“Sometimes, I feel the past and the future pressing so hard on either side that there’s no room for the present at all,” writes Evelyn Waugh in Brideshead Revisited, the author’s 1945 novel which embedded the bygone era of the British stately home in the public consciousness (the beloved 1981 Jeremy Irons-starring television adaptation ensured ultimate longevity). ‘Brideshead’ has become a byword for the aesthetic extravagances and excesses of the era, tinged with a feeling of romance and decline – the novel ends with the arrival of World War II, an event which pushed past, present and future together so violently as to alter the social strata of Britain forever.

Indeed, “Brideshead” has been used as a description for the work of Steven Stokey-Daley, the Liverpool-born designer who founded his eponymous label SS Daley in 2020; soon after, Harry Styles – who first wore his graduate collection in his Golden music video – was pictured in British Vogue with “his SS Daley pleat-front Brideshead Revisited-inspired dress shirt billowing behind him.” Stokey-Daley’s richly fashioned clothing – vast wide-leg trousers crafted from 19th century British pyjamas, argyle-knit wool vests, shirt pockets tied with bows, straw boaters decorated with sprays of wild flowers – found an overnight global audience, propelling his brand to the forefront of London’s new creative vanguard. Case in point: this past week, two days prior to his second London Fashion Week presentation, he was announced as one of this year’s nominees for the prestigious LVMH Prize.

The merging of past, present and future is an apt descriptor for Stokey-Daley’s own approach, which thus far has centred on an exploration of class – a wryly subversive take on the uniforms and traditions of the British aristocracy in a modern context. His initial collections were formed from watching the students of the historic £14,555 a term Harrow School from afar (the campus of the University of Westminster where he studied is just down the hill from the school’s grounds, its boater hat and blazer-clad students on view from the fashion studio). “There’s these two very disparate places in such close proximity – literally upstairs, downstairs,” Stokey-Daley tells AnOther in the run up to his latest collection. “As I read into it I realised how unbalanced things are – I think it’s like 70 per cent of Britain’s governing body are public or private school-educated, and the percentage of that in the UK as a whole is only around six per cent. I feel like we never really talk about class in the UK. It’s a touchy subject.”

It is an approach which lends Stokey-Daley – who describes his own upbringing in Liverpool’s suburbs as distinctly working class – an outsider’s eye, his collections lingering between the beauty and foreignness of the aristocratic mode of living. “I think on a personal level, I’ve always loved British Roger Hicks interiors, or the Cecil Beaton stately home, it’s just a really beautiful aesthetic,” he says. “But it’s not like I’m celebrating that past, or the elite class, it’s more that I’m investigating them from a point of view of having never seen that stuff before. In London, the more privileged you are, the more you appropriate from working-class culture – so why can’t I do the same?”

Intrinsic to this exploration is a sense of performance – one informed by Stokey-Daley’s own background in theatre, having been part of the National Youth Theatre in London as a teenager (for his first in-person presentation in September last year, the group’s current class performed a specially written piece, inspired by the works of Bertolt Brecht). For him, clothes are embedded with a similar performative quality, constantly marking one’s position in the world; something he sees as a particularly potent expression of class, using the uniforms of Harrow and Eton schools as examples. “In a modern context they are completely outdated – wearing a tailcoat and a top hat to school is completely not of our time. It serves to alienate people that aren’t a part of it, which is all rooted in class divisions. There’s a performative notion to all uniforms, but I set out to question or subvert them, to put them in a different context.”

This past Friday evening at London’s Old Selfridges Hotel, Stokey-Daley initiated a new chapter of his label with an Autumn/Winter 2022 show which left public school behind but nonetheless remained rooted in an exploration of the British class system, a play on the “upstairs, downstairs” trope of servants and masters common in literature and film. Stokey-Daley had watched Robert Altman’s Gosford Park – written by Julian Fellowes, the stately home-set murder mystery was a precursor to his later Downton Abbey TV series – and begun to collate a moodboard of references, which included Chatsworth House, the ancestral home of the Duke and Duchess of Devonshire, Tatton Park, a neoclassical estate in Knutsford he had visited in primary school, and a photograph of Diana, Princess of Wales in a coat from the 1980s which he had been waiting to use for several seasons.

“I wanted to have that same commentary about social class, but I felt like what I had done about public school was wrapped in a bow – the last collection finished with a black silk tailcoat, like the boy was graduating,” he says. “This collection was about putting that same conversation in a different context. If you look at what’s going on today – when you think about the government, and the whole party-gate scandal – it feels like the rich can have their cake and eat it, and drink wine, and everyone else is excluded from the party. It just felt more relevant than ever to have that one world for the upstairs, and one world for the downstairs.”

“The more privileged you are, the more you appropriate from working-class culture – so why can’t I do the same?” - Steven Stokey-Daley

So in the vast concrete space, Stokey-Daley conjured his own stately home via a series of milieus – a chaise longue, a picnic, a four-poster bed, a dining table, each surrounded by a dishevelled gathering of flowers, stacks of books, old photographs, blankets and paintings. As the show began, the scenes were populated by dancers, a sinuous, shifting series of coupling and groups in various states of embrace – Stokey-Daley said he was interesting in “queering” the British stately home, imagining two men running into each other’s bedrooms after a lavish cocktail party. “I was thinking of these two guys, who were really into each other, but couldn’t express that because they are suppressed,” he says. “And what would they look like?”

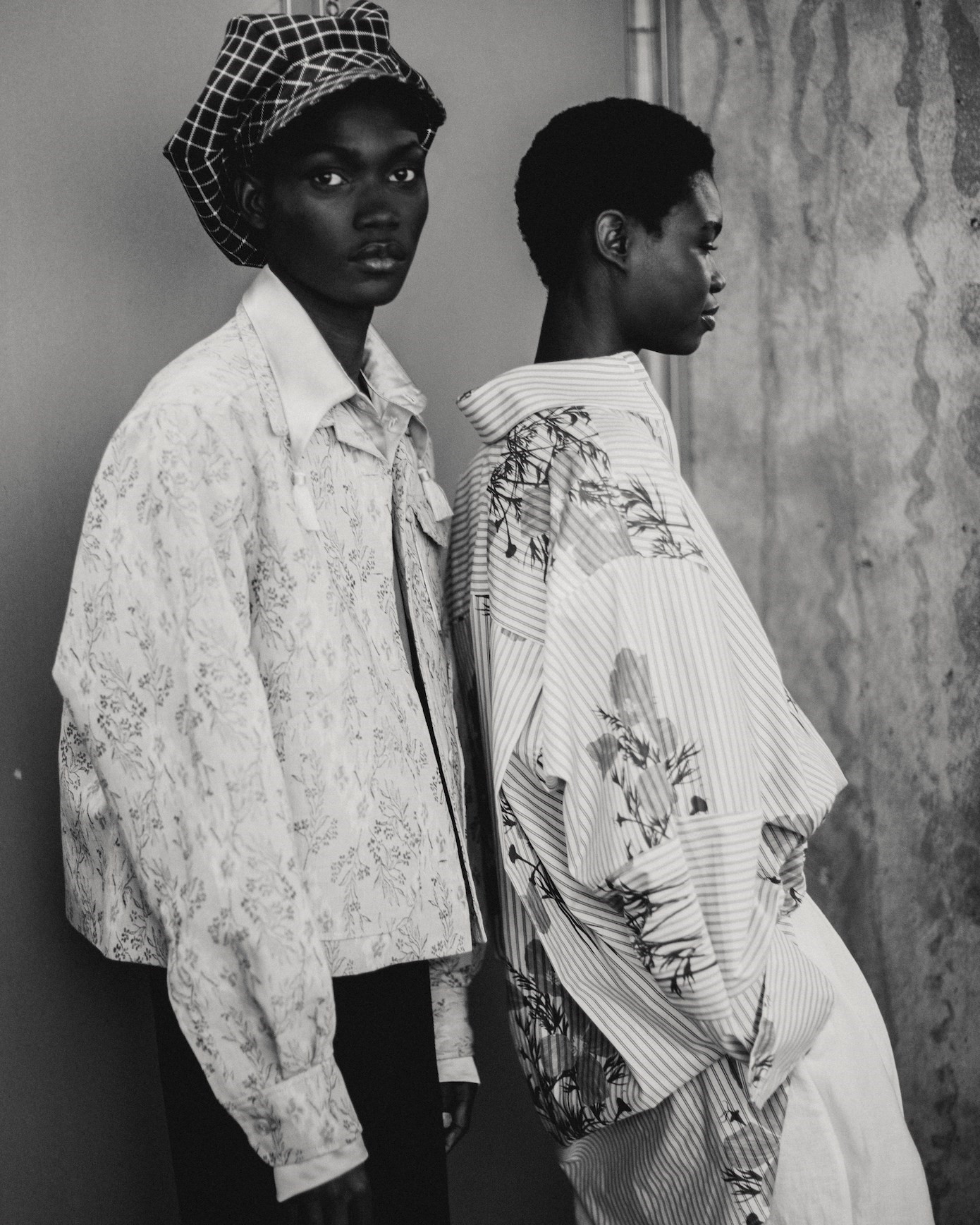

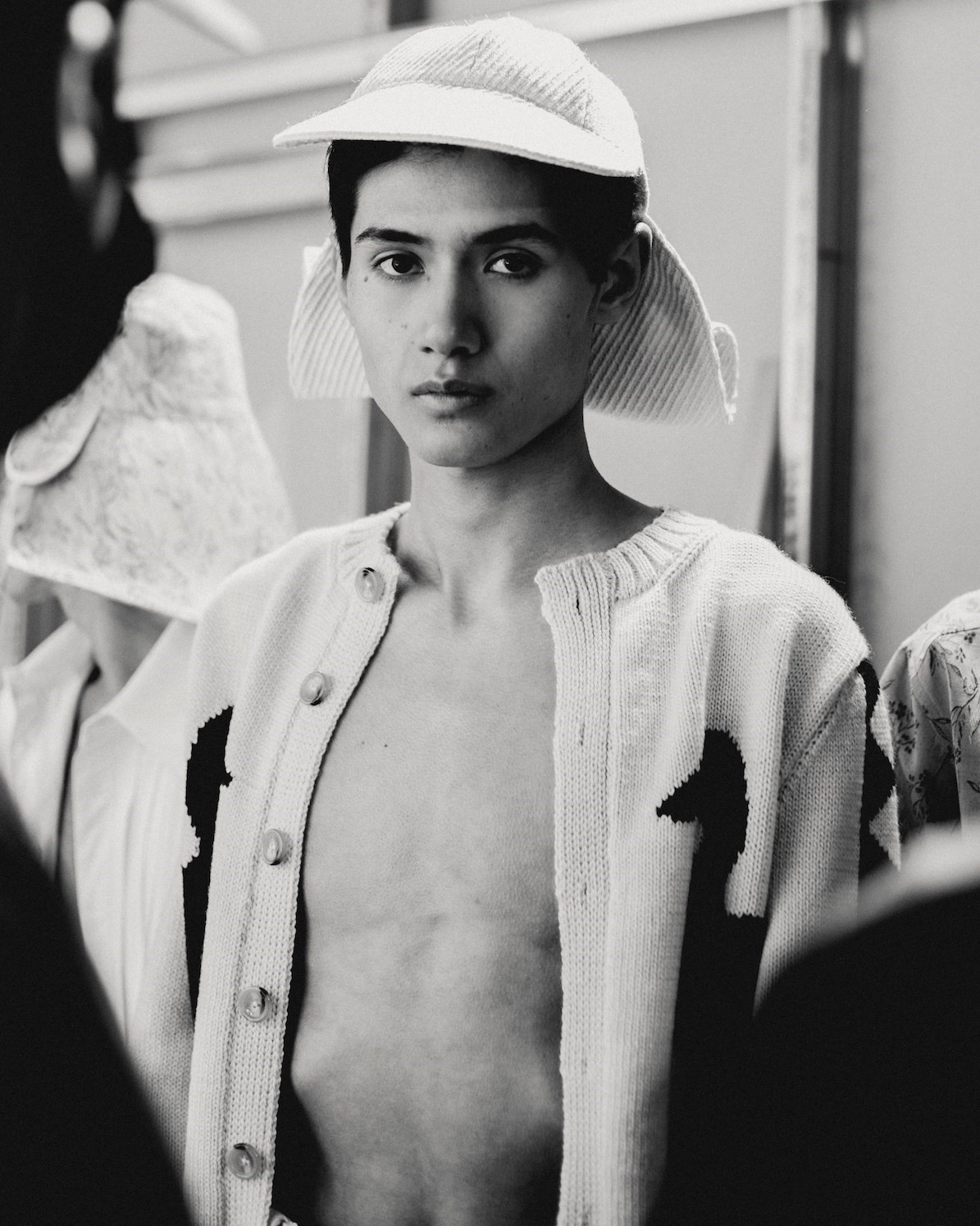

It led to a “sexier” collection, a debauched undoing of a weekend in the country, opening with what Stokey-Daley called one of the collection’s defining looks – a waistcoat, cut from triangles of leather, nothing beneath but a pair of SS Daley-branded underpants, suspender socks and leather loafers. “For me there’s nothing sexier than just a flowing white shirt on a guy,” he says. Elsewhere, Stokey-Daley offered a darker take on his usual brand of whimsy – his supersize trousers came this season in rich black satin, underwear-inspired vests with peepholes, tied seductively at the back, while spliced pinstriped tailoring with cut-up illustrations of birds and flowers. The references came from a melange of eras – pieces could come from the 1880s or 1920s, or indeed the present day – which the designer says is intentional, a way of working which allows him to look back at history without verging on costume.

“You get tied into rules and rigidity when you reference something historical, and I had to overcome that,” he says. “It’s about approaching things loosely; I just told myself to be way more free with the references. That’s why it feels cross-generational. Somebody described my clothes in a great way: the stuff you wished you could find in vintage shops. It’s that nod to the past, but aware of the now.”

Of his own personal history, Stokey-Daley admits that he wasn’t really interested in fashion growing up – he wasn’t a teenager who would flick through the pages of Vogue, or spend his time watching old runway shows on YouTube. “I never had that relationship with fashion where I romanticised it from a young age, clothes were never really something that we celebrated as a family,” he says. Even when it was time to go to university, he originally planned to study English Literature and Theatre Studies at Warwick – the car was packed and ready – before a split-second decision saw him shift to the art foundation course needed to go on to undertake a degree in fashion. He says he’s still not entirely sure of the reason why.

Part of it, he thinks, might be down to his grandmother, who worked in a clothing factory close to where he grew up. “She told me that she was offered an apprenticeship with a tailor if she moved out, but at that time girls were just persuaded to get married and have kids,” he says. “She always looks back on that and thinks: ‘what if I did that? What if I didn’t settle down at 20 years of age and have children?’ From that, there’s always been this narrative of ‘what if I got out of this place and did something else?’”

“It set me up to think that way as well. It doesn’t mean that I don’t like the place I’ve come from, it just means I’m on that same journey: what if I don’t live this life, and try to do a different thing? It’s why my comment back to the people who ask why I make clothes based on the upper classes is, ‘Would you rather me stay in my box, stay in my lane, and make tracksuits?”’