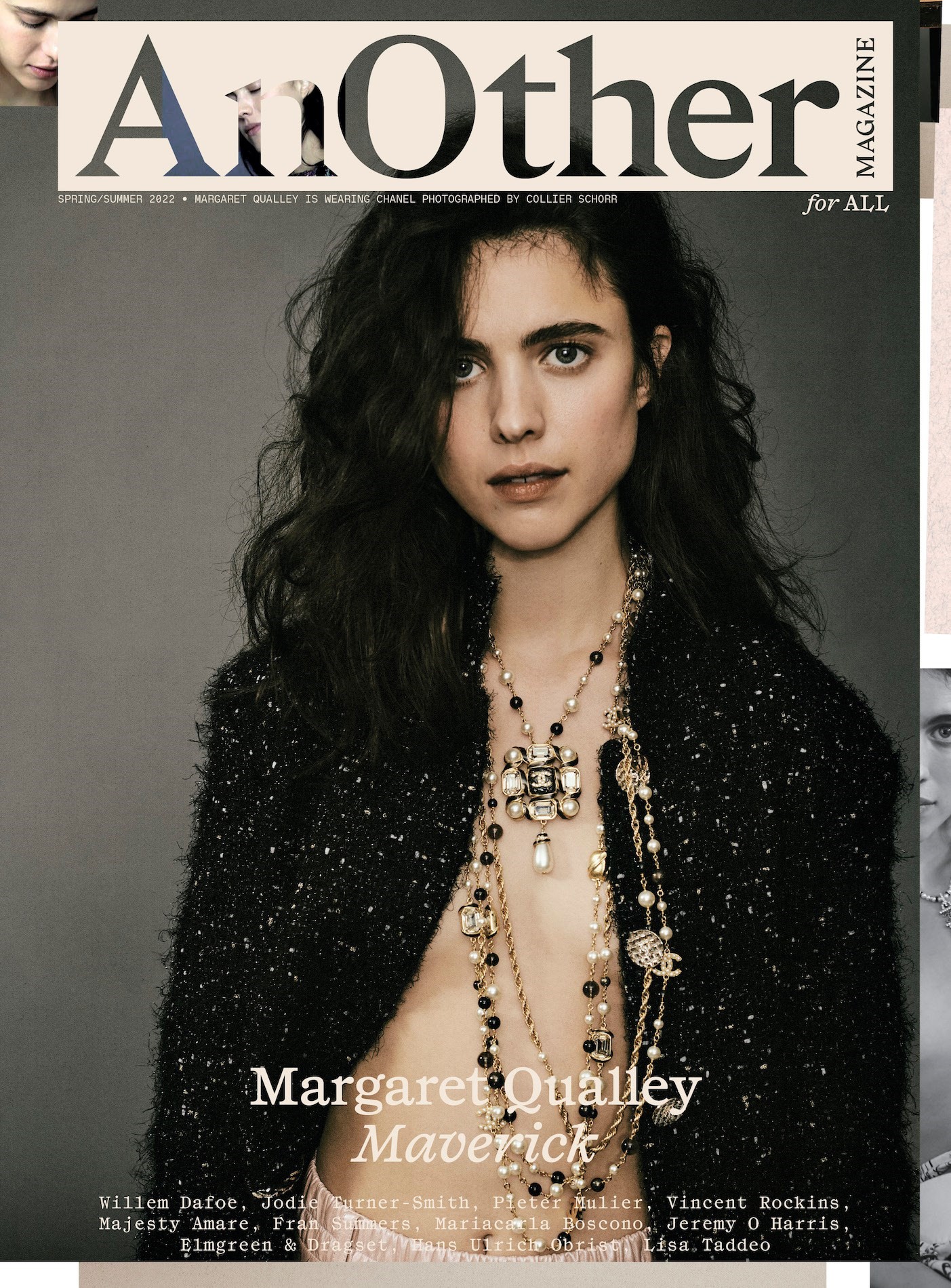

This article is taken from the Spring/Summer 2022 issue of AnOther Magazine:

Margaret Qualley is learning how to trust herself. It doesn’t always come easily to the actor. In 2018, Qualley was on the biggest production of her life, Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time ... in Hollywood. It was only a minor role: that of Pussycat, a fictionalised member of Charles Manson’s cult, the Family. But a Tarantino film. Qualley had never dreamed she’d be asked to be in anything so prestigious, or share screen time with Brad Pitt. (“He’s all the things you want him to be,” she says.)

It was the first day of filming at a ranch in the Simi Valley, a stand-in for Spahn Ranch, where Manson infamously devised the gruesome Tate-LaBianca murders that, as Joan Didion famously wrote in The White Album, brought an end to the Sixties. Dogs prowled the perimeter: Tarantino was insistent they be visible in every shot, to approximate the rangy, pseudo-beatnik vibe of life in a cult. The then 23-year-old Qualley was nervous, of course, and focused on getting through the scene without flubbing her lines in front of her co-star Pitt, who was playing languorous stuntman Cliff Booth.

But Qualley had this urge. Pussycat is a louche, free-loving, hitch-hiking hippy chick with LSD-dipped cigarettes in her back pocket. She does what she wants and thinks social norms are a drag. She’s all uncontrolled id in denim cut-offs and a halter top. Pussycat would do something off-key in this situation, Qualley just knew it. Like? Stick her tongue out at Cliff. A half-leering, half-promiscuous gesture. Jarring, but also an invitation.

Qualley thought about it but ruled it out. “I thought, I better not do that,” she recalls. “Who am I to take up that space? This is my first day on the job, this is Brad Pitt and Tarantino. What the fuck am I doing? I better just obey.”

Afterwards Tarantino beckoned her over. He asked Qualley: was there something you wanted to do in that scene that you didn’t do? “How did he fucking know that?” Qualley wonders. “I was blown away.” And with that, Tarantino gave Qualley permission to lean into the sheer weirdness of her role. She did indeed loll her tongue at Pitt in the next take, and it became one of the stand-out moments of a stand-out film, earning Qualley rave reviews for what might have been, in the hands of another actor, a blink-and-you’ll-miss-it role.

“You forget that you’re supposed to be messy,” she says. “You’re supposed to take up all the space and make all the mistakes, and you’re supposed to do the thing you feel. But it’s so scary sometimes.”

“The messier you are, the more mistakes you make, the more vulnerable you are, the better it is” – Margaret Qualley

She was born in Montana to the actor and model Andie MacDowell and the model-turned-property contractor Paul Qualley. Her parents divorced amicably when she was five and moved to Asheville, North Carolina, where Qualley and her siblings Rainey and Justin split their time between their parents’ houses. Growing up in a small town had its blessings – Qualley was removed from the neuroses and competitiveness of the LA scene – but also downsides. “My mom was the only actor in Asheville,” Qualley says, “so it makes you a bit more on display, and people are interested when there’s nothing really interesting going on.”

Qualley was a strange, terminally uncool child. She would think that inanimate objects like pillows and chairs had feelings and was obsessed with making sure that her socks were neat and unwrinkled. Later she grew into what we would now call a social justice warrior, only this was in the early Noughties, when activism was uncool. “I was a vegetarian who was selling recycled global-warming bracelets for charity and sifting through the trash bins, being like, ‘You didn’t recycle this,’ and putting up pictures of cows being slaughtered,” she laughs. “I was so annoying, and passionate, and gangly.” By contrast her sister was “conventionally beautiful in her own whimsical and incredible way. I grew up in a time when it was, like, Uggs and Juicy Couture, and denim miniskirts, blonde hair and boobs. And I was like” – Qualley gurns and affects a deep voice – “look how long my fingers are.”

Even if it’s difficult to accept for a moment that anyone could ever see Qualley as an ugly sister – she is possessed of the sort of luminous beauty that has booked her Chanel and Kenzo campaigns – she is such a funny and self-deprecating raconteur that it’s possible to suspend disbelief. Sprawled across a sofa in her New York City apartment, Qualley is dressed casually in a T-shirt, her hair pulled back in a French plait. She’s in high spirits despite the fact that she’s got a nasty-looking infection in her right eye. “Don’t mind my eye!” she hoots, leaning into the camera so I can get a closer look. “I have this crazy thing going on. Or do mind it. It’s been a process.”

Although Qualley would visit her mother on set, once spending a memorable few months running free on an Italian island, she had no interest back then in pursuing an acting career. Dance was her first love. “I did competition dancing and ridiculous Honey Boo Boo pageant-style dancing,” she says. Alas, there are no pictures of this online. “And then at a certain point I realised that ballet was more sophisticated and the pinnacle of perfection. So I was like, OK, I should do that.” Qualley studied dance at the prestigious North Carolina School of the Arts. “The obsession,” she says, “really was about being perfect.”

Aged 16, after attending a summer programme held by the American Ballet Theatre in New York, Qualley had a dark night of the soul. “I realised,” she says, “you don’t even love this. You’re just doing this because you want to be perfect, and you’re about to waste your whole life because you’ll never be perfect.” She wrote her parents a long, impassioned email, outlining her plans to become self-sufficient, and persuaded them to let her stay in New York, where she became a working model. In her telling of the story, Qualley is a hillbilly doofus who avoided getting into elevators with men because someone had told her that men attack women in New York City lifts. “I was like,” she snorts, “is this guy going to kill me? I better leave.” Qualley was likely more sophisticated than she lets on – she was, after all, presented to society at Le Bal des débutantes at the Hôtel de Crillon in Paris later that year.

But the New York modelling scene is not a healthy place for a perfectionist teenager and Qualley has spoken elsewhere about developing an eating disorder. “I was really hard on myself when I was in high school and modelling, and just trying hard to be perfect at everything, and be a perfect student, and a perfect model,” she says. This was a pre-body-positivity time, when high-fashion models were uniformly size zero. “Hopefully now there’s more body inclusivity,” she says, “and celebrating all of the different variations of bodies, and how beautiful that is, and how versatile beauty is in general. It’s wild that we shift through people with the same criteria in mind, that people have checklists. I’ve been a victim of that, and it’s a dark, ugly place to exist.”

“For young women ... we’re often told that our accounts of reality aren’t correct. That the way you feel and the way you’re experiencing the world is somehow your fault” – Margaret Qualley

Qualley freely admits that her mother’s celebrity created a carapace around her. “I think I’ve been protected in a certain way my entire life because of that. I was put into a different category and there’s definitely a protective shield that I feel is related to being my mother’s daughter,” she says.

Qualley quit modelling after four months. “I realised it wasn’t good for me,” she explains. Her boyfriend at the time, The Fault in Our Stars actor Nat Wolff, took her to an acting class in a church on the Upper East Side. For the repressed, hard-on-herself Qualley, it was a revelation. “The thing that I loved,” she says, “was that back then I didn’t give myself permission to have many feelings in life. I was an incredibly disciplined, controlled person, that didn’t talk very much, and nodded a lot, and never broke the rules. So I didn’t have permission to do anything or have any feelings, basically. And then I went to an acting class and I got really mad, got really sad and had all the feelings. And I was like, ‘This is great! I could try to get paid to do this – that would be nuts.’ And I still feel that way.”

After so many years of ballet and modelling – both professions that demand punishing self-discipline and a certain degree of stoic professionalism – acting felt loose, chaotic, exciting. Like throwing paint at a canvas, Jackson Pollock-style, instead of the technical precision of the old masters. Like peeling off Spandex and pulling on sweats. Like being given permission to be the goofy, oddball version of herself that she was when she was a climate-change evangelising little girl instead of the uptight model. But with liberation comes a different sort of fear.

“What I love about acting,” Qualley says, “is that it’s so scary to do it. It’s a real fear-factor kind of thing, in the sense that the messier you are, the more mistakes you make, the more vulnerable you are, the better it is. You’re constantly in front of the camera, going, ‘I’m not perfect, I’m not perfect, look at me, I’m not perfect.’ And that is terrifying, but incredibly exhilarating. And coming to terms with that is going to be something I work on, I think, for ever.”

In less than a decade Qualley has become one of Hollywood’s brightest talents, even if she doesn’t actually live in the epicentre of the movie industry. “New York feels very cosy to me,” she says. “LA feels scary. LA feels like I’ll never be good enough.”

She is at her happiest when she’s walking around New York, eating cereal milk ice cream from cult favourite Milk Bar. “It’s a touristy thing,” she says, “but I think it’s just phenomenal.” For many years Qualley’s apartment didn’t have any furniture: she ate meals from a plate on the floor. “I have furniture now,” she deadpans, gesturing proudly. “It’s really exciting.” In New York you can throw a dime in most directions and hit a celebrity. “Nobody gives a shit,” Qualley says. She prefers the relative anonymity of big-city life. “No one stops me,” she insists. “I really am not terribly recognised. And any recognition I get from my work is great because I want to touch people. I’m telling these stories because I want them to be watched.”

“A lot of actors – and people – are people-pleasers. Who doesn’t want love? And it seems like the easiest way to get it” – Margaret Qualley

In 2021, Qualley got her wish, starring in the Netflix smash hit miniseries Maid, based on Stephanie Land’s 2019 memoir of her time spent working as a cleaner to support her infant daughter after the break-up of an abusive relationship. Maid is an unflinching portrayal of abuse, poverty and the backbreaking reality of life for low-income Americans, but it is also a show about maternal love, the dignity of work and finding joy in small things, whether a walk through sun-dappled forests or singing along to a favourite Salt-N-Pepa song in the car. Shoop shoop ba-doop.

As Alex, Qualley is straight-backed and utterly without self-pity, even as life heaps calamities upon her: a car crash, homelessness, employers who stiff her out of her wages. The role was a revelation. “So many people are just treading water to get by,” she says, “just barely able to pay their bills and stuck in this constant loop of trying to stay afloat. To be a person in the States who is lower middle class and working your fucking ass off, and still be a good mom or a good dad, I think is truly heroic. It’s just fucked up what we do to people.”

Her on-screen relationship with daughter Maddy, played by five-year-old Rylea Nevaeh Whittet, is the emotional heart of the show. “I became obsessed with hanging out with Rylea,” Qualley says, “because the hardest challenge was to make a convincing mother-daughter relationship. I’m not a mom and it’s a really challenging feat to be a believable mother to a child I don’t know, and who doesn’t know me, more importantly. So I just spent all of my time with her and carried her around everywhere, and temporarily kidnapped her from her parents.” They would go grocery shopping and make pancakes. At the end of many scenes where she was carrying her in her arms, Qualley wouldn’t be able to tell if Whittet was pretending to be asleep or was actually so relaxed she had nodded off.

Her hard work paid off: Qualley and Whittet’s relationship is as plausible and nuanced as is possible to imagine, as is the on-screen relationship with Alex’s mother Paula – which is unsurprising, given that the role is played by none other than MacDowell. Qualley lobbied for her mother to have the role, calling Margot Robbie, one of Maid’s producers, who loved the idea. “It was the biggest cheat I’ve ever managed to pull off,” Qualley said last year, pointing out that the comfort of having her mother on set gave a sense of easy confidence.

Maid is not only critically acclaimed but has also advanced the public understanding of emotional and financial abuse. “One of the greatest things about Maid was how accessible it was,” says Qualley. “How so many people felt a part of their story was being told. They saw themselves there, or their sisters there, or their moms.”

While Qualley credits her time on Maid as one of the most fulfilling professional experiences of her life and is full of praise for everyone involved in the production, she had to stand her ground when it came to her vision of Alex. “Everyone was really disappointed in me at first,” Qualley says, “because they thought I couldn’t access rage, and that I was playing a victim, essentially. And I was like, ‘No, I can access rage, I promise you.’” Qualley explained that Alex simply wouldn’t lose her cool while holding Maddy in her arms. “Alex is fucking smart and she’s not going to blow up at someone unless it’s going to have an effect. If she’s holding her child, she’s going to be mindful of her child’s experience. She’s a mama bear. She’s going to protect her kid at all costs.”

“I’m working on trying to get back to whatever I was when I was a little kid, which is a total freak show” – Margaret Qualley

It wasn’t until they came to film episode three, where Alex confronts her ex-boyfriend Sean in a bar, that she was proved right. “I yelled like crazy and they’re like, ‘Finally,’” Qualley says. “I was like, ‘Well, yeah, no shit. I’m not holding a kid and this is something that I’m mad about.’” It may not seem like much – a creative disagreement that was resolved to the satisfaction of all parties involved – but for an inveterate people-pleaser it was progress. No Tarantino standing in the wings, mouthing “OK” at her. Qualley understood the role on an elemental level and was ultimately vindicated.

“For young women,” Qualley says, “we’re often told that our accounts of reality aren’t correct. That the way you feel and the way you’re experiencing the world is somehow your fault, and if you want certain things you should feel bad for wanting those things.” We’re not talking about Alex, or Maddy, or Maid any more. Something bigger. “By proxy of standing up for Alex and standing up for Maddy,” she continues, “I was able to realise that I shouldn’t feel ashamed of certain wants or beliefs or feelings. And that it is literally still hard to say these things, because people are so conditioned and practised not to speak this way.”

I ask her whether she still feels like a people-pleaser. “Definitely,” she responds. “A lot of actors – and people – are people-pleasers. Who doesn’t want love? And it seems like the easiest way to get it. I don’t know if it’s the right way to get it, but it seems to make sense. If I make this person happy, maybe they’ll stick around; maybe they’ll love me and love feels great.” Qualley drew on these experiences of desperate longing when playing the iconic choreographer and dancer Ann Reinking in the 2019 miniseries Fosse/Verdon, a role for which she was Emmy nominated.

Reinking was the partner of legendary Cabaret choreographer and director Bob Fosse after his split from the equally legendary film and Broadway star Gwen Verdon. There were three people in their relationship – Fosse and Verdon continued to work together, even after their romantic partnership ended – and Reinking fought valiantly to get Fosse off drugs and booze, to little effect. “I see a similarity in us,” Qualley says, “which I’m hesitant to say, because I really do look up to her. The similarity I see is like, ‘Let me lay down so you don’t have to push me down. It’s safer to just be run over by the bus of my own choosing.’”

Qualley got to know Reinking before she died in 2020. “She was the most giving, generous, humble, kind, sweet, powerful thing. All she did was just love everybody all of the time,” Qualley says. “You’d ask her about somebody and she’d go, ‘Oh, they’re the greatest.’” Getting to know Reinking made Qualley reflect on her own approach to relationships. “I’ve been trying to think lately,” Qualley says, “what allows certain people to not hurt themselves by letting people walk over them, but to take a bullet instead of being resentful and angry and hung up on it. I think that ability to love other people in such a big way comes from loving yourself in a big way. So I’m working on that.”

Has she been walked over or treated badly in the past? “Yeah,” she says. “And I’m really lucky now because I have really amazing people that have the best intentions. I’m really lucky. I’m not getting hurt very much. But you’re not always going to be around those safe, special people. You have to build up those skills and figure out how to navigate the world.”

“You’re not always going to be around those safe, special people. You have to build up those skills and figure out how to navigate the world” – Margaret Qualley

In January 2021, Qualley was reported to have ended her relationship with fellow actor Shia LaBeouf after his ex, musician FKA twigs, filed a lawsuit against him, alleging sexual battery, assault and intentional infliction of emotional distress. (LaBeouf has denied some of the allegations made by twigs and other former girlfriends but accepted accountability for “those things I have done”.) Qualley has not commented publicly on their break-up but signalled her support for twigs in an Instagram post, in which she shared a picture of a magazine cover the singer had recently shot, accompanying it with a caption that read, simply, “Thank you.”

Now Qualley is happily in love, although she doesn’t say with whom (according to gossip blogs it’s musician, songwriter and frequent Taylor Swift collaboator Jack Antonoff). She met his parents a few months ago. “Terrifying,” she says. “Please like me, please like me, this is so important, please.” I ask how it went and she grins. “Great,” she says. “Love them.”

Lately Qualley has been surprised by how fast she’s changing. Maid was a nine-month shoot, and in that time “I changed so much,” she says. “I grew a lot in that time, or shed a lot, whatever it is.”

Her goal right now, she says, “is to be like I was when I was a kid. We come into this world and we’re just the purest versions of ourselves. And then we put on all these affectations and people-please. We go to middle school and we’re like, ‘I want the boys to like me, and the girls to like me,’ and so you’re taken away from yourself a bit. You’re putting on all these different shields. I’m working on trying to get back to whatever I was when I was a little kid, which is a total freak show.”

What Qualley might term a “freak show” other people would probably see as incredibly charming. She has a goofy quality to her personality that comes out in compulsive self-deprecation, silly voices and a dork laugh that sounds like it’s running away from her in fits and starts. When I ask her what her best quality is, she groans, before finally offering that she makes a good breakfast and is “clean”. Despite her lifelong proximity to fame, Qualley is unaffected and down to earth, her happiest when she’s improvising a dance routine in a hotel corridor or eating her dad’s favourite pancakes. When not filming, she’s been spending her time at his latest construction project, a block of flats he built himself on the windswept beach of San Carlos, on Panama’s Pacific coast.

But her opportunities for downtime are limited. She recently wrapped production on the Claire Denis film The Stars at Noon, based on a 1986 novel by Denis Johnson about an American woman caught up in the Nicaraguan Revolution in 1984. Filming took place in Panama, which meant that Qualley’s father was able to stay with her and visit her on set. “My God,” she exclaims. “It was so freaking cool!” Because of the pandemic she hadn’t seen him for nearly two years. He went to see her every day, listed on the call sheet as “Margaret’s dad”. They would go for long walks in the morning before filming. She jokes that she was able to finally take him back with her to the US when filming wrapped. “It’s good because he can get all the surgeries that he needs,” she says. (Building all his construction projects himself, without external help, means Paul can be accident-prone. Qualley credits him with teaching her her work ethic.)

“I think playing the dark sad girl is my go-to, but it’s not on purpose. People just think I’m that. I can play convincing dark sad girls. But I’m not really that sad, and I don’t think I’m dark” – Margaret Qualley

In addition to The Stars at Noon, Qualley has a part in Yorgos Lanthimos’s upcoming Poor Things, alongside Willem Dafoe. “Margaret made me laugh a lot and was always game and unpretentious,” says Dafoe of their time on set. The feeling is mutual. “He is so grounded and great and giving and kind and professional,” she says. “And he’s always telling the most ridiculous stories that are just normal anecdotes for him.”

If the past decade has been a whirlwind, there are some moments that stand out. Like driving down Sunset Boulevard shortly before the release of Once Upon a Time ... in Hollywood and seeing herself on a billboard for the movie. Qualley hadn’t told anyone about the role because she was convinced she would be cut out in the edit. “I was like, ‘I guess I’m in the fucking movie,’” she remembers. “It was shocking.”

She’s determined to maintain that wide-eyed sense of gratitude and joy about a job that brings her transformation and release. “I want to keep pushing myself,” she says, “and I want to keep having fun and keep doing things that are important to me. I don’t know what that will look like. I feel like I’m so different from last month to this month, and who knows where I’m going to get to next month?” Qualley knows what she doesn’t want to do: be typecast as a loose approximation of her character in Maid. “I think playing the dark sad girl is my go-to,” she says, “but it’s not on purpose. People just think I’m that. I can play convincing dark sad girls. But I’m not really that sad, and I don’t think I’m dark.”

More than anything, Qualley wants to stay true to herself: to the “total freak show” she was before she grew up into a person anxious to please others, at her own expense. To be maverick. To be authentic. “I want to make sure that my intention when I’m making something is never to please the cool people,” she concludes. “You know what I mean? I want to operate from that place.”

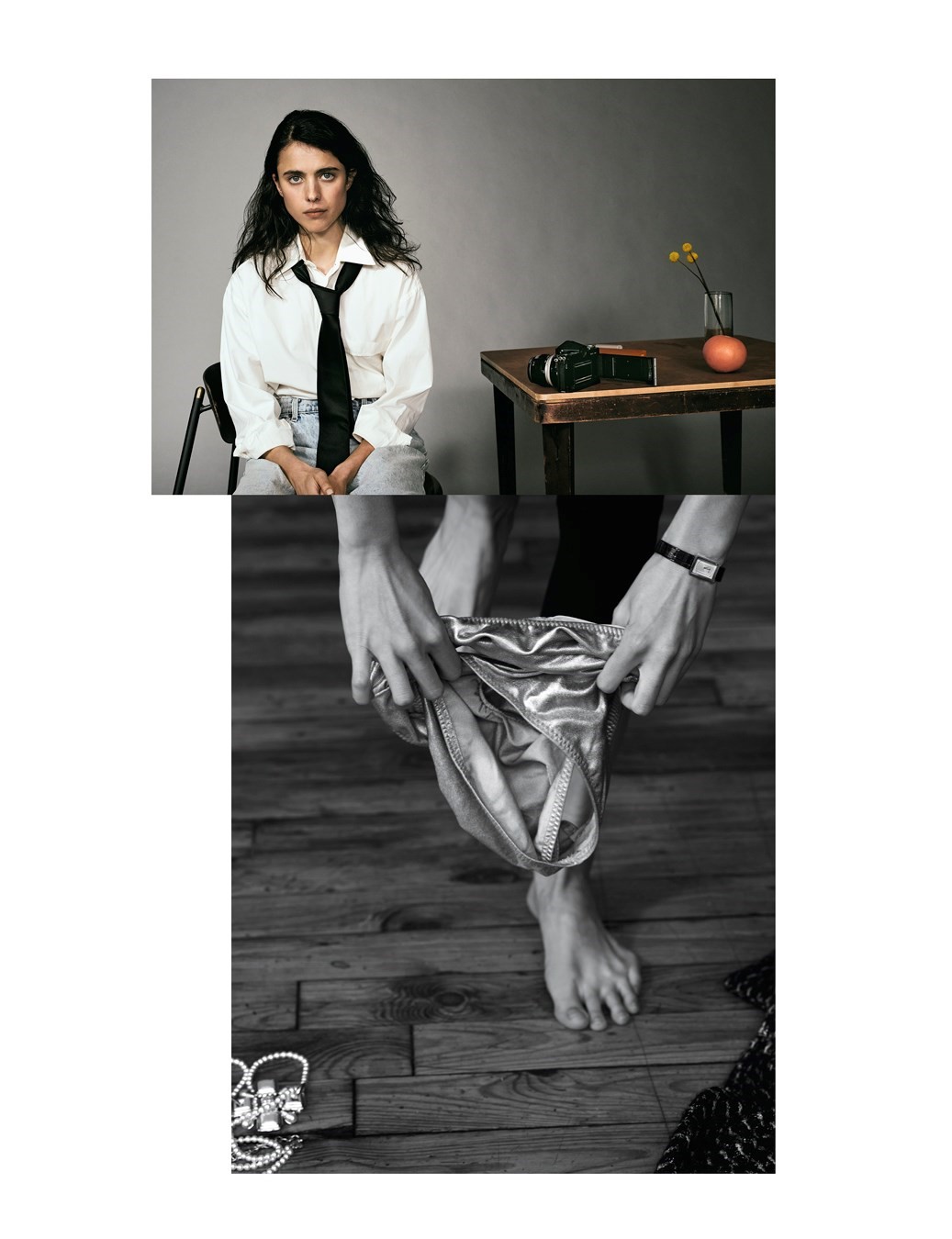

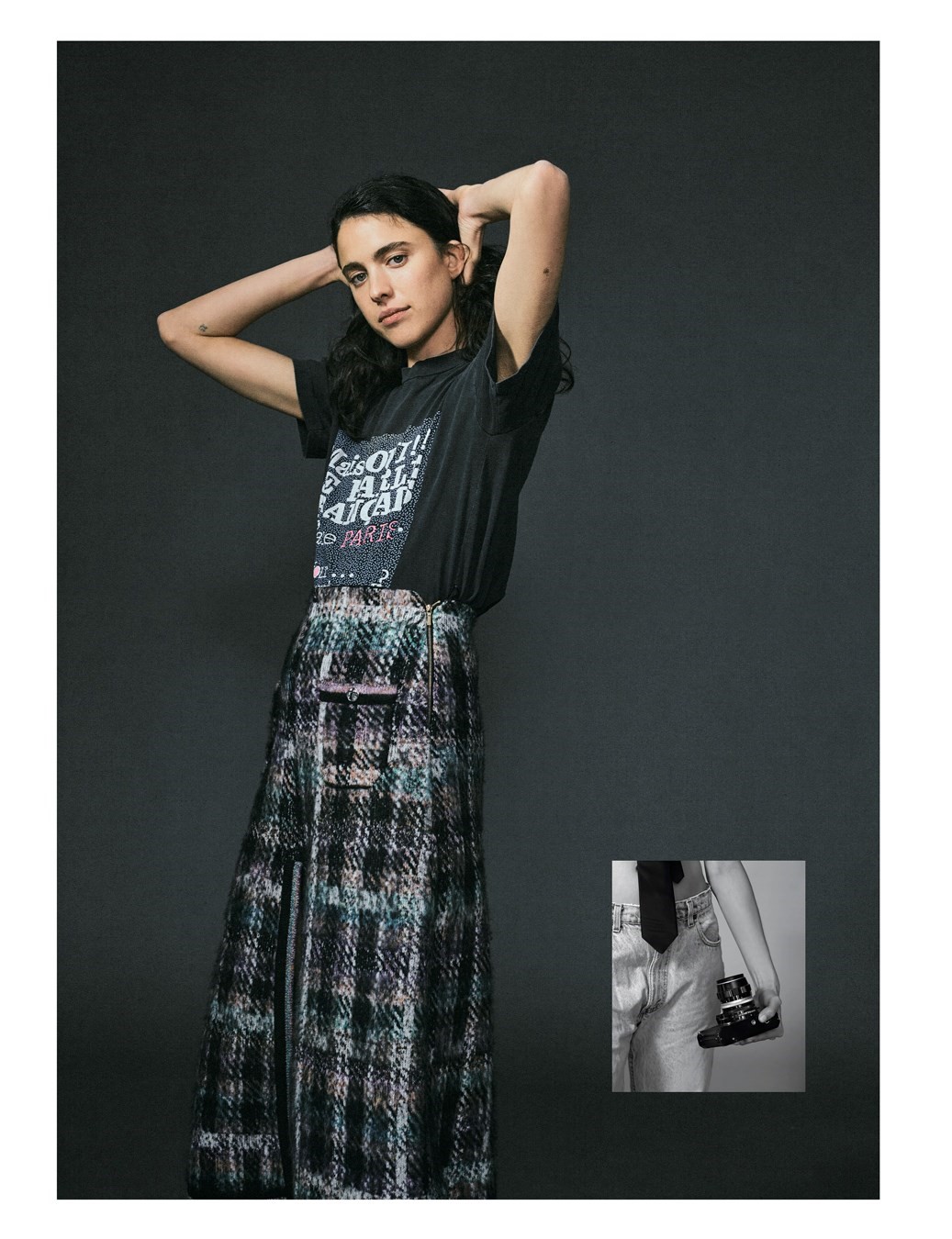

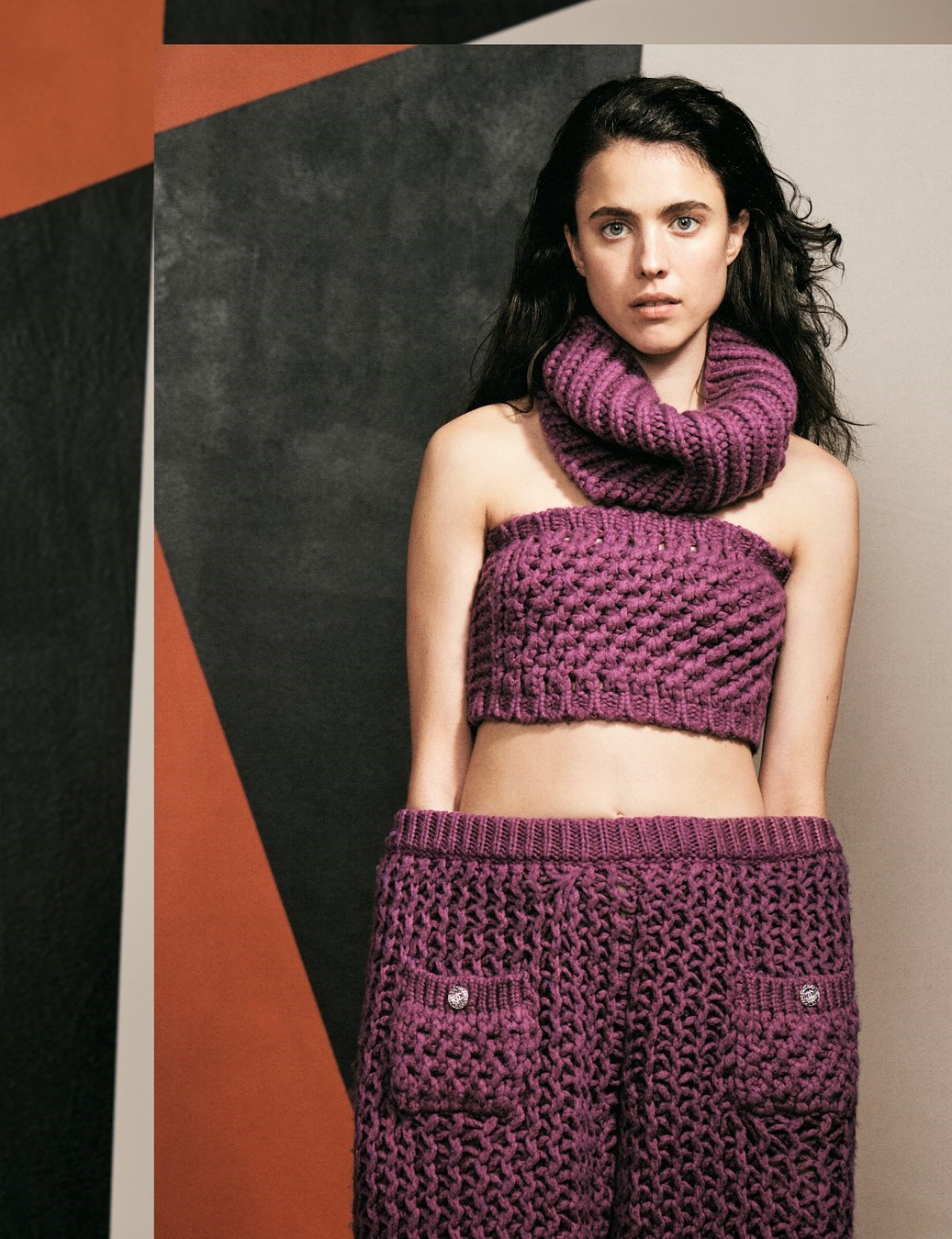

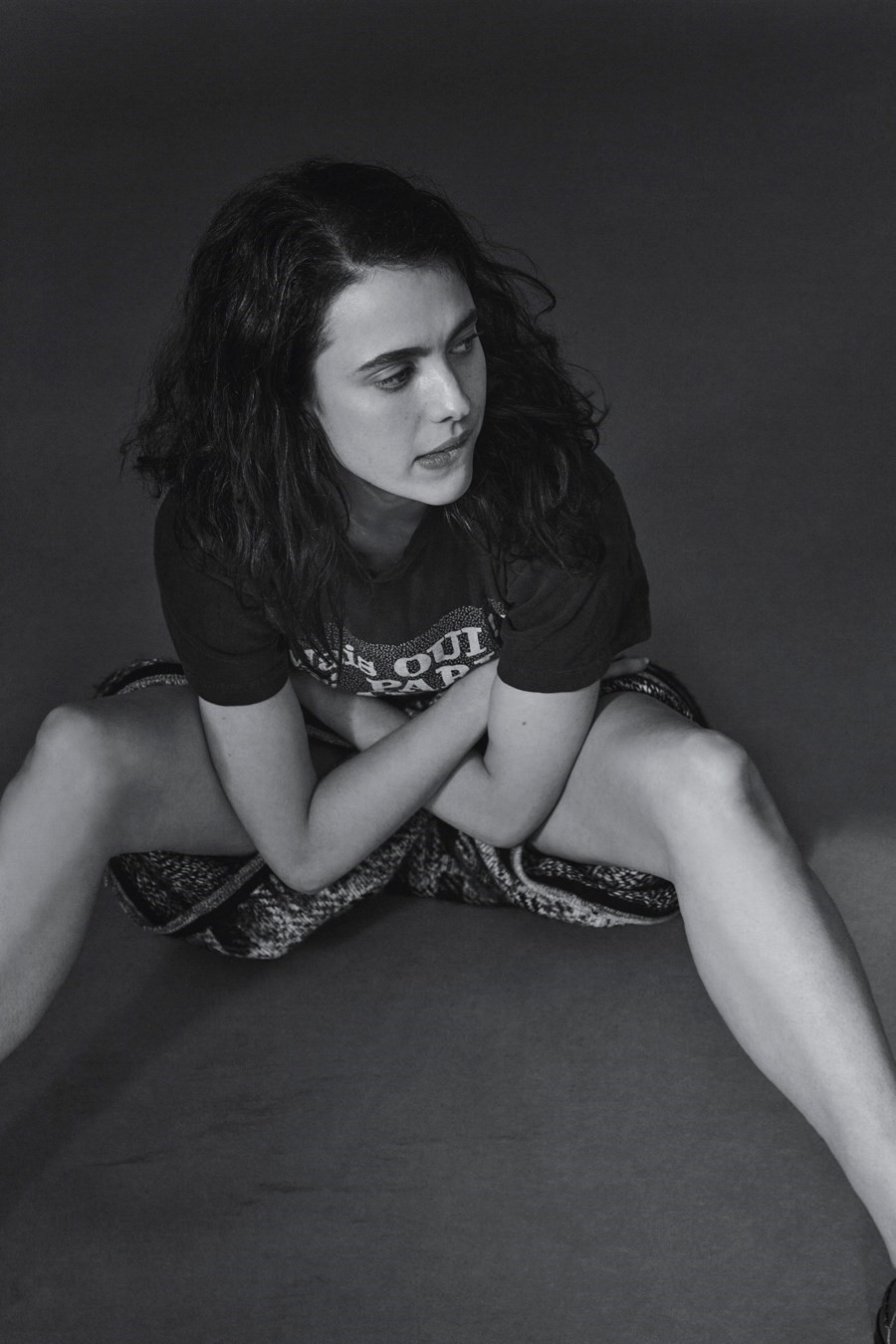

All CHANEL clothing and accessories from the Métiers d’Art 2022 collection.

Hair: James Pecis at Bryant Artists. Make-up: Dick Page at Statement. Set design: Ian Salter at Frank Reps. Manicure: Alicia Torello at Bridge. Digital tech: Jarrod Turner. Photographic assistants: Dylan Garcia, Tom Maltbie and Ariel Sadok. Styling assistant: Marcus Cuffie. Hair assistant: D’Angelo Alston. Set-design assistants: Russell Mangicaro and Robert Forbes. Production: Hen’s Tooth Production

This article appears in the Spring/Summer 2022 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale here.