Several years ago, the Irish designer Richard Malone presented a collection in what he called “supermarket shades”: Tesco blue, Sainsbury’s orange, Co-op green. He said he was drawn to them because they reminded him of the bustling markets in and around his hometown of Wexford, on Ireland’s east coast, and the women who frequented them, with shopping bags on their arms. If the colours suggested mundanity, in his hands, they were anything but – they were used vividly, swept up into dresses which twisted around the body or split away into streamers at the hem.

Memories such as these are the bedrock of Malone’s work, which first caught attention with a prize-winning final collection at London’s Central Saint Martins in 2014, before the designer was scouted by Lulu Kennedy’s Fashion East incubator a year or so later. Though primarily based in London, Ireland looms large over his work: he is a deep thinker, and each of his collections in one way or another can be traced back to a childhood and teenage years spent between countryside and coastline, in the small rural community in which he grew up. He has a unique ability to transform these unassuming memories into thoughtful, artistically-minded womenswear, which always comes back to what he calls a “human energy” – a communion of both the wearer and the hands which made it. “I don’t think there is much to clothes until people are in them,” he previously told AnOther.

Which is why, when we talk about his highest-profile collaboration to date – a limited-edition collection of handbags and accessories with Mulberry as part of its 50th anniversary celebrations – he talks not of those rarefied accessories locked up behind glass on Bond Street, but his father’s tool bag, worn around the waist on the building sites he worked on while Malone was growing up. Designing a handbag, he realised, was able to be approached with the same pragmatism as his collections – yes, there is a desire to create something memorable and beautiful, but all that is pointless if the item in question cannot be worn as part of somebody’s everyday life. That would be a waste. And Malone hates waste.

So he thought about his father’s toolbelt, the bag his mother used to carry her belongings to work, luggage and travel bags – accessories with purpose. “I think when you are from a town that is very working class, you realise bags have a certain status,” he explains. “And also that they were there to serve a function.”

In some ways this humble approach appears at odds with Mulberry. For although the brand was started when its founder began making accessories at his kitchen table using scraps of leather, it has an innate sense of luxury – much down to its link in the popular imagination with celebrity culture, its Bayswater and Alexa handbags part of the definitive iconography of 00s fashion. But Malone – who says he is often approached for, and has turned down, such collaborations in the past – was struck by how many values he shared with the brand, not least with the simple discovery that customers were returning 30 years later to Mulberry to get their bags repaired (the brand also runs a service called Mulberry Exchange, whereby it buys back older models in return for an agreed amount off a new purchase). It spoke not only to that sense of functionality – clearly these bags served their purpose, having been in use for so long – but also to Malone’s belief that such marks of quality are essential for a business to call itself sustainable, a value at the forefront of his label.

He likes Mulberry’s understated approach and compares it to the way that he has built his own business, which has eschewed the typical model of making money from selling wholesale to retailers, by instead selling directly to the consumer. His clients are mainly women from the creative fields of art, architecture and film, served in private appointments where needs are discussed and garments fitted directly to the body. The ambition is that the piece will be worn for life, reflecting Mulberry’s Made to Last ethos.

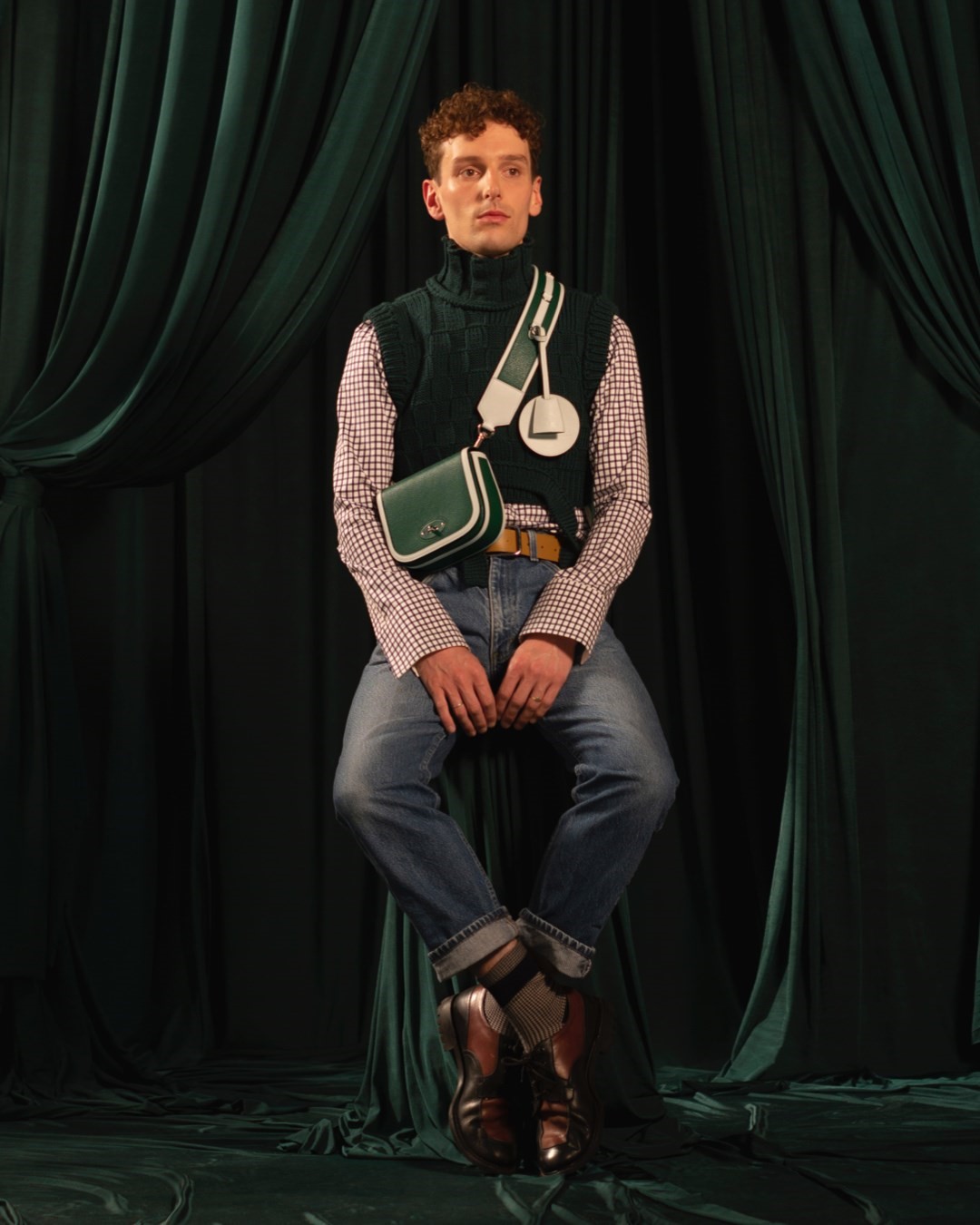

The collection itself saw Malone playfully de- and reconstruct two of Mulberry’s most memorable designs: the classic Bayswater and the smaller, more ladylike Darley bag. Pockets, piping, and serial numbers were moved from the inside out. New shapes were made – a version of the Bayswater comes with a triangular end or a cylindrical one, the latter like a barrel (one inspiration was holdalls, and mid-century luggage). Other pieces in the collection are shrunken, made to be worn across the body like Malone would on a night out, “slipped under his arm”. Fabrics are sustainably minded; Mulberry’s signature Scotchgrain material, a hallmark since the brand’s founding, is remade here from inedible cereal waste and makes up the majority of the collection.

The colours themselves – red, green, blue, accents of white – are utilised for their immediacy, Malone likening them to the bottles of poster paint you have in childhood (Malone is adamant that he will never use black; “I can’t even write in black pen,” he says, “I struggle to see it, it doesn’t jump off the page to me”). They also draw him back to his beloved grandmother Nellie, who worked as a seamstress. Much of his new collection, which was presented at the V&A this weekend as a part of London Fashion Week – alongside accessories from the Mulberry collaboration – drew inspiration from the small acts of craft Malone would watch her do growing up. Namely, the creation of the colourful rosettes awarded at horse shows or Gaelic football tournaments. “It’s something that would be entirely overlooked because it’s not gold, it’s not silver, or it’s not ceramic. They are made out of synthetic fabric or leftover fabric, but there’s so much energy in it,” he says. “The fact that the show’s gonna be at the V&A, that contrast means something to me.”

It all weaves into an approach to sustainability that goes beyond, as he puts bluntly, “patching together old fabric”. Instead, it’s about that “human energy” on which craft relies – the age-old traditions of the garment industry in both the UK and Ireland which are slowly dying out. “When you talk about sustainability you have to talk about craft and scale,” he says. “Just because something’s sustainable it doesn’t make it interesting, or good. You’re eliminating the voices of people who are experts in flou, or draping, or tailoring, or putting in sleeves. I want to talk about those things – they are real skills being lost. What is the solution?”

These were the sorts of questions Malone put to Mulberry when the brand first approached him for the collaboration. He asked about its ethics, its supply chain, and discovered they had many of the same suppliers. And that its factories taught traditional craft and leatherwork through an ongoing number of apprenticeships. Meanwhile, to mark its 50th anniversary year, Mulberry has launched the Made to Last Manifesto, laying out an ambitious commitment to transform the business to a regenerative and circular model, encompassing the entire supply chain, from field to wardrobe by 2030. Within it, there were outlines of a supply chain it termed “hyper-local, hyper-transparent,” and blueprints for further expanding their program of regenerative farming. “I’ve always thought of myself as being very lucky to grow up where I did,” Malone says. “Part of the reason as to why I’m so passionate about sustainability is because we grew up near farms, and we understand seasonality.”

All this said, Malone is aware that perhaps more than any accessory – excepting perhaps shoes – the choice to purchase a handbag comes down to a more fetishistic desire to adorn the body with something shiny and new. I ask him who he imagines wearing the handbag, and he admits he doesn’t quite know – he says he avoids the “typologies” of luxury brands, the marketing inventions that dictate the people who wear their clothes. “It’s always like, a self-made creative, artistic, very wealthy woman, who has all the time to shop,” he says. “Which is not a real person.” What he does know is that when, a month or so ago, he gathered a group of his closest collaborators to photograph them for the accompanying campaign – the photographer Ronan McKenzie, the artist Thomas Garnon, the jeweller Rosh Mahtani of Alighieri, Lulu Kennedy of Fashion East, and his longtime stylist and AnOther Magazine senior fashion editor-at-large Nell Kalonji among them – they were quick to choose a handbag from the collection to wear for the portrait.

“Theirs are the opinions I really value, and everyone just picked their own; the one they would actually carry, and they were excited,” Malone says. “That was a sign to me that we’ve done something good. It felt real.”

The capsule consists of a Bayswater, Mini Bayswater, Triangle Bayswater, Barrel Bag and Small Darley. These are accompanied by accessories including a Coin Pouch and Key Fob. The Mulberry x Richard Malone collection is available to purchase now at Mulberry.com and in stores globally.

Other iterations of the Mulberry Editions series include collections by Malone’s London-based contemporaries Priya Ahluwalia (launched this past June) and Nicholas Daley (coming November).