The story of Dazed & Confused is the story of a magazine: how, over a period of 30 years, a small zine morphed into a global media group. But it’s also the story of a gang of club kids at the epicenter of an underground arts scene, who captured the spirit of Britart and Britpop and changed the face of publishing, launching the careers of countless journalists, photographers, stylists and even designers in the process. It’s the story of a community of creative rebels – centred around a punk, DIY, and youth-driven ethic – who infiltrated the fashion and cultural establishments, breaking all the rules and simply making it up as they went along.

The 1990s

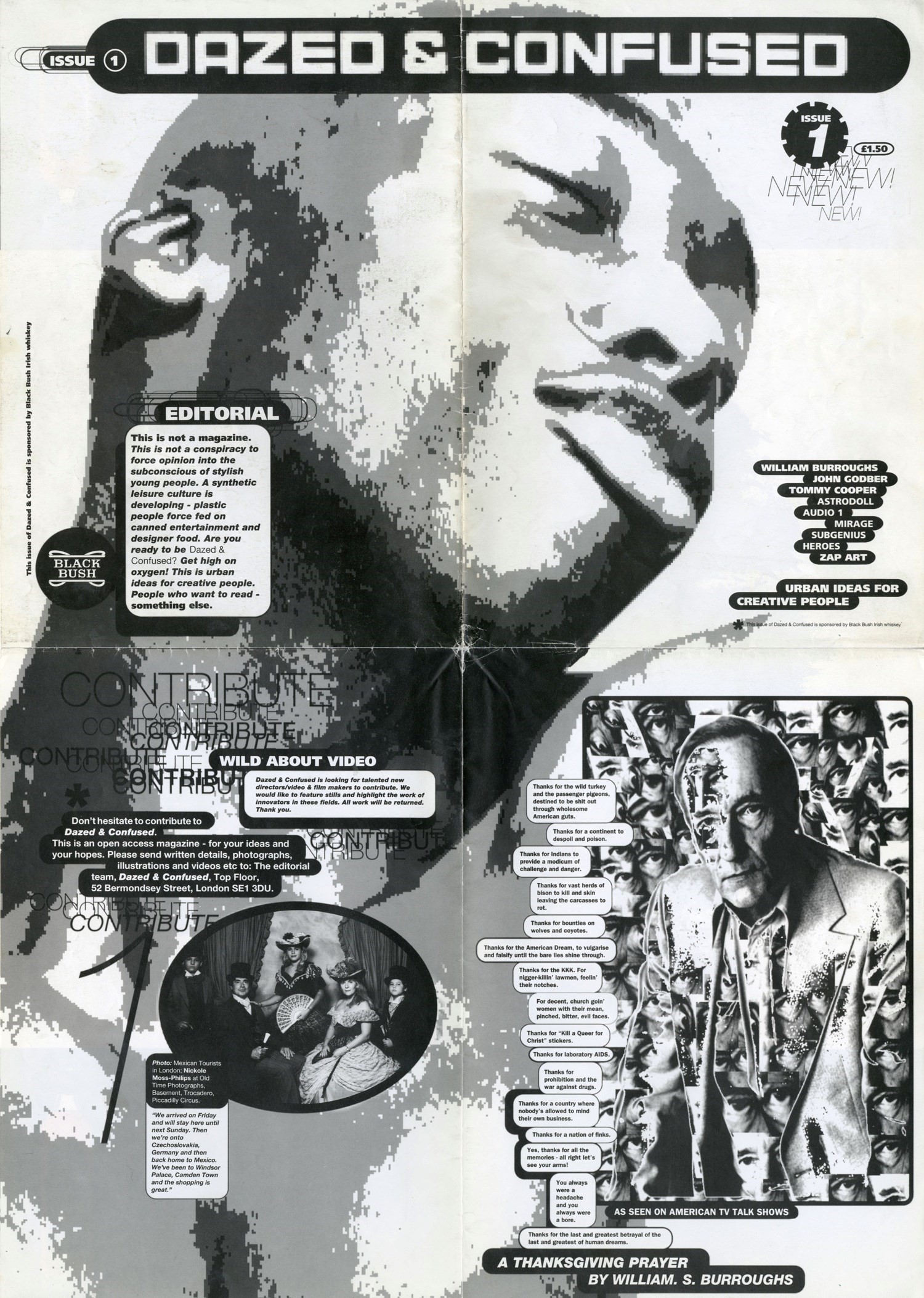

The story began with a phone call. In 1991, a photographer called Rankin Waddell (then 23) rang a journalism student called Jefferson Hack (then 18) about working on the student magazine. They met up in the canteen of their university, the London College of Printing (now the London College of Communication), and immediately hit it off. Within months Jefferson had dropped out to work full-time on the project, which by that time had evolved into a zine named Dazed & Confused, after the Led Zeppelin song. “This is not a magazine,” declared the tagline on the cover of the first issue. “This is not a conspiracy to force opinion into the subconscious of stylish young people. A synthetic leisure culture is developing – plastic people force fed on canned entertainment and designer food. Are you ready to be Dazed & Confused?”

As it turns out, people were. First based out of the LCP student union, Jefferson and Rankin soon decamped to an office in Soho. The space was small, cramped and chaotic, with one desk formed out of a sheet of MDF laid clumsily over a kitchen sink. However, the location made up for the less-than-ideal office environment: the photographer Corinne Day lived upstairs and they were just down the road from the Atlantic Bar & Grill, a honey pot for the city’s creative community, which became a second office of sorts.

They were at the beating heart of London’s burgeoning arts scene, surrounded by people from the worlds of fashion, art, music and film, who were all coalescing in what was an extremely exciting moment for British creativity – a moment the media later dubbed ‘Britart’ and ‘Britpop’. In the pages of Dazed & Confused, Jefferson and Rankin captured the zeitgeist in a way that no other publication did, running famously hedonistic club nights to fund the magazine.

It was through clubbing that they first encountered many of their collaborators (Jefferson has since told AnOther, “I met practically everyone I worked with in nightclubs, and I mean everyone”). This includes Katie Grand, the legendary editor, formerly at LOVE, now at Perfect. A Central Saint Martins student at the time, Katie remembers Rankin as charming and interesting and began hanging out with him and Jefferson. She started to date Rankin soon after and they ended up living together for two years. This though, was the original trio: Rankin looked after the photography, Jefferson the words, and Katie the fashion.

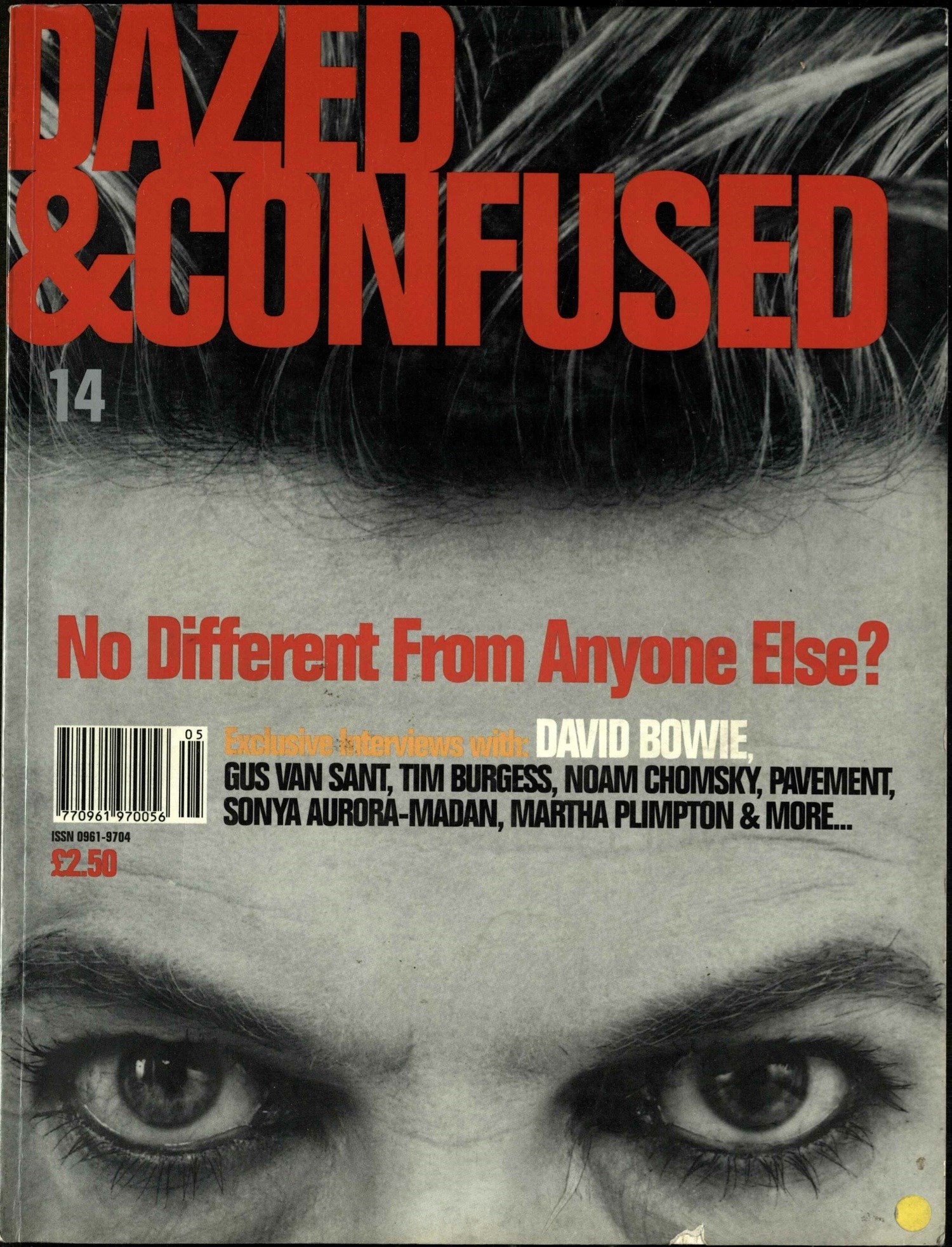

Despite being known more as a fashion magazine now, the publication was then focused on music and culture. Rankin became friends with someone who worked at Universal Records and, through him, booked cover stars like Beck, Bono and Bowie. They put their friends in the magazine too – artists like Jake and Dinos Chapman and Damien Hirst, and musicians Björk, Blur, Oasis, Portishead, and Pulp. “It was hard to do fashion then,” Katie recalls. “They’d always cut the fashion pages.” She says they were interested in concepts more than fashion for fashion’s sake, and didn’t want to emulate the club kid documentation that i-D and The Face had pioneered. Still, she had the opportunity to “flex in public”: she shot Madonna, published Mert and Marcus’ first collaborative work, and helped launch the careers of multiple young designers, many of whom she studied at Saint Martins with. Katie also says she learned the nuts and bolts of putting a magazine together during this time: from repro to bleed and finances. With just five people working on it by then, everyone did everything.

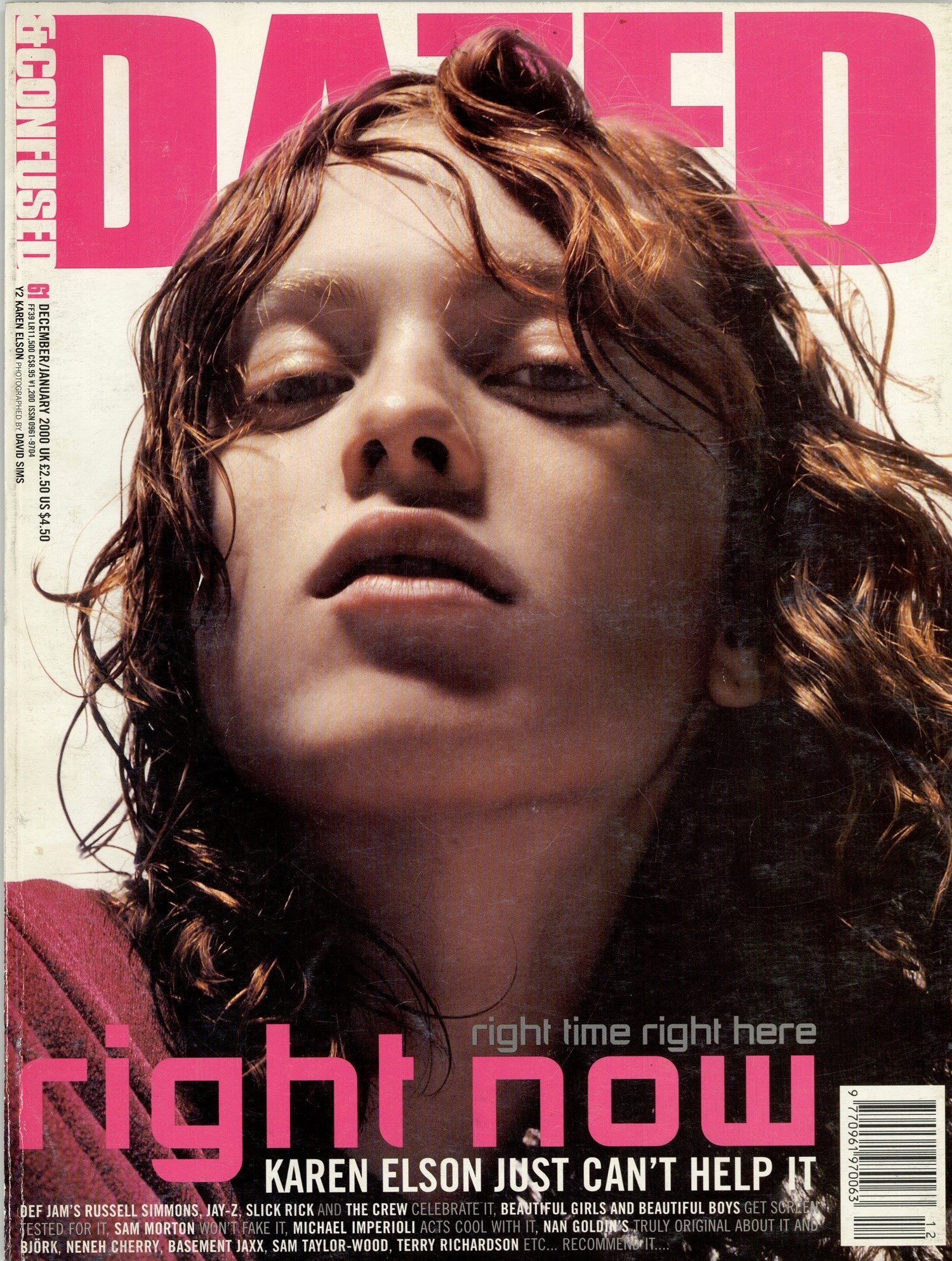

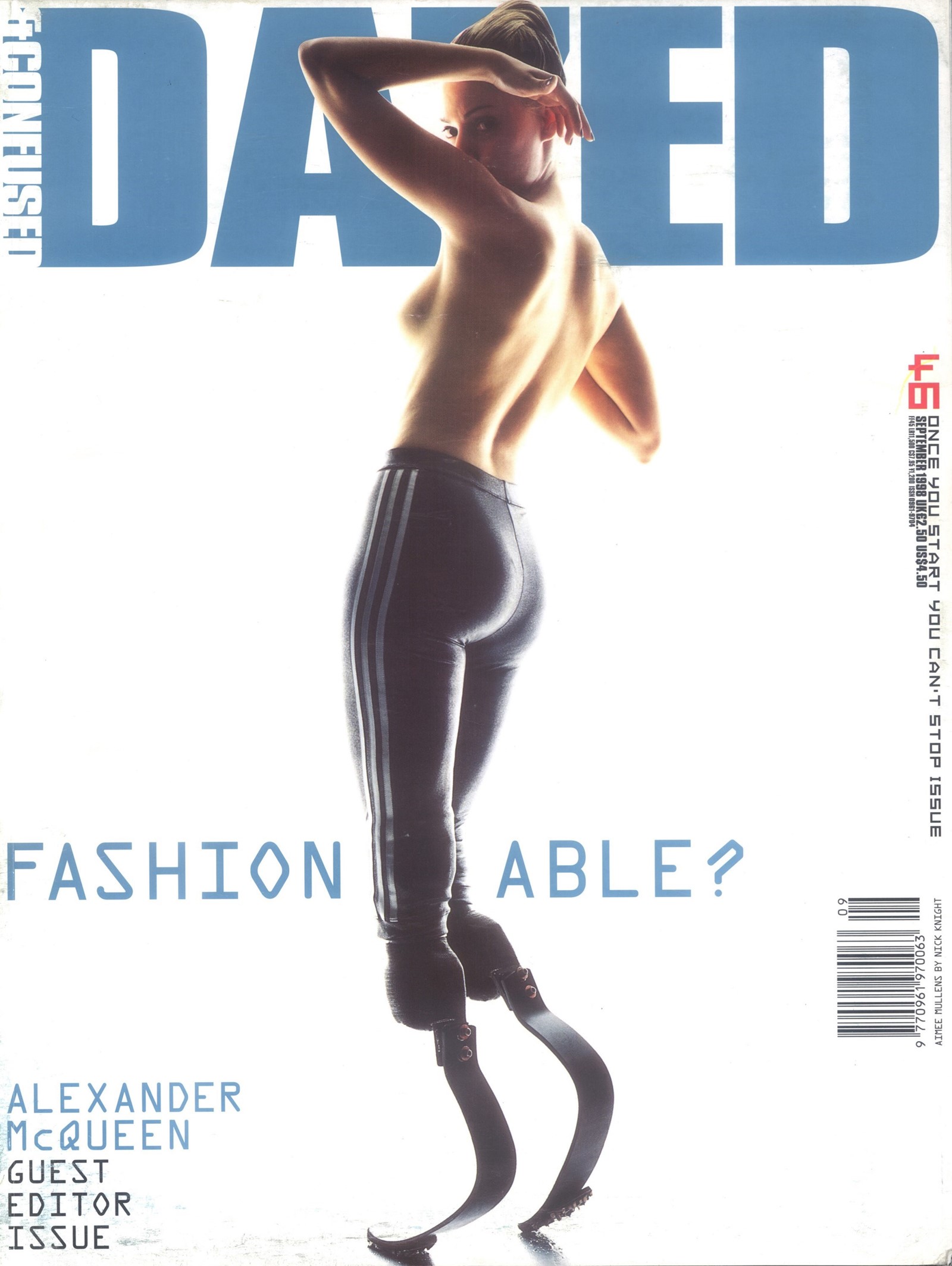

The now renowned stylist Katy England – who worked closely with Alexander McQueen and later, Riccardo Tisci – met Jefferson and Rankin around 1994, outside of that Soho office. Originally from Manchester, Katy was working at the Evening Standard at the time, but Rankin asked if she’d like to do the door at one of their club nights, held in a basement club in Leicester Square called Maximus. She agreed and later Rankin asked her if she’d like to shoot with him. She was looking for a creative outlet so leapt at the opportunity, and has styled for Dazed and its sibling titles AnOther Magazine and Another Man ever since. The opportunity allowed Katy to shoot with photographers that she’d always dreamed of working with, from Corinne Day to Nick Knight, Mario Sorrenti, Steven Klein, and David Sims (her Karen Elson cover story with the latter remains a highlight). Whoever she was shooting with though, the heart of her work was about reflecting what was going on in culture; in the creative community that she and the rest of the Dazed & Confused team were immersed in. It’s an idea that remains an important part of the magazine to this day. “I was living it,” she says. “What I put in the magazine was my life.”

This includes collaborations with McQueen. From the early days of his career (they met in 1994), England worked on his collections and shows, and on the (September 1998) issue of Dazed & Confused that the designer guest-edited, which featured Paralympian Aimee Mullins on the cover. This cover remains one of the most memorable – and meaningful – in the magazine’s 30-year history, preceding many of the conversations around diversity and inclusion.

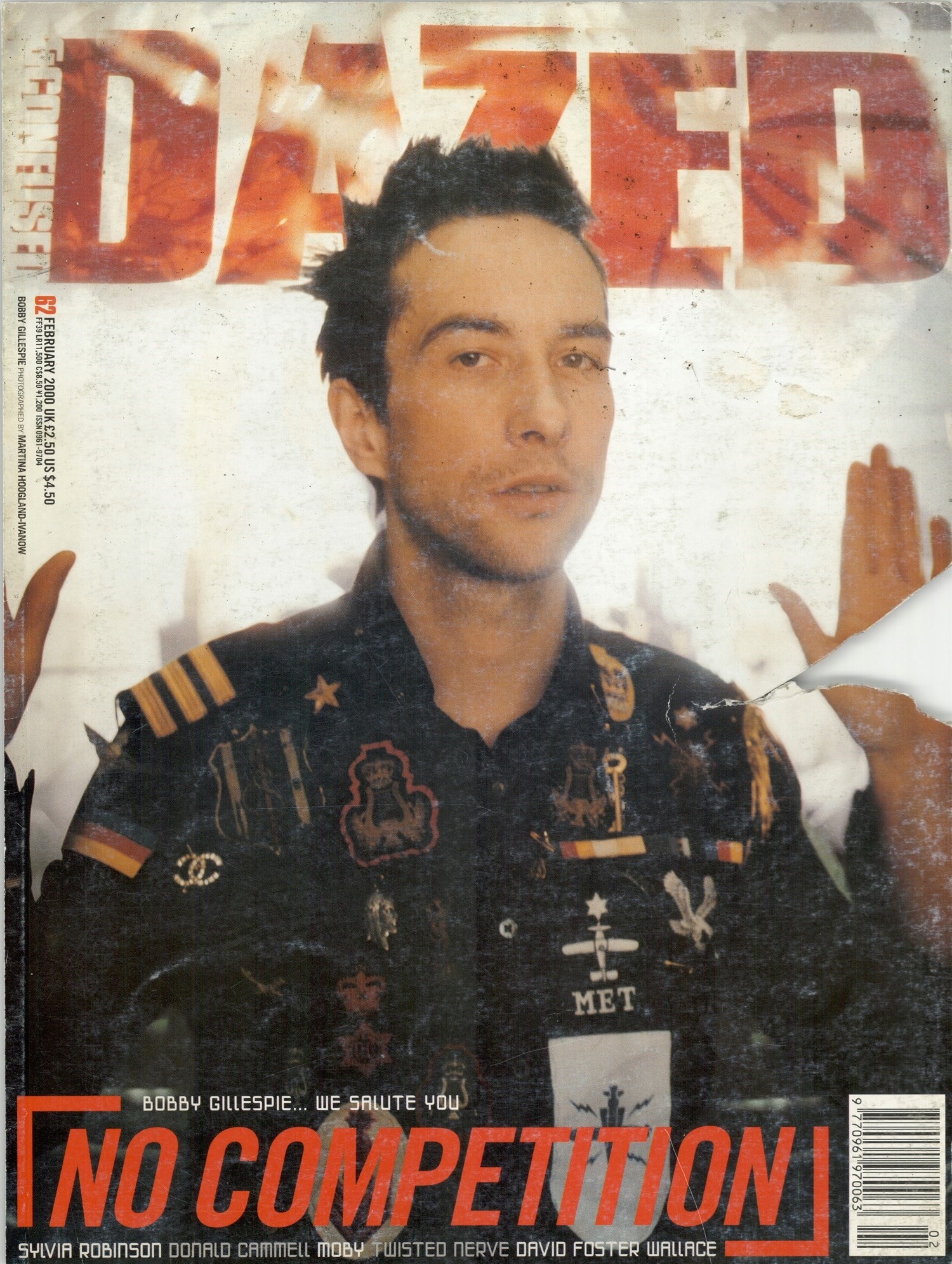

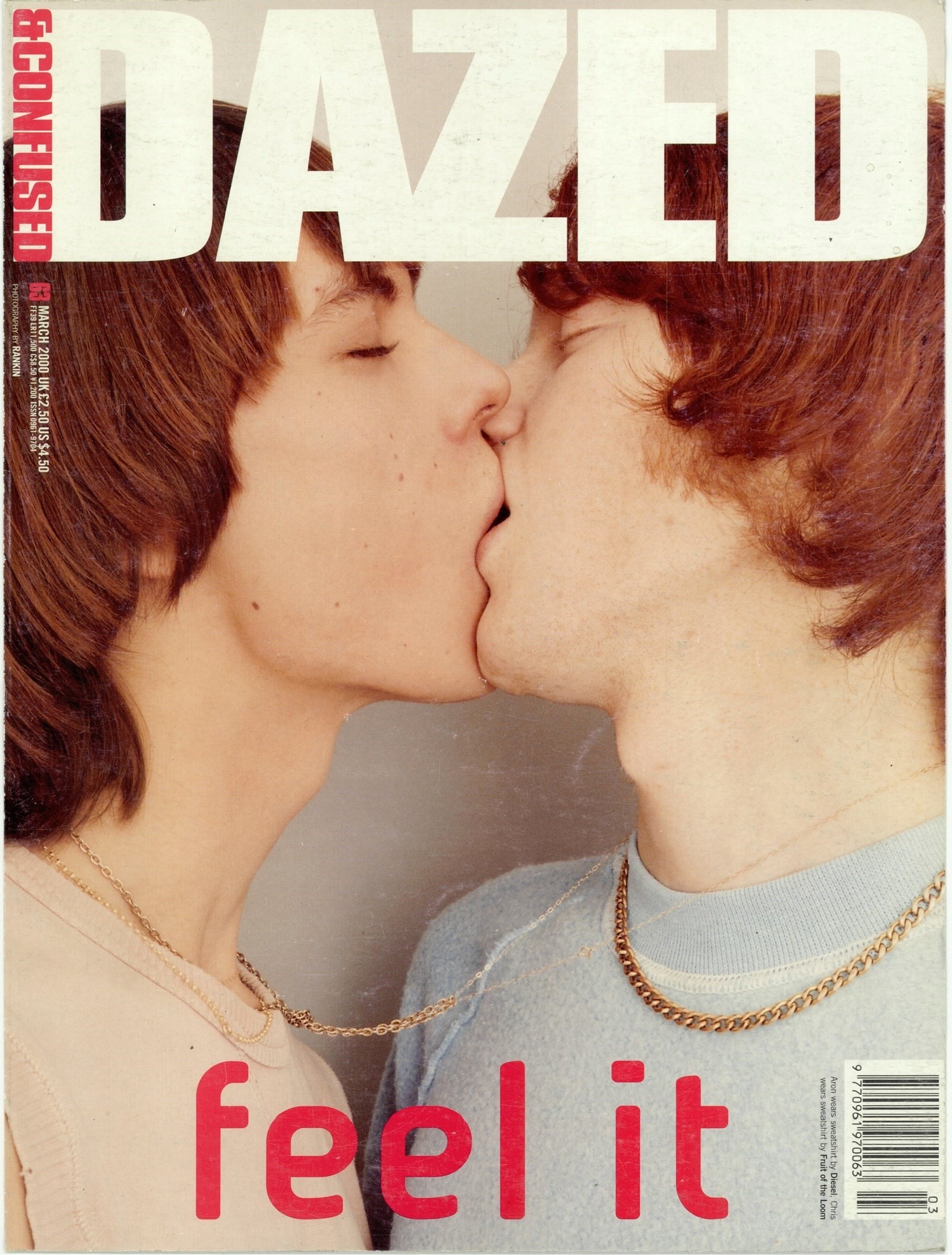

Alister Mackie began assisting Katy in 1995, when he was still a student at Saint Martins, later becoming a contributing fashion editor to the magazine, and then senior fashion editor, before going on to become creative director of Another Man (and holding consultancies at Louis Vuitton during Kim Jones’ tenure, Marc Jacobs for ten years, Lanvin with Alber Elbaz for 12 seasons, Fendi with Silvia Fendi, and Alexander McQueen with Sarah Burton). Among cover stories with Bobby Gillespie and Blondie, he shot an eight-cover story for the March 2000 issue with Rankin – before multiple covers were commonplace – featuring gay, lesbian and interracial couples kissing. Among the most seminal – and provocative – Dazed covers, these images captured the hedonistic spirit of these early days. “I like the sentiment and it being super simple. It’s not saying too much,” Alister says. “In the cast, there’s Jamie Del Moon who I loved and worked with a lot – he used to come and stay and hang out with us; and Zora Star who I worked with a lot too and did amazing work with Alexander McQueen. Yes they were models, but they were more than that, too – they were like-minded people, who were up for the project. They understood it, thought it was a fun thing to do and liked the message. Nobody was especially political at that time, they just weren’t, it wasn’t a thing and that wasn’t what it was about.”

Cathy Edwards is another seminal figure of these early days. She joined the magazine as assistant to Katie Grand in 1996, and worked as fashion director from 2003 to 2007, inheriting the title from Katy England. “I got there in March and stayed all through the summer assisting,” she told AnOther Magazine’s editor-in-chief Susannah Frankel who was first commissioned to write for Dazed & Confused by Katie Grand in 1997. “I remember Katie telling me not to bother going back to college – ‘We [Katie, Rankin and Jefferson] didn’t go back to finish our degrees. What a waste of time.’ But I thought I ought to crack on.” And that’s exactly what she did. After graduating from Brighton University, Cathy became known for creating work that was imaginative, inventive and quietly subversive. “Everything was a bit shabby. Everything we hated was commercial. It was sometimes seen as a little serious but actually there was always humour in it. It was always quite dry.” Cathy died in 2014, but it’s easy to see how her legacy lives on in the work of the editors that worked under her from Karen Langley to Nicola Formichetti.

The 2000s

Dazed & Confused was one of the reasons Nicola Formichetti moved to London. “I always wanted to be part of that scene,” he says from Los Angeles, which he now calls home. “Music, fashion, style, art – all together.” Around the year 2000, he met Katy and Alister in the forward-thinking fashion boutique the Pineal Eye, which stocked all the avant-garde brands of the time (Katy and Alister would come in to borrow clothes for shoots). It was a fateful meeting: they asked if Nicola would like to look after the ‘Eye Spy’ page of the magazine, and he quickly became a regular contributor, rising the ranks to fashion director by 2005 and creative director by 2008.

“They never told me what to do,” he recalls of the creative freedom he was given by Jefferson, Katy and Alister. “They just said, ‘We trust your style, do what feels right for you. Create a magazine within a magazine; make a world.” These values of freedom and trust remain core tenets of the magazine – one of its greatest strengths and one of the key reasons for its success. Nicola says that they prized individuality instead of forcing people to conform to a certain set of rules. “It was about being yourself.” Working and playing very hard, Nicola learned to work with extremely limited time and resources. “I exist today because of that. I have no fear of taking on projects now.”

By 2008, Dazed had moved to a converted garage on Old Street, where it would remain until 2016. Not an office in the traditional sense of the word, in this space the Dazed team would work, party, shoot, smoke and more. Shoreditch too was very different from the gentrified dystopia that is today. There was no Silicone Roundabout, no polite shops, cafes or restaurants. I remember one old colleague saying that when they moved to Old Street, the only place to buy lunch was the Shell garage up the road and all you could get was a ham sandwich. All this meant that the area was dirt cheap – it attracted an eclectic community of designers, artists and musicians, in what Nicola remembers as a “merging of rebels”.

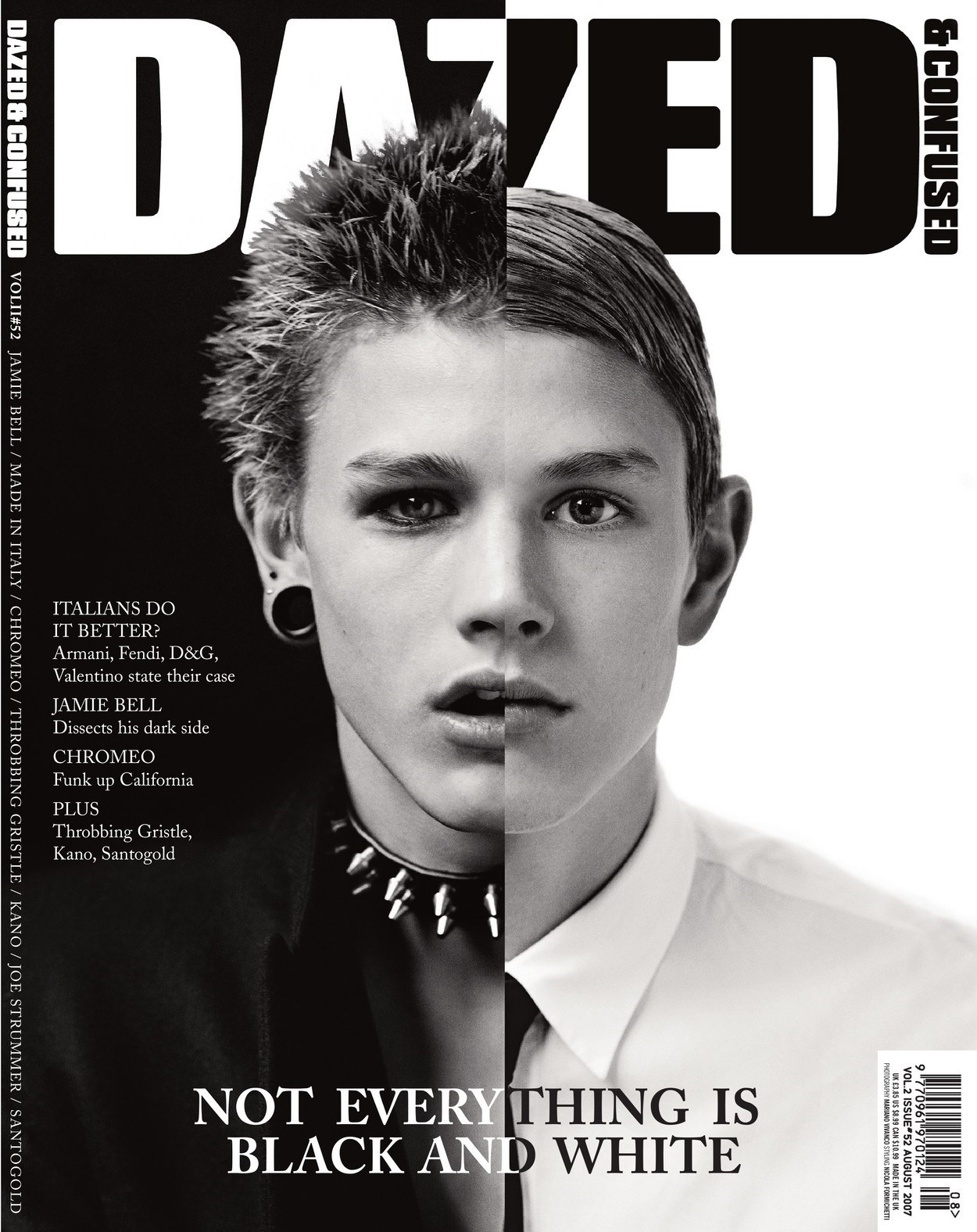

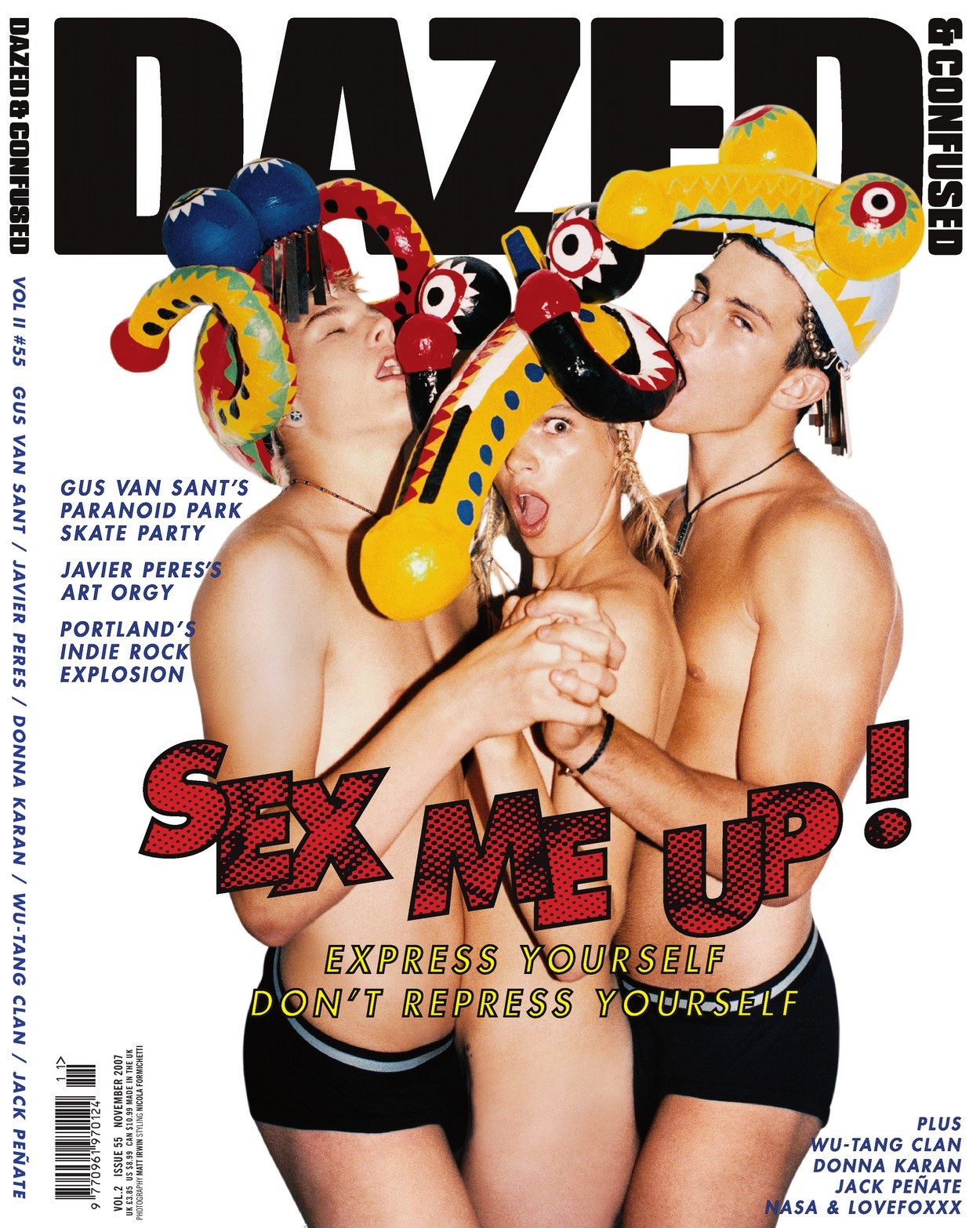

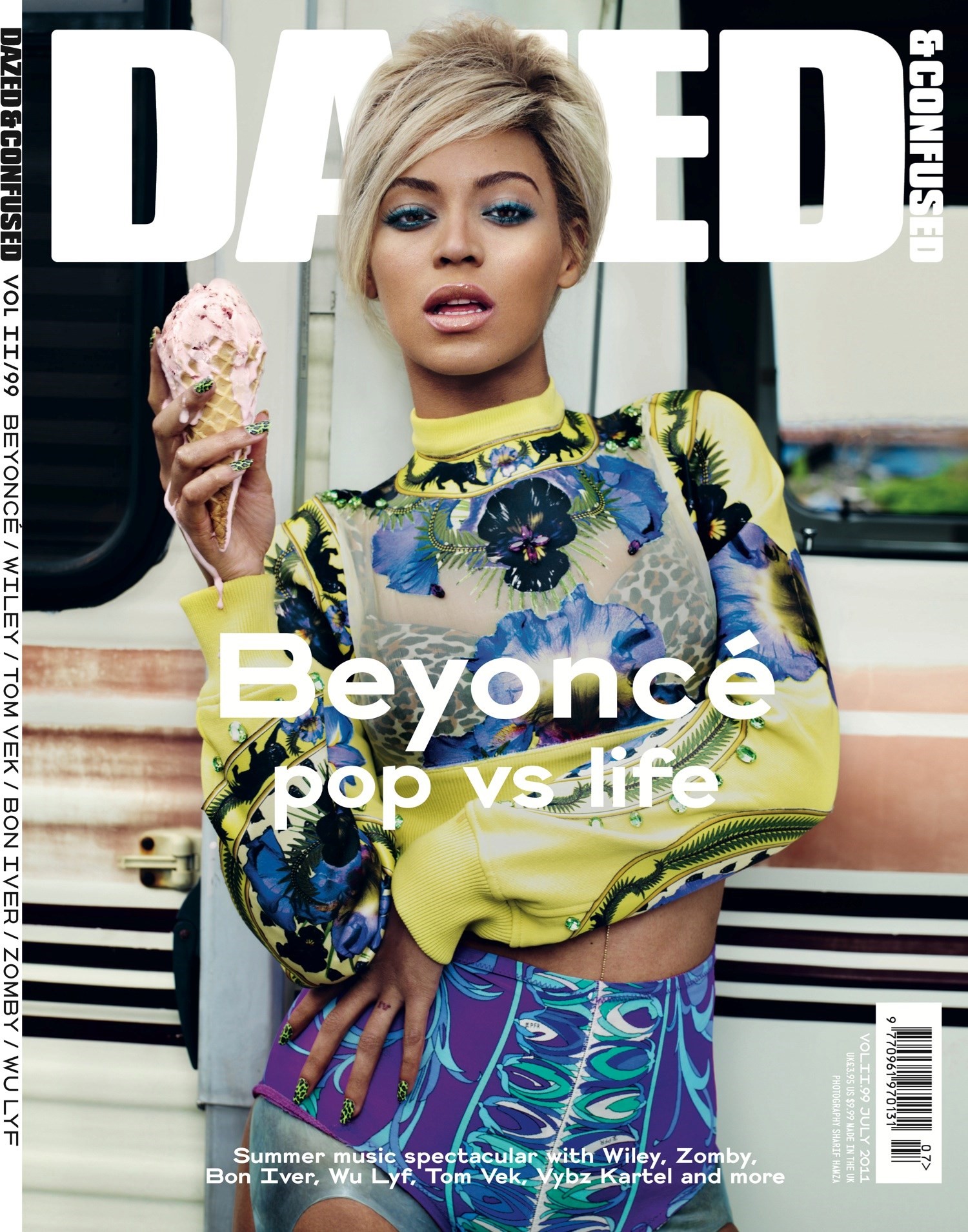

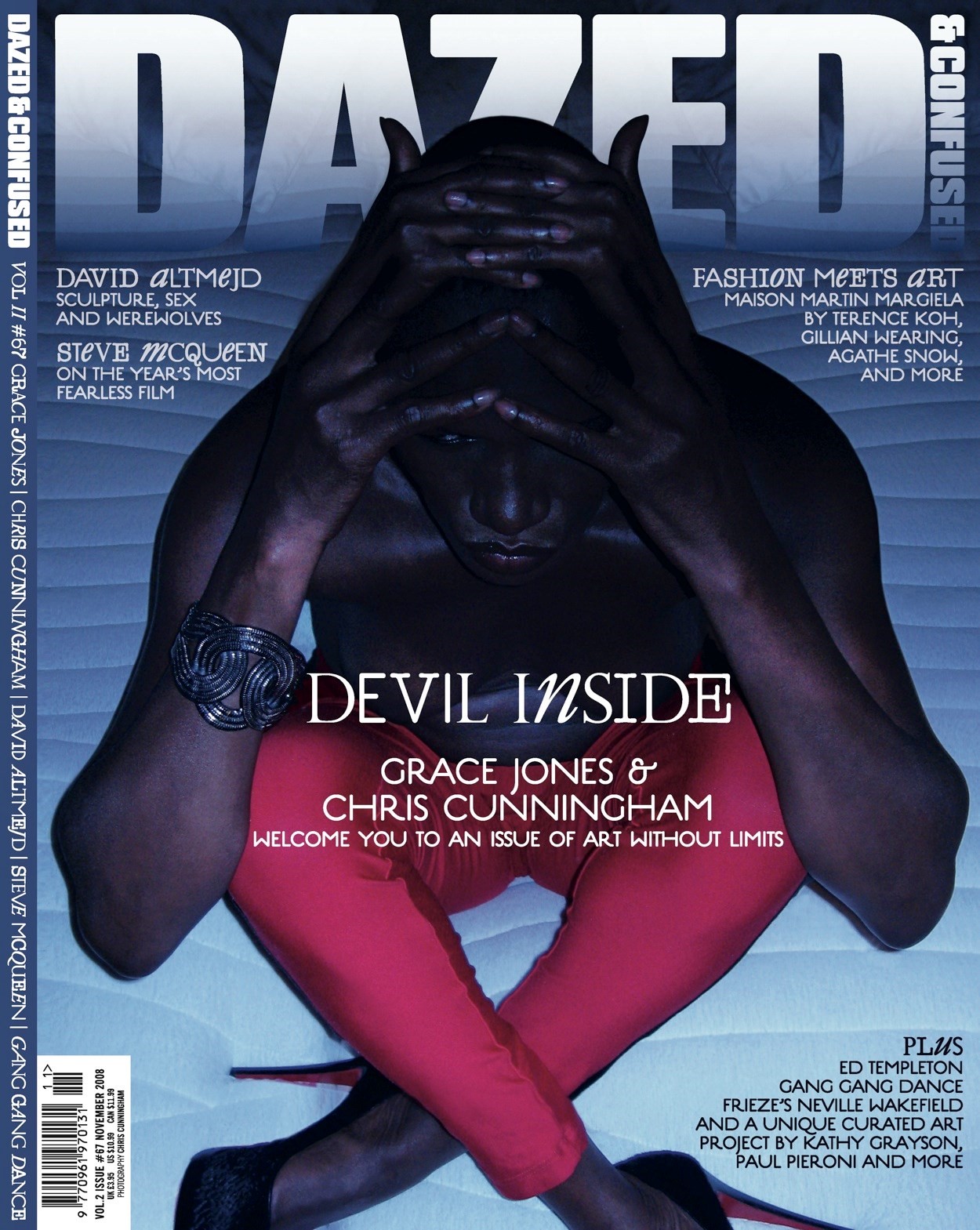

Nicola reflected this in the pages of the magazine, championing people from across the arts in a way that was visually simple and straight to the point, but colourful and concept-driven, fun and pop-y. He shot the model Luke Worrall for his first as creative director and Luke again with Anna Brewster and Florian Bourdila, in another of his most memorable covers, captured by the late photographer Matt Irwin. It was around this time that Dazed started shifting its focus, moving from music and DIY avant-gardism and radicalism to fashion and contemporary pop culture. Beyoncé starred on the cover, along with Grace Jones, Justin Timberlake, Madonna and Missy Elliott.

Susie Lau – better known by her internet name Susie Bubble – joined Dazed towards the beginning of Nicola’s era. One of the early fashion bloggers, Susie was brought on by the then digital director Alister Allen, who was looking for someone digitally forward who hadn’t come through the traditional magazine route. She was tasked with growing Dazed Digital, then in its very nascent stages, and laid the foundation for what the website is today. Before many other print magazines – particularly style titles – were doing this, she ramped up the volume of content they were publishing, firm in the conviction that the website should reflect the magazine but not mirror it; that it had to go beyond it, broaden its scope and widen its appeal, without losing the spirit of the publication.

This was the late Noughties, and the internet was still relatively new, so she and the team explored and experimented, unencumbered by set ways of doing things. And it worked: the numbers grew and Dazed became one of the first fashion and culture magazines to grow a significant online audience. Susie says that the office environment lent itself to this idea of experimentation. “Dazed is very all hands on deck. The office in Old Street was already conducive to a Wild West environment, with people feeding off each other’s energy. It’s a dynamic chaos. A chaos that works.”

The 2010s

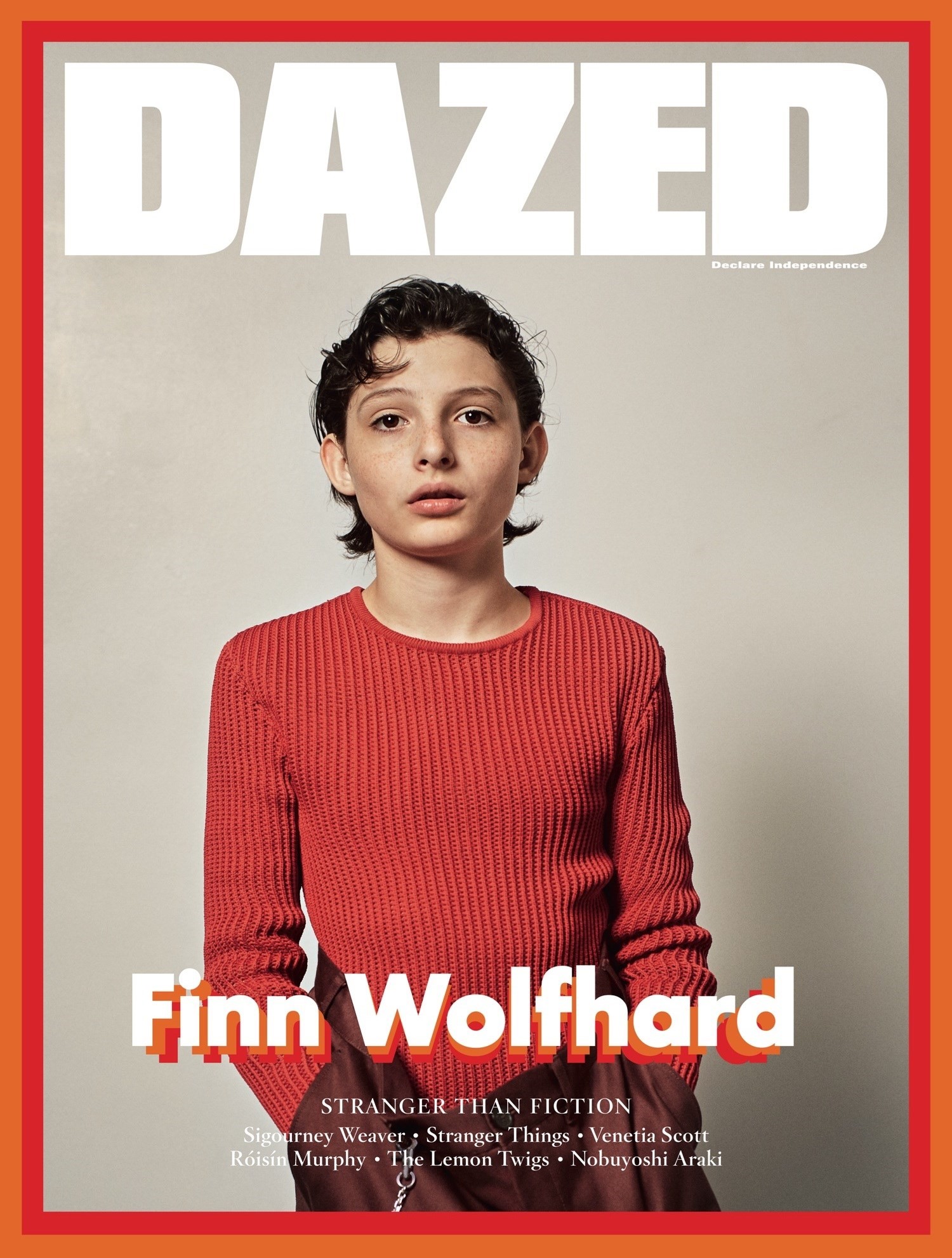

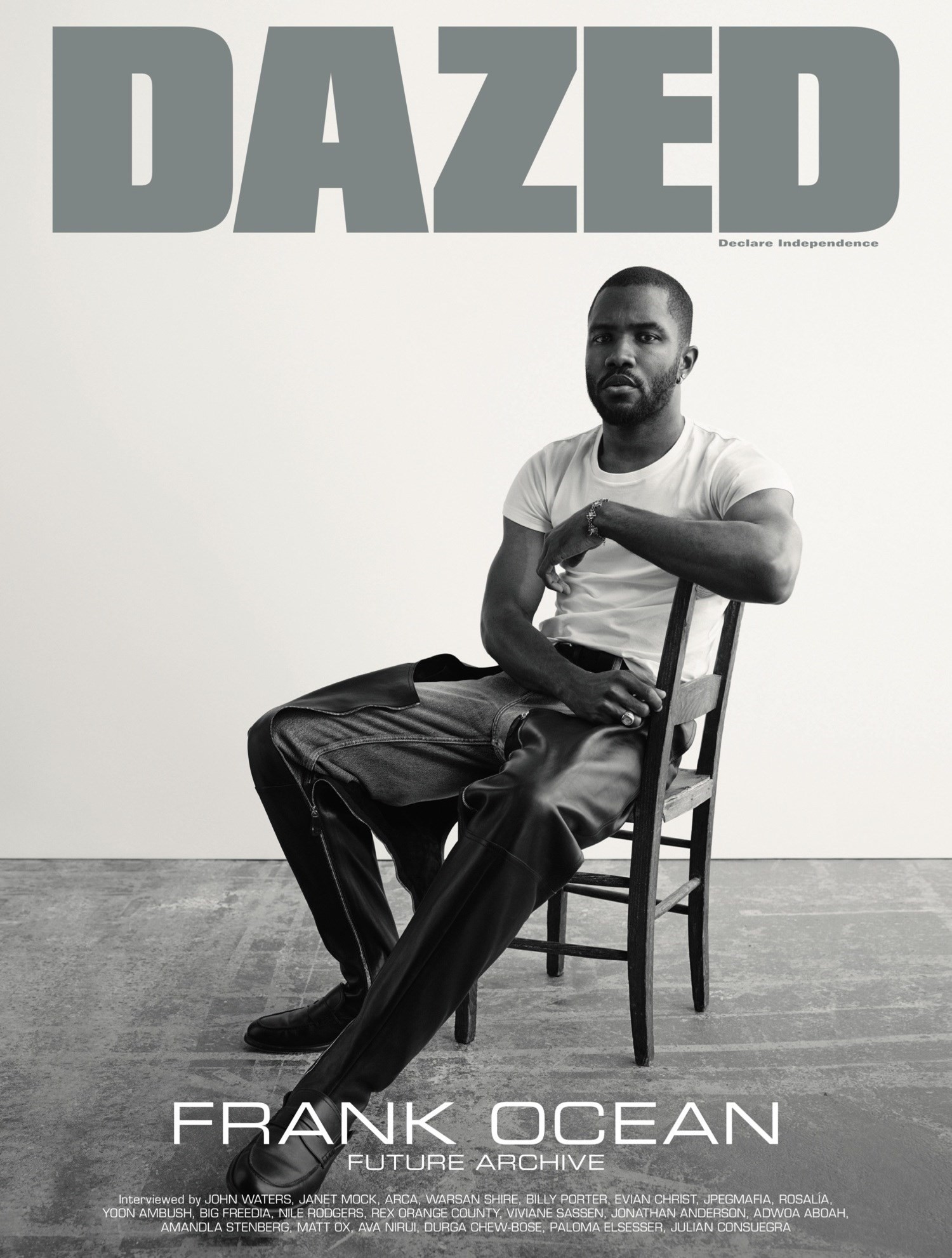

As the print magazine informed the website, so the website – and the internet more broadly – slowly began to inform the magazine, while the Twenty-Tens rolled on. Isabella Burley, who joined Dazed as fashion features editor in 2013, and became the magazine’s youngest ever editor-in-chief at the age of 24, just two years later, says that there was both “confusion and excitement” about the internet, which at the time was still a relatively new – or less all-encompassing, by today’s standards – phenomenon. However, it connected them with a new network of contributors. Having always been a London- or at least British-centric publication, the magazine started to look abroad, particularly to the US, in a much more intentional way – partly because of the senior fashion editor (and later fashion director) Emma Wyman’s links to New York’s fashion scene. Isabella says they were interested in how the London community and its spirit was infiltrating other places.

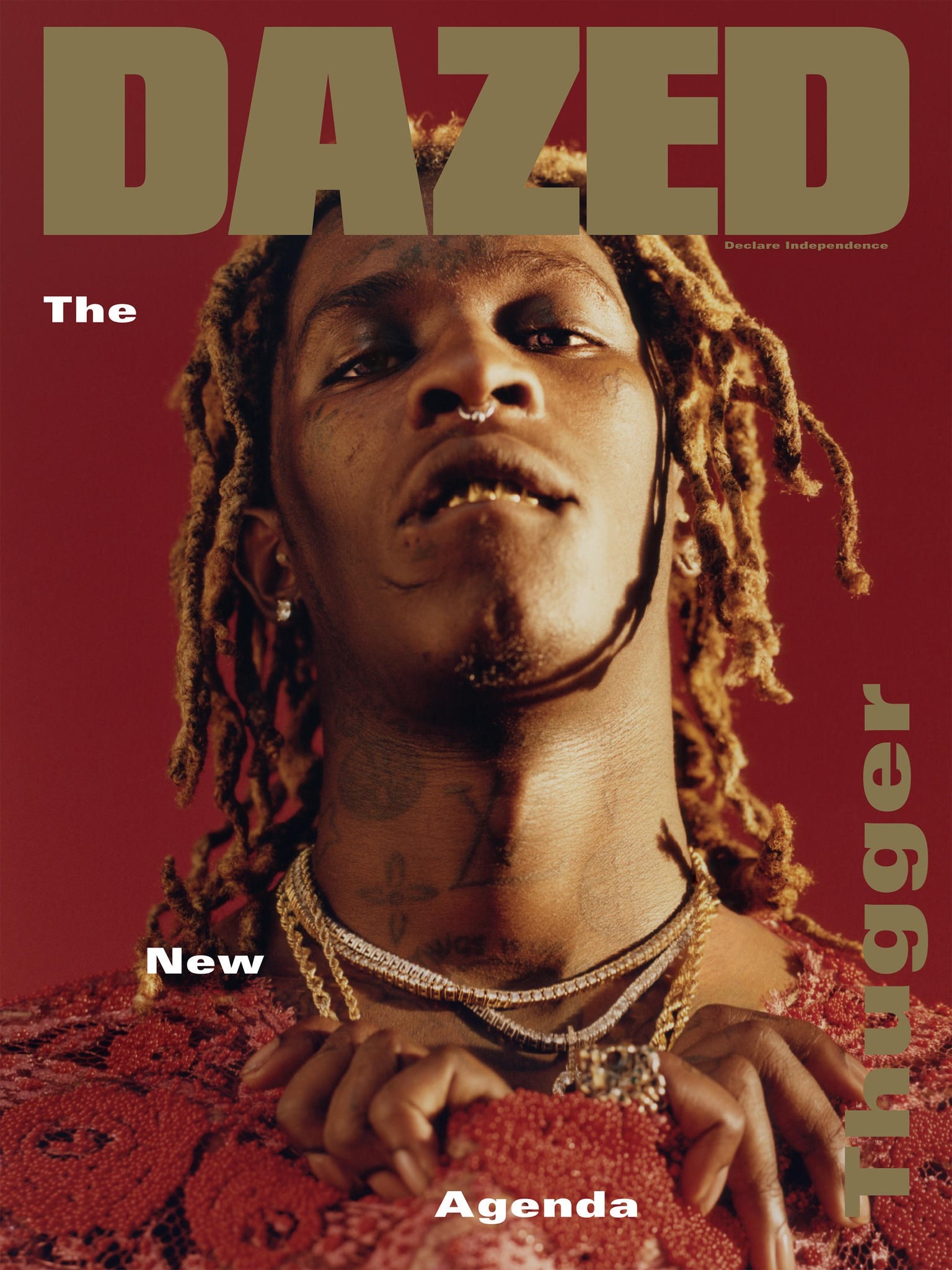

“We wanted to reflect the times we live in,” she explains. “Our contributors; their communities and their worlds. We wanted to have a lens on that.” Isabella worked alongside Robbie Spencer, who had joined Dazed as an assistant to Bryan McMahon back in 2006, and rose to become fashion director alongside Katie Shillingford and Karen Langley in 2013. In 2015, Robbie was appointed creative director alongside Jamie Reid who was named art director. Their three-way collaboration reflected a new approach: not relegating fashion to a specific section of the magazine but allowing fashion, creative and editorial to inform each other, working towards one unified end. The autumn 2015 issue, their first, demonstrated this, featuring Young Thug on the cover, photographed by a then-new art photographer Harley Weir. The rapper was styled by Robbie in a lace shirt from Alessandro Michele’s first Gucci collection, a plastic top by Walter Van Beirondonck and, most famously, a tulle dress by Molly Goddard (which triggered a flurry of news articles).

“We wanted to enter the big league of fashion magazines, but still be the weirdos in the room,” says Isabella. “We felt too young to be there and so pretended to be more grown up than we were.” The magazine, which had by this point dropped the ‘Confused’ from its name, went from a publication that was a music and culture style bible with one devoted fashion issue every year, to a magazine that looked at fashion through the lens of culture and vice versa. It also moved offices, from Old Street to 180 Strand, back into central London where the magazine had first begun. The move was symbolic too, marking Dazed’s transition from a DIY magazine to a more grown-up media group.

However, creativity (and that dynamic chaos that Susie mentioned) remained a part of Isabella, Robbie and Jamie’s era – the magazine had the benefits of independence that comes with being, well, independent, and the team enjoyed and took advantage of that freedom.

“It was about celebrating the community around Dazed,” says Robbie, who now works closely with Craig Green and Simone Rocha, among many other designers and brands. “Part of the DNA of it was supporting and nurturing it, and exposing new talent in fashion, be it photographers or designers. I was interested in this cross-generational thing where you’d be pairing established photographers with up-and-coming designers or stylists or editors. How you could put these two worlds together, people who were high up in the industry and people who were just starting out with a strong collection or a strong idea.”

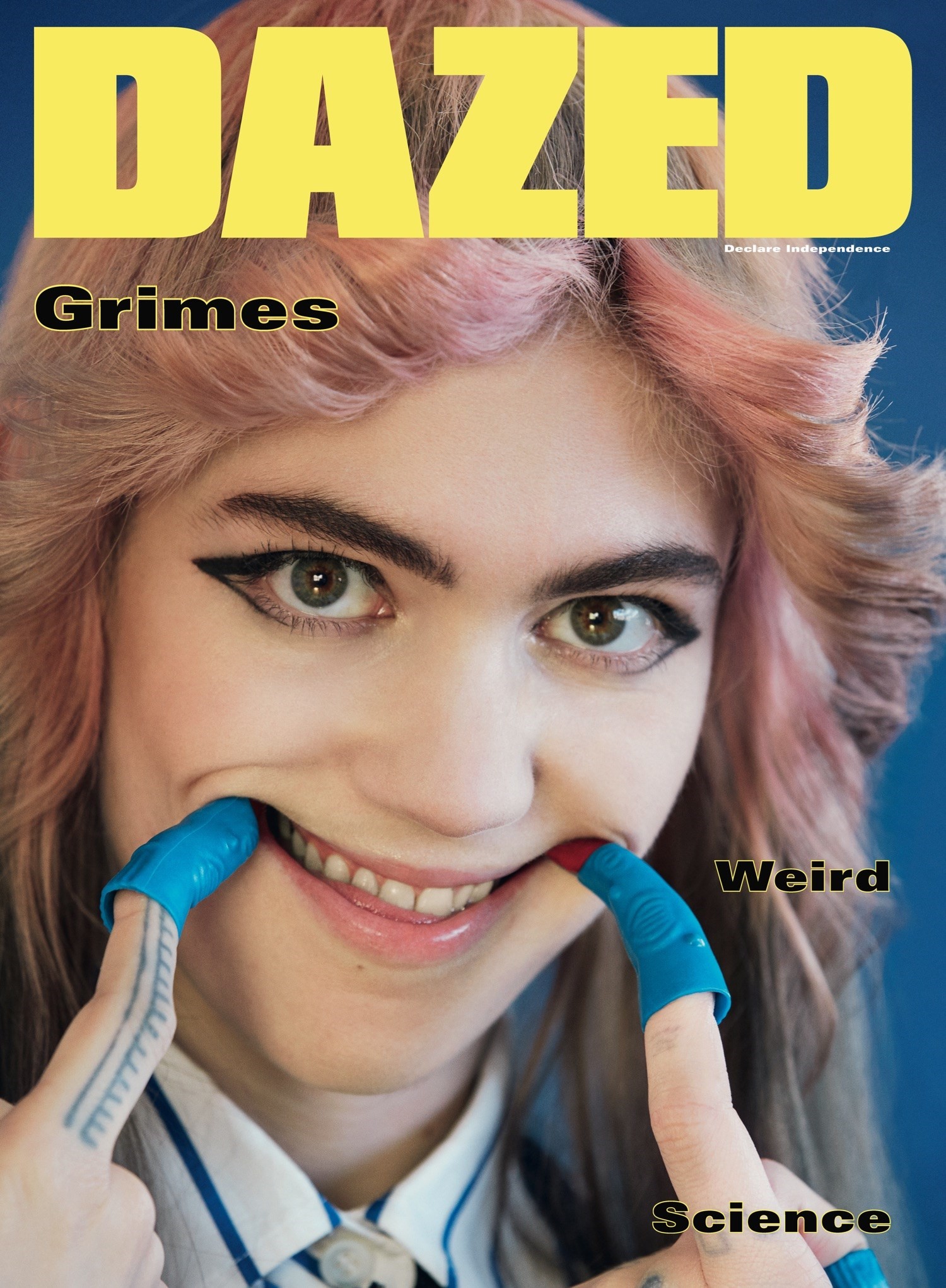

On the one hand they engaged with weighty topics such as trans rights, gun control and cultural appropriation, and orchestrated a Chelsea Manning guest-edit. Young people were becoming more politicised again, and the magazine reflected this. On the other, there was always a sense of rebellious irreverence to these issues: their cover with Grimes saw the musician pulling a distorted smile with her fingers clad in rubber-fingered gloves; another issue featured a Rottingdean Bazaar special starring Charity Shop Sue who, in the accompanying feature by this writer, recounted a story about someone going to the loo in the changing room of her Bulwell-based charity shop, Sec*Hand Chances.

The 2020s

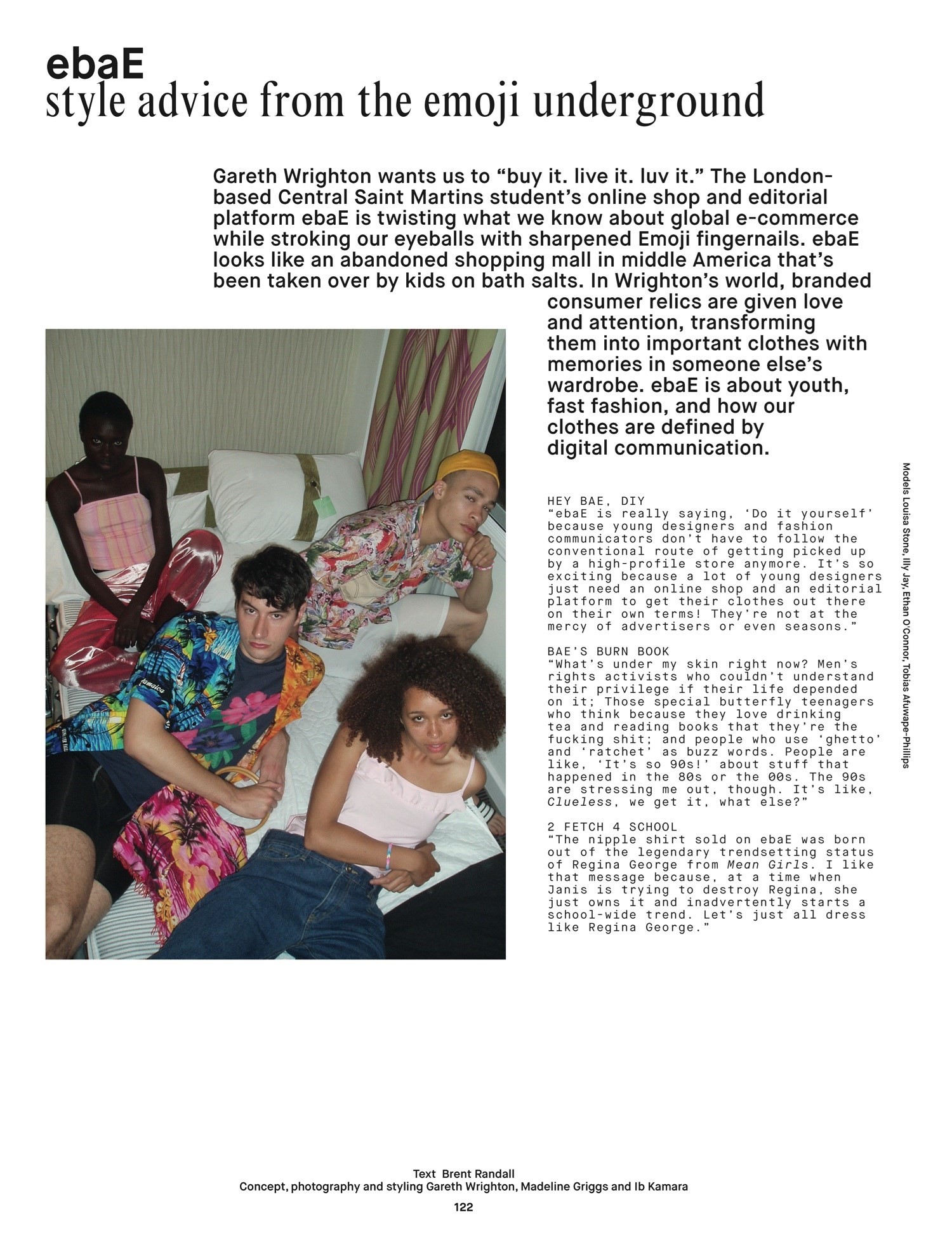

In 2014, Dazed published a story about a project by three Central Saint Martins students. Titled ebaE: style advice from the emoji underground, this project was a satirical kind of online shop and editorial platform – “a fake eBay”, if you will, filled with clothes they’d bought in charity shops and then photographed and styled in a Holiday Inn. “ebaE,” reads the text, “is about youth, fast fashion, and how our clothes are defined by digital communication.” The story’s student creators were Madeline Griggs, IB Kamara and Gareth Wright – the latter two of whom were, six and a half years later, appointed editor-in-chief and art director of the title, respectively.

As well as this, Dazed included IB in the 2017 Dazed 100 and published his first ever fashion story. Part of the winter 2016 issue of Dazed, the shoot was photographed by Jamie Morgan in Paris’s Château Rouge, a predominantly Black area in the city’s 18th arrondissement. Featuring street-cast models, many of whom were African club kids, the story paid homage to IB’s mentor, the late Barry Kamen, and the Buffalo collective to which he belonged. But it was also a foretaste of things to come.

Today, IB acknowledges how his predecessors have laid the foundation for what he’s doing now, and says that he wants Dazed to be even more globally minded. He comes from a different place, both creatively and in terms of his background – IB was born in Sierra Leone and spent much of his childhood in Gambia before moving to London at 16 – and wants the magazine to reflect that. There’s a duality in what he wants to do, too: for while he wants to engage more with what’s going on in the world, he also wants to escape from it. “People want to dream,” he says simply.

While IB and Gareth’s stories are different to many of the others mentioned in this article, in many ways they are similar: Dazed offered them a platform for their work early on in their careers; it then served as something of an incubator or training ground for them; and later became a place where they were given responsibility – and a huge amount of creative autonomy.

“I want Dazed to have a global impact,” IB says today, speaking on what he wants to do with this autonomy. “I want it to challenge and shape culture. I want it to be a creative space for people to be inspired. And I want it to explore what it means to be punk in a time when it’s hard to say anything.”

Dazed: 30 Years Confused is published by Rizzoli, and out on 28 September 2021.