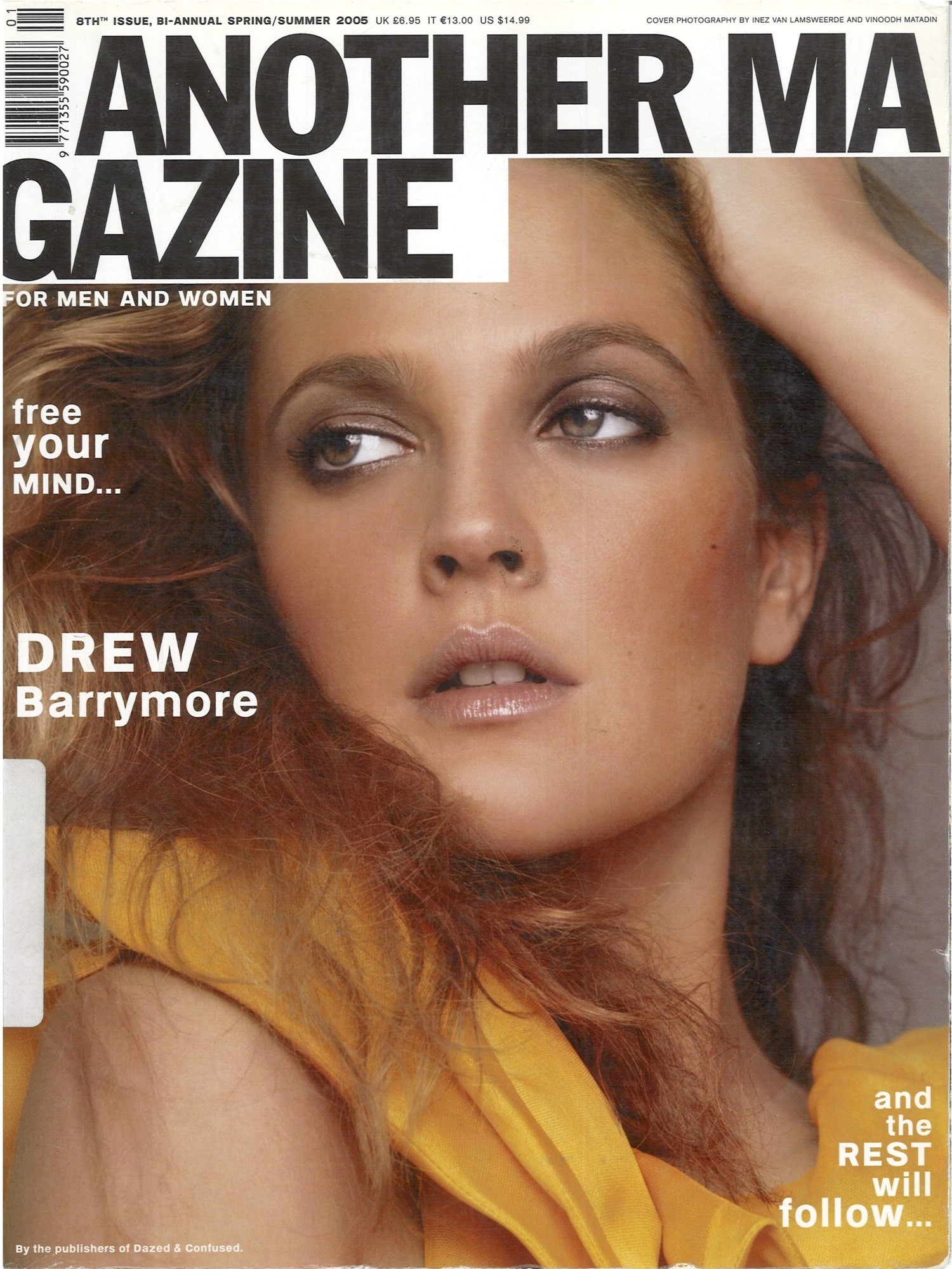

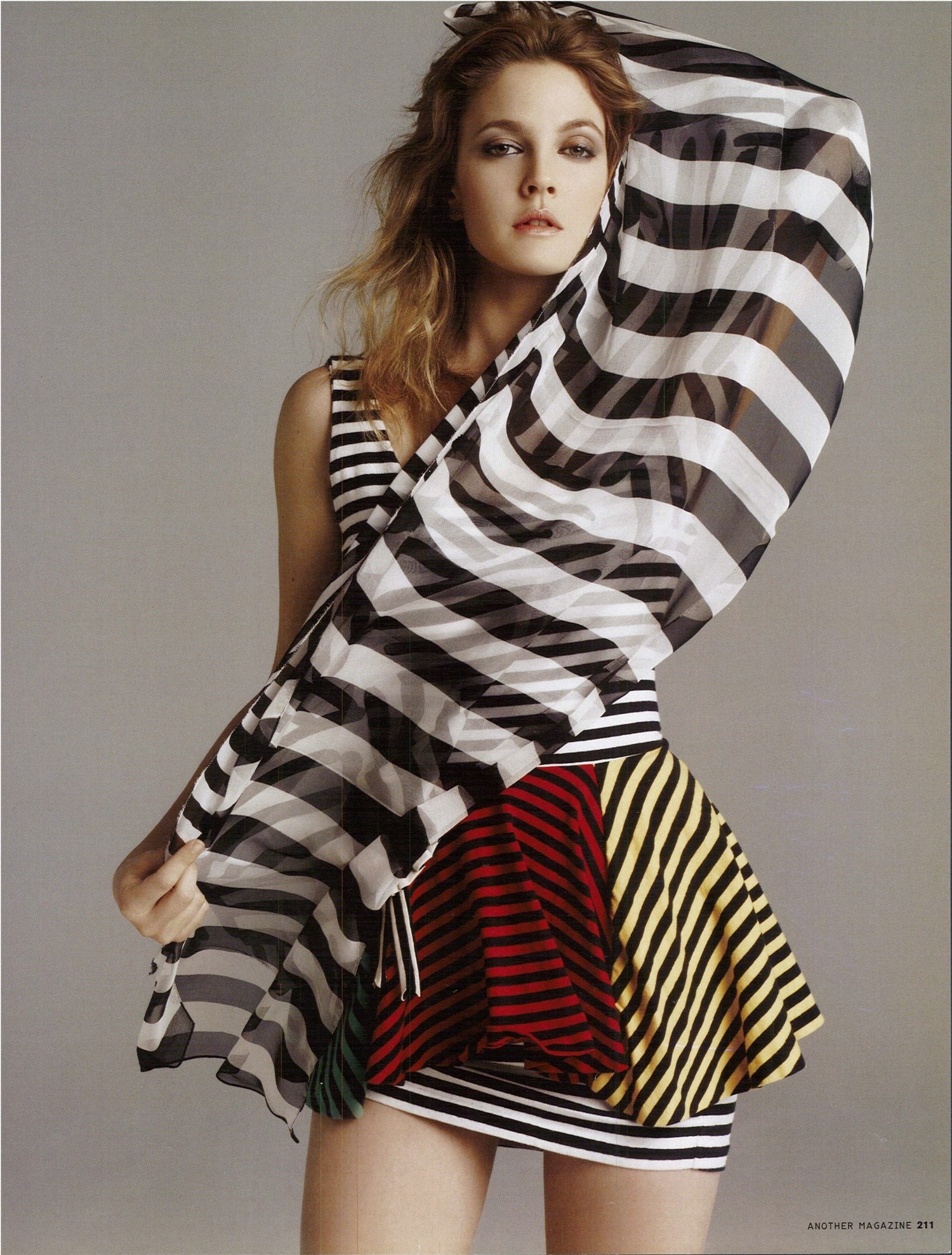

Drew Barrymore turns to face the future as she reaches 30 this month. Drew was the child actor photographed asleep in a smoky fog after-hours at Ma Maison, the eight-year-old with her own entry-card to Studio 54. As the world watched, Drew Barrymore took all the hits, the hardest before she was old enough to drive. But life doesn’t always turn out like the movies. And yesterday’s wild-child on the road to burn-out is today’s Hollywood star of over 50 films.

She is an actor with a string of big-budget roles as the girl-next-door, a producer who took a gamble on a script by an unknown 25-year-old. In that film, Richard Kelly’s Donnie Darko, she played an English teacher with a sharp eye and an even sharper tongue. “Sit next to the boy you think is cutest,” she tells the new girl. Of course. And next Drew Barrymore will be producing the new film by that other American wonder boy David Gordon Green, an adaptation of the Pulitzer Prize winning novel A Confederacy of Dunces. But before that we’ll see her in the film of Nick Hornby’s novel Fever Pitch. Nick Hornby is himself one of two authors commissioned to write short stories starring AnOther Magazine’s cover star. In his story, Hornby casts Drew in a twisted tale of the girl who could have starred in ET. Jonathan Lethem, on the other hand, pits the oh-so-sunny outlook of a girl with a taste for Anaïs Nin and Bukowski, against some foul tempered cultural heroes. These stories sit alongside an interview snatched during an afternoon downtown in New York. With her pompoms out for quantum physics, Drew Barrymore talks politics and democracy, and tells us why it’s mean to pick flowers.

AnOther Magazine: I hear you’re into quantum physics?

Drew Barrymore: In other words, ‘you’re an asshole’. But yes, lately I’ve been introduced to the ‘beautiful world’ of quantum physics. My boyfriend and his father are well versed in it and I’ve always heard them talking about it. I was either always a little bored or uninterested or I just felt kind of stupid. And then I saw this film called What the Bleep Do We Know!?

AM: What was it about this film that inspired you?

DB: You know when you read a line in a book and it perfectly encapsulates how you feel about something and you just get so excited because someone has expressed something that you haven’t been able to put into words? That’s how I felt about this film. The way it explains how the universe works or the science of things or God. Most of all I was amazed that it spoke so much about perception. That everything exists purely in our perception is such a crazy, druggie, interesting, intimidating-yet-setting-you-free kind of thought.

AM: So the point is that what you think is reality is really just your own made up version?

DB: Yes, that you could be creating your own fate. There is something very empowering about the id ea that you are the conductor of your destiny.

AM: Even if it’s all just in your mind?

DB: But it goes beyond that. One man in the film did this experiment where he put words on to containers of water. The water, viewed under the microscope, responded to positive words and formed these crystalline, snowflake formations. And when he put a negative word on the container, under the microscope the water molecules actually looked like they were corroding. We as human beings are 90 per cent water. After seeing this film I felt I had this weird ability to control the chemistry of my emotions. So I’ve got my pompoms out for quantum physics right now.

AM: Give me a Q! But don’t you think that part of your enthusiasm stems from the fact that someone, in this case the director of the film, was able to present this complicated theory to you in a language that you could understand and connect to?

DB: Absolutely.

AM: Was this something you tried to do when you were making your documentary? To talk about politics in a language that a lot of young people would understand?

DB: Yes, quantum physics and politics are definitely two things I really knew nothing about and couldn’t enjoy having a conversation about. I still don’t feel like I’m an aficionado but I’m much more inclined to get involved and learn more and participate, instead of just sitting back and feeling like the dumb one at the table. Because I think that ignorance can make you shy. I understand politics much more now even if it still feels like knives in my organs. I’d never directed before. I didn’t know the documentary world and I didn’t know politics – so these things scared the living shit out of me. Filmmaking and directing were two things I love and have always wanted to do.

AM: I understand you had a very hard time being taken seriously during the entire process. There were nasty stories being published saying ‘Angel Get off the Bus’.

DB: Totally. And that always felt like a good excuse to quit but I knew that I would hate myself if I did. Instead I used the criticism as a strength. But then politics is deliberately set up to make people feel stupid. lt was amazing to discover how much of the set rhetoric you understand when you ask questions. I didn’t realise this until I started editing and molding segments to show how politicians really just appease us, there’s a stock answer for every question. Because politicians are on television, because they’re up on a podium, because they’re in positions of power, our perception of them is that they’re untouchable. And when you’re in a room with them, you realise they are just like everybody else and there’s something sort of sad about that.

AM: As both director and editor of the film you really had the chance to manipulate people’s perceptions.

DB: There is a lot of power in the editing room. You can skew everything to be negative and make anyone seem either really stupid or really smart. I couldn’t believe how scary that power was and I made sure I didn’t abuse it. When you’re editing a film you’re just trying to stick to the story, but with a documentary you are creating your story in the editing room. I entered into it with nothing but the honest notion that I wanted to learn. I hated feeling so stupid and I didn’t really know what I was doing and I was trying to take on all these different tasks having never done them before.

AM: You’ve been producing films for what, ten years now?

DB: I was 19 when I started my company. I didn’t know shit about producing. I really didn’t. And my partner Nan and I were like let’s learn. Let’s not fuckin’ socialise at parties in Hollywood. We just tried to discover what it was we loved about movies and filmmaking. We didn’t want big deals in Hollywood for our company, we wanted to prove that we could do it and earn the right to do it.

AM: And how did you ultimately select the projects that you decided to work on?

We adapted books at first and spec scripts and just tried to find our way until we figured there was really a story we knew exactly how to make, that we wanted to make, that we wanted to spend a year, two years, pounding the pavement for. We finally found it with this script Never Been Kissed. We just really got that story – how you feel so awkward in what you think is a cool world.

AM: I understand you’re reading Dostoyevsky’s The Idiot right now. There is a similar disconnection here between the world you live in and the world in your head. That whole gap in perception thing.

DB: I’m only 100 pages into the book, I’ve got 400 to go! But there is a sweetness about the character in The Idiot, like he’s the sanest person in the room. He’s just being honest and heartfelt and everyone is scrutinising him because they feel like they have to. I don’t see that about myself though. I don’t think I’m smarter just because I’m more heartfelt and I do feel like an idiot a lot of the time. I definitely feel like the court jester to all the royals.

AM: Is that a defence mechanism?

DB: I like looking up rather than looking down. There’s a beautiful theory called animism, which believes everything has a soul. I’m the girl who thinks the elevator is waiting for me. I feel guilty when I eat a carrot or when I pick a flower. I have that weird silly sort of brain that just thinks about all that shit and appreciates the beauty of the supermarket aisle. I love trying to find the beauty, and reason, and give credit to everything around me.

AM: Have you always been this optimistic?

DB: Always. it’s the only way I know how to survive. And it doesn’t mean that I don’t succumb to self-loathing, get morbid, or cynical, or bad-tempered. There are moments but they are fleeting. They are like buttons on a gigantic jacket. The jacket is optimism. Anyone who says they’re happy all the time, it’s just fucking horseshit – but anyone who says they’re dark all the time ... it’s like c’mon, you tell me you never feel joy or the pang of love in your stomach? Don’t pull that dark prince shit with me. We are such multi-layered creatures. We are thinking, feeling creatures and there’s no denying the complexities of it.

AM: But is that a handicap at all in Hollywood? Or is being so nice just your secret weapon?

DB: I don’t know. I don’t know what other people’s perceptions are of me and I don’t like to spend time worrying about them. If you thought that people hated you or didn’t respect you, you would feel terrible inside and so sad. But if you think that they love you, and respect you, I can’t imagine the ego that comes along with that. So I just try to be as good a judge as I can. And I’m not easy on myself. I fuckin’ beat the living shit out of myself. I don’t think anyone could actually criticise me as much as I do myself. It’s never good enough. There’s always something more I could do, something better, smarter, be more hard-working, more disciplined. I do enough of that to myself, but that also doesn’t mean that I don’t care about other people and how much I want to please. I’m a total people pleaser. It’s not so much the approval I seek but the act of doing. I love fucking people pleasing, I live for it.

The Drew Barrymore Stories: Nick Hornby

Nick Hornby is the London based author of four novels, including High Fidelity, the ultimate guide to one man’s obsession with his record collection, and Fever Pitch the story of a life-long passion for Arsenal FC. The former made the successful transition to the big screen in 2000 and now Drew Barrymore is set to star in the screen adaptation of Fever Pitch this year.

Drew had always known this day would come; strange, then, that she should feel so unprepared for it. Maybe it was because she felt so tired when she opened the front door. She’d had a horrible day at work. The kind of day when spooling your life back to the point when it started to go wrong seemed even more therapeutic than a hot bath and an early-evening vodka-tonic.

lt didn’t help either, that her mother was looking after Kimberley that afternoon. She’d always imagined that it would be just the two of them. She’d put the video cassette into the machine, sit Kimberley on her lap and say, “OK. Now, this movie you’re about to watch ... Mommy could have been in it. Mommy could have played the little girl. But Grandma wouldn’t let me. Isn’t that funny?” She wouldn’t make a big deal of it. She wouldn’t say, “We’d be living in Hollywood now, in a house with a swimming pool, if your Grandma wasn’t such a short-sighted, tight-assed control freak.”

She’d never say that partly because she’d be wishing Kimberley away. If Drew had become a film star, she certainly wouldn’t have been working behind a bar the night she met Kimberley’s father – wouldn’t have been drunk enough to sleep with him, wouldn’t even have looked twice. Drew Barrymore the film star would not have been interested in a TV repairman with an ex-wife, two kids and a coke habit to support. If she had become a film star, in fact, she probably would have had her people take Kimberley’s father out of the bar and into the street, where they would have stomped all over him just for looking at her.

They were at the part where Gertie meets ET for the first time. Drew didn’t need or want to watch this again, so she watched Kimberley’s face instead: it was lit up, partly from the TV screen, and partly from within. She looked so beautiful when she was absorbed like this.

“Hi, Mommy,” she said eventually, without turning to look at her. “We’re watching ET.”

“I can see. Mom, can I talk to you for a minute?” She walked over to the kitchen and leaned against the sink while her mother gently eased Kimberley off her lap.

“You’re not going to get mad about her watching this, are you?” Drew’s mother said wearily.

“What do you think?” “I think you are. And I think that would be really unfair. l t wasn’t my idea. lt just happened to be showing on cable. What am I supposed to tell her? That ET’s unsuitable for children?”

“Isn’t that why I wasn’t allowed to be in it?” “lt wasn’t the movie that was unsuitable. lt was the choice of career. I was trying to protect you, Drew. As you well know. Damn.”

“Yeah, well. You did a real good job of that.” “I wanted you to make your own mistakes. Not ours.” Her own mistakes ... She’d certainly got her wish there. Drew had made millions of them. Why would a parent want that for her child? She didn’t want Kimberley to make mistakes, her own or anybody else’s, ever.

They all watched the screen as Cara Clarke, the little girl who’d ended up playing Gertie, did her goo-goo eyes thing at the extra-terrestrial. She could have done something with that part. Drew could have done something with that life, the life that Cara Clarke had stolen from her. The life she’d ended up with ... No one could do much with that.

She poured herself a vodka-tonic, went to the bathroom, ran a bath and lay there until she could hear the closing credits through the door.

The Drew Barrymore Stories: Jonathan Lethem

Jonathan Lethem is an author who draws from a deep well of pop culture influences. Brooklyn based, Lethem has published five novels including Motherless Brooklyn, which featured a private detective with Tourette Syndrome, and The Fortress of Solitude, a tale of two comic obsessives in 1970s New York. His stories have appeared in McSweeneys, The New Yorker and Rolling Stone magazine.

I was riding in an elevator in a London hotel with Alfred Hitchcock and Drew Barrymore. Alfred Hitchcock said, “Do you think he’s opened the box of poisoned chocolates yet?” Though I knew it was only one of Alfred Hitchcock’s deadpan jokes, I grew nervous. Drew Barrymore smiled and laughed, so infectiously that I couldn’t help laughing myself. She said: “I took the poisoned chocolates out and replaced them with chocolates filled with sympathy and affection.” Even Alfred Hitchcock began laughing now.

John Coltrane and Miles Davis and Drew Barrymore and I were backstage at a nightclub in Chicago. Miles Davis was berating John Coltrane for playing a 20-minute solo. I was trying not be noticed. Drew Barrymore was picking through a box of chocolates an admirer had sent backstage, biting into several of them to examine the filling. John Coltrane said: “I don’t know how to stop playing.” Miles Davis said: “Just take the damn horn out of your mouth.” Drew Barrymore said: “Or if you wanted to you could just begin playing very softly, until you were so quiet that the others could play over you.” Miles Davis said: “That would be fine too, yes.”

Ernest Hemingway and Howard Hawks and John Coltrane and Drew Barrymore and I were in a fishing boat on the Snake River in Colorado. John Coltrane and Drew Barrymore were baiting fish-hooks with whiskey-filled chocolates an admirer had sent to Hemingway. I was trying to make coffee on a Bunsen burner. Howard Hawks said to Ernest Hemingway: “I bet you I can make a good movie out of your worst book.” Ernest Hemingway said: “What book is that?” Howard Hawks said: “That piece of shit known as To Have and Have Not.” Drew Barrymore said: “Look over there!” We all turned, and Drew Barrymore pushed Howard Hawks out of the boat.

Gertrude Stein and Jack London and F Scott Fitzgerald and Jack Kerouac and Truman Capote and Drew Barrymore and I were in a large outdoor hot tub in Sausalito, playing a drinking game called “What’s Your Secret?” Gertrude Stein said: “Small audiences.” Truman Capote said: “it’s not your turn, Gertrude, it’s Scott’s.” F Scott Fitzgerald said: “There are no second acts in American lives.” I started to ask him whether he meant that American lives skipped straight to the third act, but the others ignored me. Jack London said: “If you put some eggshells in with the coffee grounds it leaches the acid out of the coffee and it tastes a lot better.” Jack Kerouac mumbled something nobody could make out, and Truman Capote said: “That’s not writing, Kerouac, that’s typing.” Drew Barrymore got out of the hot tub and put on her robe and said: Does anyone want hot chocolate instead of coffee? I don’t have any eggshells, but I do have marshmallows.”

I was running in the New York Marathon with Laurence Olivier and Dustin Hoffman and John Coltrane and Drew Barrymore, only Laurence Olivier was riding a banana-yellow moped. Drew Barrymore was accepting orange slices and dixie cups of chocolate milk from the crowds at the police barriers and laughing infectiously, but Dustin Hoffman and John Coltrane and I were too out of breath to join in. By the time we crossed the Kosciusko Bridge into Long Island City, Dustin Hoffman looked terrible and I was concerned he wouldn’t be able to finish the race ...

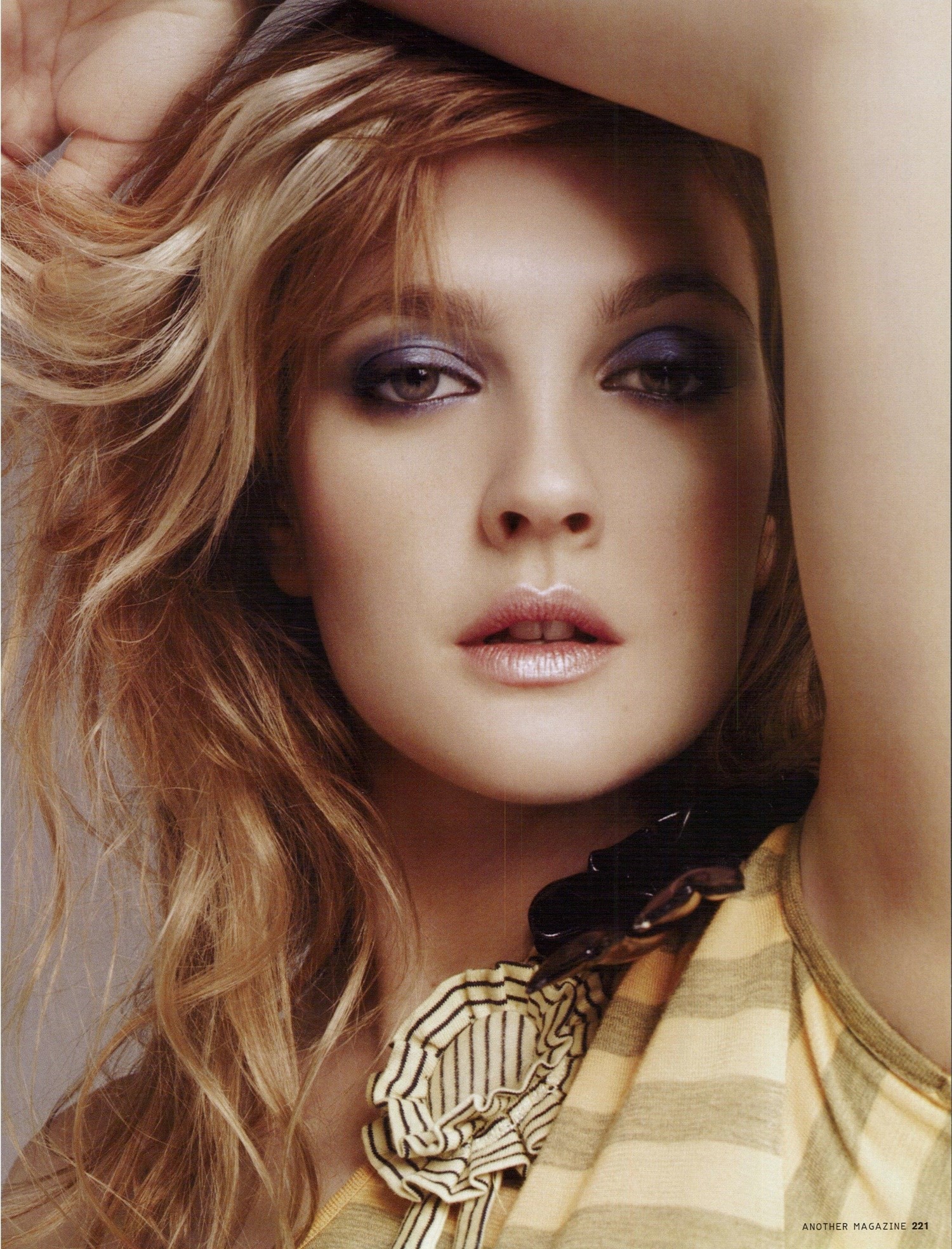

Make-Up: Gucci Westman at Art + Commerce using Lancôme. Manicurist: Deborah Lippmann for LippmanCollection.com. Photographic Assistant: Shoji Kuzumi. Styling Assistants: Stevie Westgarth and Alex Hawgood. Lighting Technician: Jodokus Driessen. Digital Technician: Monique Relova. Printing: Pascal Dangin for Box Studios Ltd. Shot at: Pier 59 Studios New York.

Special thanks to Anne Nelson and Jen Remy at IMG New York.

This story originally appeared in the Spring/Summer 2005 issue of AnOther Magazine.