Walking around Kyoto and Tokyo last November, I recorded three sightings of kimono worn on the street. One was on a middle-aged woman stocking up on incense at the foot of the Kiyomizu-dera Temple, in Kyoto. In streets lined with tourists clearly wearing cheap rental kimono, her look stood out: certainly not-for-hire, her over-kimono was pale pink with darker pink embroidery and toothpaste-green lining; she wore big splashes of blusher, with her hair in a perfect chignon. The second was on a group of three geisha travelling on a bullet train – one senior geisha, leading two young maiko, or geishas-in-training – recognisable by their full traditional kimono, white-painted skin and delicate floral kanzashi (hair ornaments) woven into their buns. And though you might live in Japan and never see an actual geisha in your lifetime, my third kimono sighting was somehow rarer still: inside a fashion afterparty, at what was described to me as “the most iconic gay bar in Shinjuku”, on a woman dancing and smoking with her eyes shut to A-Ha’s Take On Me.

Afterwards, I thought about how those different situations speak to the charged complexities of a garment which is easily definable in shape – straight-seamed, wide-sleeved – but hard to absolutely pin down in terms of use: the kimono has been both formal and casual, liberating and restrictive, masculine and feminine, for centuries now.

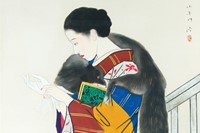

Speaking to these ebbs and flows in use, Kimono: Kyoto to Catwalk – opening this Saturday, February 29 at the V&A – will propose the kimono as a constantly evolving icon of fashion. Going back to the beginning, it will take stock of centuries of the kimono: from the 16th century, when it became the principle garment worn by people of all social standing in Japan; to the Edo period, between the 17th and 19th centuries, where the growth of the rich merchant class allowed different designs, patterns and materials to flourish; to the post-world war two period where the kimono stops being an everyday item of clothing, instead becoming a codified symbol of being Japanese in a newly globalised world; to its current status, whereby a younger generation are beginning to rediscover and twist the ways it can be worn.

What’s more, as the exhibition’s curation (by Anna Jackson) attests, while the kimono is embedded in Japan’s cultural consciousness as a national mode of dress, it has also lived many lives at home and abroad: proving a certain malleability that has spoken to different eras, especially in high fashion. In the 1970s, a certain rockstar fascination with all things unfamiliar led to a certain Japanophilia – Bowie created the costumes of his alter ego Ziggy Stardust in collaboration with Japanese designer Kansai Yamamoto, and Freddie Mercury equally wore vintage women’s kimono as a challenge to binary gender norms. And in the heyday of the rockstar-couturiers like Alexander McQueen and John Galliano in the 90s and 00s, it similarly emerged as a garment that could free them of a Western overreliance on draping a woman’s body to create new forms. Instead, it becomes a kind of canvas: a new set of rules within which to play. Of course, an image like Björk on the cover of Homogenic receives a different response today than it may have done at the time; explicit japonisme is quickly levelled with charges of cultural appropriation instead of appreciation. The exhibition examines that line and where it is drawn, arguing that the kimono has always been a symbol of mutual interaction between Japan and the rest of the world.

But what does the kimono mean for designers born in Japan – many of who, from the 90s onwards, began to study abroad in Paris? It’s actually the show’s major Japanese designers (Issey Miyake, Yohji Yamamoto, Rei Kawakubo) that show a more uneasy, or at least tentative relationship to the kimono: Kawakubo, for instance, is often seen as rejecting it, but in one dress on display in the exhibition from Comme des Garçons Autumn/Winter 1991, a yuzen artist applies gold and black brushwork just as would have been the case in kimono of Edo times.

For certain designers in Tokyo today, an embrace of kimono actually represents a new form of rebellion – a way to turn to craftsmanship and help employ traditional makers in Japan, as part of the fight against low-quality processes and fast fashion. For others, the easy shape speaks to a comfort that might be extremely useful in modern life. Of the following designers who actively work with kimono now, many even originally focused on western clothing, then were drawn again to the kimono they originally rejected. (Think of it as a bit like realising your parents were always right about who the best bands were.) It makes sense: once it has been long enough so it can feel like a choice, humans do tend to move further inwards to examine our own heritage and identity. After all, the original meaning of the kimono is simply translated as “the thing to wear” – no wonder it comes up more often than some Japanese designers would admit.

Takayuki Yajima of Y & Sons, a menswear label focusing on bespoke kimono tailoring

“My philosophy is kimono for modern everyday life. Yamamoto [one of Japan’s largest kimono companies] was established by my great-grandfather, so it’s a big pressure. I was born into a very traditional family, and then I decided to become a firefighter. After that, I could see the kimono from the outside, and update it for modern everyday life. Our customers are men and young people generally. At first, they can feel trepidation: they feel a little self-conscious, like [when they have] a new haircut. But we make [outerwear] kimono you can wear over trousers and a jumper, and haori [kimono jackets] that are functional and easy to wear. You can even wear them over bicycles! [We don’t want] people to get put off by the different layers. I think that young men are becoming more interested because with society becoming so homogenous and flat due to technology, young Japanese are starting to think about what ‘Japan-ness’ is – and its originality. For me, designers in the west being inspired by kimono is a great thing, because culture always changes with each generation, which creates new culture. It is necessary to embed new interpretations from abroad into kimono – without [worrying about] what you should not change and can change.”

Yasuko Furuta of TOGA, a brand established in 1997 and now showing at London Fashion Week

“My grandmother tailored kimono. I saw this when I was little, and I picked up a needle for the first time because my grandmother taught me how to sew a kimono. That is why I have been concerned with the [garment] since. But I have never used the kimono for my designs or really been influenced by them. The purposes of wearing kimono can be very different [at different times] – I think we have the freedom to choose. I wore a kimono ten years ago when I won the ANDAM in France. I had no knowledge of the kimono – I went to the award ceremony wearing it with a bold colour combination in a masculine style, with the obi belt tied as I wanted it to be. But I have also celebrated it in a traditional way; when I took part in the Shichi-Go-San [the Japanese ceremony that celebrates growth at the ages of three, five and seven] in a Japanese Shinto shrine. [Figures like McQueen and Galliano] will have taken many different inspirations as a design source for making their collection, not just one thing. They would have accepted and tried to understand the cultures of different countries, and put them into their own expressions. I am also influenced by different cultures: western culture, Africa, China and other countries around the world.”

Hiroko Takahashi, a designer making unisex, modern kimono with distinctive geometric patterns

“Kimono were always part of my family life growing up. My mother and grandmother could properly wear them without any help. They would wear their kimono on New Years – I liked it because of the make-up and the hairstyles. The one I wore for my coming-of-age day [the annual celebration in Japan that celebrates youths who have turned 20] had been passed down and is still passed down – my cousin wore it recently. But [when they have theirs], I want my kids to wear my kimono designs! I think young women are more interested in kimono now, thanks to [its appearance in] cosplay and manga. It’s had an impact as it’s made it more casual. Also, the makers’ grandparents established the business. Then the second generation became corporate businessmen – they got away from the craftmanship. But now, their grandchildren are continuing the business, in my generation, and have different, new ideas. This has changed the craft industry in Japan. It’s different generations of rejection. My clients are usually people who won’t wear any kimono, and have been looking for something like this for years; or, they have kimono already, and like the fact that mine are different. I only use white, along with two other colours, ever. I’m often asked if being a woman brings a different perspective to making kimono. In traditional crafts, there are not many women. But for me personally it has never mattered. Apart from when most of the crafts people I called to collaborate with were men – some would hang up the phone! Japan is in a way still very behind in terms of its gender equality. Not many women are working independently like me. I’m in a niche on my own.”

Jotaro Saito, a leading kimono designer making kimono in Kyoto, with a flagship store in Tokyo

“At first I designed western-style clothing, but aged 27 I decided to focus on kimono. [People see me as] a pioneering kimono designer because I show at fashion week, but I personally prefer the traditional way of wearing them. [That’s why] I design the tabi socks, the obi sash and the kimono: a total look. But I respect that my clients want to mix them with other items. When we were first showing at Tokyo Fashion Week it was controversial. But I’m passionate about handing over the tradition to the future. Japan is an island, but for us to rediscover those roots is important. I want to hand down this historic and fascinating garment, but also to instate newness.”

Shueh Jen-Fang of Jenny Fax, a cult girlish label, styled by Lotta Volkova at Tokyo Fashion Week

“For me, the kimono [feels] like hidden beauty. [That’s] why I’ve never used elements from it in my collections. I haven’t used it because the kimono itself is already perfectly in balance – it is very difficult to break that balance. When it comes to western designers using the kimono [and whether that’s culturally appropriative], for me it really depends on the designer. I understand designers who use the kimono as a theme, but translate it to fashion. More light feeling, and fun!”

Kimono: Kyoto to Catwalk, supported by MUFG, is at the V&A from February 29 – June 21, 2020.