“Vicious, You hit me with a flower, You do it every hour, Oh, baby you’re so vicious.”

When Lou Reed sings about the cruelty of attraction in the opening lines of Vicious, on his 1972 album Transformer, he captures brilliantly the dark psychic oscillation between obsession and revulsion. Through the use of a repetitive, abrasive guitar sound and his staccato voice, like a razor blade gently slicing through flesh, he tacitly transfers the hippy symbolism of a freshly plucked flower and eroticises it, tortures it. All love, he muses in Vicious, comes with an emotional price tag.

Another New Yorker of that period who sees beauty in the detritus of the downtown scene is Susan Sontag. She describes photographers as “connoisseurs of beauty, wittingly or unwittingly”. In her remarkably sharp introductory essay for Peter Hujar’s Portraits in Life and Death, Sontag calls them “the recording angels of death”, and writes, “The photograph-as-photograph shows death. More than that it shows the sex appeal of death.”

Willy Vanderperre is most known as a fashion photographer, whose cool and calculated eye has produced some of the greatest fashion advertising campaigns and magazine covers of the last decade. He has immortalised the Kardashian family for Calvin Klein and projected an idealised, sacrosanct beauty for Prada. His dark-tinged, gothic surrealism first began fetishising youth and unconventional beauty in the early 00s. What started as an underground aesthetic pushed through the advertising campaigns of Raf Simons and the pages of Dazed and AnOther would, by the middle of the last decade, rise into a globally recognised pop culture style. Like Andy Warhol’s imperfect, slightly grubby graphic silk-screens of Marilyn Monroe and Elvis Presley, work that was once seen as critical of a mainstream idealised version of beauty, as shocking, the “sex appeal of death” that links both Vanderperre and Warhol’s most iconic works soon became subsumed into the mainstream.

hurt, burn, ruin and more is a self-conscious act of returning to the roots of that sex appeal, the origins of Vanderperre’s melancholia-tinged romantic revolution in photography. Not a negation, but an urgent exploration of the forces that inspired it and catalysed it. Sontag saw that “whatever their degree of realism, all photographers embody a ‘romantic relation to reality’”.

The romance in Vanderperre’s hurt, burn, ruin and more is that of imperfection and a personal rejection of the vanity of traditional fashion photography, in the way that 17th-century northern European Vanitas paintings or memento mori traditionally shunned materiality for spiritual enlightenment. In the large-scale representation of a decayed rose in Untitled #15, we are brought so close to the decomposition of the image that it becomes a new landscape of the imagination, an almost interiorised view, like a proto-psychedelic Blakean vision. “Oh Rose thou art sick,” writes poet and painter William Blake in Songs of Innocence and of Experience, as he takes us on an electric ride through sexual pleasure laced with secrets, shame and guilt. ‘Sub rosa’ is the name given to the rose’s symbolic ancient relationship to silence and secrets. Here, Vanderperre’s scale of display unlocks the secret power of macro photography to fetishise our mortality. As much as it renders the seemingly useless and overlooked fascinating, almost fantastical, it also suggests a fresh life beyond death for the fate of this rose; a spiritual rebirth or even the promise of an afterlife.

In this new series of works we are confronted with Vanderperre’s attempt to capture the double standards of idealised beauty, and a deeper exploration of the very corruption of the essence of beauty itself. The corrupting nature of extreme beauty is an idea brilliantly framed by one of Japan’s most famous post-war authors, Yukio Mishima. In his book The Temple of the Golden Pavilion (inspired by a real-life story of a young monk who burns the most beautiful of Zen temples) we are brought into a psychological paradox beyond mere envy or jealousy, of an obsession with beauty that leads to its fateful destruction. Mishima who famously committed harakiri – a Japanese Samurai tradition of ritual suicide – was also a fan of Noh theatre. In an interview about Noh in 1971, he took the idea further, giving agency to the destructive nature of beauty itself, telling the interviewer: “True beauty is something that attacks, overpowers, robs and finally destroys.” Georges Bataille, the Surrealist author of the influential Story of the Eye, who spent a life-time studying transgression and erotics, wrote: “Beauty has a cardinal importance. For ugliness cannot be spoiled, and to despoil is the essence of eroticism, the greater the beauty the more it is befouled.”

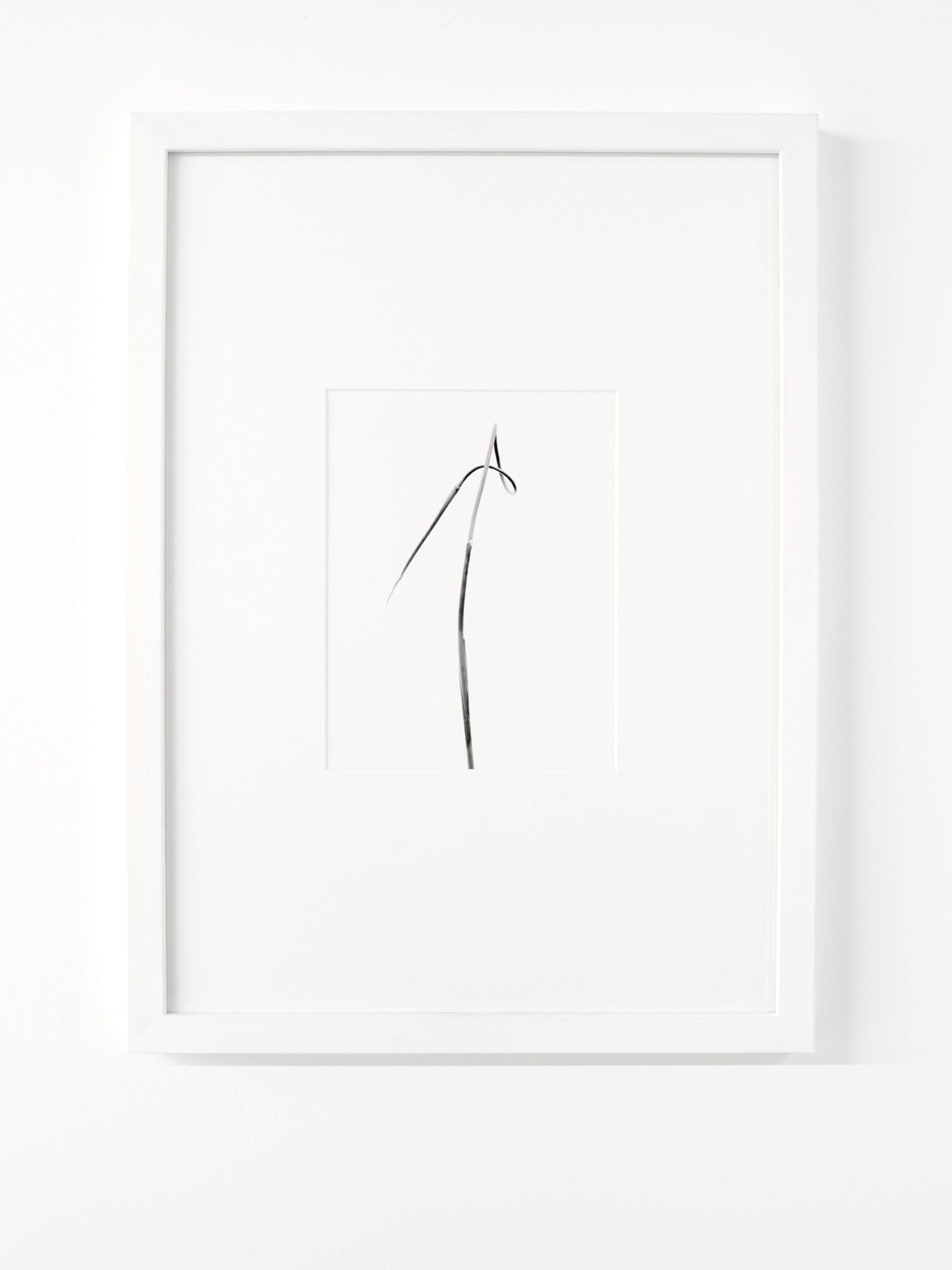

The flower in Untitled #11 curves upwards, a sexualised, single stem of irrefutable beauty. Its silk-thin stamen cradles a smattering of microscopic pollen, its anthers rise in peak production and its leaves dance mercurially, like an ancient deity, ordering the cosmos to bring its energy, via bird or bee or flutter of wind into the magical act of cross-pollination and the spreading of its seed. Flowers in this context can be viewed as our eroticised alter egos, waiting to be hurt, burnt or ruined, or as is the case with this monochromatic white background flash of inspiration, to also be adored, worshipped and deified.

In the creative production of these “flower sculptures”, we see Vanderperre’s relation to beauty and erotics reflected in his own mortality and also his own legacy. The dance of violence and art is a ritual as ancient as the cave paintings of Lascaux. In Untitled #3 we see smashed glass covering a bouquet of thistles, tulips, anthuriums and Birds of Paradise, caught in ballistic flight and fused into the white-heat of a lightning strike. They appear like the photograph of a crime scene shot by Weegee, asking if we should be witness to this death-scene, this torture garden? It feels like the perversion of the ceremonial laying of bouquets on a grave, as if hurled through a night sky in the midst of a storm in a cemetery.

We know from the shotgun paintings of William S. Burroughs and Niki de Saint Phalle that purposefully destroyed art can be more than just an act of pure nihilism. It can be a search for transgression, or even transcendence. We know it from the broken, ruined, imperfection in the Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi, and, more close to Vanderperre’s own biography, we know it from his love of post-punk electronic music – a melancholia wrapped in sharp electronic dissonance, the coded and de-sexualised sound of synths, of the first innocent and exciting sonic merging of human and machines in culture.

The smashed screen of Untitled #1 speaks to the erotised, surreal violence of JG Ballard’s Crash, the automation of life (when the only way to get off is literally to drive high-speed into a wall) and also to the smashed hopes and sexual failures of our mobile screen age. Vanderperre talks about “the aggression of social media” and it must be an almost daily reality for a fashion photographer and their subjects whose imagery is regularly exposed via those automated channels. In Untitled #1 plastic-wrapped bouquets are being suffocated, choked and mangled into fantastic architectural shapes as if caught in a social media car wreck. Is it a reaction to the high-speed collision of images on social media which reduce meaning to surface, and where comments leave no room for morality? On social platforms there are no boundaries, no safe spaces, just a strange generational acceptance of pain and suffering – a barrage of extreme love and abuse in equal measure. It’s something exemplified in the persona of Grimes on her album Miss Anthropocene, a construct for whom extinction is her own rebellion. She describes the album in Interview as “a modern demonology or a modern pantheon, where every song is about a different way to suffer or a different way to die”. She goes onto say, “it’s the sound at the end of the world”.

hurt, burn, ruin and more, represents our collective human fragility, the inevitability of our own plastic-wrapped self-destruction as a species. But it’s not defeatist, there is within it a vital spark, an energy and intensity that wishes to transcend the hyper-normality of conventional aesthetics that hold and frame us in the mirror of our failure. Willy Vanderperre’s work as a photographer has been a study of the energy of beauty, the interior and exterior magic and a search for its soul. When Björk sings “don’t remove my pain, it’s my chance to heal” on notget from her heartbreak album Vulnicura, we tap into the essence of an acceptance of and transcendence beyond failure. To first break denial there needs to be a radical shock to the system, before the broken dreams and smashed hopes are revealed for what they are. In hurt, burn, ruin and more, we see a cosmic explosion of pure life energy and a new potentiality for beauty to emerge from darkness and chaos. Like all natural phenomenon, the new shoots of flowers always lean towards the light.