One of fashion’s most independent and visionary minds, Helmut Lang’s utilitarian designs came to define the 90s. This year, just as that decade becomes ripe for reappraisal and Lang’s contribution seems more relevant than ever, his archive burned down. Here, we present an exclusive selection of Lang’s work and Susannah Frankel enjoys a rare interview with the fashion designer turned artist

It is surely more than a little ironic that just as Helmut Lang’s signature is more heavily referenced than ever, and his original designs are among the most coveted the world over, the former fashion designer’s own archive has – quite literally – gone up in smoke.

“Yeah, it’s like in Lost – swallowed by the smoke monster,” Lang laughs, putting what might be described as an unusually brave face on it, although history is testimony to the fact that he is not one to dwell sentimentally on the past.

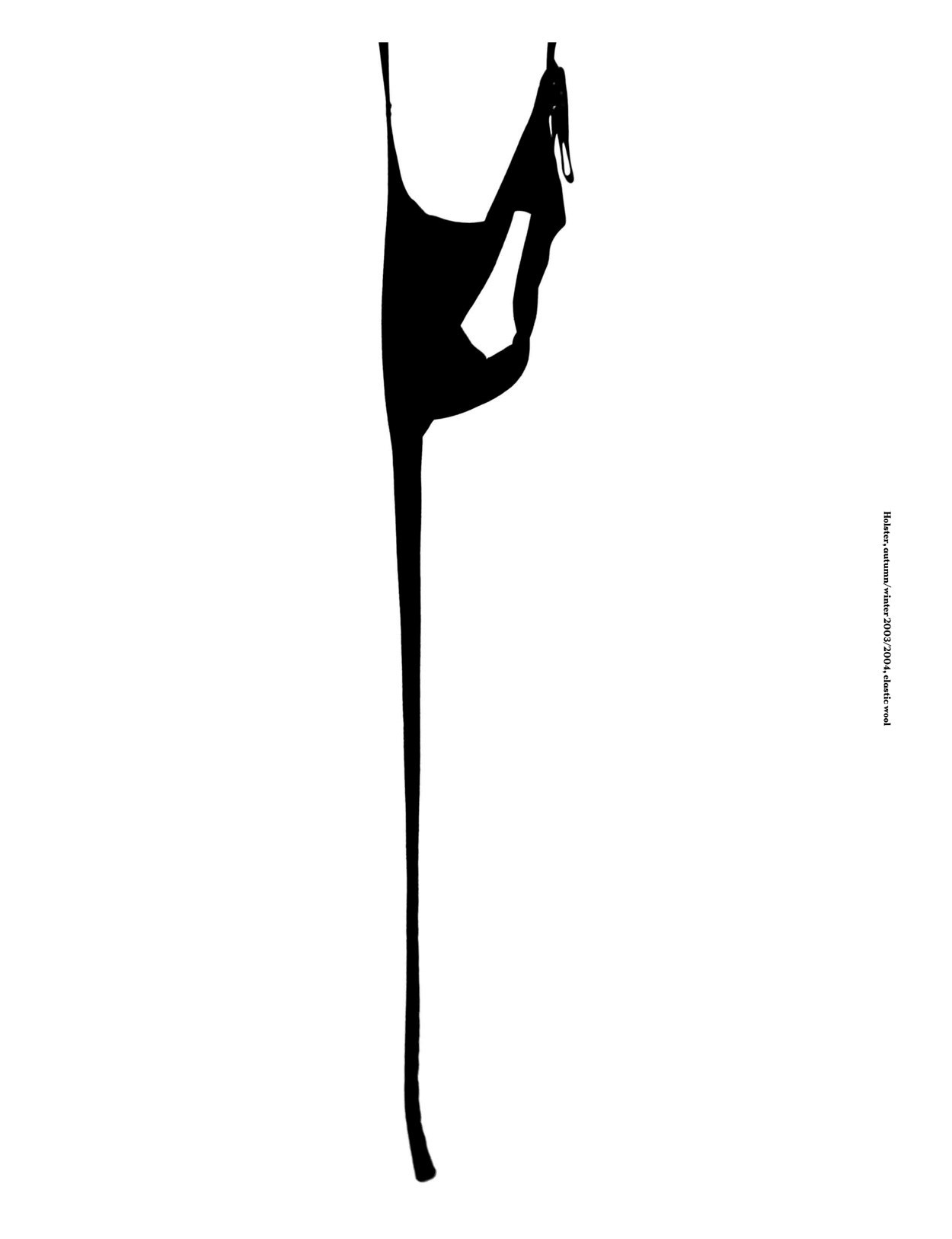

“The studio is in the same building where we originally had the store and the headquarters,” he says. These days, Lang is pursuing work as a fine artist which, to date, has included collaborations and group exhibitions with friends Louise Bourgeois (“I think of her every day”) and Jenny Holzer and, more recently, solo shows in New York, Hanover and Berlin. Back in the 1990s, however, Helmut Lang, located at 80 Greene Street, in the heart of Downtown New York, was the place to travel for some of the world’s most innovative and inspiring designs. Lang’s handwriting not only influenced what women – and indeed men – chose to wear on a daily basis; it was also continuously directional and, more unusual still, entirely heartfelt. The fusion of an openly emotional, determinedly human and profoundly idealistic viewpoint, with a rigour and modernity that was unrivalled, set him apart, now as then. Then there was the fetishistic, at times deliberately unsettling streak that ensured that there was nothing even remotely bourgeois about this aesthetic: the uneasy fabric combinations, fine jersey bound to the body by thick strips of elastic, flesh-baring gashes at elbows and shoulders, fluttering ribbon disrupting the otherwise clean lines of the clothes … It should come as no great surprise, given the current climate, that any Lang-inspired designers – and there are many – have cleaned up the latter in particular. The raw power that his fashion heritage also signifies is not so high on the agenda for the current generation, which is clearly interested in both his designs and method of presentation. Theirs is a more polished vision, if you will, as best befits these luxury fixated times.

With the 1990s ripe for reappraisal and labels like “minimalism” and “utilitarianism” gaining currency as buzzwords once more – albeit with the word “new” preceding them – a multimedia exhibition celebrating that era opens this month at the MMK Museum of Modern Art in Frankfurt. When we speak, Lang has just begun working with another old friend, Juergen Teller, on an installation for a room there that will include the designer’s sculpture, Front Row, part of a project commissioned by Dakis Joannou, which refers to the bright, white warehouse space at 17 Rue Commines in Paris where he showed for years. Photographers and artists Vanessa Beecroft, M/M, Corinne Day and Wolfgang Tillmans among others will also be featured.

Ask Helmut Lang why the period in question appears to be so appealing right now and he says: “Retrospectively, I guess it was about establishing a new visual language. None of us had enough money to produce the kind of images that were around at that time so it was like a support system to enable us to find a way to express ourselves. There were certain restrictions when we started out and we worked within those to create a new taste level. With less possibilities came newness.”

Lang’s determinedly lo-fi presentations, referred to as Scéance de Travaille – work in progress, in acknowledgement of this being a continuing exploration of a certain aesthetic as opposed to isolated, one-off events – were a case in point. At Rue Commines, Lang mixed women’s wear with men’s wear – this too was a first – and eschewed any elaborate backdrop or raised platform in favour of concrete pathways along which models stormed at ground level rather than striking theatrical poses. In a way this was as close to a vignette of real life existence as a fashion show had ever come – real life at its most beautiful admittedly. Said models only added to that effect. The big names of the day were all present and correct of course – Lang’s shows were always a high point on the Paris schedule – but he also cast his friends, different age groups, and varied body shapes.

“The runway?” he remembers. “It was less dramatic than for a Mugler or Montana show, for example. That was a stage and the clothes were made for a stage. Our fashion was not for the stage. It was for wearing. The same thing happened with the images from that time.”

Claims that Helmut Lang fell in love at first sight with the aforementioned Teller in a public convenience in Vienna in 1991 are unsubstantiated – or, “I made that up,” as the photographer now puts it. “We met at the beginning of the 90s in Paris at the shows and started working together in 1993,” Teller says. “We liked each other right from the start. I was really drawn to Helmut’s manner, to his way of being. We both spoke German which was unusual and, for me, it was really extraordinary that some guy from Vienna was making noise in Paris.”

Any personal connection aside, Teller also saw Lang’s process as ideal subject matter for his own work. From that point forward he began shooting backstage at Helmut Lang each season – back then such access was unprecedented – going on to produce some of the designer’s most memorable advertising campaigns, pioneering, amongst other things, the use of images that were ready made.

“We were young and didn’t have any money or anything,” Teller remembers. “It was difficult for Venetia [Scott] and for Melanie Ward and for all those people in the early 90s to do the stories and get the clothes. Half of it was from Portobello Market and thrift shops. Only a few bits and pieces came from fashion designers. It was a completely different time. We just did things because we wanted to do them and because it was exciting.”

Teller also confirms that any appeal was rooted in Lang’s entire approach and not only the clothes. “Backstage at Helmut’s shows, there were suddenly all these supermodels, these fantastic looking girls and I was right there with the chance to photograph them,” he says. “I think Helmut was doing something modern, something new, something you hadn’t seen before. The whole package was very important. Where he showed it, how he showed it, the music, the casting … There was this buzz and excitement, the girls were nervous, maybe, Helmut was nervous. The way six months of work was over in ten minutes, that was brilliant too. It was a better way of capturing what he did than using the clothes for a shoot set up in a studio. It was much more real.”

In 2000, Anna Wintour commented on Helmut Lang’s impact thus: “Helmut came along and at first it was ‘Wait a moment, what’s this? This is not the spirit of the mid-80s’ – which was all about opulence. But then everything crashed and fashion reflected that and Helmut was there to take advantage.”

“It is a bit too late to question the internet. It is here for better or worse and it magnifies the informative and visual chaos we are dealing with right now” – Helmut Lang

Given the excesses of the first decade of the new millennium and the crash that likewise followed, a renewed interest in Lang’s work is only to be expected, then. However, the fact that his designs appear just as relevant, just as contemporary, now as they did then is more remarkable. There is none of the telltale period detail that dates the work of lesser designers leading inevitably to the conclusion that Helmut Lang is that rare thing, a visionary, ahead of his time in almost every way. Even our all-consuming love affair with the internet was foreseen by Lang years before the rest of the world caught up with him. He made the decision to live stream his Autumn/Winter 1998 collection online only days before it was shown, having relocated his business from Vienna to New York a year prior to that, acting, as he says he mostly does, “on instinct”, and presumably without realising quite the power the then relatively new medium would soon wield over the fashion industry and way, way beyond that.

“It is a bit too late to question the internet,” Lang says more than ten years later. “It is here for better or worse and it magnifies the informative and visual chaos we are dealing with right now. But it also enables great opportunity for so many people who are not in an urban environment. As with all radical changes in society, it will be accompanied by a set of ugly transitional circumstances. Ultimately, the future will be a progressed landscape with intriguing possibilities and the reality is that some will gain and others will lose. There is definitely no way back so we will consequently embrace the outcome and contribute all the good, human qualities we can. We will have to choose whether to be wise and responsible – or foolish.”

For Spring/Summer 1999, bucking the system once more, Lang announced that he would be showing in New York a good six weeks in advance of the official schedule and before the Milan and Paris collections. It is a measure of his impact that more than a few other big name American designers followed suit resulting in the New York shows being moved permanently. They now kick off the international fashion caravan as opposed to closing it.

“I think Helmut changed rules that were so embedded they weren’t even recognised as rules,” states the creative director, curator and writer Neville Wakefield, who worked with Lang on his first solo art exhibition, Alles Gleich Schwer, literally translated as “all has equal weight”, in 2008. “His reshaping of silhouette and its relationship to modernism, utility, sex and sentience was one aspect of that but he also tore down the temple of its presentation. He shifted the calendar, introduced the idea of the internet to fashion presentation, the ready-made image to fashion advertising – most of the things we now take for granted were gestures that seemed virtually unthinkable at the time.”

Helmut Lang sits on the side of the fence that decrees imitation is the most sincere form of flattery. In fact, nothing much seems to rattle this apparently serenely contented figure who, it is well known, sold his company to the Prada Group in 2004 and then walked away from it. The Helmut Lang trademark was later acquired by Link Theory Holdings which owns it today.

While insisting that it is no longer his place to comment on the workings of the fashion industry, Lang will speak of the corporate nature of society in general. “In a way, what has happened in the recent past with vast expansion and globalisation, and greater access to luxury and creativity, is that the system has become much more vulnerable and has been eclipsed by the importance of economic data,” he says. “The equation now reads money is making taste rather than taste making money. The result is an environment where one doesn’t really know what is what, and where more also means less rarity.”

Looking back: “I am proud that I was responsible for a body of work that is still contemporary and influential. But it is also important that a new language is formulated because the times are clearly demanding it.” As Wakefield argues, “What I see in terms of referencing is more of a stylistic quotation of the more monastic uniform driven aspects of the Helmut Lang aesthetic than any attempt at the kind of paradigm shift that he instigated.”

“Even in fashion, it’s not all about silhouette,” Lang confirms. “It is also very much about the entire idea of reflection and there is an invincible borderline where fashion is not only fashion but becomes an evident expression of an era.”

“I am proud that I was responsible for a body of work that is still contemporary and influential. But it is also important that a new language is formulated because the times are clearly demanding it” – Helmut Lang

Even so, there is little more evidently expressive of its time than the aforementioned Helmut Lang archive. “It’s on the third floor,” Lang explains. “Our studio director got a call in the middle of the night on February 18th this year to say there was a problem, then 200 firemen turned up along with the media and the Red Cross.” He says this almost as if it were an everyday occurrence. Suggest that it is, in fact, nothing short of calamitous in a burning of the books/Kafka-esque kind of away and Lang says deadpan: “Don’t be too dramatic. I’m thinking you’re more dramatic than I am. Please get that out of your head.”

As luck would have it – or “sometimes it’s crazy how things work out”– Lang’s team had previously spent months going through 1,000s of pieces dating, for the most part, from the late 90s onwards, and donating them to museums around the world. “Prior to that period we didn’t ever really keep an archive,” he says. “I never wanted one and we needed the money so we sold the samples or paid models in clothes.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, the Costume Institute in Kyoto, the Musée de la Mode et du Textile in Paris, MoMu in Antwerp, LACMA in LosAngeles, the Groninger in the Netherlands and more all now have a (thankfully undamaged) selection of his designs from the latter part of his career at least for posterity.

Moreover – and this too is typical – Lang now views the transformation of his hitherto well-preserved legacy with not only pragmatism but even optimism. He intends, he explains, to use some if not all of it – there still remains between 7,000 and 8,000 pieces – as raw material for future projects just as he did, to name just one example, the letters and other documentation he kept over the years for his ongoing Selective Memory Series. Of this project, Lang has said that the abstract appearance of the notes when placed alongside one another was the point of the exercise over and above any focus on their content. Even so, it is hard for anyone with even a passing interest in fashion to resist reading notes written by everyone from Roman Polanski (“never mind the awards, I looked smashing, didn’t I?”) to Bruce Weber (“the clothes for dogs are so great that I can’t wait to see them wearing them”) and from Carine Roitfeld (“thank you for my handcuff … I’m yours forever”) to Donatella Versace, who addressed an invitation to “Helmut baby”.

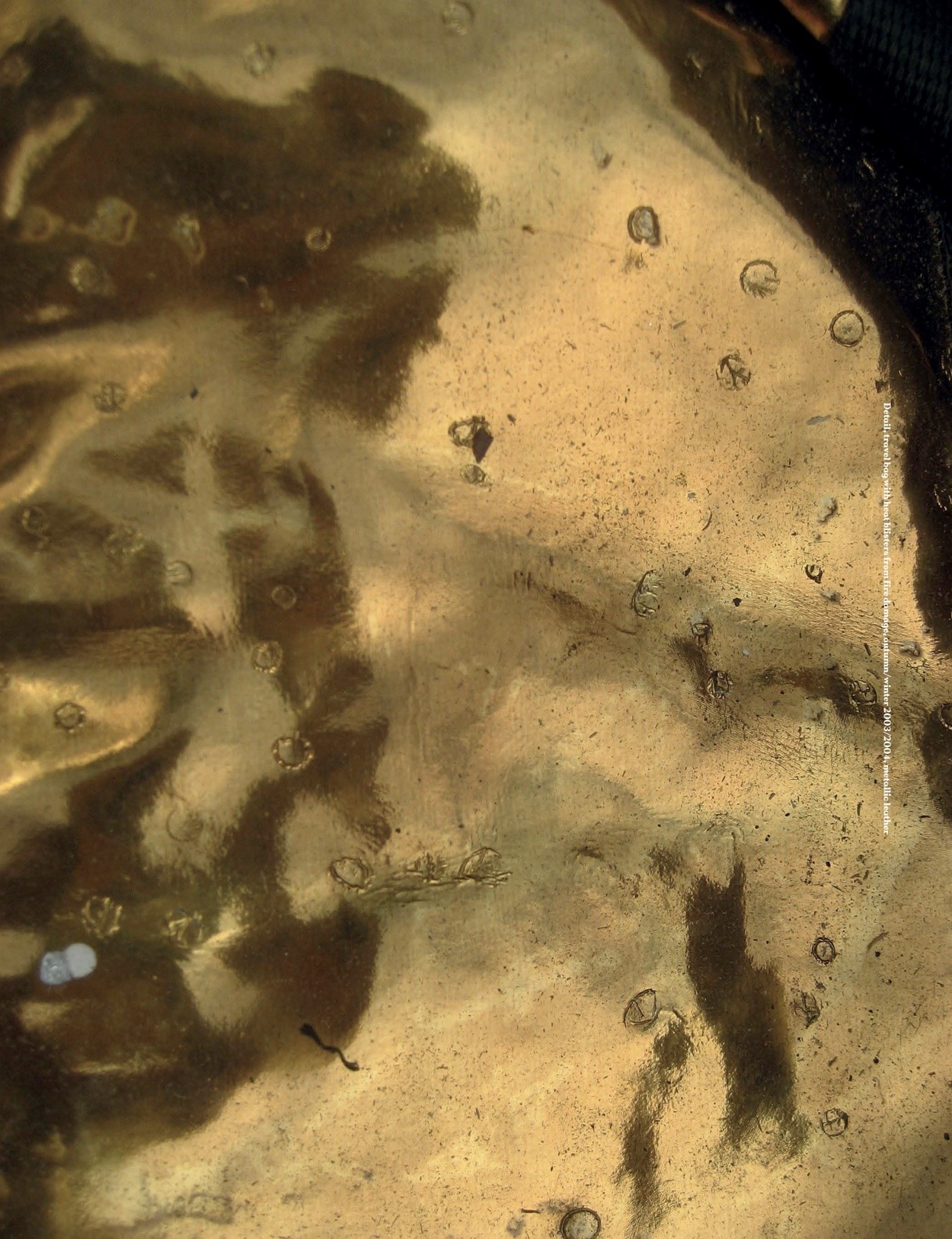

“My history sometimes informs my current work,” explains Lang, “as it is part of my memories. I also used found objects in fashion. [Spray-painted vintage cowboy boots, antique embroideries, necklaces with their gemstones removed and bottle-top buttons all played their part.] Obviously, there’s a very emotional side to me but I definitely don’t think yesterday was better because that’s just pointless. Once in a while, of course, that’s fine but as a general concept I think we have to live in the present and the past is about experience with which to live a better life now. You know, there’s one shoe from the archive, for example, that’s completely burnt and it has become a different form because of that, but it actually still looks great. It seems to meas if that is an acknowledgement of the transformative power of the fire, that it’s about destruction but it still looks beautiful. I said some years ago that I work on something and do it as well as I can and then, when it’s finished, I hand it over to the public and they do what they want with it. The fire did the same with certain pieces and I find that pretty interesting.”

“Helmut’s an aesthete who believes in the creative energy of destruction,” says Wakefield. “Whether in fashion or art he’s always working with the friction of opposing elements.” More specifically, perhaps: “I think the fire damage is a kind of collateral expression of his ambivalence towards his career in fashion. The archive represents Helmut’s cannon and I suspect he doesn’t want to be canonized. Like Ed Ruscha it maybe a question of ‘I don’t want no retrospective’. It may be that he’s more interested in burning his career than preserving it.”

Born in Vienna in 1956, Helmut Lang is known for dressing cities but this belies the fact that he spent most of the first ten years of his life in relative isolation in the village of Ramsau am Dachstein in the Austrian Alps.

“I caught up late,” he said when we first met in Paris way back when. “I was a late teenager. If you start out with less, you eventually have the possibility to experience more, you have a greater evolution in front of you than someone born into a wealthy environment. There was no TV. It’s not that I’m that ancient, you know. I didn’t read particularly. I guess that these days people are more impatient, children start reading when they’re six. If you grow up in the country you know how nature works, you understand the cycle of things. It was just about life which is the most important thing anyway.”

Lang lived with his maternal grandparents at that time, following the divorce of his parents – his mother subsequently died. “In the mountains, there was a very elegant way about basic necessities, a great beauty in a certain way that is completely refined but not about money,” he told John Seabrook in the New Yorker in 2000. “People who grow up in the city don’t have that sense of taste, they don’t experience it as connected to real life, to nature, as I did. I was really lucky to have that experience, though I was perhaps unlucky that my parents' divorce and my mother’s death made me have it.”

“I think that I was always armed with my own vision and I’m prompted by the desire to find the true form for whatever I am working on” – Helmut Lang

If there is more than a touch of the fairytale to these beginnings, the dark side of that genre was soon at play once more. Lang’s father remarried, at which point he was taken to live with him and his new stepmother in Vienna and was forced to wear cast-offs from her dead father’s wardrobe. Given that the latter was a Viennese businessman this was highly structured and formal and so, one can only assume, young Helmut Lang cut quite a dash. “No. I was like Edward Scissorhands,” he says. “I just felt very odd. I didn’t want to leave the mountains. I would have preferred the world to be flat and high, that’s where I grew up, and not so round. I had a bad time in Vienna for a few years with my stepmother and father and I moved out when I was 18 and started out on my own.” He never spoke to his father, who died some years ago, or his stepmother again.

As is often the case for those deprived of the opportunity to express themselves stylistically in their formative years, out on his own Lang made the most of things describing his appearance thereafter as “overdressed, a major mistake – definitely completely wrong.” More than that, he will not be drawn. In 1977, however, he started creating his own, more pared down wardrobe in a made-to-measure studio in the Austrian capital and was soon making clothes for friends and acquaintances too. “I never chose fashion as a career,” he explains. “It started as an accident and I made it a career. I didn’t have much choice but I am thankful for that now. I have never separated work from life and I have never really known any other way.” Over the next 25 years this approach gave rise to one of the most respected fashion houses of the second half of the 20th century. By today’s standards, this was a highly considered – as opposed to meteoric – rise to fame, however, and one that was almost entirely uncompromised.

“I think that I was always armed with my own vision and I’m prompted by the desire to find the true form for whatever I am working on,” Lang says. “I don’t think compromising creativity has pushed anything forward – only independent work and independent minds have done so. I’m really not applying this to a designer in particular but to anyone who wants to do something creative. If someone does want to establish their own fashion house, though, and have the freedom to independently pursue their own personal vision, that comes with a set of consequences. It will take a long time and it won’t bring instant fame – definitely not money – for quite some years. Circumstances at the moment militate against the independent designer as it seems really hard to resist money. There is a high expectation for everything to be instant which, naturally, comes at a price. You cannot blame the establishment for that because revolution doesn’t start from the top. That much is clear.”

Much has been made of Helmut Lang’s decision to spend a good part of his time today at his Long Island home, far from the madding crowd, as it were. The designer turned artist has returned to the isolated environment of his early years, it is said. It’s safe to assume that this is a somewhat romanticised view, however. In reality, he is based as much in New York, where he also has his apartment and studio, as he is by the ocean and is surrounded by an intimate circle of friends and collaborators just as he always has been. Away from the endlessly sedentary world of the fashion designer’s studio he is now bronzed and buff and has even cut his trademark hair. “It was time. And it’s so much easier, life, without a blow-dry,” he laughs. “It changes everything.” But, for the most part it is business as usual.

“Remember, for a long time I had my studio in Vienna which, really, compared to London, Paris, Milan and New York is not urban. I have always preferred to work in an environment where it is quiet and less distracted. Then I need the urban environment to present mywork, to exchange and animate it and have feedback and I really enjoy that.” Lang describes himself as “border-less”, clearly comfortable with his Austrian roots and the way that his time in Paris shaped him. “Obviously I settled here [in the US] and this is my home but I feel like I’m part of everything. I never understood, for example, when Austrians leave Austria not wishing to be there anymore, and then regroup in London, New York, or wherever, and do their own little Austrian thing … Do you know what I mean? Don’t leave.”

In his latter days as a designer, Lang eschewed the social shenanigans surrounding the fashion industry and famously declined to pick up no less than three CFDA awards in person. Today he takes this one step further, not even attending his own openings. “I never felt comfortable with public mass exposure,” he says, “but in fashion I had to be there and backstage. It was part of the process. With art, I don’t have to, so I take chances.”

It is genuinely heart-warming to find that the chances that Helmut Lang takes – and has indeed always taken – have paid off. If anyone deserves their moment in the sun – quite literally – it is he. It is almost unprecedented, after all, to emerge from today’s increasingly fierce system with integrity, a legacy, financial independence and a life beyond fashion and that is just what Lang has achieved. Not that there is any question of his ever resting on his laurels. For now he works as hard as he ever did, applying just the same approach to his art as he once did to fashion.

“I talk to him often,” says Teller, “visit him in Long Island, we’re really close, he’s a friend of the family. When we speak, we still struggle to make sense of the industry. When I see how people today have to work, how much commercial strain they’re under … My goodness me, I don’t know how they do it. I think Helmut was really clever. He made money out of fashion and now I think you absolutely feel his hand in his art. When you’re in front of it, you feel it very strongly.”

“Emotionally, it is the same approach, the same struggle to wrestle with an unknown beginning,” Helmut Lang says. “To apply pressure to oneself means to care about what one does. I always want to be my best and I never expect things to be easy along the way. In that sense, it doesn’t matter what I do.”

Visuals courtesy of hl-art.

This story originally appeared in the Autumn/Winter 2010 issue of AnOther Magazine.