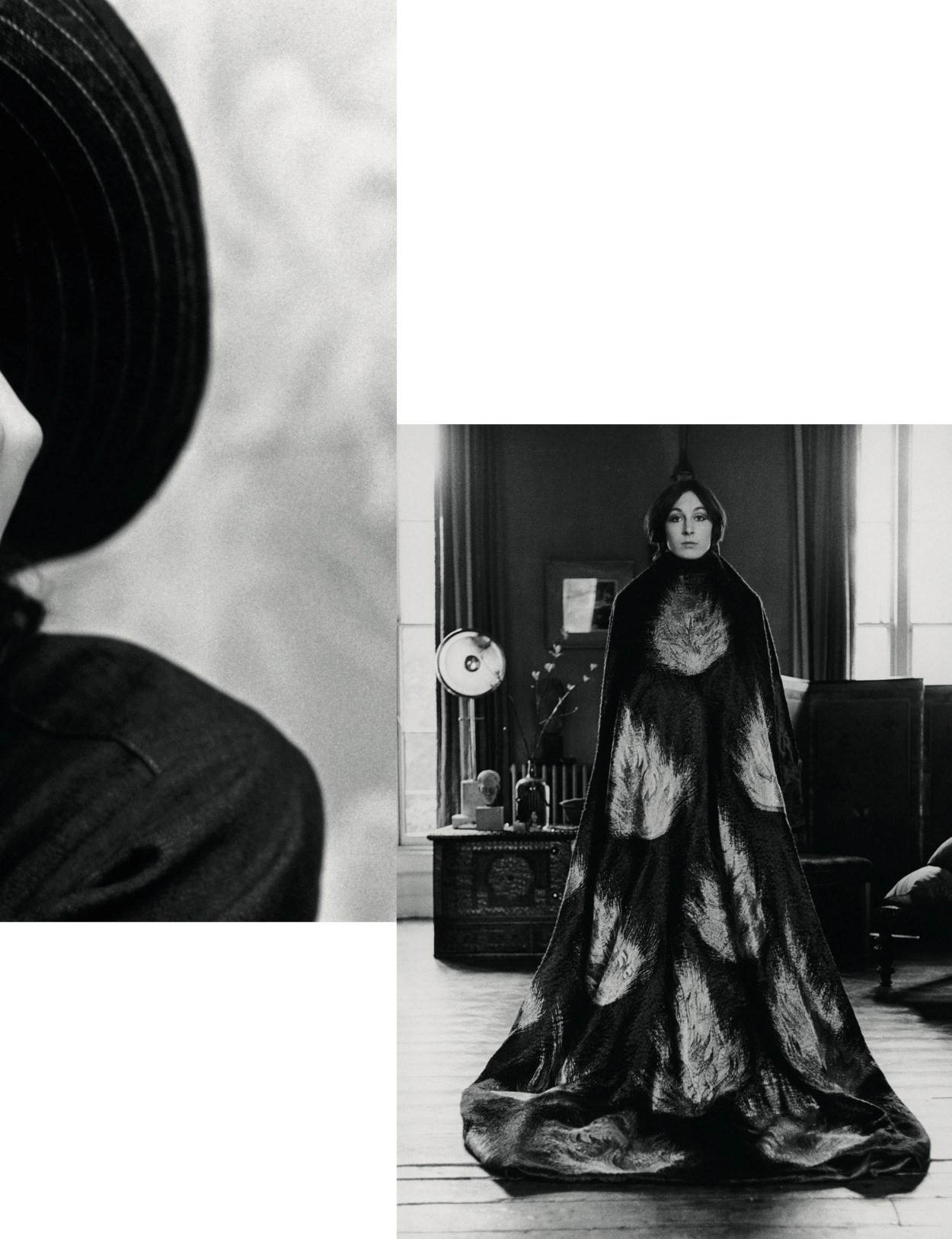

Just up the coast, Malibu has been ablaze for days, but it’s not smoke that is making the air in Santa Monica turbid with haze. A perma-fog has rolled in as a side-effect of a weather phenomenon known as the marine layer. Anjelica Huston couldn’t have asked for a better backdrop. Black of garb and hair, as strong-featured as a warrior queen, she emerges out of the mist like a Gothic vision.

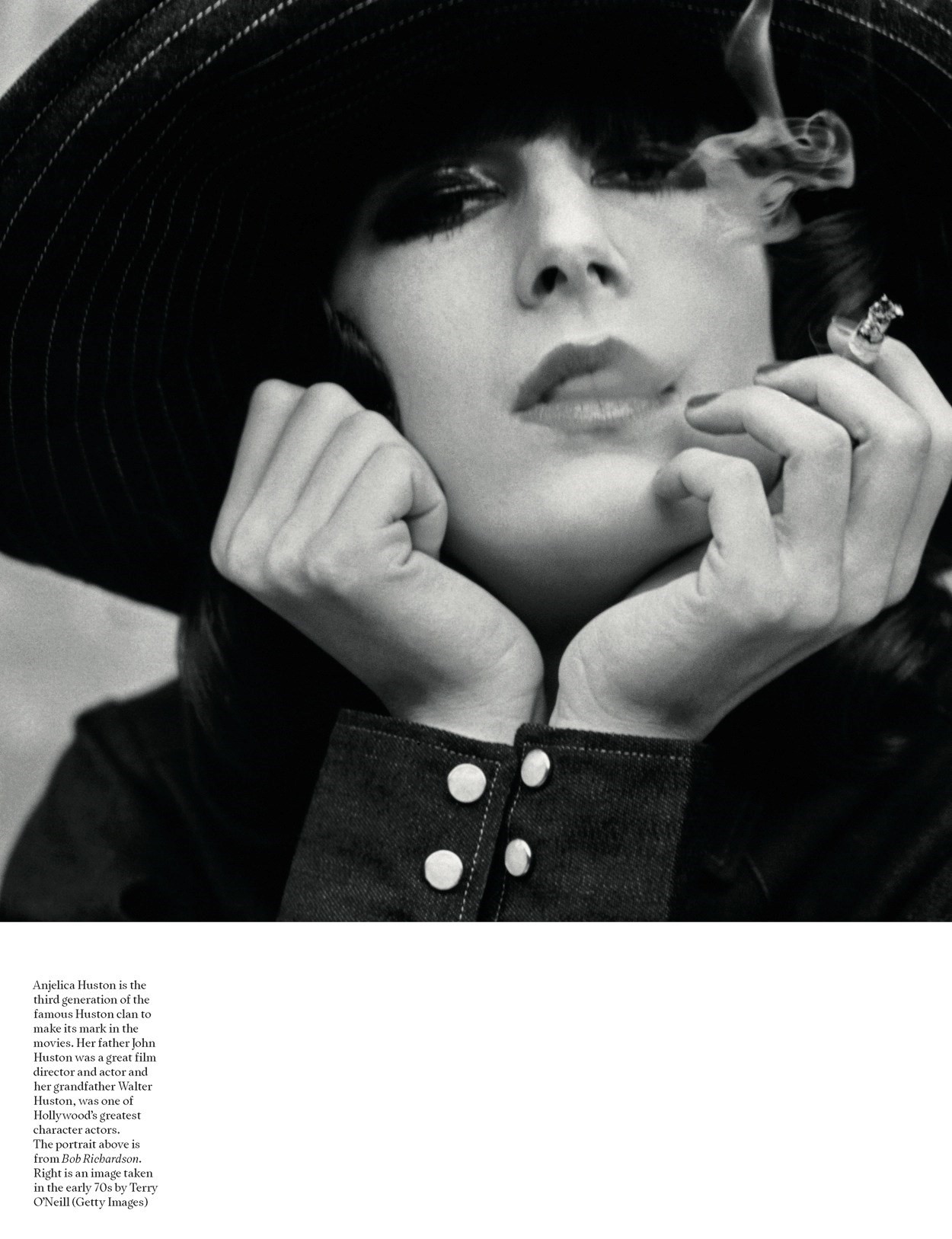

Though I’m exaggerating for effect (she claims she’s prone to the same thing herself), Huston nevertheless has the mien of a genuine icon. Such a label is scarcely more than destiny made manifest for her. Her genes, her life and her work as a model, actress and director have conspired to create a bewitching persona, dipped in darkness. “No, not darkness... mystery,” insists David Bailey, who fell under her spell in the early 70s when Huston was modelling, and is currently preparing a book of his photos of her. They include, appropriately, some of the most memorable fashion images of the era.

She defined that time, as she would go on to define others, but Huston calls herself a child of the 60s. “I still hang my beads, burn my incense, I’m retarded that way. I put scarves on the lamps in every hotel room I go into. I clutter my life with things. I have memories all over that I don’t even necessarily want to remember.” She and her husband, sculptor Robert Graham, famously live in a fortress-like structure in Venice Beach. They’ve just put up a building next to the house for his studio and her offices. “When he walks into my space, his face just registers horror and confusion at the amount of crap, things that assistants framed 20 years ago, stuff I don’t even like, I put it all back up on the wall relentlessly.” While she was moving, she found a box of possessions she’d somehow inherited from a dear friend. “It was his entire life in something maybe the size of a milk crate,” she says. “Anyone who’s expecting that from me has a different story coming. I’ve got house loads.” Inevitable, with all the lives she’s lived.

Her father was the director John Huston, her mother was the prima ballerina Enrica Soma, both products of notoriously demanding professions who wouldn’t tolerate cowardice, reticence or whining in Anjelica or her brother Tony. “I did a lot of things that, on reconsideration, I don’t know that I would have done, to please my father and make my mother happy,” she says. “Hunting sidesaddle, that’s something I’d never do again. It was so dangerous. But he kind of liked that.”

“I clutter my life with things. I have memories all over that I don’t even necessarily want to remember” – Anjelica Huston

Huston remembers her father being away so much he was “a visitor in his own house. When we were little, we were his little adoring ones but then the time came when he returned and found slightly bumptious teenagers who weren’t the enthusiastic jolly children he’d left behind. Then he’d be very critical and I never took criticism well. He came down very hard on both my brother and me when my mother and he split up. He was drinking a lot at the time so he had a very hard edge.”

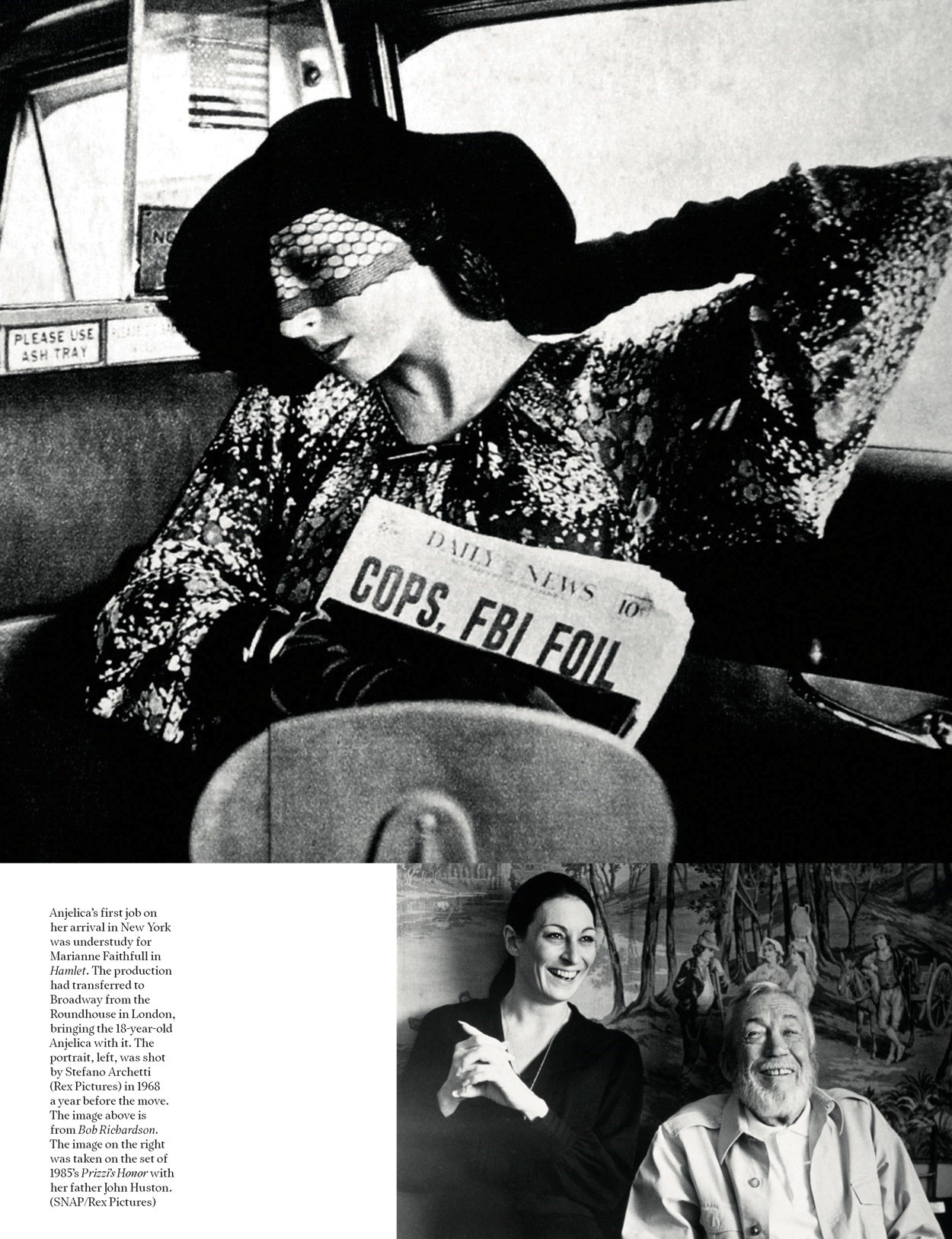

When she was 12 or 13, there was a terrible fight over Anjelica’s unwillingness to go to art school in Paris, her father slapped her, and “that was the end of a decent relationship for a long time. I didn’t want to be around him at that point.” After her parents split, Huston remained in London with her mother. The schism with her father was amplified when Enrica died in a car crash in 1969. She fled to New York. “And before I knew it, I’d taken up with a 42-year-old man, who was not only a good deal older than I was, but also had tremendous mental problems, beyond anything I’d had any experience of.”

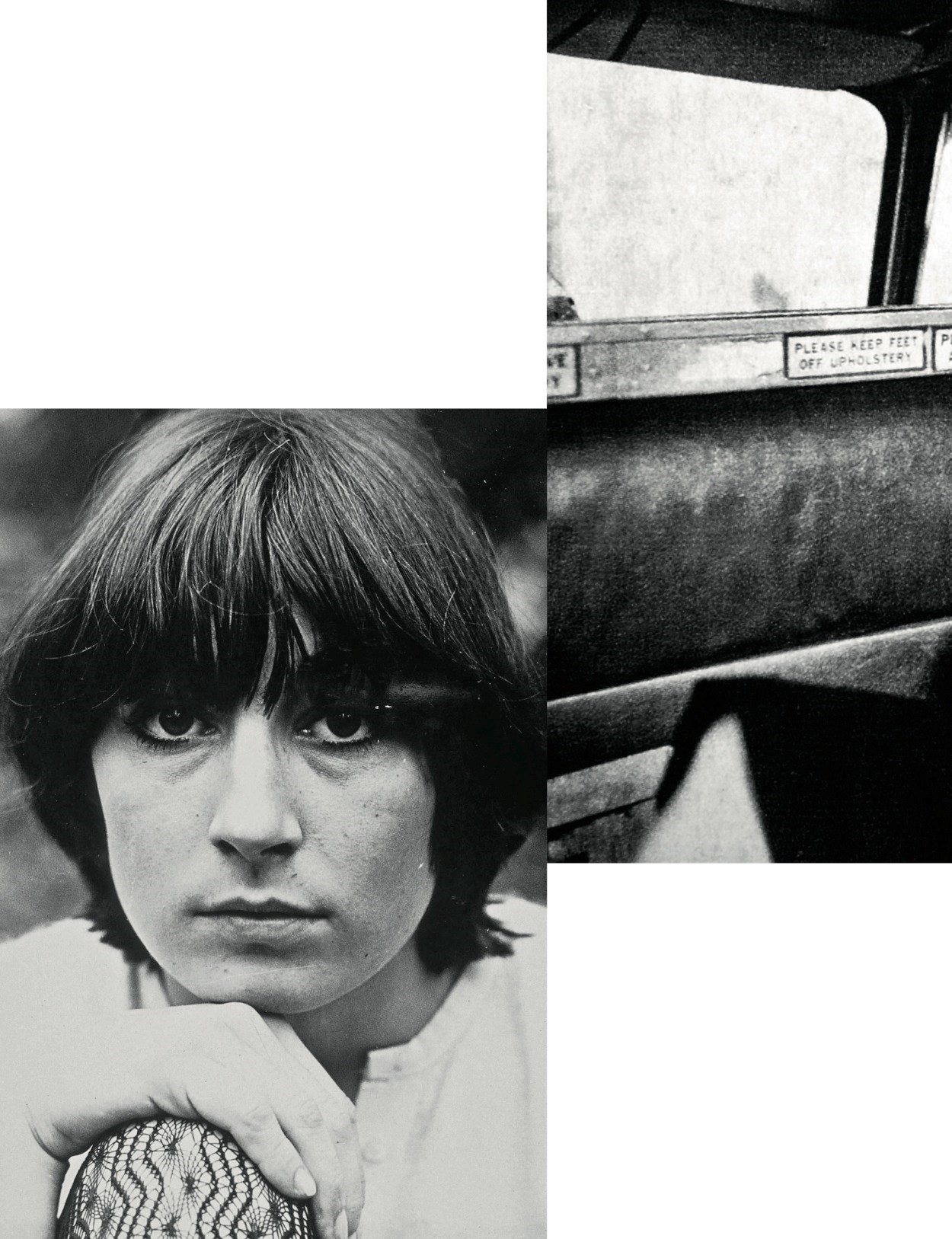

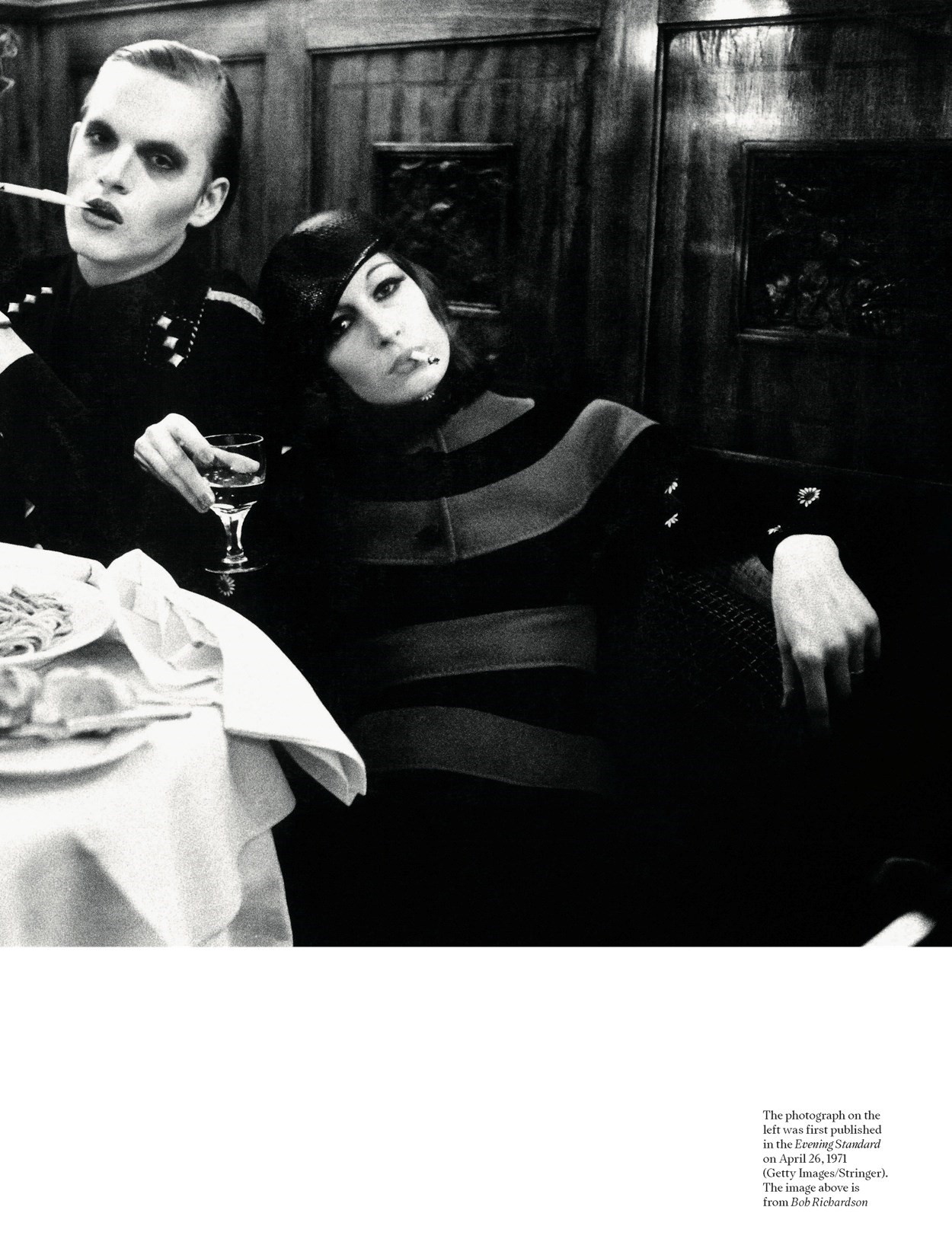

The man was photographer Bob Richardson and, instead of the safe harbour she was seeking, Huston found herself, at 18, the carer. “I didn’t know the ashtrays were talking to him at the time, but he was tremendously schizophrenic and there would be days when he would wake up and the world was worthless and everything in it, and I would think it was my fault, the way that one does when one is being blamed for everything.”

Richardson had been back from Paris for a year, he’d opened a studio in New York and he was in the process of leaving his wife when he met Huston. (She doesn’t believe she caused the split. At least, Bob never said anything like that to her.) He’d also come under the care of a doctor named Max Jacobson, the Dr Feelgood whose shots of methamphetamine and vitamins kept Manhattan’s beau monde humming. “I remember the first time we met, it was my first sitting with Bob, for Harper’s Bazaar. He picked me up in one of those little Mini cars with his big poodle in the back and we raced off to Jones Beach where he sort of hypnotised me. He had me crying and reaching for the sun. It was very powerful. I followed his directions very precisely, he was intrigued because I was malleable, and he liked working with me.”

Getting his models to cry was something of a Richardson signature. That was one way he dragged those cool, perfect beauties off their pedestals and made them fragile, emotional flesh and blood. “He created stories around these women and of course the stories were always him,” says Huston. “The photographs were always about him.” Anyone curious about those stories needs to look at the recent definitive monograph of Richardson’s collected work, overseen by his son Terry. There is Donna Mitchell, weeping on the rocks in Greece (the image that sparked a revolution in fashion photography). And, of course, there’s a lot of Huston, belying her years, breathtakingly beautiful but also haunted and stretched to the limit. She still finds them painful to look at.

Ah, but what a photographer! And, in Huston, Richardson found an ideal vehicle. “The pictures that I thought were particularly brilliant were the ones where he was sent off on his own without an art director or editor looking over his shoulder, and he had that freedom. Often they were really radical, the more radical the better. We did an Irish series for French Vogue in the 70s that had me lying in the road with blood pouring out of my mouth and a rifle in my hand. We did Visconti’s The Damned for Italian Vogue, out there in the train station in Rome with all these older Italian women looking like they wanted to stone us and screaming ‘Puta!’ at me. It was very dangerous for the time, but it was fun, like doing little plays.”

“You have to love unequivocally. You have to be direct in your emotions otherwise you can’t expect anyone to deal directly with you” – Anjelica Huston

The relationship lasted four years, and inevitably, against the days that were dark, desperate and helpless, there were plenty of good times too. Huston was reminded of this when she ran into make-up artist Serge Lutens six years ago, just before Richardson died. “I remarked on what a desperately sad time it was, what a sad man Bob was. ‘I never thought it was such a sad time,’ said Lutens. ‘We did beautiful work.’”

And the Richardson experience surely eased Huston’s work with the other great monstres sacrés of the era. Guy Bourdin, for instance, also notorious for making models weep. “A dangerous little cutie,” Huston calls him. “I shot with him only once. He asked the make-up artist to do glamour make-up on the girls, and I saw this pale blue eyeshadow on my eyelids, and I looked at the other girls and they were so much prettier than I was – I looked so awful – I had a complete breakdown. So these two girls walked me round the square and when we got back in, Bourdin asked me what on earth the matter was, and I said, ‘Oh, my nose is enormous and my eyes are like raisins, I’m HIDEOUS,’ and he said, ‘If you have small eyes, they should be smaller, if you have a big nose, it should be bigger.’ He completely defused the time bomb that I was. And that was it. He laughed at me, then we laughed together.”

From an early age, Huston knew she had something, “Not necessarily a talent like a musician or an artist where you actually present something, but a talent for the transmission of expression – and that was really what I found through acting. I always liked the open-endedness of it, the fact you’re creating something that’s so intangible... I don’t even know if you are creating, it’s more like being a transmitter.”

Modelling was always about acting for Huston. She loathed the way she looked, so her air of haughty self-possession was a great performance right there. “If I’d known I looked half as well at the time, I’d have been much happier about myself,” she acknowledges now. “But I liked working for a camera, I liked the atmosphere of creation, being able to interpret what a photographer or a designer had in mind.” And that self-consciousness successfully translated to her film work. Fashion played a big part in her best-known roles, both Oscar-nominated: Mafia princess Maerose Prizzi in Prizzi’s Honor and the monstrous Lilly Dillon in The Grifters (she won for the former). Lilly with her ash-blonde hair and Azzedine Alaïa dress could have stepped straight out of a Helmut Newton photograph. And no one would have had a better idea of that than Anjelica Huston.

She met Newton, the Alpha to Bourdin’s Omega during French Vogue’s golden age, on the same day that she’d been working with Bourdin. “I’d gone home after the shoot and I was sitting in Tony Kent’s apartment at three in the morning having some vegetable stew and I got a phone call from Vogue asking me to come back to the Place du Palais Bourbon to be photographed by Helmut Newton for the opening page. I’d always heard these stories about how cruel he was to girls and how he shouted at them and so forth but he was so sweet. He was doing those pictures with the red Polaroid eyes. We got on really well and I worked with him quite a lot during that period when he was doing things spilling from glasses. You always got crèème de menthe or milk or something all over you.”

Then came Bailey. He remembers her as a giggling girl of nine when they first met at John Huston’s house off Eaton Square. What she remembers is a call her mother got from Vogue, asking if Anjelica, now a much less giggly 15, could be shot by their superstar photographer. “I walked into a dressing room as Celia Hammond was leaving... the most beautiful girl you’d ever seen in your life, with hair the colour of lemons, skin like peaches and cream, huge blue eyes. I was stunned. The editor came in and said, ‘You know how to do your own make-up? You can do your own individual lashes?’ I said, ‘Oh yeah.’ Three hours later, I’m still wrestling with these Twiggy lashes. They kept checking on me, to see if I was all right. I emerged from the dressing room in some gypsy outfit I didn’t have the courage to say I hated. I get on set, I’m me and I don’t know what to do. Bailey said something like, ‘Do something, missy’ (Huston’s cockney accent is passable) and I said, very coldly, ‘Don’t call me missy, I don’t like it.’ It was a horrible little session. I think he got one bad picture.”

“Actually at one point [David Bailey] said, ‘If I were to ask you to marry me, you’d be a fool to say no,’ and I said, ‘Don’t be ridiculous,’ and it never came up again” – Anjelica Huston

But Bailey clearly liked the backchat. Huston feels it’s because he liked anyone who stood up to him. “He used to prod you till you came back. I think he liked girls with a little wit, that was always his thing. He loves to have a giggle, he doesn’t like to be taken so seriously and it took me a while to understand that, because he came with such a big reputation.”

Years later, Bailey was the photographer, Huston was the model (with Grace Coddington as stylist and Manolo Blahnik as the male mannequin) on one of fashion’s great road trips, winding willy-nilly down the Riviera, then across to Corsica in a raging storm with a plane load of nuns. “We got off the plane and the guy from the tourist board was there to pick us up. He opened the boot of his car and it was full of rifles. From that moment on, we were mystified by the place. Our first night, three Black Mariahs came pouring out of town, there were riot police in the main square. It turned out three towns had been left out of the general vote and they’d come down to the main street of Ajacio to shoot it out... and this was commonplace. Manolo and I had adjacent balconies, and every morning we’d shout shrilly to each other ‘Vive la Corse! Vive la Corse!’”

Bailey and Huston were briefly lovers. “Actually at one point he said, ‘If I were to ask you to marry me, you’d be a fool to say no,’ and I said, ‘Don’t be ridiculous,’ and it never came up again. He was one of those people you could go on being a friend with, there was never angst, it was not about being hurt.” It does, however, seem that their closeness was sufficiently enduring to arouse Jack Nicholson’s suspicions. “Jack did call wanting to know if I was in love with her,” Bailey remembers.

Jack and Anjelica. From 1973 onwards, they were America’s favourite showbiz soulmates, the apogee of cool coupledom. But cool was tough. “Jack was a huge movie star and got a lot of attention and sometimes it was really hard to be around it, because it would come uncensored and very directly if I was with him or not. Girls literally threw themselves at him. And he was all boy. He wasn’t going to turn down anything interesting, particularly if I was away. And I was away a lot. I was working a lot, he was working a lot.” Huston never found a way to turn a blind eye. It was small comfort that she was the one her wayward lover came home to, “particularly if he was coming home with the scent of another woman on his hands. Mostly you take those things as they come and there are moments when you’re really close and other times when you find a letter in a drawer and it drives you crazy or someone comes up and slips a number into his pocket. I know one thing for sure, if you go looking for it, you’re going to find it.”

“Relationships are so mutable,” Huston muses. “There are moments when you think it’s more important than anything to stay together, but you drift in different ways. Ultimately, it’s terribly hard for me to break up with people, but Jack and I had essentially broken up a long time before we did break up. We weren’t living together, we were seeing other people, we weren’t discussing it with each other. A lot of the confrontational quality of our relationship – that confrontation that goes with knowing someone belongs to you – did not exist anymore. But the actual act of breaking up with Jack was huge, it was like breaking up with a parent, it was as hard as any death that I’ve survived.”

It was ultimately her decision, though Nicholson fathering a child with another woman in 1989 didn’t leave her much room to move. I have always thought people should suffer more for what they do to other people in the name of love. “I couldn’t agree more, 20 lashes! ” Huston says with a hearty laugh. “For years, I felt Jack would wake up some day and count the measure of his loss when it comes to me, but I don’t think so. He’s as happy as a clam up there in his lair watching basketball on television, or enjoying whatever it is he’s enjoying.”

“I honestly wish I didn’t take things so hard, personally and professionally. If I can’t make something work I get tremendously frustrated and tremendously down on myself, but I only know that way of pushing myself. I don’t know how not to be that other person who doesn’t put themselves out to be hurt” – Anjelica Huston

She once remarked that, in a relationship, you have to give without any expectation of success. Does she feel this is a woman’s lot in love? “No, I think in a way it’s a man’s lot too. I’m not saying you’re going to succeed at it or there’s a sense of justice to any of it. There is really no justice in love or in relationships. You can’t go into something emotional with a bargain in mind. You have to love unequivocally. You have to be direct in your emotions otherwise you can’t expect anyone to deal directly with you.”

Doesn’t that open one up to a world of pain? “I think one’s being constantly hurt. I honestly wish I didn’t take things so hard, personally and professionally. If I can’t make something work I get tremendously frustrated and tremendously down on myself, but I only know that way of pushing myself. I don’t know how not to be that other person who doesn’t put themselves out to be hurt.”

Huston married Robert Graham in 1992. She uses words like “volatile” and “turbulent” to describe their relationship, which begs the obvious question – were you looking for your father in your boyfriends? Huston gives the slightly less obvious answer. “I probably still am. Most of my boyfriends are strong, they stand up for themselves. I don’t feel they would crumble and die if I was to disappear. Even though you want to feel, to a certain extent, that they can’t live without you, the truth is most people can live without you. If you think they’re going to sob on your grave, re-think – they’re wondering how far that petrol’s going to get them to the next party.”

Where she stands vis-à-vis her beautiful, adored mother is more complicated. “I don’t think I’d have got in nearly as much trouble as I did if my mother had lived,” she says. “I think I was lost – adrift, shall we say? – from several years before her death till I hit my mid-30s. If she’d lived, I wouldn’t have made the mistakes I made. I wouldn’t have spent that long with Bob, my mother wouldn’t have let me. And I wouldn’t have needed to, because I wouldn’t have been seeking that particular watershed.”

It was always too hard for her, for one reason or another, to have her own kids, so maybe it shouldn’t be a surprise that her most memorable roles have been refractions of motherhood. But look at the mothers. “I’m afraid that’s what there is in life for women after a certain age,” she offers mildly. Still, the matriarchal figures she has chosen to play have been either wicked (The Grifters, The Witches), weird (Morticia Addams, two thirds of her Wes Anderson moms), absentee (the other third), or, in her latest film, Choke (a Chuck Palahniuk adaptation), a scary monster who kidnaps a child and turns him into a freak.

She likes being Anderson’s totemic mother figure. “But I’m always a lonely part in his movies. It’s really frustrating because I want to be one of the girls or one of the boys. Still, there’s a fantastic line in The Darjeeling Limited when the mother is asked why she didn’t come to the father’s funeral? and she answers, ‘I didn’t want to.’ Her whole character is expressed in that fantastically liberating line. That’s the way I want to feel, that I didn’t do something because I didn’t want to, rather than making up an excuse, like I had a tummy ache. I’m still working on that, I’m still hiding from the teacher.”

“I wouldn’t mind if Bob Dylan thought my work was pretty great. That wouldn’t kill me” – Anjelica Huston

“I don’t think people have ever cast me for anything too traditional or midwestern or housewifey,” Huston says with masterful understatement. “But I find lately – maybe it’s because I’m getting older – they’re asking me to play smart people, which I’m not so crazy about because it means you have to talk fast.” I suggest that smart people don’t talk, they listen. “If only I could convince the scriptwriters of that!” she whoops. “I love no dialogue – or as little as possible. That’s my ideal.”

Lunch is over and the notion is floated that age can be a liberating force for women. “It’s lovely to be able to befriend women and not feel they’re stalking you for your boyfriend,” Huston concedes with a wry smile. On hearing that my London neighbour Chrissie Hynde was jealous when she heard of our meeting, “I love that,” she says delightedly. “Bonnie Raitt came up the other night and said she liked my work and that made my day. If I’d have had my full druthers, I’d have loved to be a singer, to be able to stand up in front of people and really belt a song, like Aretha Franklin or Maria Callas.”

Then, as this child of the 60s – and every decade since – merges with the mist that refuses to lift, she makes a last wish, “I wouldn’t mind if Bob Dylan thought my work was pretty great. That wouldn’t kill me.”

This article originally appeared in the Spring/Summer 2008 issue of AnOther Magazine.