With a new documentary Penny Slinger – Out of the Shadows just out, Slinger talks to AnOther about its making and the changing face of feminism

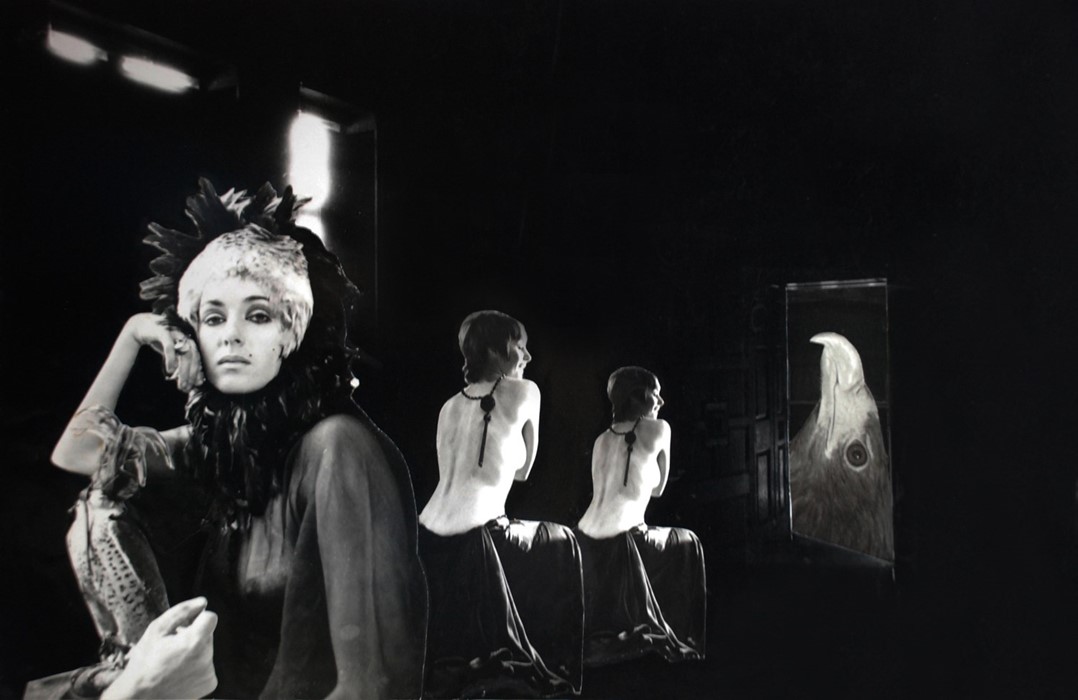

The British artist Penny Slinger is undoubtedly one of the most radical artists of the 20th and 21st centuries. She took the language of surrealism and put her own, very personal spin on it, using herself as her own muse to challenge and re-dress what was traditionally a very male dominated sphere. Throughout the 60s and 70s, she created myriad collages, films and sculptures – with collaborators including filmmakers Peter Whitehead and Jack Bond and feminist playwright Jane Arden – that plumbed the depths of the female psyche, from the spiritual to the sexual, the psychological to the philosophical and beyond. Her liberated, licentious and visually arresting work took the art world by storm, with Rolling Stone magazine writing of her first book, 50% The Visible Woman (1971), “this is a major work – surely to become as ubiquitous as Sergeant Pepper in the culture”. By the late 70s however, Slinger had mysteriously “disappeared”, only reemerging to reclaim her rightful position in contemporary art history some 30 years later when she was included in the exhibitions Angels of Anarchy: Women Artists and Surrealism (2012) at Manchester Art Gallery and The Dark Monarch (2014) at Tate St Ives.

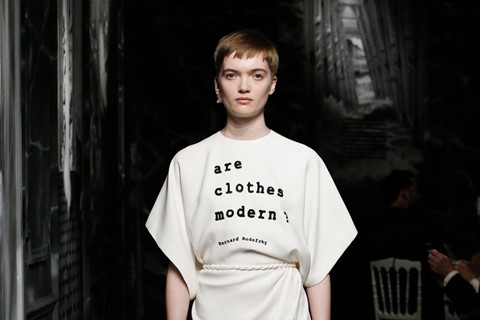

This year, however, is truly Slinger’s year: a new exhibition celebrating her tantric art of the mid-70s just opened at Richard Saltoun gallery, while Maria Grazia Chiuri called upon Slinger to create the hypnotic scenography that formed the backdrop for Dior’s A/W19 Haute Couture show this past weekend. The collection’s final look – a striking house-shaped dress in gold – was inspired by Slinger’s series Doll Houses. Meanwhile a brilliant new documentary by Richard Kovitch, titled Penny Slinger – Out of the Shadows, has just hit cinemas, charting the artist’s formative years, leading up to the realisation of her seminal 1977 work An Exorcism, as well as her subsequent withdrawal from and return to the art world. Here, in celebration of the film’s release, Slinger sits down with AnOther to discuss its making, the changing shape of feminism and her continued fight for freedom of expression as a woman in her wisdom years.

“I know a lot of people who’ve had documentaries made of them, who were disappointed in them and felt that they hadn’t done the right thing. I myself have a bit of an aversion to talking head documentaries, but this film I feel is a standalone work of art in its own right. I feel very fortunate because Richard worked very considerately with me all the way through, and Zoe, who did the editing, put the film together in a collage kind of way. Then Psychological Strategy Board did this really edgy soundtrack for it. I feel we have this very experiential piece of filming here, and I also appreciate that Richard really understands the cultural milieu that my work came out of.

“All this formed while I was still a student at Chelsea College of Art. When I had to do my thesis, I was looking through the whole history of art, studying everything, and I felt so much that women featured all throughout art, but generally as the muse. They’re portrayed so often – the naked feminine form is a highly valued feature of artwork across the ages and throughout cultures – and yet there were so few women artists. I thought that that, combined with my experience of being a student coming up in an art world that was still very much a man’s world, was something that needed to be addressed and re-dressed.

“I did my thesis on Max Ernst, because I’d fallen in love with his collage books, Une Semaine de Bonté and La Femme 100 Têtes. I wrote an in-depth piece about it for my thesis and made a little animated film as a tribute, and then I created my book [of collages and poems] 50% The Visible Woman to say: ‘This is how you’ve inspired me and this is how I want to treat this now.’ I wanted to use the tools of surrealism and collage – but rendered from my perspective in photographic collage, rather than the old engravings that Ernst was using – to try to explore the feminine psyche and lay it bare. I wanted the work to ask, How is woman seen? How do other people view her? How does she view herself? The title I took from those anatomical models with the skin visible on one side and peeled away, to show the inner organs, on the other.

“I wanted my work to peel away the layers of the seen world, to look inside and show the unseen world of a woman’s subconscious and her fantasies. I also thought it was about time to be my own muse – not just to rely on being seen by a male artist and interpreted through his lens. Let’s do the seeing ourselves as women and show not only the body but also what is really happening at all levels of consciousness. And collage is a wonderful medium because it allows you to bring together pieces of reality in a new way and shake things up a bit!

“I wasn’t quite in the normal run of what was coming up in feminism at that time because I felt that women shouldn’t just be viewed on an equal par to men, or that we should be more like men – I wanted to liberate this whole package of who a woman is. I wanted her qualities to be valued on an equal power, and I wanted that to include all the sensuality and sexuality that is our birth right, not to have those elements pushed aside in order to claim our rights. And many feminists criticised my work for being too sexual back then. I feel much more able to claim a position of being a femininst now, because the term has broadened over the decades to include all the things I felt it needed to include.

“When I did my first exhibition in New York, I thought that it would be somewhere where they really get it and understand what I was doing. Unfortunately many of the people who came to the exhibition were rich and powerful men, three in particular who could have bought most of the exhibition but ended up not buying anything because I wouldn’t sleep with them and I was frankly totally disgusted by this. They thought: ‘Your art is erotic so you must be.’ And that was, in a way, the last straw for me in my relationship to the art world at that time. I felt I was being misunderstood – I wasn’t doing these things as some kind of come on, but because it was important to me and my psyche and for the liberation of psyches in general – not just women’s. After that I moved to the Caribbean for 15 years and exhibited my work there, outside of the mainstream fine art world.

“Coming back into that realm now has been wonderful actually. I always think, if you’re open to it, life will bring you what you need at the time you need it. I’d had my time in the Caribbean and I had been living in northern California for 20 odd years, when I realised that I’d been more or less forgotten by the fine art world – because I hadn’t been there. I felt really jipped by that. I’d always felt that I was meant to be a very major artist and purveyor of consciousness, but I’d been cut out. So when the opportunity came for me to get back in – through Anthony Penrose, who gave the pieces to the Angels of Anarchy show, and Linder [Sterling] who helped connect the dots for my inclusion in the Dark Monarch show – I was happy to be able to return to the UK and connect with people again. Then Riflemaker asked to show my work after that and it snowballed. The timing has been really perfect for me because the art world is finally recognising the role of women artists and wanting to support it.

“I am now very actively trying to put into effect what I call the next bastion of feminism, which is surrounding ageism and the fact that women in particular, as they get older and are no longer seen as sexually magnetic creatures, are deemed irrelevant by society and cast aside. They don’t have the opportunity to bring their wealth of experience and accumulated wisdom back into the cultural melting pot. So – for a new body of work which I’m yet to show – I’m using my own body as my muse once again to show all the different facets that I represent as now as a woman in her wisdom years. I am trying to bust through that glass ceiling that says that when we get older we don’t matter any more. I think we matter all the more and that beauty is more than skin deep. It’s something that matures like a fine wine and I feel I have much more to offer now than I ever have before in terms of my experience in life.”

Penny Slinger – Out of the Shadows is out now, see here for screening details.