This article is taken from the Spring/Summer 2021 issue of AnOther Magazine. To celebrate our 20th anniversary, we are making the issue free and available digitally for a limited time only to all our readers wherever you are in the world. Sign up here.

In September last year, a new prime minister was elected in Japan for the first time in almost eight years. The Tokyo Olympics, planned for summer 2020, were postponed: while they are scheduled to take place in July, even now no one is quite sure whether that will happen and, at time of writing, no singing or cheering will be allowed. Japan was among the first countries struck by the global pandemic – a state of emergency was declared there in April 2020. At a profoundly unstable moment in the history of that country – and the world at large – it feels important to listen to the voice of one of its great creators, a woman who has followed her own, highly unconventional path, without compromise. And if Japan is compelled to listen to Rei Kawakubo, so too is fashion. Her business, founded in 1969, is 52 years old, and there are few, if any, names that are as universally respected – even revered. In 2017, she became only the second living designer to be honoured with a retrospective at the Metropolitan Museum of Art Costume Institute in New York, following Yves Saint Laurent in 1983. Both names have fundamentally altered the way we look at fashion: Saint Laurent revolutionising women’s wardrobes, Kawakubo reconfiguring our perceptions of our own bodies in clothing, notions of status and, again, the way we choose to dress. So much do we take that for granted that we may no longer even be aware that our boiled-wool sweaters, our oversized dresses, our unlined, deconstructed jackets and even our wearing of head-to-toe black, other than for periods of mourning, started life here. The collective fashion memory is a short-term one but it is testimony to Kawakubo’s courage as a designer that, for many years, while she preached to a small audience (the converted), she ruffled the feathers of the establishment to the point where people left her shows confused and even disturbed. Other commentators simply ignored them: the shock of the new indeed.

The first time I met Kawakubo was at the Comme des Garçons showroom in Paris’s Place Vendôme in October 1996, a few days after she had shown one of her most famous – and controversial – collections. Featuring padded lozenges of fabric placed everywhere from the shoulder blades to the buttocks and hips, it was explained, in a statement from the label at the time, as Body Meets Dress, Dress Meets Body and has been ever since. For years the collection was described in more mainstream circles, and none too poetically, as ‘lumps and bumps’. And – inevitably – more than a few wondered: did their bums look big in this? Here is Amy Spindler, then fashion critic of the New York Times reviewing the show in that paper: “At one point, as a model emerged, her shoulders stuffed, a photographer yelled out ‘Quasimodo’ into the deathly silent presentation, with no music and certainly no chatting.” While there is often still no music or chatting at Comme des Garçons, no one would be as gratuitously ill-mannered today. It is all too easy to forget, though, how hard Kawakubo has fought to express her point of view. When I, meanwhile, asked the designer in person what the thinking behind this collection might be – and I have since repeated the anecdote many times – she picked up a pencil, drew a circle on a scrap of white paper and walked away. Perfect. I have been lucky enough to communicate with Kawakubo on several occasions over the two decades since then. While she is not shy – or certainly reclusive – she does insist that the clothes she designs speak for themselves. Or as she herself once said: “In normal everyday circumstances, of course I’m not reclusive, but this fascination with every nosy detail is so astonishing. It would be much better to know someone through that person’s work. With a singer, the best way is to listen to his song. For me, the best way to know me is to look at my clothing.”

In the autumn of last year, however, so affected was Kawakubo by the global crisis, she felt driven to vocalise her thoughts maybe more than ever before. In October, immediately following the showing of her Comme des Garçons collection in Tokyo at the company’s headquarters – it is the first time she has staged the show for her main line in her native country since the early eighties – she agreed to be filmed for the Japanese television programme News23. This, as far as we know, while clearly not intended as Kawakubo’s answer to Keeping Up with the Kardashians, is unprecedented. Previously, her voice has been recorded in interview – notably in a little-known and remarkable four-part documentary from 1998 called Un-Dressed: Fashion in the Twentieth Century, written and conceived by Sally Brampton, in which she talks over images of clouds moving across a blue sky – but she rarely agrees to appear in person. The conversation for the monograph that accompanied the aforementioned Costume Institute show begins: “I hate interviews.” (If Kawakubo is a woman of few words, no one would ever accuse her of mincing them.) Now though, speaking through a mask, her delicate features belying her resolve: “I wanted people to see how important the power of creation is at such a difficult time like this.” The term she used to describe the collection in question, meanwhile, was fukyo-waon. It translates as dissonance. Kawakubo continues to keep any discussion of inspiration to a minimum, preferring people to make up their minds for themselves. But, from her hands, and out of dissonance, for more than half a century, unparalleled creativity has come.

If the prevailing mood in fashion decrees that eased collections (lovely, maybe, but aimed squarely at the endlessly expanding market described as athleisurewear) are the order of the day – for the most obvious reasons – Kawakubo was never likely to follow that route. Instead, hers was a courageously iconoclastic collection and one that, despite any apparent discord, resulted in something extraordinary, as the designer herself says. Kawakubo was also intent on “disrupting the spirit of couture” – given that this is the mother of all fashion disruptors, that was something of an understatement. In fact, she turned that spirit on its head. Kawakubo speaks of anger, of difficulty, of fear, but her clothes are transportive, enchanting. Hugely generous in their depth of content, craft, ideas and often extreme beauty, they are a sight for Zoomed-out eyes.

In a small space flooded with crimson light (a bordello? Hell?) and to an audience smaller even than that in Paris – Kawakubo famously shows to no more than a few hundred guests – out came the voluminous, abstracted silhouettes that Comme des Garçons is known for. A whisper of an 18th-century pannier or a bustle, a fairy-tale cloak, over-blown dresses and skirts decorated with lace, knots and bows: festooned. But where, in the haute couture atelier, these would be cut in silks and satins, in Kawakubo’s hands they are padded, unapologetically acrylic and in places more rope than ribbon-like. At least some of these designs were wrapped in plastic. Imagine a vacuum-packed, punked- and popped-up Madame de Pompadour for this messed-up modern age.

Mickey Mouse was among the stars of the show this time, perhaps significant because Kawakubo went to school while the American army still occupied Japan. In his 1990 monograph on Comme des Garçons, the first extensive English-language text on the label, the writer and curator Deyan Sudjic observes: “By the time [Kawakubo] graduated, the country had decisively emerged from the ranks of the developing world. The ferment of those years provided unique opportunities for the members of a generation that was ready to make the most of them. They enjoyed the fruits of an economic success story which enabled Japan to look at the outside world in objective terms, to make its own creative contribution and, in the process, to assert its own identity as a mature, modern state.” Among the names that went on to do just that are the architects Tadao Ando and Arata Isozaki and Tokyo-based fashion designers Issey Miyake, Yohji Yamamoto and Rei Kawakubo.

Like Coca-Cola, Disney’s Mickey Mouse is among the most instantly recognisable symbols of American culture. In the Spring/Summer 2021 collection, the clothes were teamed with snub-toed platform-soled shoes, not dissimilar to those he wears, and he appears as prints, repeated and overlapping to the point of abstraction, scribbled across surfaces like graffiti. Kawakubo has used this reference – and the childlike innocence it expresses – before. For her Autumn/Winter 2007 women’s collection, models wore candyfloss pink and parma violet dresses and Mickey Mouse ears, their bodies hugged by padded gloves reminiscent of Mickey’s embedded in the clothes. When asked about that particular collection, which appeared to concern itself with a young woman’s rites of passage, Kawakubo said simply that it was about “curiosity”. Kawakubo’s own curiosity is inspiring. She continues to ask questions – endlessly interrogating herself, questioning the world. Such restlessness drives her. Alongside the Disney character in last October’s show was Bearbrick, a collectible toy designed and produced by the Japanese company MediCom Toy Incorporated and ubiquitous in Japan, the Mickey of Tokyo. For Spring/Summer 2018, Kawakubo juxtaposed that other great Japanese toy – Hello Kitty – and blonde, blue-eyed manga princesses with digital prints of works by the 16th-century Italian artist Giuseppe Arcimboldo, painter of unsettling portraits made out of vegetables and fruit. Dissonance there too, then, not to mention a deep-rooted irreverence that decrees high culture and low culture are equally important and that Kawakubo takes such apparently separate worlds and makes the most beautiful sense of them.

Of course, fashion has changed immeasurably since Kawakubo started out, for better and for worse, but this great designer remains unswervingly committed to her craft. From small beginnings, she today heads up a fashion empire that includes not only many Comme des Garçons lines but the labels of Junya Watanabe and Noir Kei Ninomiya. In recent years she has been more willing to speak to a broader audience, not least with that 2017 retrospective. If, as she continues to argue, anger motivates her, so too does passion. And that passion to create and to communicate via creation has rarely felt as meaningful as it does now.

AnOther Magazine: I understand you worked non-stop throughout lockdown. Is that right?

Rei Kawakubo: I am afraid I won’t be able to create any more unless I keep going. Once I stop, that would be it. It is that fear that keeps me moving forward.

AM: While many people are showing collections digitally, you are filming live presentations, if necessarily shown to a small audience. What is the thinking behind that?

RK: I always want people to look at the clothes themselves and for the audience to see clothes on real people. Clothes deliver our messages better when they are worn. It is difficult to explain in words, but once the clothes are put on people, all their elements come into harmony and start showing their strength. That is because people and clothes step closer to each other, I think.

AM: So there are things digital media just can’t convey?

RK: Digital media would not be able to convey half the things I want to express. At a live show, you are able to feel things – the power of the clothes and the effort that has gone into making them, the atmosphere and the presence of people wearing them in front of you. Some people may believe otherwise, but for me to express something digitally would be a different thing – a deviation.

AM: This is the first time you have shown the Comme des Garçons main line in Tokyo for decades. How did you find that? How was it different and did you feel there was anything positive about it?

RK: To travel to Paris is physically very difficult right now. For business, however, we must do a show one way or another, and I feel strongly that I must constantly keep putting out new things too. So we must cope with this situation somehow. In Paris, people come from all over the world to see our show and they do not always say good things. They make negative comments sometimes. Also, in Paris, there is invisible competition with other designers. Tokyo certainly isn’t that kind of place, but all our staff work hard and the clothes we make and the process of making them are exactly the same as when we show in Paris. The only difference is that while, for Paris, you put the clothes on the aeroplane, in Tokyo you carry them up to the seventh floor.

AM: You have a big company. How does that responsibility affect you?

RK: Closing the stores for about a month last year caused a lot of damage to our business. It was not something I could solve no matter how much I struggled thinking about it. There were no customers from overseas either. There were things I could do during the 2008 financial crisis but this time everything was closed, including the factories. The question is how we recover from the loss now.

“The human brain always looks for harmony and logic. When harmony is denied, where there is no logic, when there is dissonance ... a powerful moment is created which leads you to feel an inner turmoil and a tension ... that can lead to finding positive change and progress” – Rei Kawakubo, October 2020

AM: What are the particular difficulties that the pandemic has caused you personally and how would you say that has affected you creatively?

RK: Like I said, what made this crisis different is that there was nothing I could do about it. Before, there were a few things I could do to hold out. Today, there are many agendas to tackle in order to solve the problem. Our work is to make clothes, we have the next collections, exhibitions coming up, and we cannot stop that. Telecommunications are suggested as an alternative way forward but there are things that cannot be done that way. Manufacturing in particular. Not everything can be done with computers. There are things it is only possible to make by touching and feeling and using all the five senses. Human beings are creatures with sensibilities. I value the things people make with their hearts more than digitally fabricated things. There are obstacles and uncertainties under these circumstances, but as long as we can make things, there will always be a future.

AM: Your new collection features plastic wrap, Mickey Mouse and Bearbrick, as well as perhaps more familiar oversized and sculptural black designs. Can we talk about that a little?

RK: It is about dissonance, things that don’t match very well, but that feel good. I’m interested in dissonance because I believe good things come out of it, something curious, unexpected, something that feels new and that could lead us to the next step. In classical music, too, early works composed with dissonance were often heavily criticised but that invention is still valid today. Some people may find it repulsive when things of a contrasting nature crash into each other, but there is a chance we may find something different there. If things are neatly put together and positioned in a regular way all the time, there won’t be progress.

AM: And why did that interest you now?

RK: As the pandemic is interfering with our lives, the spirit of moving forward is also fading. And that very thing, I am afraid, may become an excuse for not challenging ourselves, reaching higher goals and making new creations – taking risks to move forward. The economy is down and life is hard but we must bear the hardship and look forward. There is no easy solution. I believe we should never stop.

AM: Do you feel that people are maybe less passionate now than they once were? And how has that affected fashion?

RK: Maybe not to feel and think is easier. People maybe don’t understand what there is to gain by struggling hard. They have less and less desire to be themselves and would rather be comfortable and blend in, wear safe clothes.

AM You neither wear nor design safe clothes. Is your drive to design intended to make the world a better place – or a more interesting place, certainly?

RK: I feel anxious I may lose that power any time soon. But for me, to live is to work, to create. Nothing else. I can only do what I can. I direct my anger to creation. I am happy if I can make something that inspires some people. If you want to make something you must make an effort and never stop. I believe that is true for other kinds of work too. Comme des Garçons owes what it is now to those who have dedicated their lives to manufacturing, at times at a cost to their personal lives. It is their work and efforts that form the foundation upon which we have built what we have today. We must carry on to advance further. What I am afraid of is that if this situation continues, people might start to feel like giving up, they may stop expressing themselves and vocalising their presence. In that case, a mood for being the same as everybody else would prevail and then the world becomes infertile.

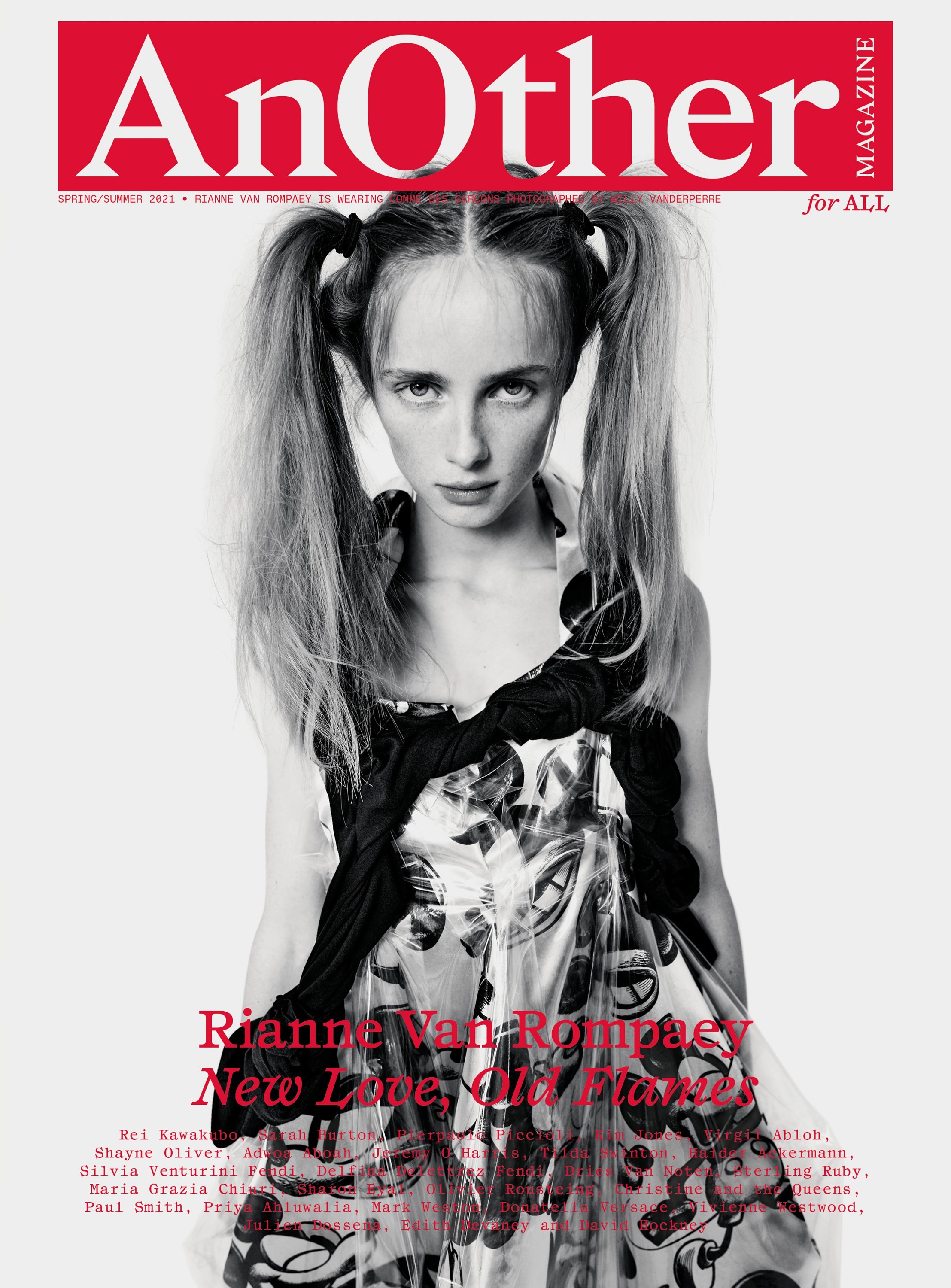

Hair: Anthony Turner at Streeters. Make-up: Kathinka Gernant at Unspoken. Model: Rianne Van Rompaey at Viva London. Casting: DM Casting. Manicure: Lynn Meyer. Lighting technician: Romain Dubus. Digital operator: Henri Coutant. Photographic assistant: Samir Dari. Styling assistants: Louise Pollet, Jasmien Van Loo and Niccolo Torelli. Hair assistant: Claire Grech. Producer to Willy Vanderperre: Lieze Rubbrecht. Production: Mindbox. Producer: Isabelle Verreyke. Project manager: Lise Luyckx. Post-production: Triplelutz Paris

This article originally featured in the Spring/Summer 2021 issue of AnOther Magazine which will be on sale from 8 April, 2021. Pre-order a copy here and sign up for free access to the issue here..