John Galliano and Martin Margiela rose to prominence during an era when designer fashion realised its full potential and its main protagonists were afforded free rein to express themselves in a manner that the majority of today’s designers might only dream of. Above all, theirs was a celebration of intense creativity that, in the current climate, seems like the greatest luxury of them all.

The appointment of John Galliano as creative director of Maison Margiela in 2014 seemed an unlikely one on the face of it. The flamboyancy of this, the ultimate designer superstar, a man who took his catwalk bows dressed variously as an astronaut, a matador and a bruised and battered boxer, and whose aesthetic, throughout the first decade of the new millennium especially, was similarly bold, appeared at odds with the house founded by the famously reclusive Margiela. Margiela addressed the press using the pronoun ‘we’ to evoke the spirit of community and, more importantly, to remove himself from the spotlight; the Martin Margiela label was a blank, white rectangle visibly tacked into clothes with a white stitch at each corner, subverting the notion of status and dressing to impress entirely. While Galliano enlisted the services of every big-name model for histrionic spectaculars, Margiela’s shows were worldly, staged in car parks, Metro stations or multiple corners across Paris, the models street cast or friends of the house: more often than not, their faces were masked, suggestive of the anonymity sought by the designer himself.

Any apparent contrasts were also reflected in the designers’ respective exits from the industry. Galliano’s was, of course, in a blaze of publicity – his dismissal, in 2011, from his roles at both his eponymous label and the house of Dior was front-page tabloid news. Margiela, by contrast, quietly bowed out after his label’s 20th-anniversary show in 2008, and while Galliano has returned to fashion, Margiela remains outside it. He has worked on exhibitions charting his work as a designer but is now a practising artist: his first show was a 2019 group exhibition at the Kunsthalle Bielefeld, northwest Germany, fittingly titled L’homme qui marche – The Man Who Walks.

So intent on remaining behind the scenes is Margiela that at least some speculated throughout his career, albeit playfully, that he might not even exist. He does, of course. And only weeks after Galliano’s first ready-to-wear collection for the house – duly rechristened Maison Margiela, both respecting its origins and acknowledging the stature of the great designer newly in residence – he spoke about meeting Margiela in person. “He came to my house in Paris and just started talking,” Galliano said in the Autumn/Winter 2015 issue of this magazine. “I didn’t really have to ask him anything. It wasn’t about whitewashing per se, but fingerprints and dirt, emotion and the passage of time. Why the Stockman dummy, why the white coats? There was nothing intellectual about it, he said. It was just about his aspiration to have a couture house. That was amazing. And he loved being backstage, how everything came together. What a special person. I have such huge respect for him, for the house that he built. How brave, how forward-thinking.”

Dig a little deeper, and the most remarkable thing about the meeting of Galliano and Margiela – the creative meeting of minds, not the physical meeting – is, in fact, the similarities, which may be unexpected but are undeniable. Both men are brave, both forward-thinking. Their talent was born out of a similar time – Galliano graduated from London’s Central Saint Martins (back then it was just Saint Martin’s) in 1984, when Britain was in the throes of Thatcherism and the merciless one-upmanship that went with it. Margiela is an alumnus of the Royal Academy of Fine Arts Antwerp. He graduated in 1979, becoming Jean Paul Gaultier’s first assistant in 1984. He showed his first collection in 1988, with designer fashion at the height of its broad-shouldered power but global recession looming. Both men are concerned with the construction, deconstruction and reconstruction of clothing, with a view to reinventing proportion and cut, both have a grasp of tailoring that is unprecedented, and both have been responsible for some of the most extraordinary, experiential fashion shows in history.

In the early days of Galliano’s career, the word luxury wasn’t overused in the way it is now. The notion of the brilliantly talented fashion designer living life for their craft, teetering on the brink of bankruptcy – or plain bankrupt – despite the beauty of their clothes, was not uncommon. It applied to everyone from Vivienne Westwood to Romeo Gigli. And to John Galliano. And out of such limitations, in Galliano’s case especially, magnificence came. In the early 1990s, disillusioned by the difficulties of running a fashion business in London, where he grew up, Galliano moved to Paris. There, with no money, he cobbled together a first collection by calling in favours, only to find that, despite critical acclaim, he was penniless again by the time the next one came around. After two shows in the French capital that caused a critical sensation despite (or, perhaps, because of) their lack of commercial viability, Anna Wintour helped him, forming a rare and intimate allegiance between editor and designer that continues to this day. Her contacts landed Galliano a backer and a venue: the crumbling mansion of the famed socialite and haute couture client São Schlumberger. The clothes were almost all black, most crafted out of the same bolt of material to keep costs low: it was satin-backed crepe. Galliano reasoned he could use the gloss and matt sides to make the clothes seem more complicated. Garments were trimmed with scraps of fabrics and embroideries from previous collections, accessorised with diamonds loaned by the great jewellers of the Place Vendôme. Reportedly, there were more security guards backstage than Galliano’s own staff. All this, whipped together in weeks, manifested itself in just about 17 outfits – but what outfits they were. Kate Moss, Christy Turlington and Naomi Campbell worked their magic for love, and Galliano’s position as one of the most important designers of the latter part of the 20th century was sealed.

Equally, the money Margiela made, even at his most influential – and he is now widely acknowledged as among the most influential fashion designers of all time – went back into his company. His distressed layers, unfinished hems, oversized proportions and repurposing of vintage and pre-worn pieces all continue to feel relevant, and to inspire new designers and new approaches. Today, Margiela is universally respected, even revered, but the collective fashion memory is a short one: when first shown, his designs were often perceived as attacks on the industry and received notions of beauty. When he was appointed creative head of womenswear at the venerable French maison Hermès in 1997, the establishment was almost as fazed as it was by Galliano’s appointment to Givenchy in 1995. The financial results of the seeds Margiela sowed were only seriously reaped by him personally once he sold a majority share to Only the Brave’s Renzo Rosso in 2002.

Galliano and Margiela are inextricably united in another way: they are key influences on younger generations of designers. From students taking their fledgling steps into the industry to nascent talents, to a few who are now well established and inspiring future generations themselves. Galliano and Margiela’s clothes, so different in so many ways, are alike not only in their power to shift fashion but to move people, emotionally. To bring joy. A Margiela show often remembered was for Spring/Summer 1990: it was staged in a playground in Paris’s 20th arrondissement, with each invitation created from illustrations by the children who played there. They were asked to draw how they saw a fashion show; later, those same children wound up walking alongside the models in the show, chaotically happy and spontaneous, watched by their proud parents and the community as a whole. A decade later, Galliano staged a show inspired by children playing dress-up, models in topsy-turvy layers of clothes, oversized shoes and a parade of hand-painted cardboard animal costumes that caused the normally stony-faced fashion press to break into gleeful smiles, laughter and applause. He called it Welcome to Our Playground. These shows were about more than parading and marketing clothes, and in turn the clothes were – and still are – more than just clothes. Their message expresses where we stand as a society, our value systems, our politics, and even what it means to be human. They still move people today.

The fact that Galliano now holds the keys to Margiela’s extraordinary legacy is a wonderful thing to anyone in love with fashion. Of all the people working in this industry today, Galliano perhaps, above all, prizes experimentation and honours craft. This is nowhere more evident than in the biannual Artisanal collections: inspired by haute couture and launched by Margiela in 2006, they are described by Galliano as the parfum – the pure essence – from which all else springs. Designed when Paris was in lockdown, this Autumn/Winter season’s Artisanal collection may be Galliano’s most personal to date. Shown in a film originally envisioned by Galliano, made in collaboration with the photographer Nick Knight for Showstudio and remarkable not least for revealing the exacting process behind the clothes, it references the show-off dress codes of the new romantic Blitz Kids – a young Galliano among them – the draping of classical sculpture and Italian Renaissance painting and traditional men’s tailoring. As raw as it is refined and as romantic as it is revolutionary, it is above all a celebration of the no-holds-barred creativity and imagination that arises from the adversity with which both Galliano and Margiela made their names.

EMAIL EXCHANGE BETWEEN JOHN GALLIANO AND ANOTHER MAGAZINE, JULY 2020

AnOther Magazine: You went back to your own beginnings with this collection – your work of the 80s, your formative ideas about fashion. Why did that feel right for now?

John Galliano: Compression and suppression inspire a distinct sense of creativity, resourcefulness. During the lockdown period, something drew my mind to the way we felt during the Thatcher years, our backs up against the wall. Nothing can stand in the way of this kind of creativity.

AM: Why was your 1986 Fallen Angels collection specifically a point of inspiration – what is it about that collection that resonated?

JG: In confinement, I had come across the neoclassical wet drapery of Antonio Corradini and Raffaelle Monti – these veiled heroines in marble – which really appealed to me. I was hungry for the kind of aspirational beauty that inspires hope. In many ways, we were expressing the same sentiment in the 80s. It was a hankering for beauty, for heroism, for hedonism and hope.

AM: Fashion has changed so much since that era – in large part through work you yourself have undertaken across your career, helping to reinvent the ways we see clothes and fashion as a whole. Why does that era’s aesthetic and spirit speak to you today? To hark back to another collection of yours, is it about rediscovering a forgotten innocence?

JG: Between then and now, the common denominator is resourcefulness. The motivations were different but the expressions are similar – working with what you have, you try to find hope through the beauty of escapism.

“I was hungry for the kind of aspirational beauty that inspires hope” – John Galliano

AM: The Blitz Kids were a slightly earlier reference, but also in the mix. Why is that pertinent to now? That idea of dressing up to party – a decadence, perhaps? Certainly a glamour.

JG: Zoom parties! Putting on a red lip for the screen. We may be in a time of limitation, but we still have a human need to dress up, express ourselves and have a good time. Glamour needs an audience. I’ve never referenced a period in my own life before, but the emotional state of lockdown evoked an energy I had felt before.

AM: Can you describe your feelings when you first walked into the Blitz? Do you have any anecdotes you’d be happy to share?

JG: I wasn’t queen bee at the time. I had not become the peacock people associate with John Galliano. I was still quite shy, on my foundation year at Saint Martin’s. But, working Saturdays at [the boutique] PX, I had met a girl named Maria. Her background was Spanish, we hit it off and she got me into the Blitz club, along with Princess Julia, who worked down the road. I was a bit in awe of these characters. Of course, I wasn’t ruling like the Stephen Linards and the Stephen Joneses – I couldn’t even afford to go every week – but I did serve some looks.

AM: Stephen Jones once said that people were embarrassed to be seen in designer clothes – apart from Westwood, actually – at Blitz, that people made their own clothes. Was that something you also remember and experienced? Why was that?

JG: I think it was in the spirit of the time. We didn’t have the resources. I remember I had a brown workwear suit, a two-piece, with asymmetric fastening and little gold studs on it. It had a blue contrast collar with an embroidered yellow oak leaf. And I probably wore some kind of pointed pixie boot. Charles, the manager of Mrs Howie [a groundbreaking boutique in London, opened in 1976 by future fashion PR Lynne Franks and her then-husband, Paul Howie], would sometimes let me wear a hand-knitted jumper that had the letter S, for Super, on it. In the Blitz, people would dress up as historical eccentrics. Resourcefulness became our gateway to self-expression.

AM: You talked about the theatrical costumier Charles Fox in the film you produced to show the Artisanal collection. Can you elaborate on that – what happened and what it meant to you? Many of the references – the military, the men’s formalwear – are still with you today, as is, undoubtedly, that spirit of reinvention and transformation.

JG: When Charles Fox closed down, all these amazing characters and Saint Martin’s students flocked there to buy it all up. Today, you might call it upcycling, but back then it was what they could get their hands on. If you have a love of theatre and history, reinvigorating the old is a reinvigorating process in itself. Creation is the very act of giving life to something.

AM: It’s interesting that you chose to reveal your creative process so openly in the film, from research, to narrative, to referencing, cutting and making and styling. That feels quite precious – a lot of designers keep it to themselves. Why did you decide to share that? Why is it right for now?

JG: The anxiety we all experienced during the lockdown period created a need for transparency. I felt a desire to be clear about what we stand for at Maison Margiela – our core beliefs in diversity, inclusion and self-expression – which all begins with the process work. By recording and showing our research practice, our genderless fittings and how we express ourselves through charity finds and upcycling, we reinforce those values in a way that might appeal to Gens Y and Z. It is my hope that when our clients eventually meander into a Maison Margiela store and see the results of that process, those values will resonate. Perhaps this format can be a blueprint for a new way of proposing our ideas and ethics.

AM: Your clothes always tell a story – often many stories interwoven. You find these extraordinary narrative references and they feed your creativity. Does fashion need to tell a story – does a narrative add to fashion, for the wearer – or is that your process, just for you as a creator?

JG: The narrative informs my research and the process work and the way I communicate with my team through that process. But in the end I often keep it to myself. During the creative process, however, it feeds into the values that are transmitted through our work and which create a connection with our clients.

“Between then and now, the common denominator is resourcefulness. The motivations were different but the expressions are similar – working with what you have, you try to find hope through the beauty of escapism” – John Galliano

AM: What was it like designing a collection during lockdown? What were the good things, what were the bad things? How did the process change? And do you feel it has changed your creativity – your viewpoint on the world?

JG: In the beginning, it filled me with anxiety – and like everyone, of course, we had to deal with practical challenges. To me, it became a matter of turning those challenges into a sense of resourcefulness. I applied some of the things I’ve been fortunate to have been taught in the past. It’s like a mourning period – once you accept reality, you are able to embrace the unknown. And so it became a driving force – the feeling that nothing would stand in the way of creativity.

AM: Given the current situation, people are speculating that the collective experience of the fashion show may be a thing of the past. You have staged some of the greatest fashion shows in history, redefining the medium. What is your reaction to the idea that fashion shows may be of the past? How important are shows to you, as a means of expressing your ideas?

JG: What I eventually realised during the lockdown period was that fashion as we’ve known it in the past will never be the same, at least not until a vaccine is found. For the moment, I hope the format we adapted to this season can be a new way of communicating and exploring one’s collection. I don’t really like doing those big shows any more, because so often the focus is taken off the clothes. I prefer smaller shows. For now, I’m happy treading gently in this new direction.

AM: Our fight and flight instincts have perhaps never been so acute, and both those elements are present in the collection. The confrontation of taking clothing apart at the seams and the romance and fantasy of veiling, clothes that appear drenched in water. Does that make sense to you?

JG: The idea of fight and flight is another way of expressing resourcefulness and escapism – elements that have been inseparably interlinked through history. The human desire for beauty and seduction is a powerful instinct.

AM: When it comes to difficulties, do you feel that you, as a designer, propose clothes to fight in, or clothes as a flight of fantasy, an antidote to reality? Which do you find more powerful?

JG: I have spoken before about our desire to transmit Gen Z’s appetite for defiance through self-expression as a reaction to conformism and the societal preconceptions that negate our authentic selves. My proposals reflect those values. I hope our work can be tools for the expression of individuality and a message of joy and hope.

AM: In the film you showed predominantly classical female veiling. Did you look at veiled men in classical sculpture too? In some ways that has always been more scandalous, the naked Christ.

JG: Historically, the wet drapery that inspired me was often related to images of goddesses – and gods, too. During the process work, I began to express it in these celestial bodies – heroines as well as heroes – which draw the mind to many areas of mythology. You’ll recognise it in how I christened each passage in the collection, and in [model] Malick’s performance in the film.

AM: How does that religious iconography relate to your childhood?

JG: It’s a familiar element of my upbringing, because my mum brought it from Gibraltar and Spain. But this collection is reflective of so many mythologies.

“The human desire for beauty and seduction is a powerful instinct” – John Galliano

AM: You are a person who has often had to deal with a lack of resources and has somehow managed to turn those limitations into a positive. The São Schlumberger collection, for example. How – and why – does limitation inspire you?

JG: Limitation creates challenges, and challenges force us to innovate. Whether inspiration is born out of necessity or out of determination – such as a desire to be sustainable – it inevitably enriches the creative process.

AM: There’s always a conversation around the relevance of haute couture – people argue that it is moribund, anachronistic, and so on. In what way do you feel you have moved the Artisanal so it works for now?

JG: I work within a creative pyramid, the pyramidion of which is haute couture. The work we do in the Artisanal atelier – the experimentation, development and technical know-how – drip-feeds into every other collection at Maison Margiela. Haute couture isn’t an expression of elitism, it’s what fuels a fashion house. It is the highest and most authentic form of dressmaking, and in an age tuned into transparency, I think the role of the dressmaker will be re-evaluated.

AM: And why genderless? That also goes back to the Blitz, perhaps?

JG: Genderless-ness is part of our genetics at Maison Margiela. It goes back to the freedom of self-expression and breaking down preordained conformist ideas of masculinity and femininity. Without these societal preconceptions we are free to express ourselves, to discover new things and evolve. The Blitz club, like certain communities today, provided an escapism from societal norms, but so many people are still having to negate their authentic selves. There’s still work to be done.

AM: There is still an amazing sense of the emotion in clothes that are hand-sewn for days, even weeks, on end, the romance of the touch of the hand. It feels very much as if you own that territory and that there are not so many people doing it like that today. Can you expand on that a little please?

JG: Over the years, I have taken on the responsibilities of a creative director, and I accept the role. But I am, at heart, a dressmaker. The creative process is the fuel of fashion. And creativity is the blood that courses through my veins and through this house.

AM: Craft is incredibly important to what you do – and always has been. It feels integral to your idea of couture. What does handicraft represent now, in a time when it is more difficult for many people to be together?

JG: Someone who watched the film told me that the connectivity between the team really shines through. That meant a lot to me, because connectivity is created by authenticity – and there’s nothing more honest than craftsmanship.

AM: There’s also the idea of construction and the extremely technical pattern cutting involved in this collection specifically. Can you talk a little more about the circular cut? About the methods you explored in these clothes, this collection?

JG: I mentioned how I was hungry for an aspirational beauty that creates the same sense of hope I remembered from the Blitz years. Back then, I had discovered the bias through a technique I had developed called circular cutting. It’s a way of structuring garments from several circular pieces – in this case, fabrics like butter muslin and thermocollant – which diffuse the draping and can evoke that wet, chiselled effect. The tailored pieces are examples of Recicla – humble charity-shop finds that I reinvigorated with heroic cutting – rooted in décortiqué, inspired by the hedonism of the dance L’Apache, which conjured these armour-like silhouettes. That process reminded me of the resourcefulness of the Blitz era.

“The creative process is the fuel of fashion. And creativity is the blood that courses through my veins and through this house” – John Galliano

AM: You talk about the idea of a community, the Margiela pluralism of ‘we’. Do you think that is a more humane position than, for want of a better way of putting it, the concept of the designer superstar? You have experienced both – in a sense, you have epitomised both.

JG: It is my hope that the film reflects the sense of community and connectivity that exists within the pyramidical structure of our fashion house.

AM: You have always had your own community. You can really see that in the film. These are all people who have been with you for a long time, some even from the start. They seem like kindred spirits – is that important? Finding people you can communicate with instinctively, maybe even without words?

JG: Community is about sharing and connecting, becoming part of a unity and relating to one another through emotions rooted in mutual memories. As you see in the film, we share all these things and use that connectivity in the creative process.

AM: In general, what is the importance of teamwork – of community – in fashion? Does it feel more important than ever now, following the assault on our personal freedom and contact with other human beings that the pandemic has brought?

JG: The lockdown period demonstrated the human need for connection. Immediately, we all took to Zoom and other channels to invoke a sense of connectivity. Fashion has the power to express codes of belonging. Through the values we have reinforced this season, I hope we are able to communicate the ethics of our community – the values of Maison Margiela.

AM: I think perhaps people don’t always realise the many connections between yourself and Martin Margiela – the importance of white and clothing stripped back to the toile, the interest in 18th-century cut, the deconstructing and reconstructing of traditional garments and the value of a sense of the passing of time, of age. How do you feel your two aesthetics relate to one another?

JG: When I met with Martin shortly before I joined the house, as a couturier I was particularly interested in his adaptation of the codes of haute couture – the idea of the maison, the white coats, the genetics, and so on. As we continue to establish a new set of codes at Maison Margiela, I hope those parallels feel inherent.

AM: You have launched a Recicla collection as part of the ready-to-wear and the Artisanal, where you source vintage items and rework them. That, again, references the Maison Margiela Replica heritage, but it is also a gesture towards sustainability. It’s an overused word but why is it important and can fashion ever really be sustainable?

JG: Upcycling, the raison d’être of Recicla, is a self-evident proposal for sustainability, but one that invigorates the creative process at the same time. Recicla started its life in the Artisanal atelier but is now being embraced by our commercial teams and actively going into stores, and I’m so happy to witness this development. Step by step, we can all play our part in being resourceful and reducing waste.

AM: You are among the most-referenced designers in student and emerging designers’ work. Does that make you happy, even proud? It’s not easy for you to answer, maybe, but why do you think it is?

JG: If I can deliver some of the hope, aspiration and passion that I remember from my own time in college, it’s a joy. Every year, when our new lot of stages arrive from the colleges, I do a dinner for them and get out my finest china and crystal. Sometimes it’s a drag ball or a karaoke. We have fun. When they come here they’re no different from how I was. Their experiences today are different because of the internet, but they’re creative souls like we were.

“Fashion has the power to express codes of belonging. Through the values we have reinforced this season, I hope we are able to communicate the ethics of our community – the values of Maison Margiela” – John Galliano

AM: There’s that old cliché of money being no object. In many ways, the most brilliant fashion proves and disproves that. How would you look at that sentiment, given the value of experience/hindsight?

JG: Financial resources make a difference to the way in which ideas can be executed and communicated. But some of the finest ideas are born out of a lack of resources. Drive can be fuelled by desire, but also by necessity.

AM: What would you say to a student starting out? I feel that your words would be very important to them, given the challenges facing any young designer, but perhaps more than ever now.

JG: Believe in yourself. Believe in your dream. Be passionate. You can be whatever you want to be. Don’t listen to anybody who says you can’t. Work hard and never give up.

AM: What are your hopes and dreams for fashion as we emerge from this crisis? And what are your hopes and dreams for the world?

JG: Now, more than ever, we need to respect fashion as a platform for communicating our values and ethics. As we emerge from this crisis, it is our responsibility to stand up for what we believe in – inclusivity, diversity, nonconformity, self-expression. We have to use the voice of fashion for positive change.

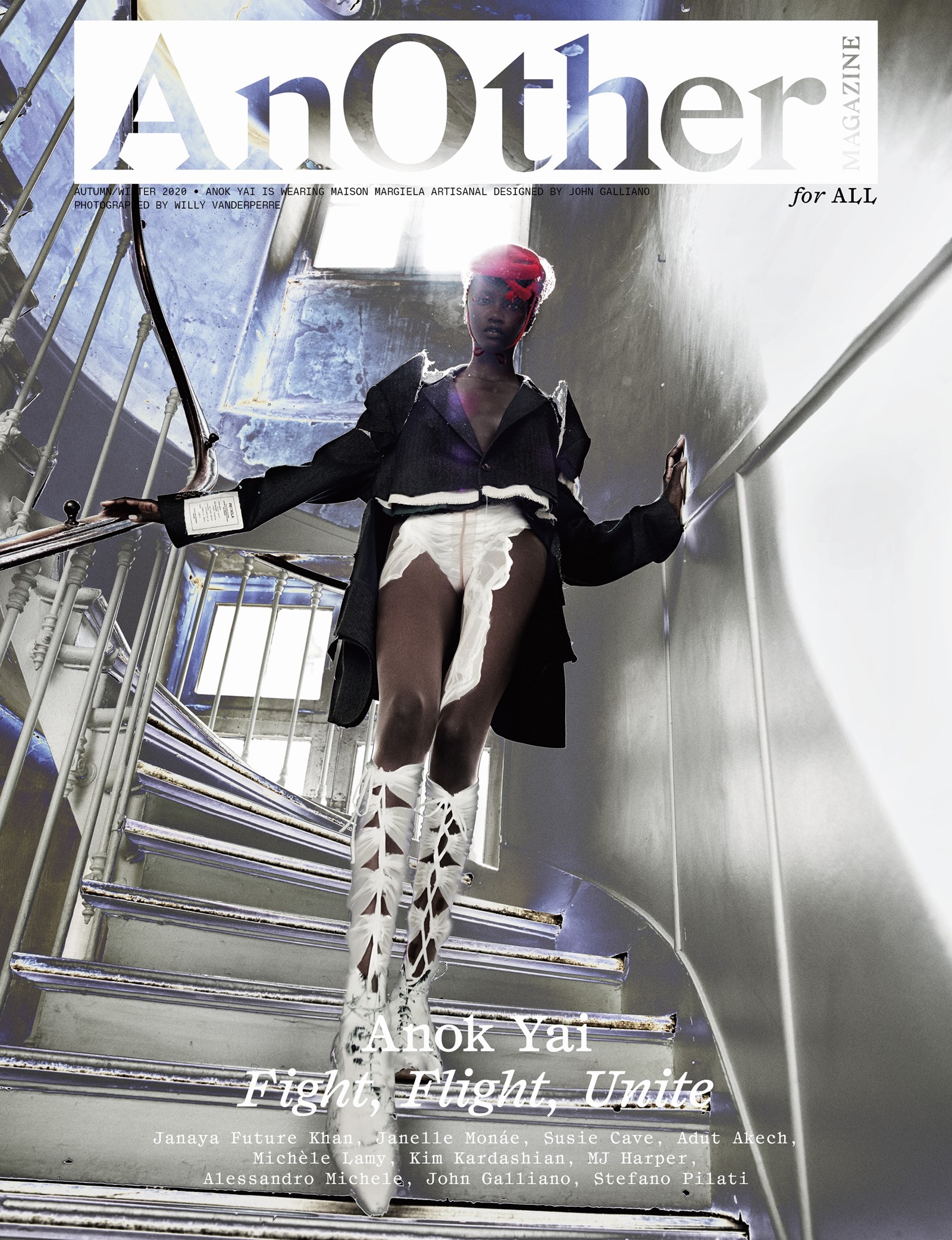

Hair: Anthony Turner at Streeters. Make-up: Lynsey Alexander at Streeters. Manicure: Delphine Aïssi. Casting: Jess Hallett at Streeters. Models: Anok Yai at Next Management, Niki Geux at Premium Models, Daan Duez at Rebel Management, Lennert de Lathauwer at Hakim Model Management, Malick Bodian at Success Models, Anton Engbrox and Abdoulaye Diop at Marilyn Agency and Fedor Diakonov at Tomorrow Is Another Day. Lighting technician: Romain Dubus. Digital operator: Henri Coutant. Lighting assistant: Corentin Thévenet. Styling assistants: Niccolo Torelli and Aline Mia Kaestli. Hair assistants: Claire Grech and Blake Henderson. Make-up assistants: Phoebe Brown and Miki Matsunaga. Production: Entrée Libre. Producer: Floriane Desperier. Production assistant: Jeremie Spada. Post-production: Stéphane Virlogeux. Special thanks to Raffaele Ilardo and his team, Alexis Desilva and Pauline Abadia at Maison Margiela Artisanal and to Harry Wicks.

This story originally appeared in the Autumn/Winter 2020 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is one sale internationally from October 2, 2020.