This article is taken from the Autumn/Winter 2022 issue of AnOther Magazine:

Pierpaolo Piccioli wears a lot of black. He smokes a lot but he speaks more. And well.

He is one of that rare breed among fashion designers that has an innate ability to articulate the meaning and intent of collections through words, in manners that stretch far beyond their mere physicality. Piccioli is on a mission, has wide aims, grand ambitions: he sees fashion as a vehicle for communication, a way to project image and make people think deeper. His collections at Valentino have eschewed the ideas of luxury and aspirational lifestyle long associated with the label in favour of embracing an all-encompassing community.

The clothes are still luxurious, of course – lustrous silk, cashmere and mind-boggling embroideries, even in ready-to-wear. The craft in the haute couture goes stratospheric: capes pieced from thousands of fragments of cloth to resemble intricate prints; minute plissé columns of featherweight chiffon that seem constructed without seams; dresses that magically morph from taffeta into feathers, as if disintegrating glamorously before your eyes.

Yet if, in the past, Valentino created clothes inspired by objets d’art, by Aubusson carpets, or Delft ceramics, or Baccarat glass, like souvenirs of a life lived high, today Piccioli’s shows are motivated by more abstract ideas, by universal values. The clothes are exquisite, but through their presentation in fashion shows and campaigns they are animated in different manners, to different means. “Beauty was about glamour, success, hedonism,” Piccioli says. “And it was superficial.” Note, he speaks in the past tense. Because Piccioli harnesses his visions of fashion – his ideas of beauty – to communicate more than aesthetics, or the simplistic fashion message of “buy this dress”. Rather, he wants to promote values, to champion and embrace difference. “To me, beauty is about unity,” Piccioli says. But: “You are more special if you are different from the others.”

He also recognises that, rather than the mere hundreds who bear physical witness to his fashion shows every year, the message must go out loud to millions around the globe. “Fashion is now pop culture,” Piccioli says. “The big picture.” Images are worth a thousand words, as the cliché goes – which is why, as a writer, you’re often left scrambling to find ways to communicate the power of Piccioli’s vision, multilayered and glorious. And all that even before you begin to describe the clothes.

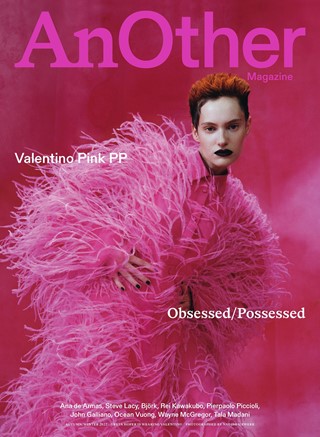

We talk a few days before Piccioli’s Autumn/Winter 2022 Valentino ready-to-wear show, in the house’s Paris headquarters in the Place Vendôme. It was here, in a series of stuccoed salons and to just 70 guests that Piccioli presented his Spring/Summer 2022 haute couture collection in January, dedicated to rethinking the ‘anatomy’ of couture. That show, fitted on a wide variety of body shapes and ages, attempted to break couture conventions of clothes engineered for figures startlingly slender, and of idealised youthfulness. “The beauty in humanity,” is how Piccioli described it, which underscores his approach generally. The Valentino space is abuzz with humanity – entire ateliers decamp here from Valentino’s Roman headquarters in the Palazzo Gabrielli-Mignanelli ahead of showtime, to fine-tune the clothes for models in the days leading up to each show. The passion of the craftspeople is palpable as they labour over pieces – and it is evident, here, that Piccioli adores fashion, adores the process of fashion as well as its imagery. He tenderly strokes dresses, cradles them, holding them aloft like the proud father he kind of is. This season his babies are all pink. Not just any pink, but a shade that Piccioli himself invented and named Valentino Pink PP, a marriage of his own initials with the name of Valentino, where he has worked for almost a quarter century – and where, after eight years working alongside Maria Grazia Chiuri as co-creative director, he has been sole creative head since July 2016. That name essentially sandwiches the colour between the label’s storied past and its future. Valentino is a forename rather than surname – taken from Valentino Garavani, who established the house in 1959, but who was, is and probably always will be referred to as Mr Valentino; Piccioli’s associates, by contrast, call him “PP”. Patrician respect versus playful nickname. There’s change afoot at Valentino.

The inspiration for the collection came, Piccioli says, from Lucio Fontana, the Argentine-Italian artist who described his monochromatic works as art for the space age. Painting using a single bold colour, Fontana then lacerated or punctured his canvases – he often lined them, like dresses, in black gauze to highlight the openings in their surfaces, and in his slicing of cloth to make two dimensions into three, his spatialism has an evident affinity with fashion. “I thought of Fontana and his way of cutting his canvas, his paintings, in order to find a new opportunity, a new space, a new dimension,” Piccioli says. He lights a cigarette. “I wanted to kind of reflect. A moment of reflection about my language of fashion, Valentino values, community. I felt that I have to use less.” What he decided to remove, of course, was colour. “Monochrome artists used to paint everything in one colour in order to give visibility to other things. To deliver different things, different emotions. For me it’s like a black and white picture book – after a chapter, you understand. And you go deeper into surface – the hands, the expression, the emotion. So I wanted to use one colour in order to highlight the idea of fashion as cut, design, silhouette, shape, volumes. Patterns, textures. You’re obliged to see more.”

“This collection was an invitation not to think with superficiality, but to have an open mind and see everything with fresh eyes” – Pierpaolo Piccioli

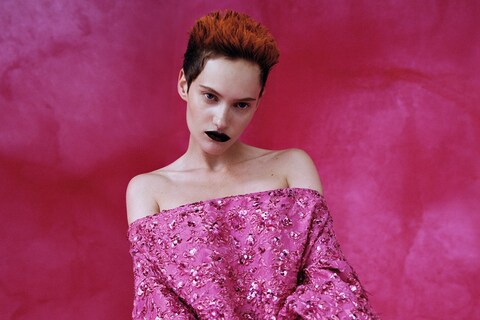

They also highlighted the individual. “You have to concentrate on the faces,” Piccioli said – and therefore on the people. Ironically, uniform colour became about individuality. Piccioli pauses. “Immediately what came into my mind was pink.” Pink is a weird one. It’s not a colour automatically associated with Valentino. The label has a colour, and it’s red – first used by Mr Valentino in his debut collection, for Spring/Summer 1959, in a short, strapless tulle dance dress named Fiesta, feistily abbreviated above the knee. But Piccioli felt oddly drawn to pink. “We don’t have to know why,” he says, of his attraction to pink. Piccioli likes a bit of mystery. “It is a colour I use in all my own collections, the very first with Zandra [Rhodes, who collaborated with Piccioli on his first Valentino ready-to-wear collection in 2016], then there was always one piece in that colour.” But if you push Piccioli he does have a reason. And of course it’s good. “Pink is maybe the colour that has the most progressive thoughts about it,” Piccioli says. “Sometimes it’s about prettiness, it’s about femininity, but actually it was the colour that in the 16th century was the colour of power because it was the colour close to the opera, all the reds. It was the most expensive dye and of course it was close to the church.” It still is today – worn by Catholic priests on the third Sunday of Advent and the fourth Sunday of Lent, as a colour of joy. “If you think of the Madonna, the most historical representation of femininity, it’s blue. It’s not pink,” Piccioli continues. “Pink before was a colour of power and masculinity. So you understand that it’s all about perceptions. This collection was an invitation not to think with superficiality, but to have an open mind and see everything with fresh eyes.”

As he speaks, a rail behind him seems to vibrate with the force of the shade. There are pink coats appliquéd with three-dimensional pink nosegays, pink silk shirt dresses frothing with pink ostrich fronds, a ballgown of operatic scale in rich figured pink brocade ... and an interruptive, disruptive section of clothes in black, like a murder of crows, all the darker for their context. Initially they seem incongruous – did Piccioli lose his nerve and think the collection needed some respite? But, upon consideration, they actually remind me of the gauze backing on those Fontana canvases, used to draw attention to the physicality of the cuts and contrast with colour. Piccioli calls it a “reset”. The collection’s opening look will be a crepe jumpsuit with a sculpted neckline soaring up towards the collarbone rather than down. Mr Valentino himself told Piccioli he adored that neckline. “For a reason that was completely the opposite of mine,” Piccioli comments. “For me it was because of the Madonna, the Renaissance goes to the street. For him, he told me, ‘This is great because this is the newest. Everyone goes down to show the breast, and you go up.’” Piccioli nods. “To me it was the meaning behind. For him it was exactly what he was seeing, the proportion. I think it says a lot about how we work differently.”

It was a bold, confident and gloriously illogical move from a designer who, arguably, has one of the best senses of colour since Christian Lacroix burst onto the scene in 1987. Piccioli has been rightfully celebrated for it: he is already pitched up there with Yves Saint Laurent in the pantheon of greats (Saint Laurent is, of course, a figure he worships). It stands in literal bold contrast to his personal uniform of habitual black, also the polar opposite of the white-coated figures who people the atelier – many of whom have worked at Valentino for 20 or 30 years.

There may only be one colour this Autumn/Winter but Valentino Pink PP is no random choice – it was specifically developed in collaboration with Pantone, which holds more than 15,000 colours in its database. The colour is, Piccioli states, a step below fluoro – but only just. “I gave them the pink,” Piccioli states. “I said, ‘This is the pink I want.’ I did it with the fabrics and then I gave them the pink in order to find the formula. I had to use one formula so as to align the balance between magenta and cyan, in order to create that shade. Vibrant but not fluoro.” The truly exceptional element in this show was how that single hue was applied across an entire spectrum of fabrics and finishes – extending even to the models’ make-up and the show’s venue. As tends to be the case, the simplest idea is the most complex – unifying that colour across not only woven textiles but a physical space was a painstaking exercise. But ultimately it worked. With limbs smothered in gloves and stockings, laid against the pink backdrop in their pink clothes, at some points models wound up resembling a floating, surrealist bust, real life made unreal. “Like she was cut out,” Piccioli says.

“Pink is maybe the colour that has the most progressive thoughts about it. Sometimes it’s about prettiness, it’s about femininity, but actually it was the colour that in the 16th century was the colour of power” – Pierpaolo Piccioli

The collection began life in a very different fashion. Valentino’s Spring/Summer 2022 ready-to-wear show was staged in the Carreau du Temple, a former covered market in the 3rd arrondissement of Paris that underscored a feeling of reality, of life. The models wandered through the building, then strode out onto the streets of Paris for a clustered public audience of several hundred to watch. Piccioli first envisaged his Autumn/Winter 2022 underscoring that feeling – scouting locations, he was considering schools and universities, “places where there is life”. He was scouting in December 2021, however, during a spike of Covid-19 infections across Europe. “It was still a weird moment,” he says. “It was not actually the moment I wanted to witness.” That idea is something Piccioli returns to, again and again. He is aware of a duty, in his work, to reflect the world around him – the breaking-down of prejudices and conventions, the reflection of shifted notions of beauty.

“When you’re good at catching the zeitgeist, it’s something people will remember for years,” he says. “It’s about your time, but it’s about witnessing your time in a way that will stay.” His collection debuted just ten days after Russia invaded Ukraine. Piccioli didn’t plan his collection as a response to that but the global situation reframed his ideas. “I always think that hope and creativity are the only things we have to destroy the darkness of the moment,” he says. “I don’t think you can say anything about war, because the war is not about people. It is about money, the economy and the madness of single individuals. So they don’t have sensitivity. Fashion can talk about social sensitivity, you can lead people in thinking in a different way, which is great, but I don’t think that is done with a T-shirt reading ‘No War’. Everyone is against war.” Piccioli pauses. “I think it was good not to be in reality for that moment.”

Piccioli was born in 1967, and grew up in Nettuno on the Tyrrhenian Sea, about 60 kilometres south of Rome. He still lives there, surfing every day and, indeed, is kind of an everyday guy, who transforms during his daily hour-or-so commute into one of the most powerful creatives in fashion. He studied literature at Sapienza University of Rome, alongside fashion design at the city’s Istituto Europeo di Design (IED), which created an interesting dichotomy, one still evident in his designs today, where he will mix up references to punk and Piero della Francesca and Pier Paolo Pasolini and mathematicians of the Renaissance, evidently a favoured period. He begins each collection, he says, by looking at the same collection of books on those subjects because, like the deluge of pink in his Autumn/Winter 2020 show, he likes to see familiar things with fresh eyes. Antonio Mancinelli, the Italian journalist and professor who taught Piccioli at the IED, referred to him as a poet. Lots of people use that description – myself included – possibly a hangover from those literary studies, which have influenced his way of expressing himself through to now. He has even commissioned a number of poets and writers, from Yrsa Daley-Ward and Mustafa the Poet to, this season, Douglas Coupland. “Pink is a form of freedom that exists maybe nowhere else in the realm of colour,” Coupland wrote – and it could have been Piccioli talking. Then he continued, “Pink is a very sweet cake you can’t eat too often, but when you do, there’s no other cake like it.” That’s less Piccioli. His Valentino clothes are poetic, though. While generally, poetic in fashion means a sense of grace, elongated dresses in filmy fabrics with a romantic bent, Piccioli’s poetry spans the whole gamut. There are collections that are epic, in the tradition of Virgil’s Aeneid or Milton’s Paradise Lost, those gluts of pure colour, these trailing grand capes. Others mix high and low, classic and pop, like TS Eliot’s The Waste Land, or reflect the brutal modernity of Allen Ginsberg’s Howl. And, of course, there’s some of the lighter stuff. Valentino is really great at those pretty dresses.

Piccioli says that his dual studies marked him out early. “When I was in my twenties, I preferred to not belong to anyone,” he says. For his friends at the private IED, he was the “radical” guy; at Rome University, he was marked out with the privilege of attending a private school. “With my gay friends I was not gay enough because I had a girlfriend,” he says. His “straight” friends all assumed he would turn out gay. “I was doing fashion so they thought, ‘Maybe you’re not aware but you will discover soon.’” Piccioli laughs. That didn’t come to pass – he’s now married to his girlfriend from back then, Simona Caggia, whom he met at high school. They have three children. “But you understand that that’s your strength, not to be with anyone but being alone and you find your own way, balancing all the stuff together, even if people don’t understand.”

“When you’re good at catching the zeitgeist, it’s something people will remember for years,” he says. “It’s about your time, but it’s about witnessing your time in a way that will stay” – Pierpaolo Piccioli

Piccioli doesn’t mind sometimes confusing people. He has been making broad sweeps in his recent collections, seeking to evoke ideas and emotions that run deeper than the surface. The aforementioned spring haute couture collection wasn’t just a gesture towards inclusivity but, Piccioli said, an attempt to shift the bodies we idealise through the process – five fit models were used rather than just one, a spectrum of ages and shapes. The couture collection he showed in July, in Rome on the rococo Spanish steps around the corner from Valentino’s historic home, reimagined grandiose images of models descending the travertine slabs that Piccioli remembered from his teenage years in the 1980s. In Piccioli’s rework the models were markedly different – all genders, a variety of ages, shapes, disparate heritages. ‘Diversity’ doesn’t really cut it as a label – maybe ‘inclusive’ is better, the opposite of exclusive, which so many fashion houses have aspired to be. We meet again in Rome just after that show. Like almost every room at the house of Valentino, Piccioli’s office is grand, with a vast vaulted ceiling soaring overhead. The building is owned by the Holy See and the room kind of feels like a chapel. Outside his long windows you can see La Colonna dell’Immacolata – the Madonna who Piccioli references a lot. She’s stomping on a serpent, a symbol of original sin, which weirdly Mr Valentino wriggled over lots of dresses during his career. It’s a motif Piccioli uses sometimes, too.

The sneakered Piccioli and the impeccably attired Mr Valentino seem aeons apart – in their personal wardrobes, their backgrounds, indeed their lives. Valentino was fixated on fashion from the age of four – indeed, he was so sartorially obsessed that he cried until he vomited when his mother made him wear a “vulgar” bow tie with a new, brass-buttoned blazer. He was six. His precision came out in his couture clothes, but also in his lifestyle, in a retinue of 50 staff who keep five international homes in a state of incessant Architectural Digest readiness, flowers permanently arranged, sheets ironed twice (once after washing, once on the bed). Yet there is undoubtedly an affinity between their approaches, their feeling for beauty, their respect for couture. Mr Valentino and his former partner Giancarlo Giammetti are conspicuous presences at many of Piccioli’s shows, leading standing ovations. And, in turn, Piccioli said his Autumn/Winter 2022 couture collection was about “how much of me is in Valentino, and how much of Valentino is in me”.

Talking of broad sweeps, this one was at the Valentino archive, its heritage and meaning. Piccioli is working on a retrospective exhibition, Forever – Valentino, to be unveiled in Doha, Qatar, in October of this year. The richness of the Valentino archives is astounding. The more you look, the more you see: their influence is woven through the clothes Piccioli creates. In the Valentino Pink PP collection there’s a dress with a bow-knotted bodice, open on bare skin, which throws back to the model that closed Mr Valentino’s Spring/Summer 2002 ready-to-wear show. You find colours close to that nearly fluoro pink in Valentino’s past, too: in a slender crepe column dress with tucks criss-crossing the heart, and in another fashioned as a great bubble of taffeta, bodice swung over one shoulder and bunched into a thick bow at one hip. In earlier couture shows, Piccioli has revelled in the theatricality of ‘jellyfish’ hats, created by Philip Treacy, with floating fronds of ostrich feathers – which have a direct antecedent in a Valentino collection from 1993. For his latest haute couture collection, Piccioli created a dress inspired by that 1959 model, Fiesta: his take is a great glob of fat cabbage roses in red silk faille that entirely encased the torso of the South Sudanese model Alaato Jazyper Michael. “One of the journalists asked me, ‘How many roses are on the coat?’” Piccioli rolls his eyes. “I got crazy. I thought, count them if you really want to know. Just count ... is that important?”

Piccioli isn’t saying fashion is unimportant, though. He believes it is, profoundly. “I think this work is obsession,” he says. “I’m very, very obsessive with everything. With every single detail, the rhythm, everything ... So it’s obsessive. The way I work is obsessive.” You sense that with Piccioli’s flower-smothered dresses, and intricate intarsias, and trailing capes that often seem spontaneous and instinctive but, in their actuality, demand a precision only possible at the hands of couture ateliers. Maria Antonietta De Angelis, a premiere of one of those – the longest-serving, with 36 years’ experience – was fitting a ruffled limoncello chiffon dress to a teenage male model called Timothé ahead of the July couture show. Piccioli laughs as he recalls that, rather than being nonplussed by a dress worn by a man, De Angelis fixated on the waist. “She was obsessed with the proportion,” Piccioli says. “Obsessed by the waist, by the dress, but she doesn’t care about the big picture. Because it’s not her obsession. Her obsession is how the dress fits.”

Hair: Virginie Moreira at MA and Talent using BUMBLE AND BUMBLE. Make-up: Ammy Drammeh at Bryant Artists using Tone on Tone and No 1 de Chanel Essence Lotion and Body Serum-in-Mist by CHANEL. Models: Greta Hofer at Elite Models, Chloe Oh at Premier Model Management, Avanti Nagrath at Select Models and Anyiel Majok and Goy Manase at PRM Agency. Casting: Jonathan Johnson. Movement director: Benjamin Jonsson at Box Artist Management. Set design: Ibby Njoya at New School. Manicure: Saffron Goddard at CLM using Manicure Collection and Miss Dior Hand Cream by DIOR. Photographic assistants: Meshach Roberts, Matt Moran and Jaye Gilbert. Styling assistants: Molly Shillingford and Precious Greham Johnson. Hair assistant: Marina Demetriadis. Make-up assistants: Quelle Bester and Tamsin Ballingall. Set-design assistants: Axel Drury, Sam Edyn and Mick O’Connor. Production: CLM. Post-production: Touch.

This story features in the Autumn/Winter 2022 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale internationally now. Buy a copy here.