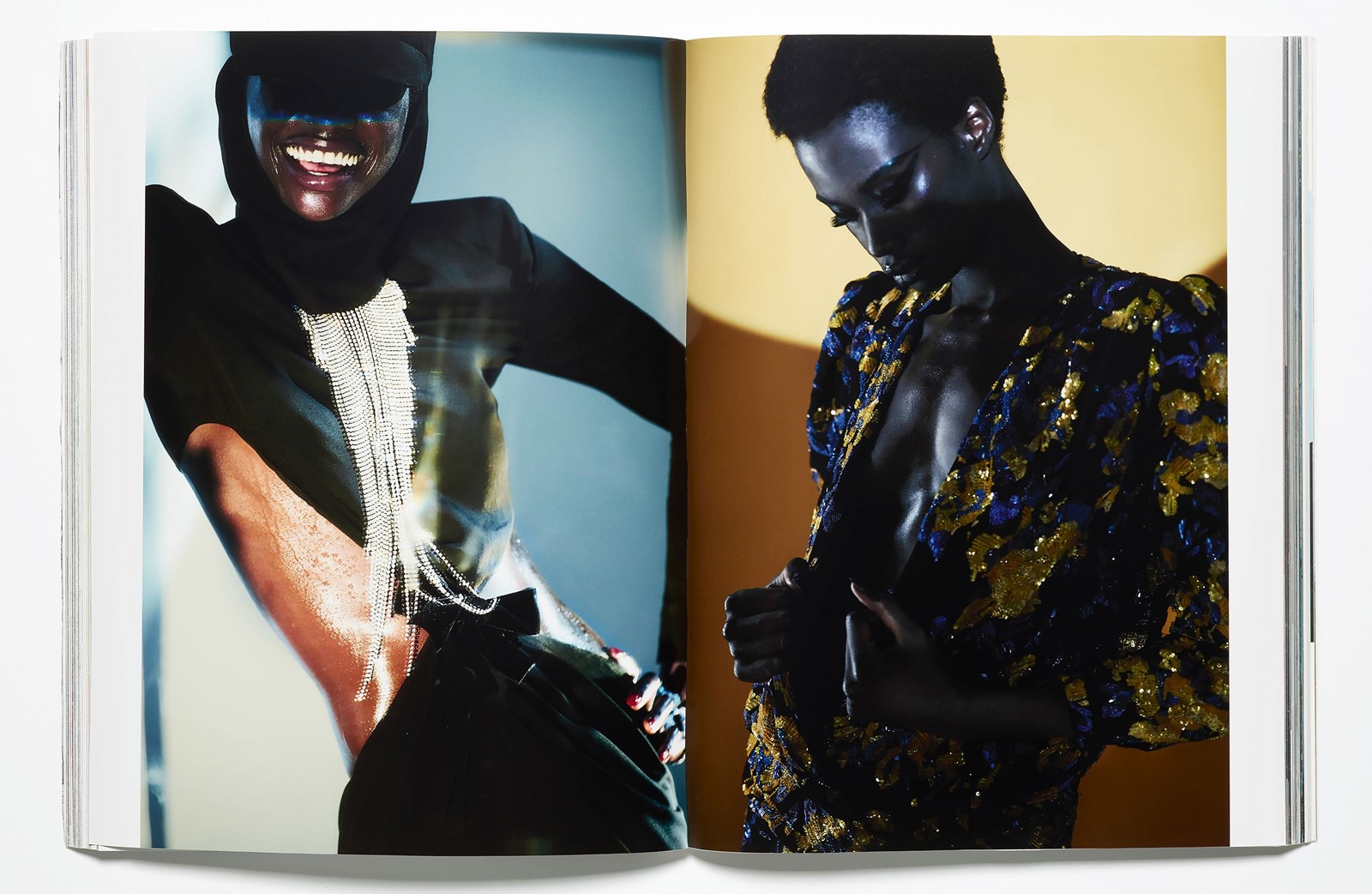

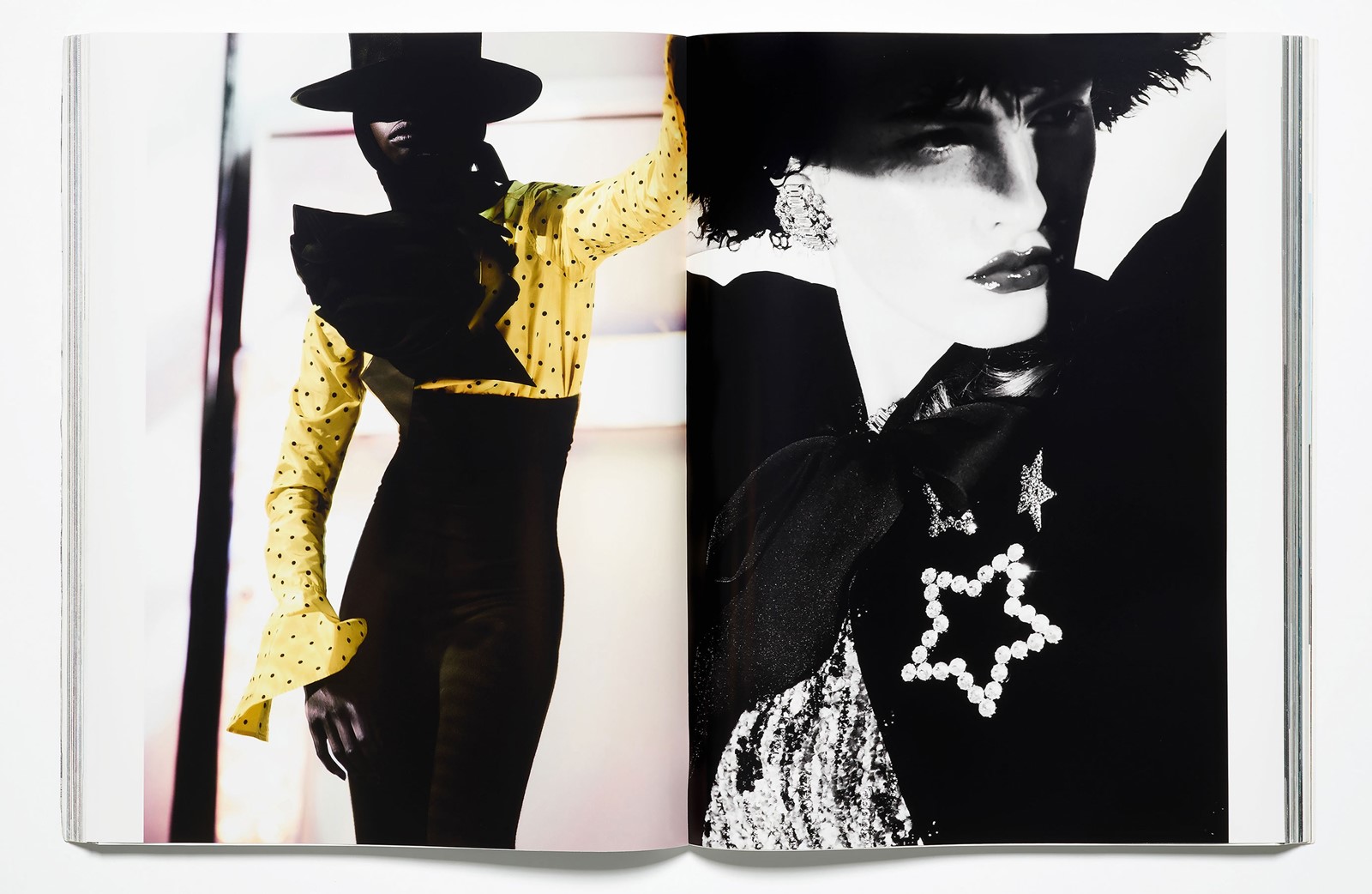

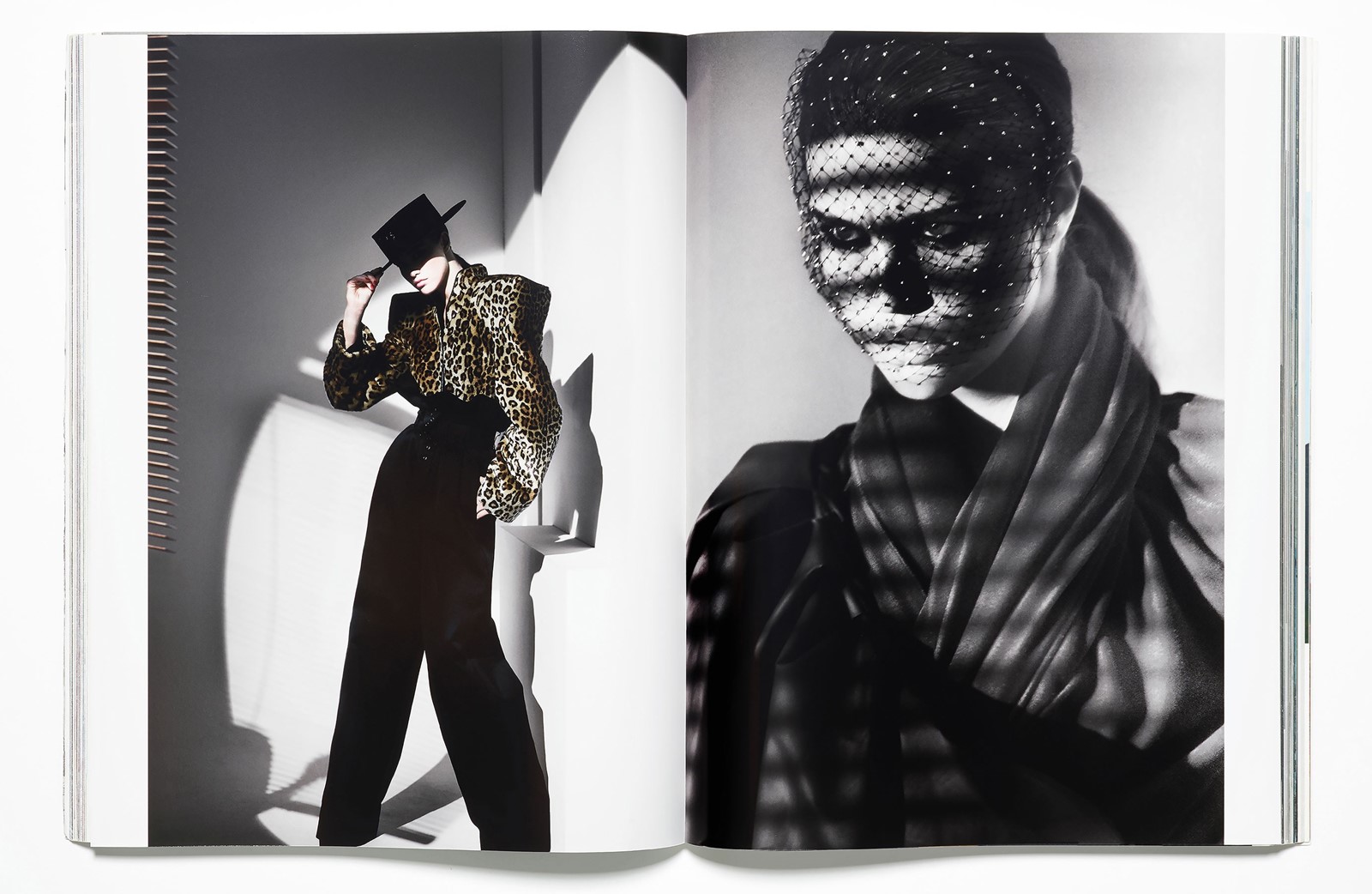

This year marks the tenth anniversary of Yves Saint Laurent’s death, and last year, his haute couture house reopened as the Musée Yves Saint Laurent Paris, devoted to celebrating his life’s work. But the celebrations continue outside the walls of the avenue Marceau, where Saint Laurent is very much alive, through the clothes on women’s backs. The echoes of Yves Saint Laurent across the Autumn/Winter 2018 collections were pronounced, specific. The most notable was Anthony Vaccarello’s, the latest exegesis of Saint Laurent’s future, ruched dresses in richly coloured archival embroideries, and carved, graphic black shapes with Cossack boots. If these bore the Saint Laurent imprint literally – across their labels – others were writ metaphorically but large with his hand-writing. Saint Laurent’s shapes, Saint Laurent’s shoulders, the Saint Laurent spectrum of satsuma orange and frosted pink, of violet and virulent green, they all appeared time and time again. Saint Laurent’s ghost haunts designers. His spirit lives on.

So what? Throughout contemporary fashion, reflections of Saint Laurent are frequent, insistent. You barely need to look for it, so important was his legacy. Indeed, it’s difficult for a designer to avoid Saint Laurent because he basically invented the style of the latter half of the 20th century. When a designer creates anything, from a leather jacket, to a trouser suit, to a coloured fur coat, it inevitably touches on Saint Laurent – because Saint Laurent was, invariably, the first.

Broad statement; let’s unpack it. In 1960, Yves Saint Laurent – then at Christian Dior, where he inherited the mantle of the founder in 1957, aged just 21 – created a collection we call Beat, but which Saint Laurent named Souplesse, Légèreté, Vie – Suppleness, Lightness, Life. It was inspired by the life Saint Laurent saw on the streets of Paris, specifically that of Left Bank existentialists, and contained an outfit titled Chicago, a black crocodile jacket trimmed in mink. It caused a furore – the first whiff of the street ever seen in an haute couture salon. Chicago was also credited as a blouson noir: doublespeak, that was a pejorative term used by the French bourgeoisie for the hooligans marauding around the boulevard Saint-Germain. With its Youthquake leanings, the Beat collection not only prefaced a cultural shift that would surrender control to twentysomethings during the 1960s, but the inversion of a fashion system that would see subcultures inspiring high fashion through until the present day. The trouser suit came later, in 1966 – Le Smoking, a men’s tuxedo proposed for women at a time when they could still be turned away from fashionable restaurants if they were wearing trousers. The socialite Nan Kempner, a Saint Laurent devotee, was refused entry to La Côte Basque in New York in 1968 for that reason (though she dropped the trousers and walked in). The fur coat – a fat fox chubby in emerald – comes from his Spring/Summer 1971 haute couture collection, an unabashed ode to the 1940s the press drubbed as a “Tour de force of bad taste”, but which he himself dubbed Libération.

Liberation is a vital term in Saint Laurent’s semantics. It’s what he stood for, overwhelmingly – liberation of women’s bodies, liberation from morality, liberation of couture and the couturier from the conventions of taste. Saint Laurent eased women’s clothing, freed their figures – his 1958 debut as head of Christian Dior, the Trapèze, deconstructed the lines of the house, removing internal structure, lightening the load. That was an impulse Saint Laurent pursued throughout his work for the house – as artistic director but, before, as a first assistant invisibly guiding the hand of his maître, tugging his vision towards a future. It was he who created shifts and chemises and, in Monsieur Dior’s penultimate collection, a silhouette simply named Free. It was a precursor to Saint Laurent’s obsession with freedom, which encompassed both the physical and psychological. That Libération collection – sometimes, retrospectively, more bluntly labelled the Scandal collection – emblematises the former, and Saint Laurent’s overriding urge to épater la bourgeoisie. Other couturiers had caused sensations with their work – Dior with his 1947 New Look, Paul Poiret with his hobble-skirted odes to the Ballets Russes in the 1900s – but never with Saint Laurent’s precision of intent. Saint Laurent purposefully thumbed his nose at received notions of elegance and luxury, challenging perceptions of what a couturier – and a couture house – could do. Other designers were transformed into followers. The flirty, fluid crepe dresses, bold colour and platform shoes of his scandalous 1971 collection set the template for the 1970s, while its broad shoulders were a full decade ahead, prefacing the silhouette of the 1980s. They became so associated with the couturier that a special breed was named the Saint Laurent shoulder, meticulously constructed with light, pliant padding and upturned at the edge with a swaggering confidence they also afforded their wearers.

Marcel Proust wrote, “Remembrance of things past is not necessarily the remembrance of things as they were.” Proust was a Saint Laurent obsession: quotes were framed on his studio walls; he named each of the bedrooms in his country château after the characters of Proust’s opus, À la recherche du temps perdu; once, when mistakenly given a bouquet of arum lilies rather than the Proustian Casa Blanca lily, he showed his displeasure by snipping off each of the flowers’ heads. While remembrance of Saint Laurent’s fashion achievements past is crystal clear, what appears hazier through the lens of history is their impact. The revolutions he wrought in the 1960s, for instance, have now become commonplace, part of the everyday vernacular of clothing. That isn’t pejorative – it is, again, exactly what Saint Laurent wanted. He once declared that he wished he had invented blue jeans: “the most spectacular, the most practical, the most relaxed and nonchalant. They have expression, modesty, sex appeal, simplicity – all I hope for in my clothes.” Saint Laurent may not have invented those, but much of what he did bring to the universe of couture accomplished the same thing. The pea coat, the caban, the trench coat, safari jackets (which the French so evocatively dub Saharienne), trousers for women – all of which, like jeans, he did not originate but which he transformed from hitherto utilitarian, masculine garments into sexy and daring high fashion. This distinct vocabulary of items has now become part of every woman’s everyday wardrobe – and while not every trouser suit evokes the brilliance of Saint Laurent, they all form a part of his legacy.

I met Pierre Bergé, Saint Laurent’s former lover, the house’s co-founder and protector of both, shortly before his death in September 2017. Aged 86, he was confined to a wheelchair, visibly ill (he would die of myopathy, a neuromuscular disorder), irascible, intriguing and, above all, passionate. The latter was Bergé’s calling card – his fearsome temper was legendary and still present, undiluted and as recognisable as his face with its proud nose, shock of silver hair and raised, jutting chin, familiar from the many images of him captured at Saint Laurent’s side. The buttonhole of his lapel was stitched with a hairline tricolor loop of ribbon that signified Bergé was a Grand Officer of the Légion d’honneur.

“There were great, great fashion designers in the last century,” Bergé told me, passionately. “But only two – Chanel and Saint Laurent – go to the social field.” If Chanel freed women from corsets and cumbersome long skirts, Saint Laurent empowered them, dressing them to compete with men in trousers. In inventing designer ready-to-wear, he made fashion accessible to every woman. It was a revolution.

That’s business. But the passion here was personal first, professional second: lives still entwined 50 years after meeting and over half a decade after the closure of the couture house, in the days prior to Saint Laurent’s death from brain cancer in 2008 the men were joined in a pacte civil de solidarité – a same-sex civil union. Talking of the emotion attached to Saint Laurent, Bergé softened. Emotion is the real reason he began work on the museum. “We kept everything. Everything,” he said. “I have everything from the sketches he made in Marrakech – two weeks in December, and two weeks in June – until the show at the Hôtel InterContinental. You have all the process.” Bergé smiled, rarely, transformed. “The whole life of the dress. That means the whole life of this house. That means my whole life.” Indeed: for 40 years, Bergé was the CEO of Yves Saint Laurent Haute Couture; for another 15, he headed the Fondation Pierre Bergé – Yves Saint Laurent (an earlier incarnation of the now-museum), guarding the legacy he had helped create until his own death, just weeks before the Musée Yves Saint Laurent opened. But his real role was more abstract: as keeper of the faith. In his honey-coloured office, another Warhol of Saint Laurent stood, this one like a Catholic icon.

Monsieur Bergé was wearing a tie in purple silk, which seems a particularly Saint Laurent shade. A moiré skirt of the same colour, from Saint Laurent's 1976 Russian collection, hung in the archive above us; the launch of the house's fragrance Opium, in 1977, was awash with purple, to match the bottle; it was the hue of the first sell-out Saint Laurent lipstick, No 19, from 1978. So many allusions, so many layers of Saint Laurent history, crammed into a knotted slither of fabric. What other designer's work could evoke so much from so little? Bergé began archiving Saint Laurent's work as he created it, in 1964, decades before other houses – and even Saint Laurent himself – realised the value of such collections. When I asked him why, his answer was plain: “Because I was sure Saint Laurent was the greatest designer of his time.” Although his designs were, and continue to be, deified, and the maison itself was chapel-like in a manner not seen since the monastic atmosphere of the house of Cristóbal Balenciaga – where voices among the white-clad atelier staff were rarely raised above whispered murmurs – the house of Saint Laurent was not devoted to veneration of the self. Rather, it was about reverence and respect for women. “He exhibited a gentleness, even a tenderness, that indicated a respect for the female body not far from worship,” observed Anthony Burgess in a 1977 profile of Saint Laurent for The New York Times Magazine. “Later, in a rare flash of English, he was to say to me that he looked on women as — the word sounded like ‘dolls’. ‘Des poupées?’ I asked, unbelieving. No, no, no not dolls – idols.”

If there is one element, one fil rouge that connects the disparate themes and obsessions of Saint Laurent, it is a love for and empowerment of women. Even a glorification. In 1965, he created a passage of dresses in the form of paintings by the Dutch modernist Piet Mondrian. Ingeniously constructed from blocks of wool jersey, with all fit seams integrated into the lines, the paintings were tailored to follow and flatter the female form. But more than just placing a painting on the body, Saint Laurent transformed the woman herself into a work of art. A year later, he did the same with brightly coloured pop art graphics inspired by Tom Wesselmann; in 1979, women became walking Picassos; in 1980, Matisse; in 1988, Georges Braque. There were also words by Guillaume Apollinaire and Jean Cocteau, and styles inspired by Shakespeare. Idols of art and literature, the lynchpins of culture, transformed into women, not the other way around. It could be argued – heretically – that the impulse debased the originals, vulgarised them, that by embroidering Van Gogh’s work on a jacket it became lesser, even if said jacket required 350,000 sequins, 100,000 beads and 600 hours of labour to realise. Which is perhaps true. Because in actuality, like those first Mondrian dresses, the works of art were tailored to the bodies inside them. The works of men, subjugated to the will of women.

In July 1976, Saint Laurent presented his own homage to the Ballets Russes, inspired by an escapist vision of the riches of Tsarist Russia, of vast silk skirts, lamé jackets trimmed in fur, with tasselled boots and sable kubankas. It was also the first of his haute couture shows to be staged in the vast gilded ballroom of the Hôtel InterContinental, on a raised catwalk – a pedestal. Women were elevated, celebrated. Which is, perhaps, why Saint Laurent’s style has such resonance today – a similar intent, from designers recognising that women once again need clothes to simultaneously empower and idolise them. Women were transformed under Saint Laurent’s hand and eye. Always, they became better versions of themselves.

Despite the mythology woven around him, both during his lifetime and since, Saint Laurent’s lines did not originate from the tortured depths of despair. Often, they came from the women around him – technically executed by Anne-Marie Muñoz, head of Saint Laurent’s studio for the duration of his couture business; and incubated through the tastes and on the bodies of a cabal of powerful women. Loulou de La Falaise and Betty Catroux were the most pointed muses, the first Saint Laurent’s right-hand woman of impeccable chic, the second an inspiring nightlife denizen whom he befriended. There was also Paloma Picasso, and Catherine Deneuve, and early on, Victoire Doutreleau, a former Dior model who moved with Saint Laurent when he established his own business in 1961. The often-ephemeral skills of these women are difficult to define today, to determine their exact roles and peculiar alchemy (bar de la Falaise, who created tangible jewellery and helped style the collections). But it was the sharp style of Catroux that influenced the Smokings, and the vintage Clignancourt chic of Picasso and de La Falaise that helped inspire the Libération collection – also an ode to the style of Saint Laurent’s mother in her heyday, as most designers’ best collections tend to be.

The codes and signifiers of Saint Laurent are complex, his style so varied, so far-reaching and wide-ranging across the four-decade span of his maison de couture (and his half a decade at Dior before) that it seems impossible to summarise. His work is a bundle of contradictions. If Saint Laurent is about elegance and restraint, the purity of Le Smoking, the ascetic austerity of his little black dresses, it is also about the coquettish frivolity of taffeta ruffles and lace and baby pink satin bows, about extravaganzas of embroidery and brocade, homages to artists and writers. It is about ball gowns and leather jackets, duchesses and hooligans. Punk is frequently credited with fracturing the style of the 20th century, of inventing the notion of anti-fashion fashion. Yet perhaps that notion originates with Saint Laurent, too, in styles that swung to polar opposites, and where the bride – both sacred and cash cow of haute couture – was treated with irreverence that bordered on disrespect. Albeit to the couturier, rather than the woman.

“Saint Laurent is the past,” said Bergé, when we met. Which is true. Saint Laurent is dead, now too Bergé, and many of their former devoted clients, Saint Laurent’s acolytes. The haute couture business closed in 2002. The clothes are entombed in shrouds of acid-free tissue, encased in cardboard ‘coffins’ (the actual term for archival storage boxes). But, he continued, “We place our feet in the past.” Bergé was referring to the museum itself, but at the same time the past of Saint Laurent feels remarkably present – omnipresent, even. Eternal.

Bergé continued, irritated. “Even if his garments are very modern and very now and very today. The creation is the past. Today is another world, don’t forget that. I hate the past. I hate nostalgia. That means I think a fashion designer today is not the same as 70 years ago. He has to look around him.” He paused. “But some things are not different. Inspiration, creation and women. When I say women, let me explain – it is because many fashion designers design for themselves, and not for women.”

The implication, of course, is that Yves Saint Laurent did. Which is, of course, very true – this was one of the few houses that conntinued to create made-to-measure clothes for a fervently loyal clientele as the influence of haute couture waned and the prices skyrocketed. But more than the physicality of women, Saint Laurent dressed the ideology of of women – as a movement. He dressed them for who they could be; his clothes liberated. The couturier himself referred to his maison as “the house of love” – a word forever associated with the label. Saint Laurent sent out cards hand-painted with the word; he embroidered it onto dresses, alongside lipstick kisses. Saint Laurent’s love was women. Luckily, his influence continues. Like Proust, fashion searches ceaselessly, relentlessly, for things past, to discover them anew. It never has to look far for Saint Laurent. His work is immortal, omnipresent. The beat goes on.

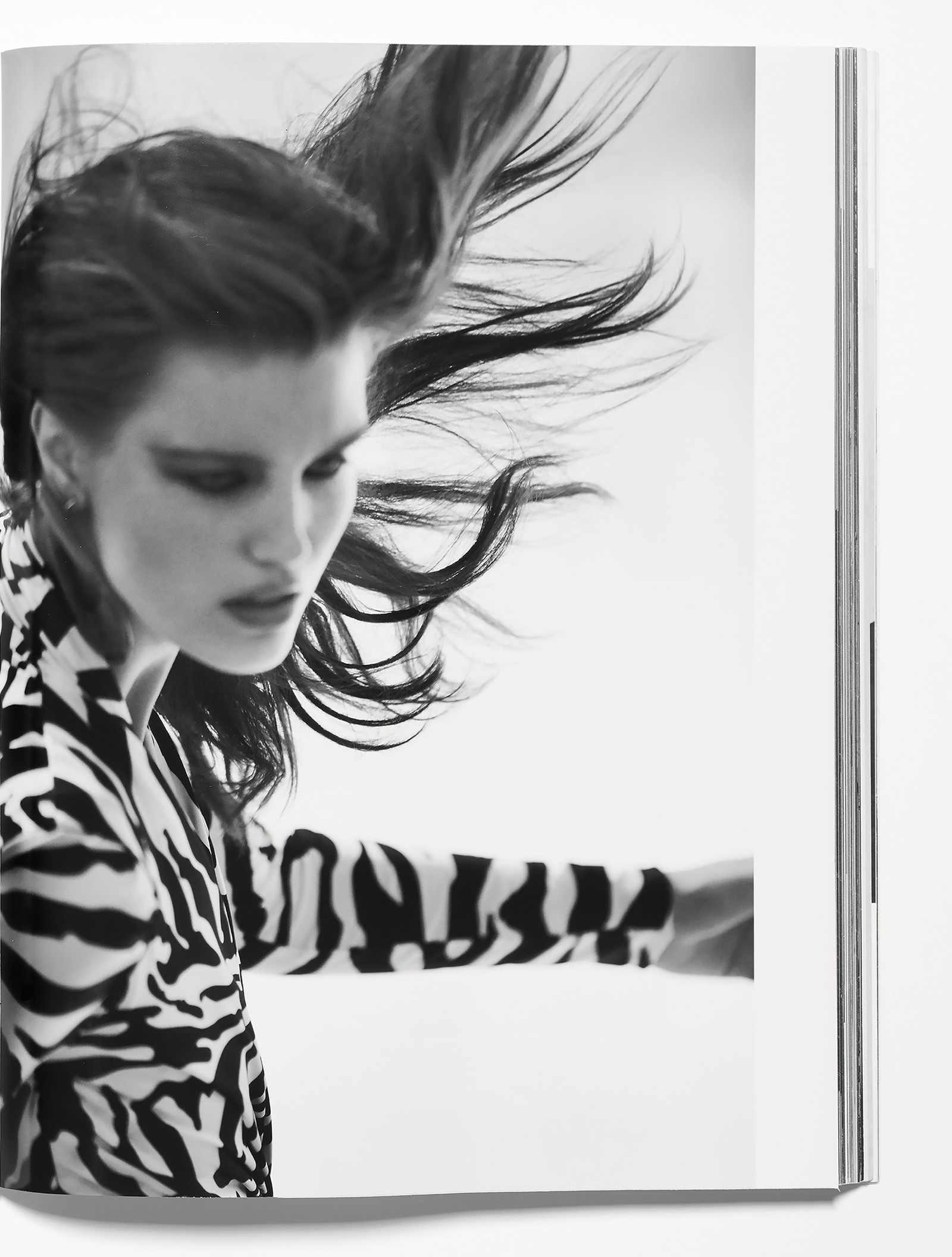

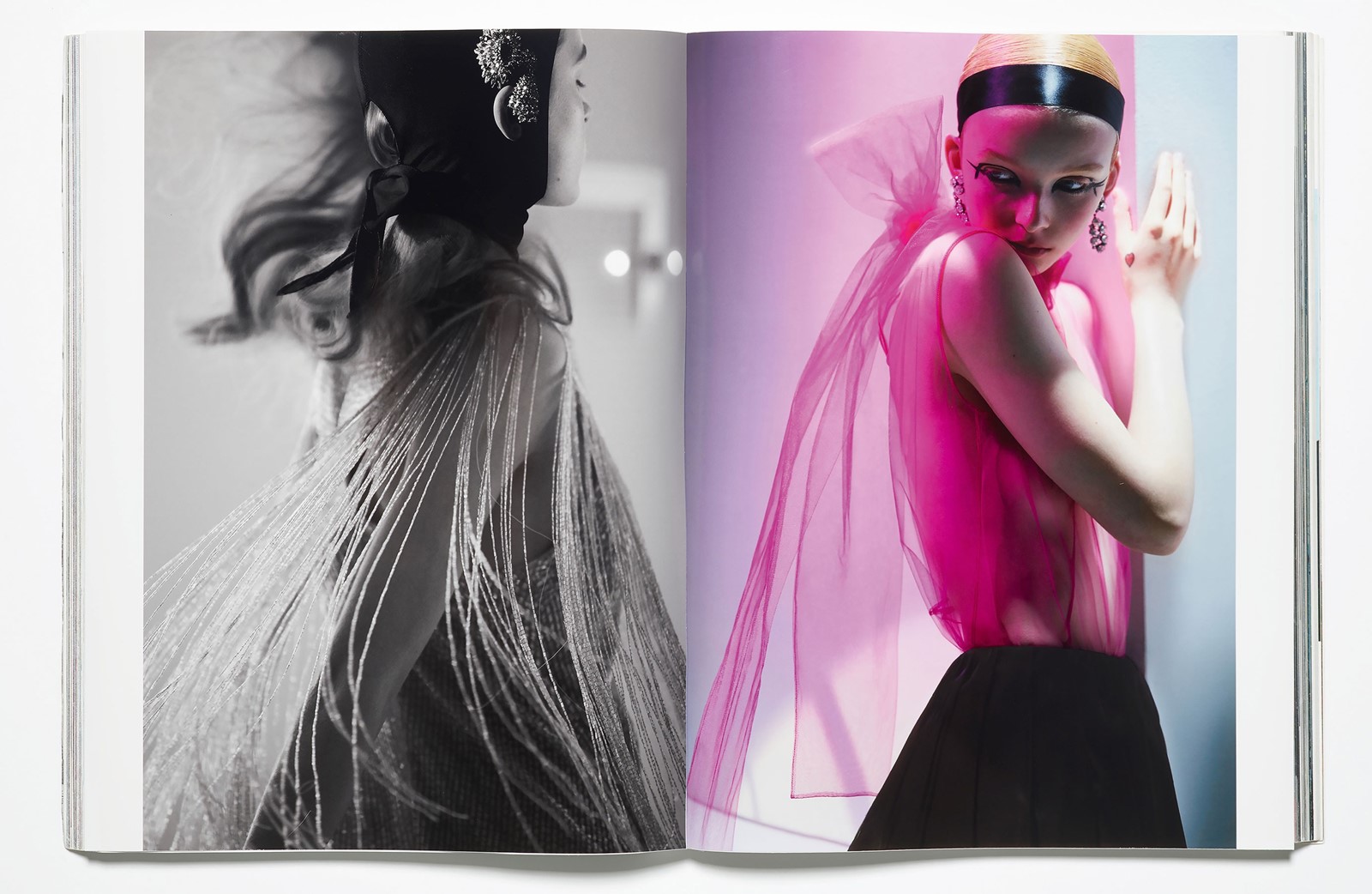

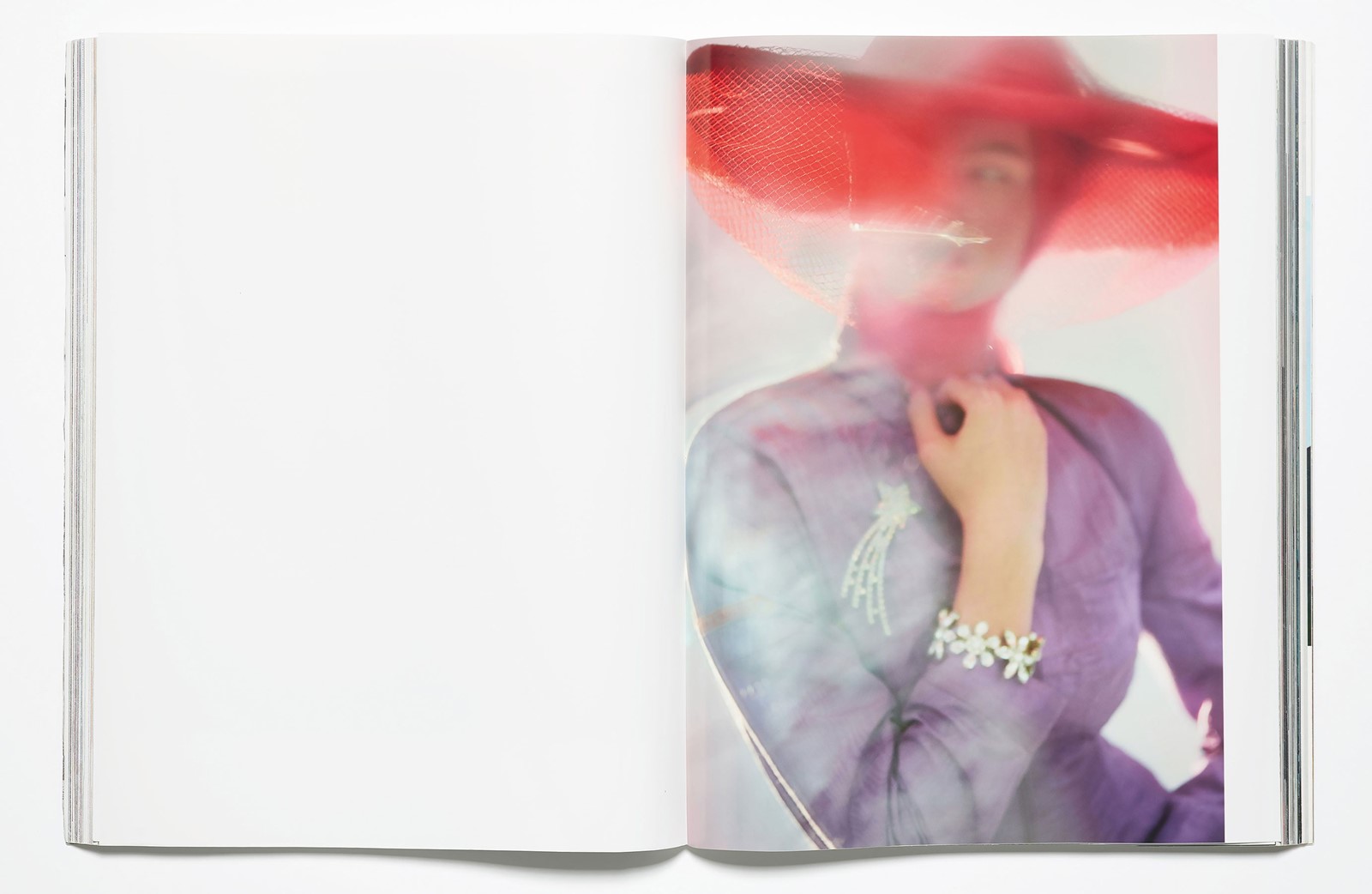

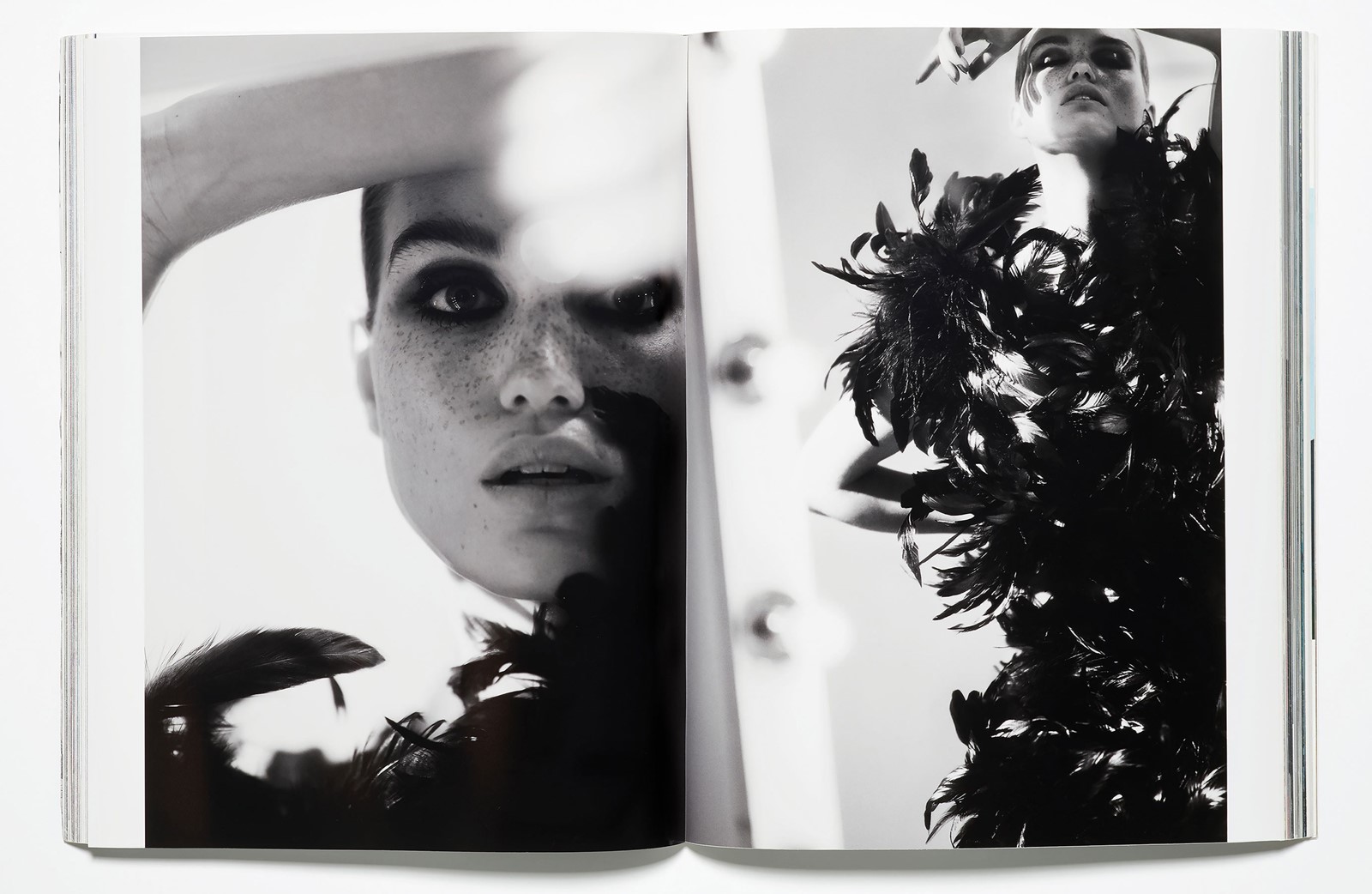

Hair: Sam McKnight at Premier Hair and Make-up using Hair By Sam McKnight. Make-up: Val Garland at Streeters. Models: Luna Bijl at Premier Models, Fatou Jobe at Silent Paris, Felice Noordhoff at Select Models and Lily Nova at IMG London. Casting: Noah Shelley at AM Casting. Set design: Andrew Tomlinson. Manicure: Ama Quashie at CLM Hair and Make-up using Gelish. Photographic assistants: Rob Rusling, Josie Hall, Tom Alexander, Olivier Barjolle and Georden West. Styling assistants: Molly Shillingford, Max Pugh and Jeffrey Thomson. Hair assistants: Fabio Petri and Jennifer Lil Buckley. Make-up assistants: Joey Choy and Francesca Etu-Menson. Set-design assistant: Tobias Blackmore. Image capture: Joe Colley at Passerine. Digital post-production: Mark Boyle at Epilogue Imaging. Production: SHOWstudio. Production assistant: Mariana Caldeira. Production runners: Georden West, Sophie Brunker and Eugene Herbet. Lighting: Direct.

This full story originally featured in the Autumn/Winter 2018 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale internationally now.