In New York this week, Helen Kirkum, Alex Nash and Shun Hirose celebrated their takes on the Campus 80s sneaker. We speak to the three designers about working with adidas’ MakerLab

On a recent afternoon in New York, three footwear designers gathered in an unassuming warehouse in an area of Brooklyn’s Greenpoint neighbourhood still largely un-gentrified (on the same street you will find Lucky’s Real Tomatoes, a tinned tomato factory; opposite, Acme Smoked Fish Corporation). Unassuming from the outside, at least: inside is a veritable Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory for sports- and sneakerheads, adidas’ Brooklyn Creator Farm, where the sportswear behemoth dreams up the future.

The three designers – Helen Kirkum and Alex Nash, both from London, and Shun Hirose, from Tokyo – are not employees of adidas. Kirkum, who is based in Hackney, makes de- and reconstructed sneakers (each is entirely bespoke, and are created on a project-by-project basis); Hirose, under the name Recouture, makes one-of-kind customised footwear, much of which involves a Frankenstinian process of swapping the soles of existing shoes; while Nash was one of the pioneers of the custom sneaker movement in the 1990s, known for melding sneakers with elements from traditional footwear (among them moccasins, and boat shoes). Yet, as of this week, each will have an adidas sneaker which bears their name, on sale to the world and thus forever immortalised in the brand’s vaunted archive.

It is the result of the latest iteration of adidas’ MakerLab, which, in its various guises, has opened up the creation process to people around the world, from world-class athletes to school children (adidas call it part of their “open-source” design policy, which is energised by collaborators and creative forces external to the company). Last January, for example, designers Priya Ahluwalia, Paolina Russo and Nicholas Daley worked with the MakerLab to create a series of custom adidas sneakers which were presented in a runway presentation in Paris; other MakerLabs have taken place in London and Shanghai. This latest chapter, though, marks the very first time a MakerLab creation will go on sale to the public.

“Who doesn’t want to have a stab at creating a shoe of their own?” says José Cabaço, adidas’ global creative concept and storytelling director, who likens the MakerLab to a “playground for grown-ups”. The problem, though, has been moving it on to something more than this: those who have taken part in the workshops previously are left at the end with just one shoe, a single protoype sneaker, which you cannot wear, and will never get made. “So with this, we wanted to take it from an exercise in style, an inside gathering, to allowing the people we brought in to go to market,” he says. “It is the difference between opening the door and the window into a process where you get to create and be inspired, and actually really giving something to the people who participate,” adds Tareq Nazlawy, senior director of digital strategy.

And so marked the beginning of a process which from advent to final sneaker was a matter of months, the creation process itself just 10 days, taking Kirkum, Hirose and Nash from their respective studios to adidas’ headquarters in Herzogenaurach, to Vietnam, where many of adidas’ sneakers are made (the usual process of creating a new sneaker can take from six months to two years). Each was tasked with reinterpreting the Campus 80s sneaker – first created in the 1970s as ‘Tournament’ and renamed ‘Campus’ in the 1980s – with few holds barred on what the final result could be. For the designers, who noted the ubiquity of adidas growing up (“in the 90s you always saw the three stripes on the street – my sister had adidas tracksuits and I was jealous,” says Kirkum), it was a proposition both thrilling and terrifying.

“We are putting our names to the shoe, our faces to the shoe,” says Nash. “It’s daunting – when I think about custom shoes that I’m gonna create, I spend weeks, you know, going to bed and constructing the shoe in my mind. The short deadline kind of flipped it all upside down.” And for Nash, there was extra pressure, too: the MakerLab project marks his return to the footwear industry, having taken time off to concentrate on other projects. “I’m trying to honour myself and, you know, I want more work from this. I just want more chances to express my creativity,” he says. When asked how it feels that his shoe will exist in the adidas archive for decades – perhaps even centuries – to come, he is still incredulous. “If I ever go to Herzo I’m going to hit up the archive and ask for my shoe,” he says. “I want them to prove it to me.”

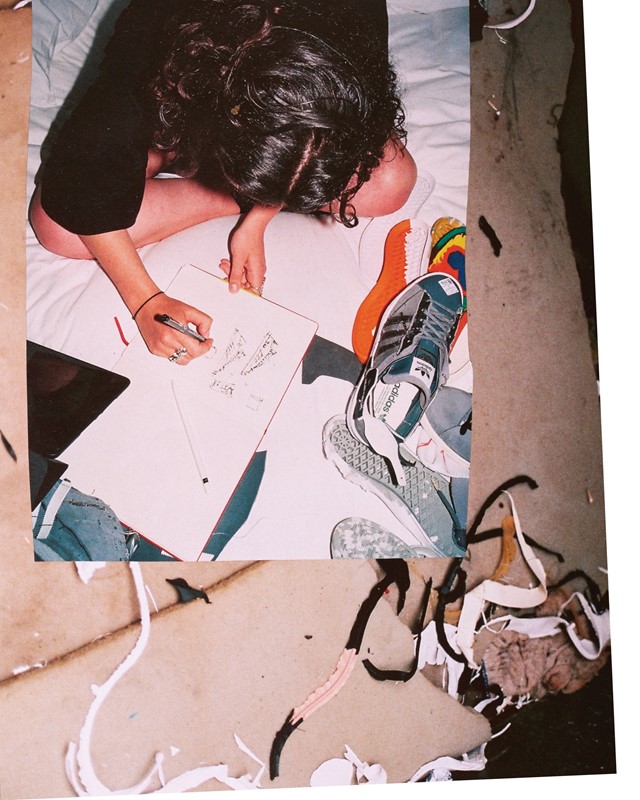

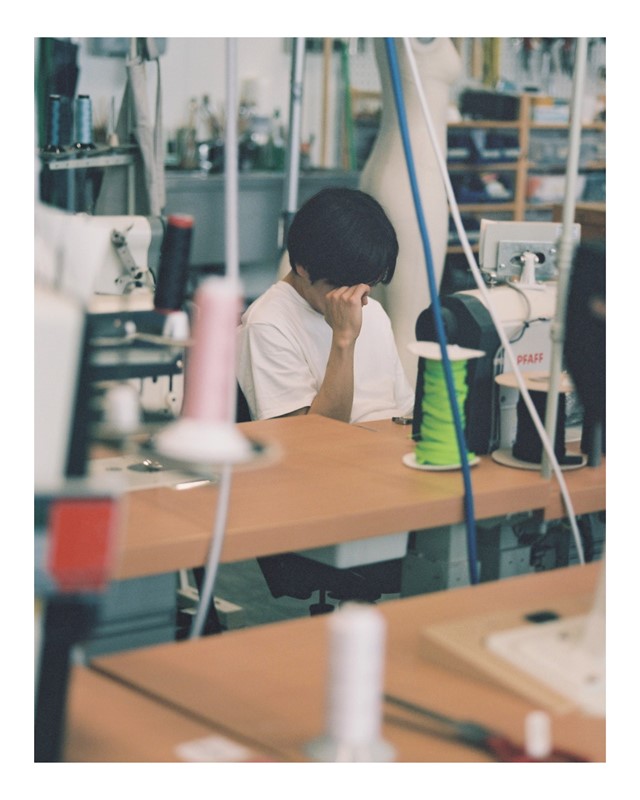

Fortunately, they had each other: amid various meltdowns (some of which occurred just hours before their sneakers hit the production line), the trio emerge with the type of camaraderie you only get when you’ve really been through something together. “It was very intense for all of us, even just being around the same people for like two weeks is a lot in itself,” says Kirkum. “But everyone was so friendly, so supportive. I teach quite a lot, and whenever I teach students one of the main things that I always say is that you have to be nice to people because if you’re not, people aren’t going to want to work with you.” Even Hirose, who does not speak English and communicates through a translator, found that the language of sneakers is largely universal – video footage shows the three designers round-tabling their designs with the type of honesty usually only possible when you have been around somebody for years.

“This project has given me an opportunity to come out of my shell,” says Hirose, who is quieter than Kirkum and Nash (Cabaço said of the three he was the most thoughtful, and always “knew exactly what he wanted”). “My passport was expired before I came here, I hadn’t left the country for five years. I’ve become more adventurous. My life has been transformed meeting these people.”

An evening later, at a different warehouse in Greenpoint, the designers gather once again – this time, accompanied by various people from the industry, and friends and well-wishers – to watch the accompanying documentary, which intimately records the process from sketch to sneaker. Afterwards, a clock appears on the screen, counting down the minutes until the sneakers – in editions of 333 pairs – go on sale on StockX, a sneaker retail site which allows consumers to purchase in a system based on stock market IPO (buyers place bids, sellers place ‘asks’ – when bid and ask match, the shoes are sold). The designers are emotional: “I just hope someone wants to buy my shoe,” says Kirkum.

An hour or so later, Kirkum is outside, on her phone. The StockX website is whirring with bids. “500 people have already bidded on my shoe,” she says. Scott Cutler, the CEO of StockX, sidles up next to her. “Look at this text message,” he says. It is from his wife: there is a screenshot of Kirkum’s trainers – she wants to buy them. Is the pressure off? “Yes,” she laughs. “I can have a drink now.”

Over the next few days, the bids rise to the thousands for each designer. But it’s hardly the point. “If I think about my Instagram, some of the better moments when people send me a DM with something that they’ve made and they’re like ‘ah, I was inspired by you and I made this’,” Kirkum had said the day previously. “Hopefully this will continue to grow. I think it shows you can put your own spin on things; your own stamp. It shows that this new way of working is actually possible.”

All three Campus 80s MakerLab pairs are available until 9pm EST, on StockX.