British filmmaker Jenn Nkiru’s new film Black to Techno explores techno’s relationship to Detroit’s black music scene

2018 was a whirlwind year for British-Nigerian filmmaker Jenn Nkiru. She directed music videos for Neneh Cherry and jazz musician Kamasi Washington; in June, the video for Beyoncé and Jay-Z’s Apeshit (under their duo, The Carters) was released, which she worked on alongside director Ricky Saiz.

Prior to that, Nkiru debuted the arresting short Rebirth is Necessary – a powerful exploration of the black experience which encompassed archive footage of Sun Ra and the Black Panthers – on NOWNESS. The expressionistic documentary is a forebear to her latest project – Black to Techno, part of Frieze and Gucci’s short film series, Second Summer of Love, following Josh Blaaberg and Jeremy Deller.

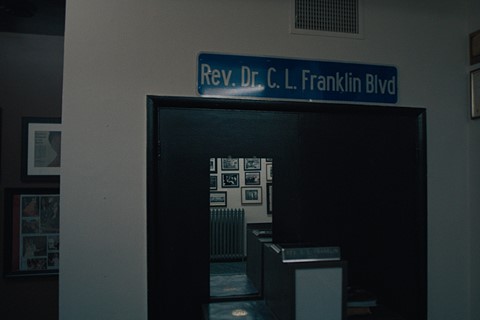

The short, which debuted at Frieze Los Angeles, explores the origins of Detroit’s techno culture, linking the city’s once-thriving automobile industry with the mechanical sound which subsequently exploded onto dancefloors the world over. Part history lesson, part visual art project, Black to Techno unearths a major aspect of techno music that is often forgotten: its foundation as a historically black sound.

“My hope is that all individuals with some level of curiosity can come into these things and see aspects of themselves, or at least be curious about things they don’t know,” Nkiru explains of the film, which collates archival film clips, samples, and interviews with Detroit’s music legends.

As such, the film defies categorisation – though it has elements of a documentary, it is more like a trail of consciousness, illuminating the inner workings of Nkiru’s mind, and her background in music videos, and visual art. Black to Techno at once catalogues an important part of music history, while serving as a work of art itself – partly a response to her own education, at the historically African-American Howard University, where films could be “very educational, but boring to watch”.

“It’s like, how do we hide this medicine in ice cream? How do we present this in a way that people are interested in and can vibe with, but can also get in their knowledge? I don’t think knowledge has to feel like a painful thing,” she says.

Nkiru has termed her amalgamation of artifacts – of archival film, music and speech – as “cosmic archaeology,” which she defines as unearthing bits of information she finds and putting them back together. The question she hopes the resulting film will answer is simple: “How can we become more familiar with ideas that are from our past?”

“I believe that there is a memory of, but it needs awakening,” she says. “These things manifest themselves as a trigger for latent memories inward and self-discovery. Archaeology is used as a process to get to a space of awakening.”

Just as important as techno’s roots is its intersectionality within a wider context. Nkiru’s homage to the genre attempts “to bridge the link between institutions – the scholastic academy – pop culture, and art. That’s my trifecta. Music is my first language and my first obsession. I have this want to create generational links. Things are getting lost and I have this self-imposed need to make sure things are getting passed down,” she says.

She shows this by filming three generations of legendary female techno DJs – Stacey Hotwaxx, Minx, and DJ Holographic – playing records side by side in an automobile factory, while assembly-line workers build cars behind them.

As for Nkiru’s connection to techno, she says, “I had been thinking about afrofuturism and the overlaps to techno. I describe techno as a resulting sound. It’s a result of its environment, the geopolitical landscape, its legacy, its history, its geography all go into its making. It could not be created anywhere else. I want to look at techno not just as a sonic gesture, but as a geopolitical, anthropological gesture.”