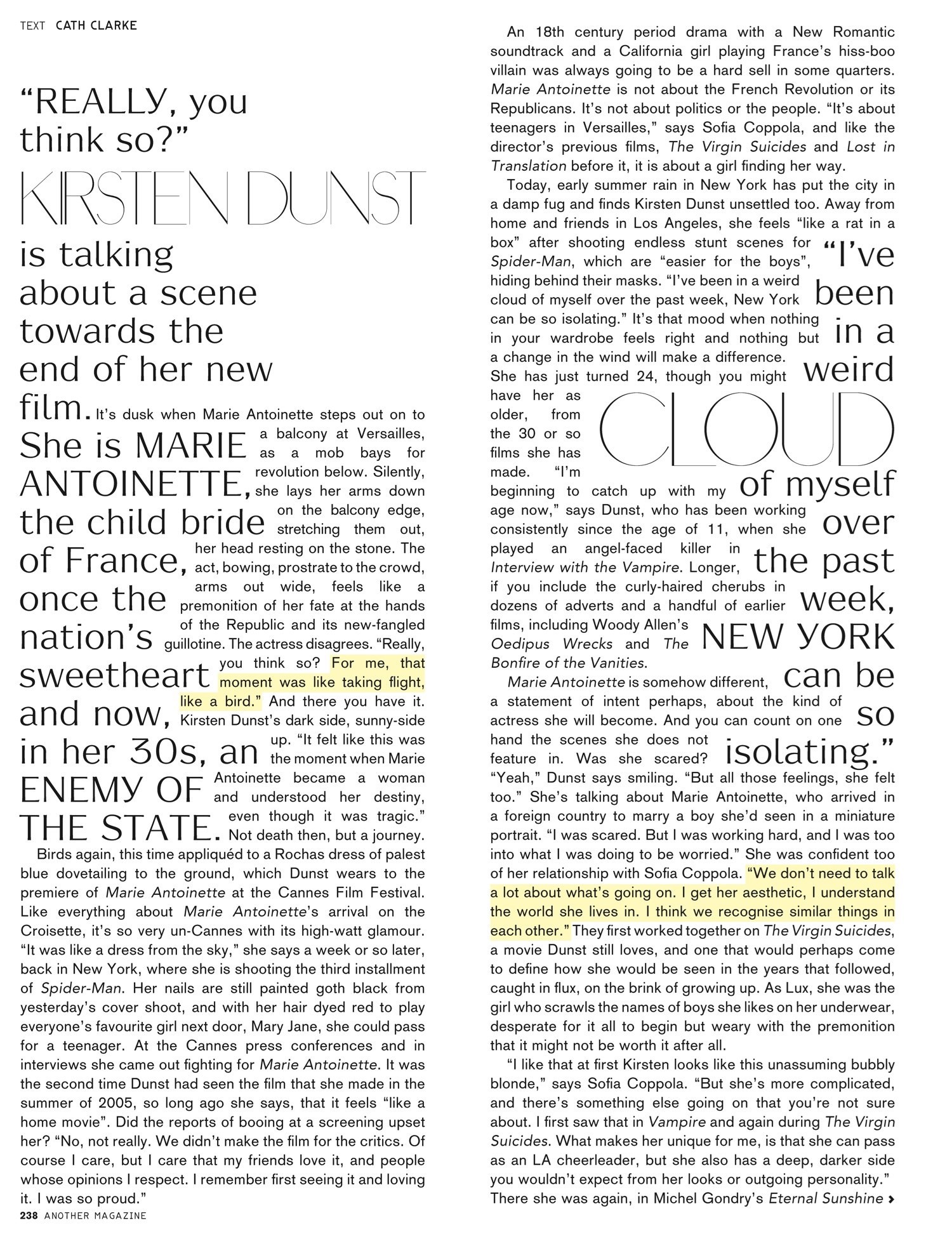

“Really, you think so?”

Kirsten Dunst is talking about a scene towards the end of her new film. She is Marie Antoinette, the child bride of France, once the nation’s sweetheart and now, in her 30s, an enemy of the state.

It’s dusk when Marie Antoinette steps out on to a balcony at Versailles, as a mob bays for revolution below. Silently, she lays her arms down on the balcony edge, stretching them out, her head resting on the stone. The act, bowing, prostrate to the crowd, arms out wide, feels like a premonition of her fate at the hands of the Republic and its new-fangled guillotine. The actress disagrees. “Really, you think so? For me, that moment was like taking flight, like a bird.” And there you have it. Kirsten Dunst’s dark side, sunny-side up. “It felt like this was the moment when Marie Antoinette became a woman and understood her destiny, even though it was tragic.” Not death then, but a journey.

Birds again, this time appliquéd to a Rochas dress of palest blue dovetailing to the ground, which Dunst wears to the premiere of Marie Antoinette at the Cannes Film Festival. Like everything about Marie Antoinette’s arrival on the Croisette, it’s so very un-Cannes with its high-watt glamour. “It was like a dress from the sky,” she says a week or so later, back in New York, where she is shooting the third installment of Spider-Man. Her nails are still painted goth black from yesterday’s cover shoot, and with her hair dyed red to play everyone’s favourite girl next door, Mary Jane, she could pass for a teenager. At the Cannes press conferences and in interviews she came out fighting for Marie Antoinette. It was the second time Dunst had seen the film that she made in the summer of 2005, so long ago she says, that it feels “like a home movie”. Did the reports of booing at a screening upset her? “No, not really. We didn’t make the film for the critics. Of course I care, but I care that my friends love it, and people whose opinions I respect. I remember first seeing it and loving it. I was so proud.”

An 18th century period drama with a New Romantic soundtrack and a California girl playing France’s hiss-boo villain was always going to be a hard sell in some quarters. Marie Antoinette is not about the French Revolution or its Republicans. It’s not about politics or the people. “It’s about teenagers in Versailles,” says Sofia Coppola, and like the director’s previous films, The Virgin Suicides and Lost in Translation before it, it is about a girl finding her way.

“Sometimes I’m waiting for that thing to come over me, where I feel like a woman. Not serious. Not a woman” – Kirsten Dunst

Today, early summer rain in New York has put the city in a damp fug and finds Kirsten Dunst unsettled too. Away from home and friends in Los Angeles, she feels “like a rat in a box” after shooting endless stunt scenes for Spider-Man, which are “easier for the boys”, hiding behind their masks. “I’ve been in a weird cloud of myself over the past week, New York can be so isolating.” It’s that mood when nothing in your wardrobe feels right and nothing but a change in the wind will make a difference. She has just turned 24, though you might have her as older, from the 30 or so films she has made. “I’m beginning to catch up with my age now,” says Dunst, who has been working consistently since the age of 11, when she played an angel-faced killer in Interview with the Vampire. Longer, if you include the curly-haired cherubs in dozens of adverts and a handful of earlier films, including Woody Allen’s Oedipus Wrecks and The Bonfire of the Vanities.

Marie Antoinette is somehow different, a statement of intent perhaps, about the kind of actress she will become. And you can count on one hand the scenes she does not feature in. Was she scared? “Yeah,” Dunst says smiling. “But all those feelings, she felt too.” She’s talking about Marie Antoinette, who arrived in a foreign country to marry a boy she’d seen in a miniature portrait. “I was scared. But I was working hard, and I was too into what I was doing to be worried.” She was confident too of her relationship with Sofia Coppola. “We don’t need to talk a lot about what’s going on. I get her aesthetic, I understand the world she lives in. I think we recognise similar things in each other.” They first worked together on The Virgin Suicides, a movie Dunst still loves, and one that would perhaps come to define how she would be seen in the years that followed, caught in flux, on the brink of growing up. As Lux, she was the girl who scrawls the names of boys she likes on her underwear, desperate for it all to begin but weary with the premonition that it might not be worth it after all.

“We don’t need to talk a lot about what’s going on. I get [Sofia’s] aesthetic, I understand the world she lives in. I think we recognise similar things in each other” – Kirsten Dunst

“I like that at first Kirsten looks like this unassuming bubbly blonde,” says Sofia Coppola. “But she’s more complicated, and there’s something else going on that you’re not sure about. I first saw that in Vampire and again during The Virgin Suicides. What makes her unique for me, is that she can pass as an LA cheerleader, but she also has a deep, darker side you wouldn’t expect from her looks or outgoing personality.” There she was again, in Michel Gondry’s Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, somewhere between girl and woman as she jumped on a bed stoned in her knickers. “I still feel like that,” she says today. “Don’t you hate that? Sometimes I’m waiting for that thing to come over me, where I feel like a woman. Not serious. Not a woman,” her voice deepening for effect. “But I’m constantly back and forth. I like being a girl. I’m bad at hiding my feelings.” It’s true, she doesn’t prepare a face, and often talks in sunny declarations. “Everything is so beautiful there, so decadent. Down to the coffee with a little chocolate on the side,” she says of that very American love affair with Paris she went through while shooting Marie Antoinette. Or, “they were the best fireworks I’ve seen in my entire life,” of the heart-in-mouth display that closed the party at Cannes, where kids down from Paris partied with industry suits listening to Jesus and Mary Chain and New Order. But Dunst’s voice is pitched a little lower than you’d think, and she has confidence in her taste and views, the assurance to call it a spade. Ask her if she related to the young Marie Antoinette, whose marriage at 14 was brokered to secure an alliance between Austria and France, and she’s quick to reply. “I know where you are going with that” – Dunst herself moved from New Jersey to California as a child to make working easier – “but no. You can look for parallels. But I’m not going to hone into how I felt as a child. You know, honestly, I think she is more Sofia than me.”

If there are comparisons to be drawn – and surely there will be – between the world of Marie Antoinette and the here and now, it should hold a mirror up to Hollywood. The 18th-century court is shown as a not so unfamiliar hotbed of gossip, power games and marriages of convenience. Sofia Coppola looks for the intimate moment in history, in which it becomes something far truer. She shows us a snaggletoothed girl of 14 out of her depth walking into a pit of snakes. Teenagers – teenage royalty – flirt and party, staying up till the early hours to watch the sunrise. Coppola finds the pulse of her party people in the self-conscious decadence of the New Romantics. “This heaven gives me migraine,” from Gang of Four’s Natural’s Not In It never rang so true as in the opening of Marie Antoinette, in a heavily scented, sugar-coated world of powdered wigs. An 18th-century Morrissey with a quiff and twigs in his back pocket makes hay at dawn. Bow Wow Wow’s I Want Candy, blares out during scenes of Antoinette’s excesses. Though truth be told, her behaviour wasn’t extreme by the standard of the day’s royalty. She was pilloried by the French gossip sheets for spending the country into ruin, accused of lesbian orgies, countless affairs and was even said to have showed Thomas Jefferson the “royal bush”. We learn from Antonia Fraser’s biography, on which the film is loosely based, that by contrast, Antoinette was sweet natured in that fond-of-animals-and-children kind of way. She cheated on the awkward Louis XVI only after years of putting up with his tweaky hobbies and lack of interest in her. Jason Schwartzman as Louis deadpans: “Did you know the first mechanical locks were made out of wood?” Antoinette’s mother, a fearsome Austrian queen in widow’s weeds, is played by Marianne Faithfull (“The least decadent person in the film, which was a change for me,” she quipped at Cannes).

“I don’t feel that way. I don’t feel successful,” she says slowly. “Nothing changes. I just get more insecure as I get older” – Kirsten Dunst

Marie Antoinette spans more than two decades, from Antoinette’s days as a green Dauphine to matronly queen. It’s no mean feat pulling off the shades of maturing as the years pass, and there are darker moments as the clouds gather over Versailles. Kirsten Dunst’s collaborations with Sofia Coppola have taken her further than in other films. “I think she just lets me be who I am,” Dunst says when asked whether Coppola brings out her dark side. “When you work with certain directors they don’t want all those sides of you. And she wants them from me. I don’t think she brings out my dark side. But she sees it and recognises that and wants that. Not that many people want that from their leading lady. They want you to be their idea of perfection.”

Which brings to mind Cameron Crowe’s Elizabeth Town, in which she played Orlando Bloom’s perky substitute girl, lovely, but maybe just on the wrong side of a man’s cut-out-and-keep fantasy of the girl next door. Her tastes are anything but. At yesterday’s shoot, her soundtrack was The Knife’s Afraid of You. She’s big on Jens Lekman right now, another Swede, who writes black and tender songs about making out with girls in Nietzsche T-shirts. Like Salinger’s Esmé, perhaps, she is drawn to stories of love and squalor – how very Marie Antoinette. And like the thoroughly matter-of-fact young Esmé, Kirsten Dunst too must have been a together child. She was a veteran of 11 when she took the part in Interview with a Vampire. An adult in a child’s body, Claudia was a lover daughter, a troubled character that the novelist Anne Rice wrote after her own daughter died of leukaemia – a disease of the blood. “I think I was old for my age. You can see that with some girls,” says Dunst. Which doesn’t quite go far enough to explain what gives an 11-year-old girl the confidence to go head to head with Tom Cruise. “Maybe it was a need of love and approval by all.” She crumples, giggling. “To be honest, I was a really hard worker, it was a natural thing.” Now it’s a little different. “Now I wonder why I do what I do. I struggle with it. It’s such a funny job sometimes. I like what I do but I hate the things that come with it.” Like inappropriate lines of questioning from journalists. In Cannes, she was asked if she ever had the same problems with men as Marie Antoinette (Louis refused to consummate their marriage for several years). “And this journalist was an older gentleman. I just couldn’t believe he had the balls to ask.”

“Now I wonder why I do what I do. I struggle with it. It’s such a funny job sometimes. I like what I do but I hate the things that come with it” – Kirsten Dunst

All told, it’s a strange industry that puts a 24-year-old at the top of her game. “I don’t feel that way. I don’t feel successful,” she says slowly. “Nothing changes. I just get more insecure as I get older.” More insecure, but increasingly selective too, less willing to compromise. “I’d like to stop for a little while and do a play, take some classes, do something else. It’s scary though, because then you don’t have a schedule for life and you feel a little like a vagabond.” For now, she’ll have to make do with seeing shows, watching bands and hanging out in New York. Her next destination today is a downtown gallery and an exhibition by a Russian artist recommended by a friend. And with that, this cultured vagabond makes her exit.

This article originally featured in the Autumn/Winter 2006 issue of AnOther Magazine.

Photography: Mario Sorrenti, Styling: Tabitha Simmons, Hair: Recine for Infinium by Textureline, Make-up: Linda Cantello at Joe Management for YSL Beaute, Manicurist: Yuna Park at Streeters, Set Design: Philipp Haemmerle, Production: Katie Fash, On site producer: Steve Sutton, Digital Technician: Heather Sommerfield, Photographic Assistants: Lars Beaulieu and Javier Villegas, Styling Assistants: Vanessa Chow and Amy Van Horn, Hair Assistant: Vanessa Mitchell, Make-up Assistant: Renato Almeida, Set Design Assistants: Shaun Kato-Samuel, Matt Jones and Vida Engstrand, Seamstress: Christy Rilling, Motorhome: Citivans, Location Fast Ashley’s Studio, Brooklyn.