It’s impossible to be in two places at once – unless, of course, you’re Prada. The complexity of staging a fashion show at the best of times cannot be overestimated: at the tail-end of the pandemic, logistical headaches are compounded with genuine concerns for safety and government restrictions on distancing and capacity. Plus this Spring/Summer 2022 show was, of course, the first in-person debut of the creative partnership between Miuccia Prada and Raf Simons, some 18 months and four shows after it was first announced.

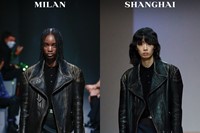

Yet Prada decided to add another level – an idea so overarchingly simple as to hint at its own difficulty. Why not stage the same show in two places, at the same time? It was held in both the vast Deposito of the Fondazione Prada, and the Bund 1 space in Shanghai. Milan’s show space was grey, Shanghai’s a blushed peach; Milan kicked off just after 3pm, Shanghai was a 9pm evening affair. And each decor, created by Rem Koolhaas’ AMO, was punctuated with video screens displaying the progress of the sister show on the other side of the world. “It’s no longer about a small world – in fashion, or elsewhere. It’s about a wider connection,” Simons said. “Our engagement with technology, the use of technology to mediate between humanity, was the inspiration for the first show of Raf and I,” said Miuccia Prada. “This show reflects that idea, also. After all that has happened, how can you just go back?”

Indeed. Fashion shows are always a vision of the future – this was for next spring, remember. Yet so many look backwards – not least now, with a desperate, nostalgic yearning to wipe out the experiences of the past two years. I keep thinking of Dior’s New Look, a great backwards-looking glob of nostalgia porn that debuted less than two years after the end of the second world war and, in glancing back to the romantic fashions of the 19th and early 20th century, attempted to erase the memories of hardship, strictures, fabric shortages. An illusion of plenty, to forget loss. The same instinct is evident this season in Milan – the phrase most often used, about the in-person shows and appointments and a busy schedule, is “back to normal.” “I strongly disagree with the idea of a return to ‘normal’,” says Miuccia Prada. “We must draw lessons from this moment.”

And Prada had. It had learned, on the one hand, the importance of physical community – of coming together to celebrate. That’s something everyone is into. But Prada and Simons had also learned about the vital role of technology to connect people – one only learned through necessity, but one which could, potentially, continue to transform the way we communicate. It felt transformative here. The futurism of this show, the possibilities it demonstrated, was arresting. As you watched the show unfold, models on those vast screens walked in exact synchronicity with their counterparts in the room. The clothes were the same, everything else different. It would have been easy for it to distract or detract, but instead in enhanced, focussing attention on the only point of similarity – the clothes. If Prada wanted to, they could have held this show in another few places – why not a pistachio-green Prada set in South America? A slate Prada blue terrain in Africa? They could have all flashed up on those screens too, playing between reality and virtual. Just a thought.

But back to the clothes – they were also focussed, an exercise in reduction and simplicity, ideas Miuccia Prada and Raf Simons have been exploring insistently and consistently ever since they began to work together. This time, they took on history. “Trains, corsets, evening gowns. These things that are historically beautiful – they are interesting, but we want to disturb them,” Simons said. “We thought of words like elegant – but this feels so old-fashioned,” agreed Miuccia Prada. “Really, it’s about a language of seduction that always leads back to the body. Using these ideas, these references to historical pieces, this collection is an investigation of what they mean today, what seduction means. Why are these ideas still important, after hundreds of years?”

Here, seduction was reduced to its bare bones – bones being one thing that punctuated the collection. The exposed stays of traditional corsets served to emphasise waists – they didn’t cinch, rather pulling the clothing away from the body as opposed to crushing it underneath, on dresses that were left open at the back, revealing tantalising slivers of skin. The same with the briefest of mini skirts, where the trains of grand evening dresses were reduced to simple gestures of fabric in back, like the trailing ribbons of bows quickly unfastened. The clothes were transformed in motion, and the body was vital to their construction – knitwear had unerring to pull it close against the breasts, as if an impression of the body was embedded into the fabric itself. And both of those are automatic, entirely natural reactions to the world today: after so long away from one another, so long still, the urge to feel another human body is palpable, so too the urge to move, to be free. This collection was, of course, intellectually rigorous – Prada and Simons are two of the great fashion thinkers of our time. But it was also direct, spontaneous. It felt right.