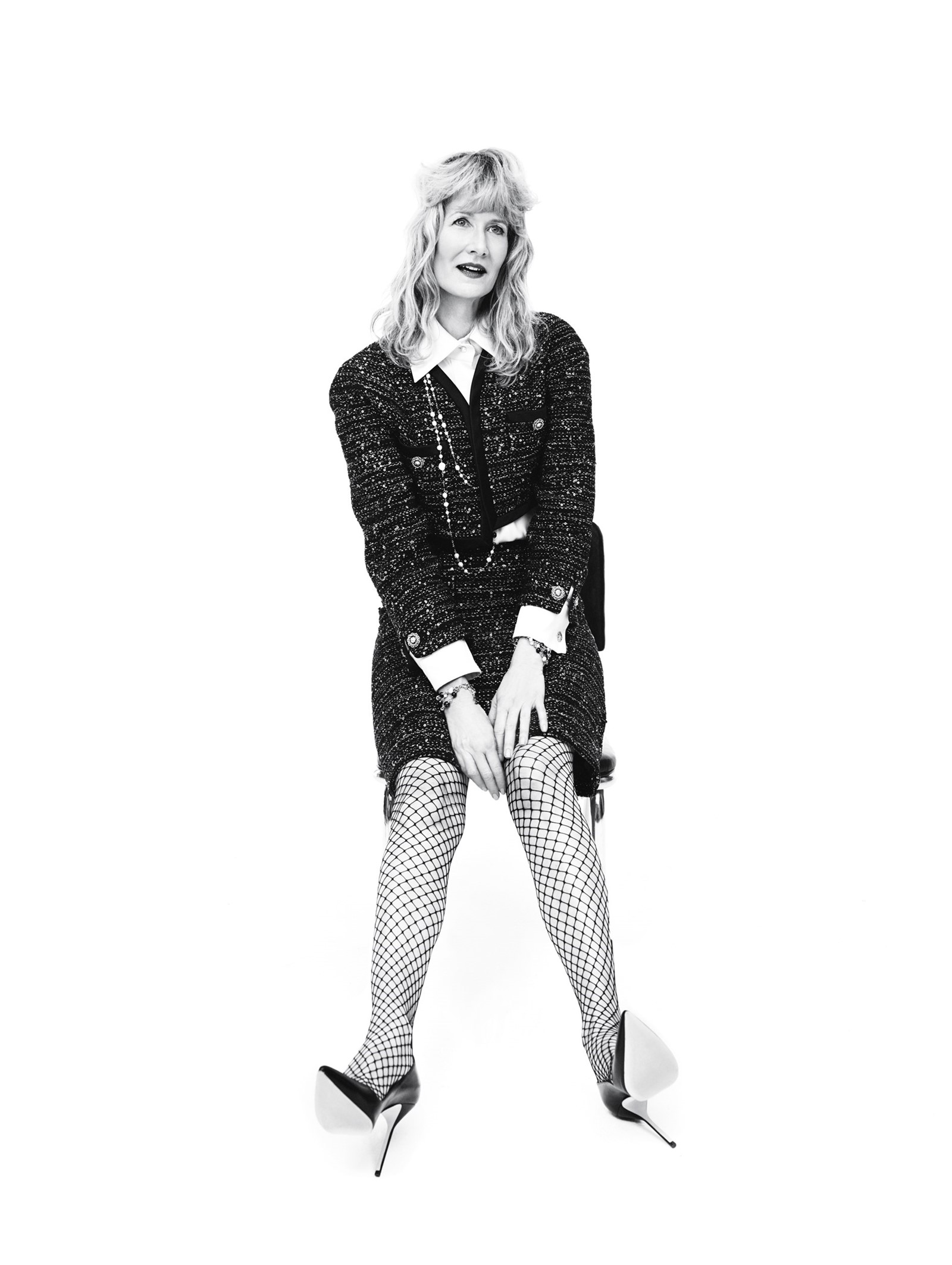

The term ‘Hollywood royalty’ may have been invented for Laura Dern. She and her actor parents – Bruce Dern and Diane Ladd – have neighbouring stars on the Walk of Fame, the first family to be collectively embedded into that celebrated boulevard. On-set even before birth, she has gone on to establish herself as one of the foremost actors of our era: she has worked with Martin Scorsese, Steven Spielberg, Jonathan Demme, Paul Thomas Anderson, Clint Eastwood, Robert Altman and, of course, David Lynch, all enamoured by her extraordinary talent, famous wit and tumult of feeling both on-screen and off. With a 2020 Oscar nod and a Golden Globe for her acclaimed turn in Noah Baumbach’s searing Marriage Story, she is an actor at the height of her power.

Laura Dern would have been the size of a poppy seed on the set of 1966 exploitation flick The Wild Angels, an orb of cells flashing to the sound of her mother’s heartbeat. Her future parents, Diane Ladd and Bruce Dern, were burning rubber around Coachella as leathered-up bikers alongside Peter Fonda, Nancy Sinatra and a chapter of the Hells Angels. All speed, swastikas and surf’s-up score, the moral-free movie by grindhouse auteur Roger Corman filled drive-ins across the US that year as the nation’s youth answered its countercultural howl. Which is all to say that Laura Dern has never not been in the movies. As a week-old newborn she slept in the drawer of a motel room in the Mojave Desert while her dad shot a Western with Charlton Heston. Aged five, she watched her father’s decapitated head bounce down a staircase in the camp Bette Davis psycho-thriller Hush ... Hush, Sweet Charlotte – it was the first time she had seen him on-screen. At seven, Dern made her own debut. You can spot her eating a banana ice-cream cone in the diner of Martin Scorsese’s 1974 drama Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore, while her mother plays a hard-eyed Tucson waitress. That day, Dern ate her way through 19 ice creams (in the 19 takes it took to nail the scene) with such stoic professionalism Scorsese told Ladd her daughter was destined to become an actress. Today, Scorsese is just one of a constellation of directors – Steven Spielberg, Clint Eastwood, Paul Thomas Anderson, Robert Altman, Peter Bogdanovich, Jonathan Demme, David Lynch – who have revelled in Dern’s expansive empathy for messy, transgressive characters whose impulses wrestle their way across her face like jailed spirits.

Much has been made of those elastic features – in recent years the internet has fallen deeply in love with the existential anguish of Dern’s “cry face”, first seen in Lynch’s Blue Velvet, when pastel cardigan-wearing Sandy is confronted with the pitch-black underside of her milk-and-cookies lumber town. Raf Simons printed images of it across garments in his Autumn/Winter 2019 collection, as though they were posters pinned to a besotted teenager’s bedroom wall. If the term ‘fearless’ is applied to any actress who allows herself an unflattering angle or an unpalatable character, Dern ups those stakes by an exhilarating stretch. Whether playing a homeless huff addict or a woman light years past the verge of a nervous breakdown, she remorselessly draws out our compassion for the misfits and the misunderstood, women whose tumult of feeling can’t help but burst out at the seams. “I love what I do, I love falling in love with these outrageously complicated characters,” Dern says when we meet at a hotel near Central Park on a silvery New York afternoon. “They’re often women struggling to find their own voices. They’re women in completely different positions and moments in their lives, who don’t feel that the world has given them room to have a voice or opinion, or to matter. And I think that is a female plight.”

In person Dern is warm and passionately committed – to her political causes and her screen collaborators. The more fiercely she feels, the more animated her gestures, a habit that won her the tagline “the mom who talks with her hands” at her son’s primary school. Her voice has a scratch in it today from back-to-back meetings, and her phone is emitting regular beeps from stylists and assistants until she silences it, so the hotel phone starts ringing instead. The internet would have you believe we’re in the swirling eye of the Dernaissance, a hashtag that originated sometime around the arrival of The Monterey Five in 2017. As wealthy helicopter mom Renata Klein in HBO’s runaway success Big Little Lies, Dern was the raw nerve in jewelled Gucci running shoes who stole every scene: she had a seat in the boardroom, a vertiginous, glass, cliff-side home and a jaw permanently clenched against a perfect tangerine sunset. Somewhere around the moment she accessorised a scarlet wrap gown and thigh-high Louboutins with a dumbbell, she became not only the raging id of the show but the cherished lightning rod for all righteous female anger in the Time’s Up era, not to mention a Halloween costume and the subject of a proliferation of memes, her talent for imaginative expletives rivalled only by her one-time co-star the late Dennis Hopper. When Dern collected a Golden Globe for her performance in 2018, she used the platform to deliver some hard truths to Hollywood in its reckoning with the explosive #MeToo revelations: “Many of us were taught not to tattle,” she said. “It was a culture of silencing, and that was normalised ... May we teach our children that speaking out without the fear of retribution is our culture’s new North Star.” She had brought the activist Mónica Ramirez as her guest to the awards ceremony, and she continues to embody everything Trump loathes about the blue state of California, liberal Hollywood running through her veins: she and her parents have neighbouring stars on the Walk of Fame, the first family to be collectively embedded into the pavement of Hollywood Boulevard.

“I love what I do, I love falling in love with these outrageously complicated characters... They’re women in completely different positions and moments in their lives, who don’t feel that the world has given them room to have a voice or opinion, or to matter. And I think that is a female plight” – Laura Dern

Dig into her family tree and there are some equally high achievers. Born in Mississippi, Diane Ladd is a cousin of the playwright of melancholy heroines and gin-cocktail lunches Tennessee Williams. Bruce Dern hails from an erudite family from the shores of Lake Michigan – his relatives include a grandfather who was Franklin D Roosevelt’s secretary of war, and the modernist poet Archibald MacLeish. Both Dern’s parents honed their craft in The Actors Studio and cut their teeth on the stage, which was also where they met: Ladd was performing in an off-Broadway production of Williams’ Orpheus Descending when her co-star became ill. Bruce Dern stepped in as understudy and they were married a few months later. The pair must have made a formidable double act, but the marriage didn’t last. They suffered the unbearable loss of a baby daughter in a drowning accident before Laura was born in 1967; she was just two when they divorced. While her father moved out to the then bohemian shores of Malibu, Dern was brought up by her mother and grandmother, first in Santa Monica and, later, Beverly Hills. It wasn’t unusual to encounter the likes of Gregory Peck, Marlon Brando and Jack Nicholson at home, although it was her mother’s formidable clan of girlfriends – all unconventional, politically outspoken and absolutely devoted to their art – that loomed large in her early years. “In my mom’s house it was always a gaggle of amazing women,” she says. “My godmother was Shelley Winters. There was Maureen Stapleton, who was in a lot of Billy Wilder movies, Ellen Burstyn and Gena Rowlands. I mean, I was around some badasses.” She has a story of attending the 1978 premiere of Superman with Marlon Brando and her tough-talking, frequently married godmother: under a shower of flashbulbs, Winters stepped onto the red carpet in jeans, sneakers and a grey sweatshirt, a full-length mink coat slung around her shoulders. It crystallised in Dern’s mind the kind of woman she wanted to be.

By nine, she was already riding her bike to drama classes. “I was kind of a weirdo,” she says. “My friends had posters of the cute boy from the band, my wall had Barbara Stanwyck, Katharine Hepburn, Édith Piaf and Lucille Ball. Those were my first female icons. And they all make sense in terms of what I’ve gotten to do, but also what I’ve longed to do and what’s inspired me.” Despite the family pedigree, Ladd wasn’t sold on her daughter joining their ranks – at 11, Dern had to persuade a family friend to drive her to a clandestine meeting with an agent. She stuck a few more years on her age to audition for a role in the dark cult gem Foxes (1980), the tale of four wayward teens left by their dysfunctional parents to range unsupervised across the wastelands of LA on a diet of Coke and Twinkies, Quaaludes and heroin. Starring Jodie Foster and The Runaways’ shadow-eyed, rail-thin Cherie Currie (in Currie’s case, art was reflecting life all too closely), it was shot along a rackety Hollywood Boulevard to a shimmering Giorgio Moroder score. Dern shows up in the thick of an unruly house party in the Hills, faux-knowingly discussing the merits of various types of birth control – she was 12, and remembers feeling a lot less sure of herself than the world-weary miniature adult she was playing. But then, maybe that was the point. “I was so shy,” she says. “I was fierce about politics, and I was shy in every other area. And then, as an actor, I started to feel how comfortable I was on a set in front of a camera, collaborating with a director. That part of me that was uncomfortable in my own skin and worried about what other people thought was completely gone when I was acting. I think that’s why I fell so in love with it.”

The news of her next role was probably even less welcome to her mother: Ladies and Gentlemen, the Fabulous Stains was the story of an all-girl punk band stewing in a bleak Pennsylvanian factory town who lunge at the chance to escape on a shoestring tour to California. A long-bootlegged riot grrrl oddity, it reportedly inspired both Courtney Love and Bikini Kill (“I’m perfect, but nobody in this shithole gets me because I don’t put out,” says 15-year-old Diane Lane as the band’s frontwoman). Spare a twinge of sympathy for Dern’s mother – her daughter celebrated her 13th birthday on a cramped tour bus with co-stars who included two Sex Pistols, Paul Simonon of The Clash and Ray Winstone. On-screen, there are drunken fights and drug overdoses in filthy backstage toilets. Behind the scenes, the stories weren’t much more wholesome. “I saw a lot,” Dern remembers, “but I was really uninterested in drugs. I was really scared by them. I knew addicts at a young age and there was nothing sexy or cool about that, at all. I think if you see drugs and alcohol very young, it’s a great cautionary tale. I felt like my rebellion was to become my own artist, and I knew that if I became addicted to something, that was going to keep me from the place I wanted to get. So that’s where I put my energy.”

Dern was attending the elite Buckley School in the Valley at the time, its manicured campus peopled with the children of celebrities and celebrity children. Other notable alumni from her era include Bret Easton Ellis, though Dern sounds wholly unlike the infinitely bored, dead-eyed casualties conjured by that provocative author in his debut novel, Less Than Zero. “I was raised very strictly by my mom and my Southern grandmother. There was no rebelling at home,” she says. “My mom really forced me to stay at school. I had to be on one team at least, I had to be in student government, I had to get As and Bs, and then I could be acting. So it wasn’t easy, which was really smart of her.” By early adolescence Dern had almost reached her full 5ft 10in, despite trying to contort herself closer to her classmates’ more diminutive heights. “For sure it affected me,” she says now. “I didn’t fit in at school because that trait was geeky and awkward. But then I went to work and that trait was womanly. So I think, in terms of boys and men, it was confusing – not getting attention from any boy, but getting lots of attention from men at way too young an age.” That sticky time of transition made her devastatingly perfect for her first starring role, in 1985’s Smooth Talk, based on a chilling Joyce Carol Oates short story. A troubled teen with pinballing hormones tearing around a California town in denim cut-offs, Dern’s character plays at being a grown-up until she starts attracting the kind of adult attention she’s not equipped to handle. In the film, she’s preyed on by a deeply creepy older man; in reality, as a teenager making her way in 1980s Hollywood, Dern recognises now how unregulated it was. “I was lucky to be mostly very protected,” she says. “Because it was crazy then. At 13 I would audition alone in hotel rooms with directors – who were lovely – but that was the way you did it. You went into the lobby at the Chateau [Marmont] and someone said, ‘You can go up to the room now,’ and the director’s waiting and you sit on a bed and read through the scene together. Luckily that wouldn’t happen now, for either the filmmaker or the young actress.”

“I was kind of a weirdo. My friends had posters of the cute boy from the band, my wall had Barbara Stanwyck, Katharine Hepburn, Édith Piaf and Lucille Ball. Those were my first female icons. And they all make sense in terms of what I’ve gotten to do, but also what I’ve longed to do and what’s inspired me” – Laura Dern

If there was a fork in the road of her career, this was it: she had auditioned for a couple of John Hughes films – Sixteen Candles, The Breakfast Club – and then found herself in Bob’s Big Boy diner having malts and french fries with David Lynch. She didn’t get the Brat Pack roles – maybe her features played more grown-up than Molly Ringwald-cute, a bonus in avoiding teen-star traps. But she did land a movie of severed ears and sadomasochism called Blue Velvet and, in the process, discovered the director who proved to be “the miracle” of her career. She was 17 and had emancipated herself from her parents – a move that sounds acrimonious but she has insisted was purely a legal formality, to allow her to act on adult film sets without their approval. She had moved out of home – incidentally her roommate then was spiritual guru and current long-shot Democrat nominee Marianne Williamson – and was ostensibly heading to UCLA to study psychology and journalism. Days into the course she left to shoot Blue Velvet and joined the college of Lynch instead, an instruction and a friendship that has extended from that meeting in Bob’s Big Boy to the week before we meet, when she, her ex-boyfriend Kyle MacLachlan and Isabella Rossellini jointly presented the director with an Honorary Oscar for lifetime achievement at the Governors Awards. (These days, she and Lynch meet regularly for fried chicken at the Chateau Marmont. His nickname for her is “Tidbit”.)

A director more likely to expand on the joy of a fine coffee bean than unpick the details of his script, Lynch has never really auditioned his actors – so what was it he saw in Dern that day over fries? “I know he was looking for someone he believed was really pure,” says Dern. “Not in a physical way, like, ‘She looks like a girl next door,’ but pure of heart, maybe. Not jaded, not cynical. And that is the one thing I will say for myself. I’ve been very lucky in many ways, but I’ve been through my own version of a lot, my own heartbreaks, we all have, and I’ve not become bitter ever, over anything. It’s part of my constitution and I think David really likes that. I can be dramatic or emotional or scared, but he needed Sandy, at her root, to be such a believer, so hopeful, such an optimist, and that really is my nature. Because, yeah, he hadn’t auditioned me. He’s never auditioned me. Shit, if he does now, I may never work with him again. Luckily I just keep fooling him.”

As a teenager fully immersed in the golden age of 1970s filmmaking, Dern was right at home. Lynch has given her a kaleidoscope of roles most actors only dream of: Sandy’s bottled innocence in Blue Velvet, followed by the raunchy, bubblegum-chewing siren Lula in Wild at Heart. That film marked the first of frequent collaborations between Dern and her mother on-screen – Ladd plays Lula’s martini-soused witch of a mother, with copious hairspray and lethal peach fingernails – at one point she actually rides a broom. (Dern has joked it was like free therapy.)

Her intuitive feeling for Lynch’s tone – that uncanny mix of gnawing dread, horror and absurdity – has made her the director’s ideal accomplice, and together they’ve taken vertical plunges into the murky pit of our collective unconscious, most completely in 2006’s Inland Empire, in which Dern digs at some unimaginable sickness crawling underneath Hollywood’s shiny surface as an in-need-of-a-comeback actress who shatters into multiple personas. In inimitable style, Lynch called on the Academy to give Dern an Oscar nomination for that role by sitting at the corner of Hollywood Boulevard and La Brea beside a live cow and a giant poster of Dern emblazoned with the words ‘For Your Consideration’. The bovine-based strategy didn’t succeed, but as a surreal show of support, it’s hard to beat.

“I walked up to Greta afterwards and said, ‘Look, we don’t know each other but I’ve got to tell you I’ve never had this experience of watching somebody on-screen and saying, ‘Oh my God, that person reminds me so much of myself’” – Laura Dern

She did get an Oscar nomination for Martha Coolidge’s Depression-era drama Rambling Rose – her mother was nominated for the same film, marking a first in Hollywood history. Dern still has the revealing fern-green dress she wears in one unforgettable scene, in which her character Rose sashays into town, causing multiple jaws to drop. It’s one of only a few souvenirs she has kept, but each holds a kind of talismanic resonance. She has Nicolas Cage’s infamous snakeskin jacket from Wild at Heart (the pair had a brief relationship back then). She has the white suit she wore as the lesbian character Ellen DeGeneres comes out to in the watershed episode of the latter’s sitcom in 1997 – it was so contentious at the time, there was a bomb threat on-set and roles dried up for Dern for a year after the show aired, not that she had any regrets. And she has her ‘Wonder Girl’ T-shirt from the black comedy Citizen Ruth, Alexander Payne’s 1996 debut feature, in which she plays a pregnant drug addict fought over by pious pro-choice and pro-life supporters, eventually out-scoundrelling both sides. It’s a role she sees as drawing a line in the sand. “It taught me about comedy in the darkest of places. It taught me about not giving a shit about anything that anybody thinks – not how I look, not who I am,” she says. Dern had recently returned from fighting velociraptors in Spielberg’s box-office behemoth Jurassic Park, the highest-grossing film in the world at the time. It’s fair to say she was getting some offers with lucrative price tags. “I had just done Jurassic Park and I was following it by doing a comedy about abortion by a first-time director,” she says. “It was a very radical choice that a lot of people were nervous about, because I was being offered a lot of other opportunities. So it was sacrificial in that way. I think it was really the moment I said, ‘I’m going to be an actor.’”

A few hours after we talk, Dern will exchange the fluffy cloud of a white sweater she’s wearing for a floor-length Chanel gown to drop in to MoMA, where she’ll be feted for exactly those kinds of unconventional choices at a film benefit in her honour. As Scorsese has noted, she is the rare actor who has shaped a career in the way a director might, rather than being buffeted by the fickle winds of lucky breaks and conflicting schedules most actors fall prey to – there aren’t many missteps in her lengthy filmography. (OK, perhaps one misstep, and even that is worthy of a brief tangent. In 1983, Dern flew to Hungary with then-unknown actors Charlie Sheen and George Clooney to shoot a sequel entitled Grizzly II: The Concert. The trio were playing teens attending a rock concert through which a wholly unconvincing animatronic bear rampages. The first and last film by a Hungarian director named André Szöts, production was halted when someone stole the funds – the culprit has never been charged and Grizzly II was lost to the dustbin of history.)

These days, the actress is in the enviable position of having directors write roles with her in mind: her two most recent parts were both hers from the start. In Greta Gerwig’s beguiling adaptation of Louisa May Alcott’s novel Little Women, she’s that big-hearted matriarch Marmee. But where previous versions have painted the character with a syrupy glaze, Gerwig is more interested in the conflicting tugs of a dogged survivor trapped in an era when women’s silence and self-sacrifice were seen as virtues. Marmee was based on Alcott’s own extraordinary mother, Abigail, one of the first paid social workers and a committed abolitionist. Gerwig collapses the space between Alcott’s novel and the author’s reality, creating a meta update that unpicks sexual politics, ambition and art. “We’ve all fallen in love with certain literary characters and that mother is almost an archetype – angelic, always says it right, imparts wisdom. In truth, that’s not who Abigail was,” says Dern. “She shared the mess with those girls, and they had nothing, it was beyond poverty.” Gerwig, who has likened Dern’s unpredictable performances to watching a magic show, had long been plotting a collaboration, and the two now consider themselves family. “I knew Ben Stiller, so I had come to an early screening of Greenberg,” says Dern. “I walked up to Greta afterwards and said, ‘Look, we don’t know each other but I’ve got to tell you I’ve never had this experience of watching somebody on-screen and saying, ‘Oh my God, that person reminds me so much of myself.’’ We talk with our hands, we’re gawky in the same way, we have the same long features and arms and body. Then, when Greta was casting Lady Bird, she said, ‘I found our other sibling in this girl Saoirse Ronan’ – we’re all kind of similar featured. So we said, we’ve got to make movies together for ever.”

In Alcott’s picturesque hometown of Concord, Massachusetts, the cast, including Ronan as rebellious, ink-stained aspiring writer Jo, lived together in a timbered barn, slowly melting into the amorphous family that Gerwig captured on celluloid, tumbling over each other and absolutely at ease. “We’d have dinners together, read excerpts of the book and the script, share stories and read poetry and talk in front of the fire,” says Dern. “Greta wanted it to feel messy and floppy and human and hippie. So my job was to make sure they had their hands on me all the time. My daughter is never not touching me. There’s no boundary with your children, and you never see that on-screen in the way we deserve to.” In real life, Dern shares her mid-century Mandeville Canyon home with 18-year-old son Ellery, 15-year-old daughter Jaya, an adorable black labrador, assorted surfboards and Golden Globe statuettes, and a miniature T-rex figurine – a gift from Spielberg – that guards the front door. Her children’s father is singer-songwriter Ben Harper – he and Dern were married for eight years, before divorcing in 2013.

“It’s kind of amazing that tides are changing and there are enough characters to play this whole other world – of what it means to be a woman... Really, we’re going to see storytelling as we’re living it” – Laura Dern

Divorce – not hers, but director Noah Baumbach’s split from actress Jennifer Jason Leigh – was the kernel of this year’s Oscar magnet, the eviscerating break-up saga Marriage Story. Dern wields every inch of her considerable height as the devilishly manipulative Hollywood divorce lawyer Nora Fanshaw, queen of LA’s legal piranha pool. At the pinnacle of her game, all pointy elbows, red stilettos and impossibly taut outfits, she ushers her client through a thundercloud of crisis with utter ruthlessness. “I think she’s the first character I’ve played who doesn’t come from deep insecurity,” Dern says with relish. “She’s in it to win, no matter the cost. She’s absolutely in control and will never lose her cool. I mean, my God, what a boss.” The masterful monologue the actress unleashes midway through attacking the double standards imposed on mothers was, she says, “the greatest Christmas present I ever received”, and she delivers it exquisitely. Journalists have noted that Big Little Lies’ Klein and Fanshaw share similarities – well, one: they are both extremely powerful women. And while it’s hard to imagine anyone pointing out that a male actor has played two powerful men in the space of a few years, Klein and Fanshaw do seem to be harbingers of a more expansive range of roles being written for, and often by, women. “I’ve spent 20 years playing the broken, wounded girl who would never get a shot in the room,” she says. “And it’s kind of amazing that tides are changing and there are enough characters to play this whole other world – of what it means to be a woman and enter this or that workplace, and how they’re treated. Really, we’re going to see storytelling as we’re living it, because we’re all just getting used to it.”

In December, Dern won the New York Film Critics Circle award for Best Supporting Actress for her roles in Little Women and Marriage Story, a prestigious double honour. Later that month, she received two further nominations in that same category, this time for Marriage Story and Big Little Lies at the Critics’ Choice Awards. A further two nominations came in January this year – Academy and BAFTA awards – for Marriage Story alone, which also won her a SAG Award.

Back in 2011, Dern’s furious, mascara-stained face rose up on a giant billboard on Sunset like some Cassandra looking into a future we hadn’t quite evolved towards yet. The image announced her short-lived HBO series Enlightened, which Dern co-created and in which she played the at-times excruciating whistleblower Amy Jellicoe. (“I’m tired of watching the world fall apart because of guys like you,” she says in the finale, before her boss calls her a “psychotic fucking cunt”.) Now considered an early forerunner for the likes of Fleabag and retrospectively mourned for its cancellation, Enlightened clearly arrived a few beats ahead of its time. Which is why the so-called Dernaissance has it backwards. Dern has been a courageous presence on our screens for as long as many of us can remember. She hasn’t changed, but the climate is reshaping around her. Today, in her early fifties, she can wield a laser gun in The Last Jedi, step into the heels of Agent Cooper’s mysterious assistant Diane in the latest series of Twin Peaks, and revisit her role as feminist paleobotanist Ellie Sattler in Jurassic World 3, when actresses of her age in previous decades were quietly being relegated to an ever-diminishing circle of stereotypes. With her Little Women and Big Little Lies co-stars (the latter share a WhatsApp group, go bowling together, see each other’s films, have long, wine-fuelled dinners), she is building a creative tribe of women around herself not entirely unlike the firecrackers from her childhood. And with her own production company, Jaywalker Pictures, founded in 2017, Dern is now in the business of not just playing but creating the kinds of complicated roles and subversive stories she’s often found Hollywood to lack. One project is a co-production with Amy Adams to adapt Claire Lombardo’s sweeping, multigenerational novel The Most Fun We Ever Had.

If the Dernaissance is rooted in a single notion, then, it is Laura Dern reaping what she has sown. She has always been an actor, not a celebrity. By many accounts she is a team player on set, preferring to be in the trenches with the crew than hiding out in an air-conditioned Winnebago. She has long followed her parents’ advice to choose pithy character parts with directors of vision, whether she’s on screen for ten minutes or two hours. She’s swerved the kind of surgery that has made masks of some of her peers (she makes a point never to filter her selfies, too). Now, as the tectonic plates of the industry she has grown up in begin to creak and shift, Dern has found herself on top. And that is right where she belongs.

Hair: Esther Langham at Art and Commerce using Foil Frizz and Static Control Spray by R+Co. Make-Up: Francelle Daly at Art and Commerce using Lovecraft Beauty. Set Design: Piers Hanmer. Manicure: Megumi Yamamoto at Susan Price NYC. Digital Tech: Henri Coutant. Lighting: Romain Dubus. Photographic Assistants: Gaspar Dietrich and Stefano Ortega. Styling Assistants: Desirée ADédjé, Jasmine Morales and Helen Franco. Hair Assistant: Gabe Jenkins. Make-Up Assistant: Agus Arcidiacono. Production: One Thirtyeight Productions. Production Assistants: Jacob Gottlieb and Andrew Gowen. Post-Production: Stéphane Virlogeux.

This story originally appeared in AnOther Magazine Spring/Summer 2020, which is on sale internationally from February 13, 2020.