This article is taken from the Autumn/Winter 2021 issue of AnOther Magazine.

“Fear.” The designer Demna Gvasalia is talking about the emotions, namely his own, triggered by the daunting task of presenting his first couture collection. It’s May 2021 – the show is in July. “This is a little bit like a therapy session,” he’ll later add, laughing. His feelings are heightened because this couture collection is not just for himself, but for the august, austere house of Balenciaga, where couture – arguably – was raised from applied to pure art at the hands of its founder, Cristóbal Balenciaga, a legend in his own lifetime, deified since. He retired in 1968 and died in 1972. Couture bearing the label Balenciaga has never been designed by anyone other than him – until now. “This is the house where couture for me is kind of like innate, the essence,” Gvasalia says. “I felt it was my obligation.” But still, there’s fear. “Fear of not being enough. Fear of having to fill these very big shoes, left by ‘the master of us all’.” He isn’t laughing. “It’s not just a legacy – it’s Cristóbal Balenciaga’s legacy.”

Gvasalia has every right to be afraid, given that the history and prestige of the house of Balenciaga is, possibly, unparalleled in modern fashion. Others come close, granted. Christian Dior ensured his name’s immortality by resuscitating Paris haute couture after the strictures of the second world war, by saving women from nature and creating a fashion moment with his 1947 debut that outmoded all before it. Gabrielle Chanel emancipated women not once but twice, first in the 20th century’s teenage years, and then again after her comeback in 1954, inventing a uniform of modernity, eschewing fickle fashion in favour of eternal style. Yves Saint Laurent, Dior’s dauphin, rebelled in the 1960s and then refined, dedicating himself to the perfection of his craft. They are all couture greats, names whose work changed fashion. Yet the sombre Spaniard Cristóbal Balenciaga is feted as the greatest of all. Even those contemporaries – and others – openly acknowledged it. It was Dior who first called him “the master of us all”, comparing the couture to an orchestra composed and conducted by Balenciaga. “Balenciaga alone is a couturier,” said Chanel – who rarely praised anyone except herself. “The others are draughtsmen or copyists.” Madeleine Vionnet called him “un vrai”; Balenciaga’s friend and devoted disciple Hubert de Givenchy declared he was the greatest single influence on his career.

Almost half a century after his death, Balenciaga is still revered as the most significant figure of 20th-century haute couture, a defining architect of fashion as we experience it today. Balenciaga founded his couture house in San Sebastián, Spain, in 1917 – it was named Eisa, a diminutive of his mother’s surname Eizaguirre – expanded to Madrid and Barcelona, and in 1937 opened as Balenciaga in Paris, at 10 avenue George V. When that address – and the other branches – closed in 1968, the New York Times ran the news under the headline “Nothing Left to Achieve, Balenciaga Calls It a Day”. Nothing left to achieve because, in the 51 years in between, Balenciaga had reinvented how people dressed. His clothes were paradoxically formal and fluid, could appear heavy and architectural yet were magically weightless, “like a sea swell”, wrote Pauline de Rothschild, who, like pretty much every other woman of note, wore Balenciaga.

“One never knew what one was going to see at a Balenciaga opening,” wrote Diana Vreeland, breathlessly, in her 1984 memoirs. “One fainted. It was possible to blow up and die.” Balenciaga’s most passionate client was Mona von Bismarck, who featured in Cole Porter lyrics and Vogue photo spreads, and who ordered everything, including cinnamon-coloured gardening clothes, from the couture house. She was immortalised by Cecil Beaton in Balenciaga’s trapeze-line draped-back satin evening dresses, shot from behind to show the collar elegantly dipping at the nape. When the house closed she retired to her room for three days, to mourn.

In May, when Gvasalia and I meet at the Balenciaga archives, held in a vast warehouse on the outskirts of northern Paris, he has already been preparing for his couture debut for 18 months. Balenciaga had originally planned to present the line in July 2020 but was stymied by the Covid-19 pandemic and lockdowns that achieved what two world wars and the Nazi occupation could never do in halting the Paris haute couture shows for a year. With hindsight, however, Gvasalia says he’s been thinking about couture for six years – since he first began designing for the house in 2015. Surprising, because you wouldn’t immediately connect Gvasalia’s designs to couture, for many reasons. They are ready-to-wear obviously, their slick surfaces and sharp silhouettes revelling in an industrial quality inherent to their manufacture, while aesthetically and ideologically they sit as far away from the fluffy extravagance that characterises most modern haute couture, focused as it is on event dressing. When Cristóbal Balenciaga closed the fashion house in 1968 he reportedly told a distraught client, “Why do you want me to go on? There is no one left to dress.” Ready-to-wear, he recognised, was the future, but he had no interest in it.

“This is the house where couture for me is kind of like innate, the essence. I felt it was my obligation” – Demna Gvasalia

People store priceless fine art in the out-of-town repository where Balenciaga keeps its archive, a space segmented into aircraft-hangar-sized spaces crammed with stuff whose collective worth is equivalent to the GDP of entire nations. The Balenciaga archive houses some unusual things alongside clothes – the remnants of Cristóbal Balenciaga’s personal library and art collection, the furniture from his homes piled on shelves, even an elevator padded in cordovan leather that once ferried clients in his couture house. It has examples of ready-to-wear clothes by Cristóbal Balenciaga’s successors – lesser-knowns such as Josephus Thimister, who designed Balenciaga from 1992 to 1997, and the famous 21st-century trio of Nicolas Ghesquière, Alexander Wang and Gvasalia. There are also pieces actually made by Cristóbal’s own hands – holy stuff. Each collection, Balenciaga purportedly sewed one black dress entirely – he learnt the craft directly from his mother, a seamstress, and was venerated for his faultless technical ability alongside his creativity. Balenciaga would frequently make clothes for himself to wear, including such oddly un-Balenciaga garments as a ski anorak, sewn together on the eve of his departure for holiday. One 1960s collection featured a coat with sleeves that were based on Balenciaga’s own raincoat – Women’s Wear Daily, which often snubbed its nose at Balenciaga’s hauteur and the reverence with which he was held in the fashion industry, dubbed it a “Balenciagaberry”. Balenciaga wouldn’t sketch, rather he worked directly on the fabric of toiles, manipulating material in three dimensions until they achieved the effects he craved – a methodology echoed in Gvasalia’s own, where he chops up existing garments to shift forms on the body.

Anoraks, raincoats, brand mash-ups, high and low – there’s a whole bunch of unanticipated parallels you can find there between Gvasalia and Balenciaga. The most enduring connection between the two, however, is their quest for modernity – although the meaning of modernity in 1960s Parisian high society and circa 2021 is, of course, fundamentally different. Back then, it revolved around haute couture – today, women wear tracksuits rather than tweed suits, sportswear for everyday that can perhaps be traced back to Balenciaga’s revolutionary semi-fitted suits of 1951, which traced an eased line that foreshadowed not just the silhouette of the 1960s, but a whole modern idea of comfort in dress. “Parkas, denim jackets, five-pocket jeans,” says Gvasalia. He’s talking not about ready-to-wear here, but his couture. He’s talking about how he can make couture feel modern, for him.

“When I started, there were a lot of Cristóbal dress references because that is the base,” Gvasalia says. “I need to bring that elegance into this time. But I also want clients who don’t walk through a palazzo in Venice, in the robe manteau of Mona von Bismarck.” He laughs. “It’s somebody who, I don’t know, travels in haute couture. Because there are people who do that – I don’t know them, but I hope to know them.” Gvasalia has always been superb at unpicking his thought processes: he makes for an incredibly engaging interview. Here, next to Cristóbal Balenciaga’s old furniture, he is giving an ad hoc synopsis of his new take on couture. “It’s a trench coat. It’s a tailored suit. I will even have a couture T-shirt. I need to extend it. For couture to be modern, it has to be a wardrobe.” He pauses. “We cannot get locked into the ballroom.”

When you enter the Balenciaga archive, you are given a small oxygen monitor: the airflow is controlled and the climate, generally, is maintained at -7.8C (18F), a temperature so low fire cannot ignite. Off to the side is a rail of new (old) acquisitions from auction houses: a sculpted sheath dress in searing yellow duchesse satin from 1962, a black cashmere evening coat from 1951. In the back, there are several racks from which recent Balenciaga collections hang. Gvasalia won’t look at those, he tells me. He is wearing a long black coat, like the inverse of the traditional white couture worker’s smock, his hair closely cropped. He’s looking at an elaborately embellished bodice, contained in a grey cardboard archive box – the type known, in the trade, as “coffins”, because dead clothes sleep inside them. The bodice, swollen with tissue padding as if still inhabited by a living body, is pale silvery blue silk jacquard, a base for embroideries of strewn flowers in glass beads with crystal droplets. It’s a little raggedy, threads plucked and hanging loose, as if it’s been bashed about, with uncharacteristic disrespect, for half a century or so. Only it hasn’t: the piece is new, the top of an evening dress from his forthcoming couture collection. “This we have been working on, I think, for two months,” Gvasalia says. Its decoration is executed by the young French embroidery atelier Jean-Pierre Ollier and painstakingly sewn to seem, for want of a better term, a bit fucked up. Other pieces from the collection are too, like a sack-back evening coat in a poison green silk taffeta that is permanently crumpled, as though it slid off its hanger to the bottom of a wardrobe long ago and was left to moulder.

“I like the idea that couture is an effort to come as close as possible to perfection,” Gvasalia says, incongruously, staring down at the plucked surface. “I think Cristóbal’s idea of couture was that. He was a perfectionist.” Understatement of the century: Balenciaga was an absolute obsessive, “a haunted man” according to his parish priest and confessor Father Robert Pieplu, “haunted by a great plan, a vision of the world”. That vision accepted nothing short of perfection. Sleeves were a fixation, his couture house resounding with anguished cries of “la manga” as Balenciaga ripped his garments apart with his own hands, remaking again and again. He would not permit anyone else to pin his designs in his presence and, when he was asked to design the uniforms for Air France in 1968, he wanted to fit each of the 6,000 outfits himself. Conversely, Gvasalia has never been interested in achieving perfection. “Perfection doesn’t really exist. I don’t really believe in that,” he says. “I feel I always look for beauty in places that are not conventionally understood as that.” Gvasalia’s clothes, first for the label Vetements (which he co-founded in 2014 and left in 2019) and latterly for Balenciaga, have made a feature of their unusual fabric treatments and odd proportions – inbuilt creasing, bleaching, puckering and mismatched prints, coats tugged across the body and deliberately misbuttoned, shoulders cut to slide forwards, to almost round the back.

Back in 2016, when I spoke with Gvasalia for a profile for this magazine around his first ready-to-wear show, he recounted a story of Cristóbal Balenciaga draping fabric on a client, “of how this woman was transformed. How he changed the posture, the attitude,” Gvasalia said. “For me, that was the most important part. That was, for me, the source of inspiration. How do we do that today? How do we transform the attitude?” Gvasalia, though, is more likely to create a hunch than hide it: a Schiaparelli-pink satin faille coat in this couture collection looks a bit like it has a sofa cushion stuffed between the shoulder blades, an extension of a collar line Gvasalia drew from the stand-away collars of Balenciaga’s 1960s suits and translated into his clothes right from the start. His Oxford stripe shirts and denim jackets dip delicately at the nape, a nod to Mona von Bismarck.

“Perfection doesn’t really exist. I don’t really believe in that” – Demna Gvasalia

Attitude is all-important to Gvasalia. Attitude can mean both a physical posture – a gesture, a stance – and a mindset. It can also denote truculent behaviour. All three are evident in his approach. If today Gvasalia is in a reverential mood, it hasn’t always been the case. He has affixed Balenciaga’s name to tracksuits and trainers, to T-shirts with reconfigurations of the election merchandise of 2016 Democratic presidential nominee Bernie Sanders. Cristóbal Balenciaga was, by contrast, avowedly apolitical: he fled the Spanish Civil War in 1937, yet the final dress he created was a wedding dress for General Franco’s granddaughter Carmen Martínez-Bordiú in 1972. When Balenciaga decided to close his couture house, it was in the midst of sociopolitical upheaval – news breaking of the May 1968 Paris student protests, the world transforming before his eyes. However, Gvasalia reacts to those streets, translating the attitude of its founder into unexpected clothes, including hooded sweatshirts, leather jackets and jeans. Born and brought up poor, Balenciaga was a snob: he declared his house must dress only thoroughbreds and quoted Salvador Dalí – another Spaniard – when he stated, “A distinguished lady always has a disagreeable air.” So you may think he wouldn’t like sweatshirts labelled with his name – even if they’re cut with a cocoon back or to mimic the hip-thrust stance he instructed his models to adopt. Yet many of Balenciaga’s garments also have humble origins: his semi-fitted suits were based on the smocks worn by sailors in Getaria, the coastal village in Basque country where he was born. His father was one of them.

Gvasalia’s father repaired cars; his mother was a housewife. While Balenciaga was apolitical, Gvasalia wasn’t permitted that luxury. He was born in Georgia, though his family was displaced via a process of ethnic cleansing by Abkhaz separatists that ultimately expelled a quarter of a million Georgians from their homes between 1992 and 1993. He and his family relocated first to Ukraine and, with the Iron Curtain having fallen, Gvasalia’s father shifted, unexpectedly, to a lucrative business of importing hitherto restricted goods into Russia – mineral water, caviar. Fashion wasn’t such a great leap for Gvasalia, although he first got a degree in economics before going against his parents’ wishes and studying how to design clothes. He then began to work with other brands in Paris – namely Maison Martin Margiela and Louis Vuitton – before starting Vetements. It’s a far cry from the apocryphal origin story of a precocious Balenciaga, remarking as an 11-year-old on the elegance of the Marquesa de Casa Torres as she passed in a tailleur by the turn-of-the-century couture house Drecoll. Sometimes he’s 13, sometimes she’s wearing Worth. In all the stories, she allowed him to copy it, which he did with prodigious skill, and a star was born.

As Gvasalia and I speak, surrounded by remnants of the maison’s past on the outskirts of Paris, preparations are underway to disinter the literal house of Balenciaga on avenue George V. The man himself didn’t live there, of course – although his directrice of couture, an icy woman referred to only as Mademoiselle Renée and a fervent acolyte, had an apartment on the top floor. Cristóbal Balenciaga’s own home was around the corner on avenue Marceau, at number 28, but his life was in 10 avenue George V. There’s a charge to the building – an imprint remains of the events it bore witness to. Balenciaga sat there, brooding and melancholy, devising silhouettes, inventing fabrics, shifting fashion. His clothes were sewn there, in stark ateliers that his former assistant André Courrèges described in religious terms: “Pure white, unornamented and intensely silent. People whispered and walked on tiptoe, and even the clients talked in hushed voices.” Those clients saw Balenciaga’s clothes in fashion shows from which the press was habitually excluded, in oddly fanciful white salons with stucco scrolls, Louie-hooey curve-backed couches and urn-shaped lamps on plaster pedestals. In complete silence, a cabine of models of unconventional beauty – less flatteringly dubbed “monsters” by the press – paraded clothes that, in their masterful cut, transformed not only the direction of fashion, but also the ways in which people saw themselves. Sleeves sliced at three-quarter length elongated arms; collars shrugged away from the neck extended the profile – silhouettes breathed easy, bodies were free.

For the past 30 years or so, those stately salons where Balenciaga showed clothes that redefined fashion, had been stripped back to brick. Most recently, they were stacked with boxes of Balenciaga’s bestselling Triple S trainers – a symbol if ever there was one of the couture house’s recalibration to the demands of the 21st-century luxury market. “Blasphemous,” is the word used by Gvasalia. Now the boxes are gone, replaced by a breathtakingly precise facsimile of the original interior – stucco, sofas, urns and all – less reproduction than resurrection, executed by a Berlin architectural practice named Sub and based on plentiful archival footage and photographs. But it isn’t exactly right: the walls are grimy, white darkened to a dingy grey, the silken curtains tidemarked. Like those creased silk dresses and plucked embroideries, its attitude is disrespect – as if the house of Balenciaga has been left to rot.

The inspiration, Gvasalia said, was the relatively recent unearthing of an apartment in the 9th arrondissement of Paris once owned by an actress named Marthe de Florian. It was closed up at the outbreak of the second world war and only opened again in 2010: water had leaked in, staining walls, curtains had faded and greyed with dust. Gvasalia wanted the same in George V. “It has to really feel like the passage of time, which I think is the most beautiful thing,” he says. Hence a ‘patination’ team spent the month before the show basically living from the space, “spilling Coca-Cola in the morning, smoking, dipping ash a little bit everywhere”, according to Gösta Andreas Lönn Grill, one of the team’s designers, to speed up the ageing process and make it seem as if 53 years had elapsed since the white carpets were last trod. “It’s a time machine, somehow,” says Gvasalia. Or like a tomb cracked open: the Norwegian “olfactory artist” Sissel Tolaas even created a scent by taking molecules from that leather-clad elevator, from old textiles and from the key notes of the fragrances worn by clients attending those final couture shows. “They really smell like the past,” Gvasalia says.

Gvasalia’s couture ateliers are based not at avenue George V but at Balenciaga’s headquarters on the Left Bank, a cruciform building that formerly housed a hospital, built around an old chapel. Surgery meeting religion feels very Balenciaga – and Gvasalia and the atelier workers all operate wearing white cotton coats, the face masks necessary for such up-close and personal work in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic giving the scene an undeniably clinical bent. Each garment is fitted on a new cabine of models who, like Cristóbal Balenciaga’s, are unconventional: a forty-something digital-marketing strategist named Susanne Theimer from Cologne, a collector of avant-garde art called Karen Boros, the contemporary artist Eliza Douglas (who opened this couture show and also Gvasalia’s first ready-to-wear show in 2016), and Kamala Harris’s fashion-conscious, newsworthy stepdaughter Ella Emhoff. Other faces are hidden under the collection’s many giant flying saucer hats by Philip Treacy. There are also men – Gvasalia proposing couture inspired not only by Cristóbal Balenciaga’s designs but his own attire. The house collaborated with Huntsman, Balenciaga’s Savile Row tailor, on suiting in crisp barathea and fresco wools, like he would have worn. One alone required three weeks of hand-stitching to perfect. “There is not a single machine stitch on it,” Gvasalia says. “That, for me, is kind of the epitome of craftsmanship.”

“We tried to step into those pictures from the past” – Demna Gvasalia

Couture on any model’s body is a proposition for a client – an unreality, even if it isn’t worn by a supermodel. Yet Gvasalia doesn’t intend this to be a vanity project: this is couture to be bought and sold. The house has engaged a directrice, formerly of Jean Paul Gaultier and Yves Saint Laurent. She was gardening when she received the call. “I think that’s the challenge of couture today,” Gvasalia says. “It’s far from dying out. Of course, if you see couture as something for old rich ladies and don’t dust it off, then it doesn’t have a future. But if you put that craft in the spotlight, it can have a relevance. Even for the younger generation – especially when everything is available, when every brand does a logo T-shirt, that’s exactly when people start to value other things. I’m not talking about masses, it’s a small circle of people who can appreciate this, but they are there. And it does balance the rest.” By the rest, Gvasalia means the rest of Balenciaga’s offering today – the ready-to-wear, the handbags, the trainers and logo T-shirts. But the couture – which has its own label and logotype, its own packaging, and shows independently from the ready-to-wear, and only once a year – stands alone. “I like the idea of it being two separate things,” he says. “There is more of an aesthetic influence that I believe will be transmitted to the ready-to-wear. This sophisticated elegance. But not trying to mimic the complexity of craftsmanship that I can have in couture. Because it will never be possible, within the price range as well. This is why I don’t even want to try that.” He pauses. “I’d rather have couture as an inspiration.”

Relaunching Balenciaga’s couture operation is a tricky business. Haute couture requires phenomenal investment – prices begin in the upper five figures, and soar, due to the hours of handwork invested in every piece. It is entirely made to measure, for each individual client, so no corners can be cut. Balenciaga has not only employed a directrice but has assembled, from scratch, workrooms devoted to tailoring and flou – the evocative French term for light dressmaking – in the most traditional and formal manner. Every sample garment is labelled with the name of the atelier in which it is produced and the model’s name it is specifically fitted to. As Cristóbal decreed, each model wears only garments specially made for them. The house has also collaborated with craft houses and fabric manufacturers who originally worked with Balenciaga to devise new weaves and techniques: the embroiderers Maison Lesage and Atelier Montex, the textile houses of Dormeuil, Jakob Schlaepfer, Taroni and Forster Rohner. “It’s quite touching to go back to the craft,” Gvasalia says. “It died out, in a way.”

The archival references, by and large, aren’t the milestones that fashion dorks would expect Gvasalia to reimagine. There’s no rehash of the 1950 evening gown of two balloons of taffeta, the feather-embroidered extravaganzas of the 1960s, the extraordinary trapezoid four-sided cocktail dress of winter 1967 that made sitting impossible. There aren’t even the Spanish laces, the embroidered toreador boleros, the cocoon coats, those semi-fitted little skirt suits. “I didn’t use my brain so much, I used my instinct,” Gvasalia says of the design process. “Every time I listen to my gut, it’s always a decision that makes sense in the end.”

Back in the archive, off to one side, there is a massive, blown-up publicity portrait of Cristóbal Balenciaga propped against a concrete column. It is Balenciaga in the 1950s, when he was in his sixties – no longer matinee idol handsome, as when he first opened his house in Paris, but still good-looking, albeit with deep frown lines, one hand hiding a receding chin of which he was always self-conscious. Portraits of Balenciaga are rare – he was the first couturier who refused to bow after his shows and declined interview requests until after his retirement. He also never employed a press attaché. His photographic likeness seems to stare dispassionately at a beyond-life-sized mid-century portrait by Bernard Buffet of his wife, Annabel, regal in a 1959 Balenciaga ballgown. She looks like an infanta, albeit painted in a spiky, expressionist style rather than the faultless technique of Diego Velázquez, whose stately Las Meninas constantly echoes in Balenciaga’s clothing. He also admired Francisco de Zurbarán, whose work depicted not the richness of the Spanish court but the simplicity of nuns, monks and martyrs. Perhaps it was to emulate the almost sculptural draped fabrics of Zurbarán that Balenciaga challenged the Swiss textile firm Abraham to invent a new fabric, gazar, an architectural and crisp silk that held its shape like plywood. Inspired by cotton bandages, it took them three years to perfect. For a decade after its creation in 1958, Balenciaga carved shapes out with gazar, transforming women into walking bubbles, upturned pyramids or arum lilies of fabric.

An example of the latter, a sculptural wedding dress from 1967, will be revisited by Gvasalia as the finale look for his couture show. It’s an unconventionally direct homage – one of those well-avoided milestones. “I couldn’t not do it,” Gvasalia says. “It’s impossible without that. But we tried to do something else with it. We were like, ‘OK, let’s do it like this, or let’s do it like this. Let’s change the darts here.’ Trying to be more clever,” he rolls his eyes. “Or, I don’t know, like more construction conscious than Cristóbal. And we just ended up replicating the dress. There was no way it could be better.” They did change the fabric – the silk-wool mix has a worn feel, as if it had been drawn from the archives. “And we did change the hat, that particular hat, into a veil.” The headpiece, originally, was known as the “coal scuttle”, a helmet of fabric that resembles something out of Star Wars and has been ripped off endlessly since. “There is something quite absurd about the wedding dress in today’s context,” Gvasalia says. Which is strange, given that bridal gowns are often seen as contemporary couture’s raison d’être – if you’re going to spend six figures on a dress, it’s probably for holy matrimony. After all, that last dress Cristóbal Balenciaga ever made, after his couture house closed and just months before he died, was a wedding dress.

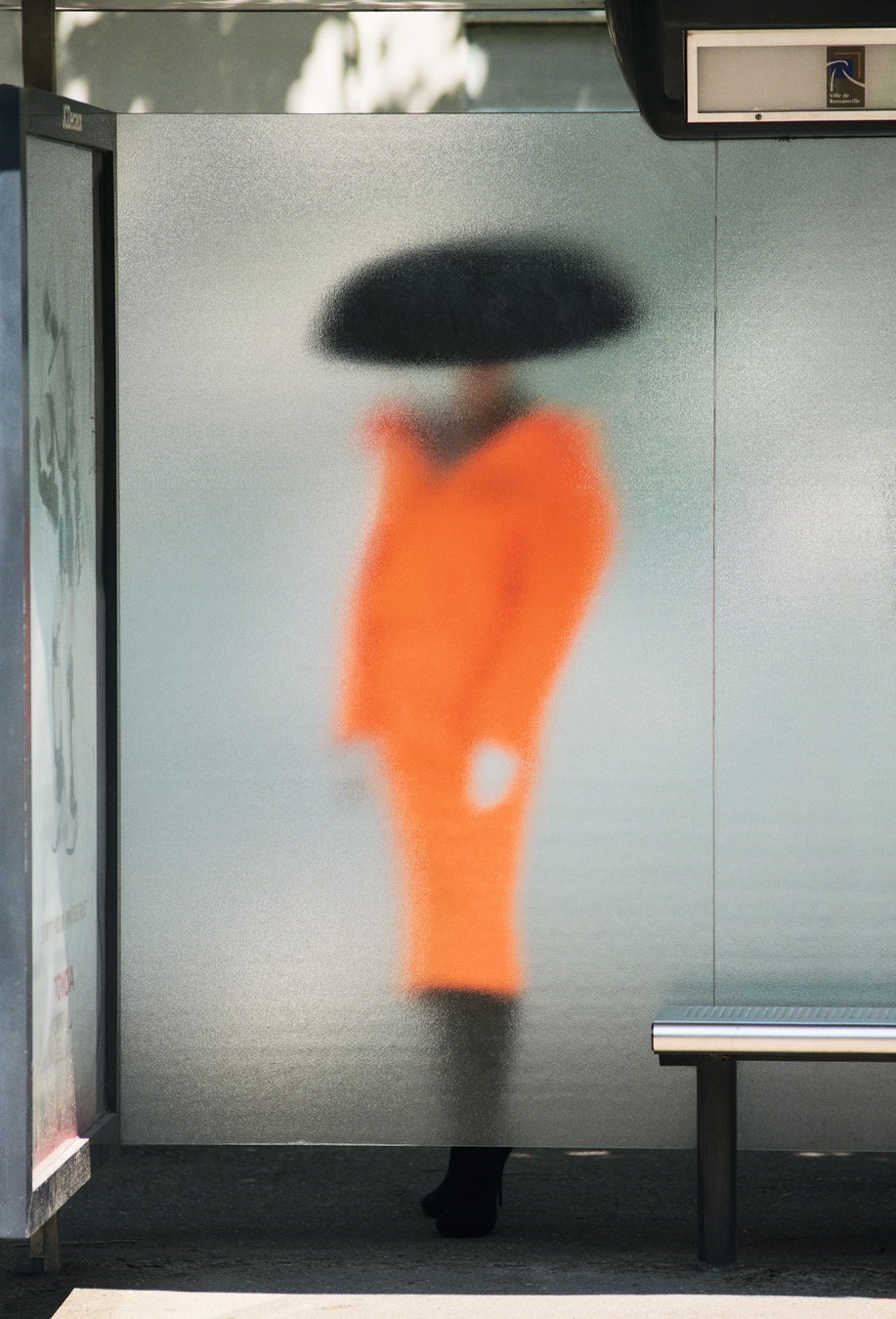

Gvasalia taps the box holding his newly made old-looking bodice, its neckline scooping shallow across an imaginary collarbone. It will later be attached to a wide skirt, worn over men’s wool trousers. “In that dress, I do reference Cristóbal’s silhouette of the Infanta, where he references Velázquez paintings,” Gvasalia says. “Luckily we do have this history, so we can build on that.” A reference to a reference – you find that elsewhere in the collection. Sometimes the reference is even to Gvasalia’s own work at Balenciaga, his translation of Cristóbal’s couture attitude into ready-to-wear bouncing right back to couture again. Take look 17, a hazmat-orange gabardine suit with the jacket shrugged off the shoulders, neck wrenched wide open – it’s an open reference to his debut Balenciaga show, where he pulled the necks apart on trench coats and padded jackets to emulate the shape of grandiose opera coats. “But this orange jacket, it required so much work that could never have been done in ready-to-wear,” Gvasalia says. “In my first collection for Balenciaga, when I started opening the shoulder line ... that was a very easy construction. You made a huge dart, basically, swinging the shape to the back. But when you wear it, it doesn’t behave the same way. This was like an upgrade, completely crazy, pattern-making acrobatics.” He smiles, shrugs. “It’s couture.”

“For me, it was the beginning of a new era. I’m not talking about Balenciaga, but about myself as a designer. It was a moment I have been looking forward to and been quite afraid of” – Demna Gvasalia

Two months later, the first Balenciaga couture show since 1968 – the 50th in total, a satisfying number – takes place at 11.30am on the 7th of July. The context is historical: the recreated salons are filled with spindly gold chairs, a carnation placed on each. The air does indeed smell old. “I wanted to underline the timelessness of couture,” Gvasalia said. “We tried to step into those pictures from the past.” The show was staged during the first physical haute couture presentations since January 2020. That was important for Gvasalia – he waited to showcase the collection until he could do so in person – what’s another few months when you’ve waited since 1968? “The screen makes everything so flat – and of course, you cannot see that broken embroidery, the craft,” he says. “There is something quite majestic about couture being worn.”

When the show began, no one really realised. It began without the thud of music common to most shows, and especially to those of Balenciaga under Gvasalia – his husband, Loïk Gomez, a French musician under the moniker BFRND, creates all the soundtracks. This collection, however, would be shown in silence, another unexpected homage to Cristóbal and to haute couture tradition. “Cristóbal loved silence,” says Gvasalia. It’s quite intimidating. “Here it’s all about the garments.” Silence, he says, makes the experience not less but even more intense. “I wanted to use microphones, to amplify. But that would be fake. With a lot of fabrics we’re using, you do hear them. There are trains, a carpet that rubs. It’s almost fetishistic.”

The collection dances between those different interpretations of attitude, between respect and repudiation. Models wear embroidered evening gowns, sure, but also the tailoring based on Cristóbal’s personal wardrobe, while Mona von Bismarck opera coats morph into the ski anoraks he sewed in his own ateliers. Male models walk in high heels – Gvasalia wanted them to change the posture and deportment of the wearers, many of whom had to be specially trained. “The gay guys were fine,” Gvasalia says. The collection’s striking, sometimes searing colours are even drawn from Balenciaga fabric swatches in the archive – the orange, the pink, an electric blue, sealed in cardboard boxes so untouched by time. Polka dots come from the archives too. Gvasalia’s couture T-shirt is in padded silk, with a matching stole. It’s an accessory he uses a lot, a couture gesture. There are also lots of gloves, sometimes built into tops to streamline and perfect. Jewellery is based on original pieces displaced, so elaborate spherical brooches can become earrings or perhaps cocktail rings. Pauline de Rothschild once stated that the wit was on the head chez Balenciaga – Cristóbal’s milliners were also his life partners, Ramón Esparza and Wladzio Jaworowski d’Attainville, so they were perhaps afforded more liberties than most. Here, the sole headpiece is a Treacy dome, like a shallow inverted fruit bowl, flocked with velvet or high-gloss lacquer. “It’s like a car varnish,” says Gvasalia. “I wanted to have some kind of almost futuristic touch. A bit alien.”

Jeans in Balenciaga’s couture salon are also alien and futuristic. Gvasalia’s denims are woven in Japan, riveted and buttoned in sterling silver, lined in silk. “People think I literally just take one thing and put a brand name on it,” Gvasalia says. “It’s not that at all.” There is, perhaps, a sense that Gvasalia – still, after six years – feels the need to prove himself worthy of the Balenciaga name. “Accepting the wedding dress – the ingenuity of how this wedding dress was made in the 1960s – was letting go of that fear of not being innovative in every look. Not transforming everything that I took for this collection as a reference from Cristóbal into something completely new,” he says. “For a designer like me, that’s difficult.” Following Gvasalia’s rumpled Astroturf-green opera coat and the fucked-up Infanta evening gown, Cristóbal Balenciaga’s wedding dress swept through the salons of his house. He hadn’t changed a thing.

After the show, a lull. The evening afterwards, there’s a dinner in the new art foundation established by the Pinault family in the centre of Paris. Gvasalia wears the high-heeled men’s shoes he had debuted barely nine hours earlier. There’s a performance by Bryan Ferry – “I thought he felt quite couture,” Gvasalia said, laughing. The next day, he travelled back to Zurich with his husband.

“For me, it was the beginning of a new era.” Gvasalia sounds a bit fuzzy on the phone from Switzerland. But he’s pleased. “I’m not talking about Balenciaga, but about myself as a designer. It was a moment I have been looking forward to and been quite afraid of.”

Is he still afraid? “I feel at peace,” Gvasalia says. “I never really knew that feeling within the context of my work, to feel at peace. I always felt quite agitated, nervous, before the show, anxious. I had this anxiety before the show yesterday – I forgot how it feels, actually. It’s been over a year since I had to do a show in real life. It felt again like the first time – something physical, in your stomach, almost. I couldn’t understand if I liked it or not, and just before the show I realised I love it. It’s the tension – fashion is about a tension, and then you release. I felt like I released something that has been incubating in me for a long time. Not only one year, I think much longer. That release brought me to this feeling of peacefulness.”

Gvasalia breathes out. “It’s not really about that collection so much as my personal relationship with fashion. Through couture, I found peace with it.”

Hair: Akemi Kishida at Blend Management using ORIBE. Make-up: Anthony Preel at Artlist. Models: Binta Diacko at Fever, Marie Agnès Diène at The Claw, Adama Konate at Girl Mgmt, Azenor Le Dily at Supreme, Gritli and Sori at Keva Legault, Marius and Boris at Tomorrow Is Another Day and Lisa Williamson at The Face. Casting: Julia Lange Casting. Casting associate: Mathilde Curel. Photographic assistant: Léa Guintrand. Styling assistants: Emmanuelle Ramos and Matthieu Bertorello. Hair assistant: Yulia Pantiukhina. Make-up assistant: Azusa Kumakura. Production: TheLink Mgmt. On-set producer: Gwenaelle Wieners

This article appears in the Autumn/Winter 2021 issue of AnOther Magazine which will be on sale internationally from 7 October 2021. Pre-order a copy here.