Andrew Bolton is probably the most famous fashion curator in the world: leading The Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Costume Institute since 2015, the 52-year-old visionary has staged some of the most culturally significant, talked-about – and, importantly, visited – fashion exhibits of the 21st century. In person, he is self-effacing – on his role at the Met Gala, the Anna Wintour-helmed event which raises funds for his yearly exhibits and attracts countless international celebrities, Bolton says “I’m totally invisible”.

We meet in London, at Sarabande, The Lee Alexander McQueen Foundation in east London, of which he is a patron. Bolton shakes hands with the young artists in residence – Sarabande provides studio spaces to emerging artists at highly subsidised rates, as well as mentoring and university scholarship opportunities – and peers around their studios in horn-rimmed glasses with a genuine sense of curiosity. He is dressed head-to-toe in his usual uniform of clothes by New York designer Thom Browne, his longterm partner, a nod to his self-admitted immersion in American culture. The Britain-born Bolton moved to New York in 2002 to work at The Met, poached from the V&A museum. “I feel more of an immigrant going back to England than I ever do here,” he once told The New York Times, speaking of the city he now calls home.

But Bolton’s roots are planted miles away from Manhattan. Growing up in Blackburn, Lancashire in the north of England, the son of a stay-at-home mother and a father who worked in newspaper production, he first became interested in fashion through New Romantic music. “There were so many subcultural movements in the 1970s and 1980s, so my entrée into fashion was through music and style magazines like i-D, The Face, Blitz, and seeing Vivienne Westwood and John Galliano’s graduate collections,” he says. “There just was so much bravery around fashion then.” But, rather than running away to London to party at Kinky Gerlinky or the Blitz Club, by the age of 17 Bolton had his sights set on a career in curation, and enrolled in an undergraduate course in anthropology at the University of East Anglia in Norwich. “It’s interesting because anthropology is really about the study of people and their behaviour. That is so much a part of fashion,” he says. “I tend to approach themes through an anthropological lens first and foremost, then I use the garments to tell my story.”

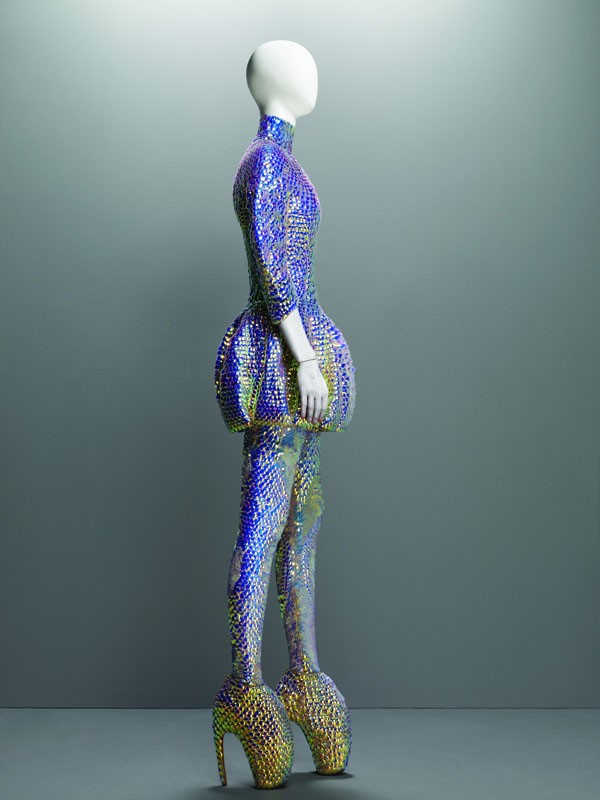

Indeed, storytelling is at the heart of Bolton’s curatorial vision, and the subject matter that he chooses to investigate in his exhibitions at The Met draw audiences with compelling and timely themes. The proof is in the hundreds of thousands of visitors that flock to shows like Alexander McQueen: Savage Beauty (2011), Rei Kawakubo/Comme des Garçons: Art of the In-Between (2017) and Heavenly Bodies: Fashion and the Catholic Imagination (2018) – which holds the title of the most-visited fashion exhibition in The Met’s history – each year.

“It’s interesting because anthropology is really about the study of people and their behaviour. That is so much part of fashion” – Andrew Bolton

Of course, the buzz surrounding the annual Met Gala has helped to raise awareness and funding for the exhibits, and Bolton works closely with American Vogue editor-in-chief Anna Wintour on getting the dress code right in accordance with the exhibition’s theme. But otherwise, his involvement in the Gala is very much behind the scenes. “It’s church and state,” says Bolton. “Anna is ‘hands-off’ for the exhibition, and I’m ‘hands-off’ the gala which is great. Anna is extraordinary – she gets the guestlist just right every year. When I’m there, at the party, I’m totally invisible. You’re in this room with some of the most famous people in the world, and you’re a nobody. It reminds me of Mr Cellophane, that song from the musical Chicago. To me, the Gala is another exercise in people watching.”

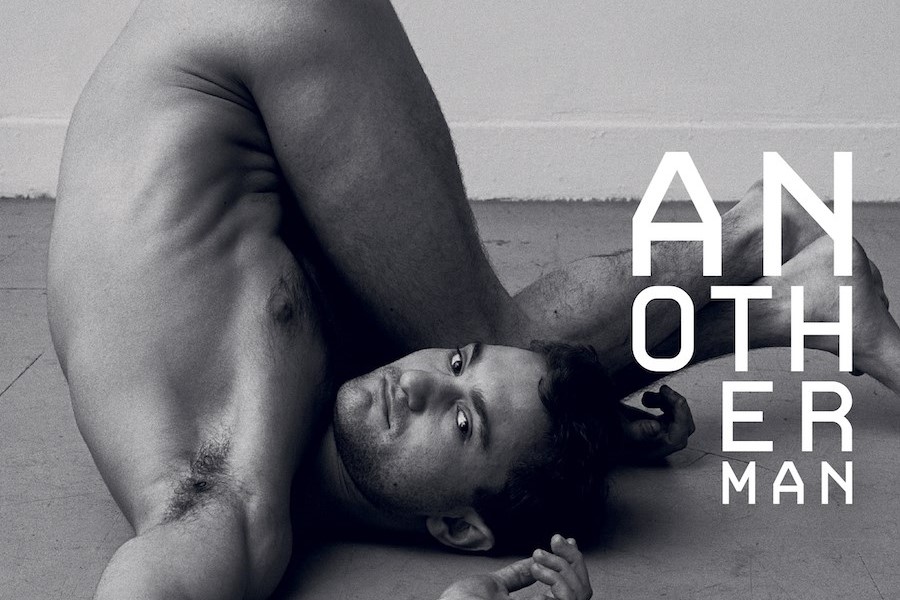

The latest Gala, themed around ‘camp’, coincided with the current exhibition realised by Bolton at The Met: Camp: Notes on Fashion. “Camp is so political, and it does emerge at moments of polarisation, moments of high conservatism,” he says. “It’s what I grew up with, in the 1980s, with Reagan and Thatcher. Even though it’s become more mainstream, it’s never lost its subversive capacity, so I felt it was really timely. We always try to do an exhibition that captures the zeitgeist so that’s the reason why we chose the theme for 2019.” Although, Bolton began laying down the groundwork for Camp three years ago, while he was working with Rei Kawakubo on Art of the In-Between.

Here, Bolton began revisiting Susan Sontag’s essays Notes on Camp, which formed the basis for the current show, and Against Interpretation, which he read as a tool for chiselling away at the almost impenetrable mind of Kawakubo. “Rei insisted that her work shouldn’t be interpreted, which is exactly what my job is as a curator,” he says. “So there was a lot of push and pull. She was impenetrable but she’s also more vulnerable than you think. There was a moment when I asked for one particular piece from a collection and she said: ‘Andrew, if you displayed this it would be like me going in the streets with no clothes on’. Part of working with a designer is to respect their vulnerabilities and insecurities.”

Such sensitivity was integral to the staging of Savage Beauty in 2011, too. A celebration of Alexander McQueen’s life and work – assembled just under a year after the designer took his own life – there was a bureaucratic concern that it would be considered “funeral chasing”, as Bolton puts it. Yet, the curator persisted and avoided artifice by working collaboratively with those closest to McQueen, while meticulously considering the themes present within his incomplete archive. The result was a powerful eulogy. “It was a way of people dealing with their grief,” says Bolton. “It was never intended to be a retrospective. It was always intended to be an essay on an aspect of Lee’s work.”

In the 2016 documentary The First Monday in May, director Andrew Rossi follows Bolton and Wintour in the lead up to the previous year’s exhibition and Gala, China: Through the Looking Glass. In the film, the pressure to create a show that would live up to the acclaim of Savage Beauty, weighs on Bolton. Rossi also very clearly shows him as the beating, creative heart of The Costume Institute, with Wintour taking care of the business side of things. But despite this, Bolton still can’t quite believe the dreams he harboured since a teenager living in the north of England, have actually come true. “My overwhelming emotion was being intimidated by the museum and the other curators. I felt like I was going to get caught out,” Bolton says in the documentary, of his imposter syndrome.

Three years on, and four more blockbuster exhibitions under his belt, Andrew Bolton’s attitude hasn’t changed. While he continues to encourage cultural and historical conversations about fashion among celebrities, academics and the general public alike, Bolton is unable to reveal anything to me about next year’s show. Although I suspect if he could, he would be more than willing to.

Camp: Notes on Fashion is at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, until September 8, 2019.