In 1996, Glen Luchford’s first campaign for Prada was unveiled to the world. It was a monumental moment for the brand and photographer – but also, more significantly, for the wider fashion industry. Luchford’s evocative, cinematic visuals broke the mould of the typical designer campaign, and helped introduce a new era of bolder concepts and bigger budgets. His most famous shot for the brand – of Amber Valletta reclining in a boat on Rome’s River Tiber, at dusk – is the perfect example of his immersive flair.

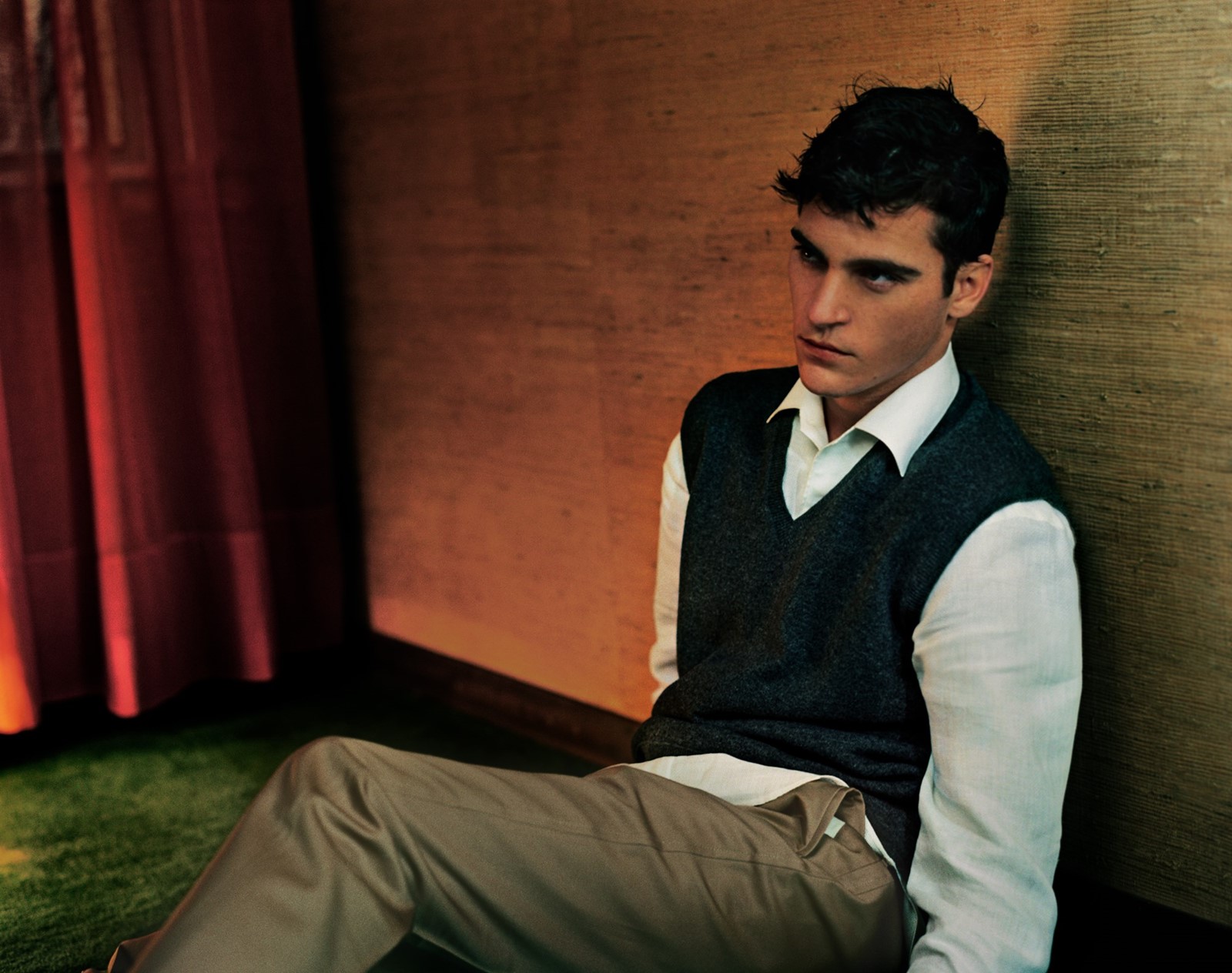

Now, over two decades on, the photographer’s work with the brand is being celebrated in a new book from IDEA. In PRADA 96-98 by GLEN LUCHFORD, readers are treated to a collection of shots taken during the campaigns of the late 90s. It features Luchford’s portraits of Valletta, as well as his work with Willem Dafoe and Joaquin Phoenix (both of whom have featured on the cover of Another Man), who both served as Prada ambassadors during the decade. It is, in the words of publishers IDEA, “possibly one of the greatest fashion photography books ever made”.

The book also features an in-depth interview with Luchford, led by writer and curator Lou Stoppard, which sees him discuss the inspirations behind the campaigns, as well as how much has changed in the years since their release. You can read an exclusive extract below.

Lou Stoppard: Why this book, now?

Glen Luchford: When I look at those Prada pictures, they really describe to me in pretty precise detail how much the industry has changed since then. It came flooding back to me what a seismic shift everything has gone through. It’s interesting because Miuccia has also just made a pretty seismic change in the running of the company, by hiring Raf Simons, so it feels like it’s the end of a chapter maybe, and, of course, the beginning of a new one.

LS: Those pictures feel like a real marker of time for so many reasons; some around the commercial cycle of fashion, but also photographically, in terms of a shift from film to digital. It’s a very interesting moment, just prior to the widespread adoption of Photoshop.

GL: Interestingly, the short time I worked for Prada covered that big shift in technology. When I started, we were barely using computers or Photoshop and by the time I finished I was shooting pictures digitally – like the dancing pictures from 2001. When I made those it was probably two years before digital was just coming into fashion – I remember doing a lot of research to try and find people with the right kind of equipment. We managed to find one guy who was working in Europe, Emiliano Grassi. He came and handed me a camera with all the stuff connected. It all felt like a miracle, working like that – the previous campaigns were so, so slow. Mainly my fault because we were lighting them in such a laborious way – each shot was taking two or three hours to light and get set up to the point you could get a polaroid. Sometimes more – four or five hours. It was like paint by numbers – this little part of the room needs a highlight there, and this needs something there.

With the second Prada campaign with Amber Valletta, it felt like we had made a big breakthrough with technology purely because the art director David James hired a truck and he brought computers and was able to scan in the polaroids and make a layout and put a logo on it, which was the first time I’d ever had that on set. It really felt like a huge step – it allowed us to really visualise where the campaign was going. Keep in mind this was 24 years ago. But by the last campaign the industry had gone through a complete revolution – everything was digital, even to the point that when I presented the pictures to Miuccia, I presented them on a computer and not on proof sheets.

LS: There are many references behind those Amber pictures. Tell me about them.

GL: I was obviously using a lot of film references to create them. Just pulling elements – a bit of Stanley Kubrick, a bit of Andrei Tarkovsky, just throwing it all together. I hadn’t really thought it through properly, I was just doing it instinctively, and then I remember going to Jenny Saville’s studio and putting the pictures on the floor and she said, “oh, you’re sampling.” It really encapsulated how we were doing it – a bit like how a rap musician would sample tracks. In those days, in fashion, it was a very different system in terms of working with art directors – they didn’t come up with the creative, the photographers did. There was a distinct split between advertising work and fashion work. So if you went to work for, say, a car company, which I did at certain points, that would be done in an ‘advertising manner’ – you’d have the art director and the writer and they would come up with the concept together, sell it to the client, and then once it had all been signed off they would then hire the photographer. It was a finished product; you were just there to bring their ideas to life. Whereas with fashion advertising, the photographer was still very much the creative, so I would go to have a meeting with Miuccia and I would show her video clips or some photos that I had found and tell her my ideas and she would agree to them, or sometimes not.

“When I look at those Prada pictures, they really describe to me in pretty precise detail how much the industry has changed since then” – Glen Luchford

Sometimes, I think about the next step, which is that clients are going to want to put the pictures out as soon as you shoot them, with retouching done on set – that’s coming really soon. It’s inevitable – the demands of social media are instant gratification. It’s funny how different it was back then. What was really difficult, which seems so illogical now, is that it was nearly impossible to find a way to get a film still. For example, the shot of Amber in the boat – there were two references for that. One was from a Tarkovsky movie, Andrei Rublev, and the other was from Time of the Gypsies by Emir Kusturica. When Kusturica did Time of the Gypsies, he was really influenced by Andrei Rublev, so there was this kind of line of influence coming down. I had images from those films in my mind and I wanted to show Miuccia what I was thinking, but it was impossible to find a still of those two pictures. You couldn’t just go on the internet and find it or screengrab it. I tried to find Tarkovsky books, and Kusturica books. If you tried pausing the video on that shot it would just be jumpy, so you couldn’t photograph it off the screen. In the end we found this genius little Japanese machine that would freeze the film and spit out a little postcard-sized image of the exact moment that you wanted. It was really groundbreaking for me. I was able to have all these movie references and print them all out and put them on a storyboard and show people.

LS: Those campaigns are always described as ‘cinematic’ – not all of your work is like that. The images themselves almost look like film stills, but is there a narrative?

GL: I see them as cinematic, yes, absolutely. But I wasn’t creating narratives. I just had films in my head and scenes that had always stuck with me, and I wanted to find a way to recreate them in a fashion context – it was nothing more complex or intellectual than that, it was pretty simplistic actually.

“What’s interesting is that if you look at the photography of that time it was very studio-based and lots of white backgrounds. And, so, I hadn’t seen anything in fashion that was so cinematic” – Glen Luchford

What’s interesting is that if you look at the photography of that time it was very studio-based and lots of white backgrounds. And, so, I hadn’t seen anything in fashion that was so cinematic. That said, if you look back at pornography – magazines like Playboy and American Penthouse from the 1970s – there were a lot of photographers who were lighting in a very cinematic way. The lighting was very good in those pictures. But it wasn’t really being used in fashion. Helmut Newton would create scenarios, I suppose, there was a sort of cinematic appeal to these pictures, but they always had a different quality to them. But I really wanted to go the whole way and light it like a movie – smoke machines, all of that stuff. I remember when I did the first pictures being a little bit scared about them, but I hadn’t really seen something like this before. And when you look at something that’s new it can be quite jarring – I remember being worried about how it would be received. Amber kept looking at the polaroids and looking a bit confused – and I was making her sit for hours and hours on end. Whereas she was used to working with Steven Meisel or Patrick Demarchelier, where you walk in, hair and make-up are done and then you’re shooting – bang bang bang. Then, with me, suddenly your sat on your bony arse in a freezing cold boat in Italy for six hours while we were lighting the picture. She was so patient, but I could tell there was a lot of confusion. Luckily, at one point her boyfriend arrived on set and took a look at the pictures and said he thought they were great, which was really helpful for me – he was the first person coming in from the outside and looking at them with fresh eyes. I was very grateful for that.

And then when the pictures came out, they were very well received, which was good. I definitely felt like we were treading new territory. And then very quickly a lot of images appeared of a similar nature. I didn’t really have a problem with that, but I think people thought that I was taking those pictures – and some of them were really poor rip-offs. I actually remember a photographer saying to me, God you’re working so much. I really wasn’t. I think people thought I was shooting 24 hours a day, seven days a week, just doing all these copies of my own work. But I actually wasn’t allowed to – I was under contract for Prada, so I couldn’t shoot for anyone else.

“I always felt with Miuccia that art was more important to her than fashion” – Glen Luchford

LS: We’ve talked about it as a turning point for the fashion industry and image-making, but also it was a change for your own career – this was probably the first big budget thing you did, right?

GL: I remember that a lot of the people that I came up with started working really quickly and started getting a lot of big campaigns and I didn’t. So, when the Prada campaign came in I was really grateful – I was given a unique situation where I had this amazing patron in Miuccia, who was up for it. I was expecting to go to the first meeting with her and say I really want to do this, and tell her about all the films, and she would say, you are crazy, go into the studio, but she didn’t. She pushed me to do even more. I always felt with Miuccia that art was more important to her than fashion – she never said that, I just presumed it – so you could never be too conceptual with her. The conversations were fantastic. And the more out there you went the more excited she got, so that was a very unique situation.

LS: Tell me more about some of those conversations – it’s interesting to hear you talk about her as a patron, rather than as a ‘client’. I’m used to photographers talking about ‘the client’ in a vaguely frustrated way.

GL: I guess where I’m unconventional, and unlike a lot of my contemporaries, is I don’t need to take pictures every day, every month. I can go a year without taking a picture without feeling any kind of loss whatsoever. I’m not one of those photographers who walks around with a camera in my hands snapping pictures. I get really inspired when I can see a really big picture in my head and then I find a way for someone to allow me to do it. In terms of making that happen, the two really satisfying situations I’ve found myself in have been working with Miuccia at Prada and, recently, working with Alessandro Michele at Gucci. Both of those environments allowed us to really go far.

“For that boat shot of Amber we shut down a part of the river Tiber. Can you imagine shutting the main river in Rome down now?” – Glen Luchford

When I arrived for my first meeting with Miuccia, I really imagined that she wouldn’t be keen on anything, but I found her response to be so invigorating, that when I left to get on the plane home I was literally as high as a kite. I couldn’t believe it was happening to me. Because she’d been so enthralled by the whole thing – so it made me want to go home and do more and be better and come up with more elaborate ideas. And the budgets allowed us to do that – for that boat shot of Amber we shut down a part of the river Tiber. Can you imagine shutting the main river in Rome down now?

We worked with Cinecittà Studios, where they made all the Fellini movies – they still have an amazing art department there. They are really fine technicians, real artisans. So, when I brought in my little screen grab print out of the kid running through the snow maze in The Shining and said I wanted to build this, they said fine. They drew it out on paper, a rough sketch and then they went away and engineered it – they had to figure out the perspective and the length, which they did really well. They spent a week building it, while we were doing the other shots – they brought in like two tonnes of rock salt because that gives you the best snow texture. They were putting in all the little olive branches into the wall individually, creating this maze effect. They were spraying it with this foam that’s used on aeroplanes, because that also gives a good snow texture; every single part of it was so well thought out – and I imagine the cost was crazy expensive, but Prada kept saying yes and signing off on the budget, so for me it was a fantastic, unique moment. At that time there was no other client who would really have given me that opportunity.

PRADA 96-98 by GLEN LUCHFORD is available now, via IDEA.