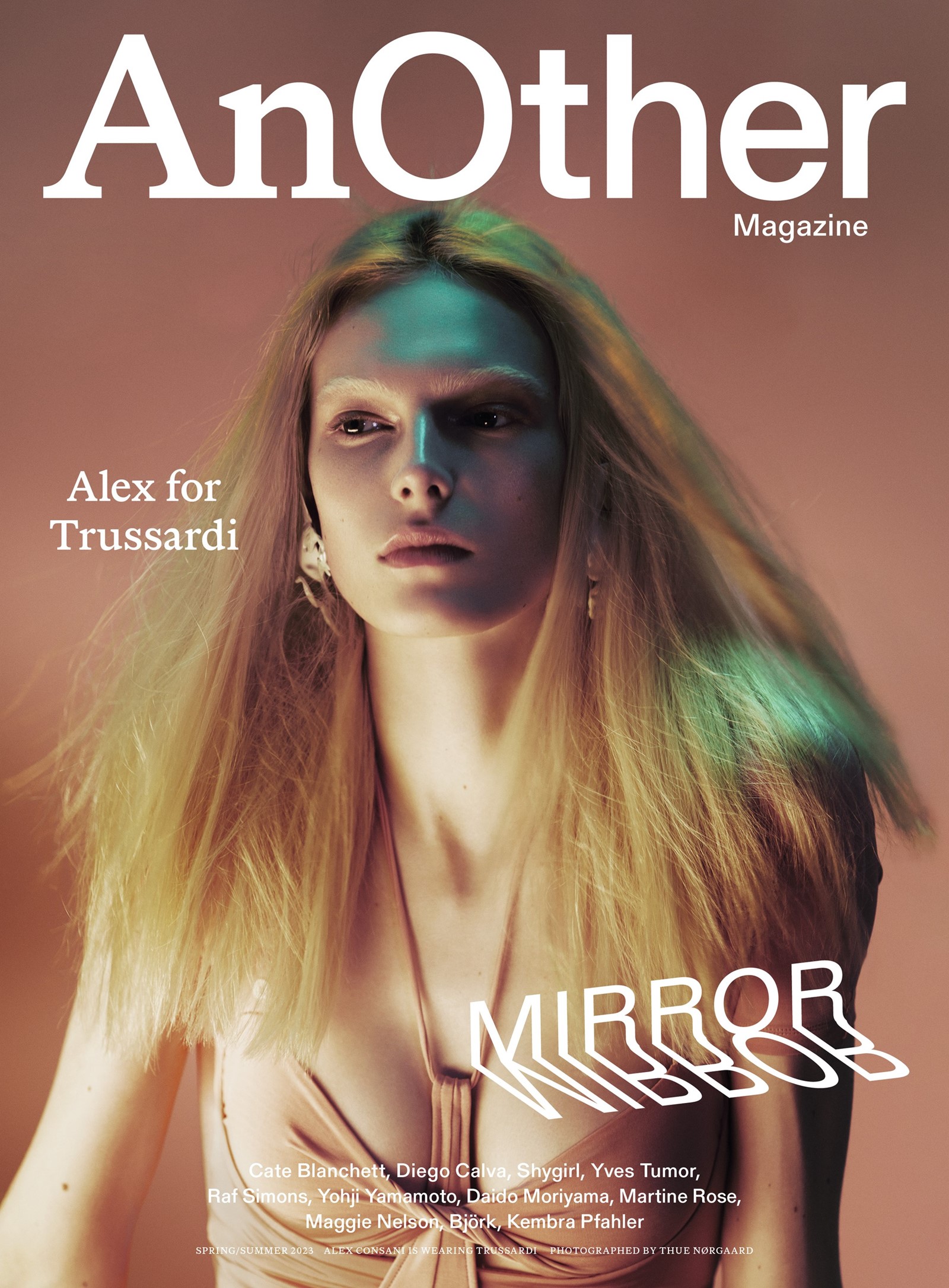

This article is taken from the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of AnOther Magazine:

When the Berlin-based label GmbH showed its first collection back in 2016, the idea that its designers, Benjamin A Huseby and Serhat Işik, would take the creative reins at a heritage Italian luxury house may have seemed unlikely. Powered by the energy of their artistic community in Berlin, their work at GmbH – the term for ‘limited company’ in German, chosen by the designers for its anonymous tone – has been about exploring identity: as brown, as queer, as the children of immigrants (Huseby is Norwegian-Pakistani, Işik Turkish-German).

But in 2021 the two were named creative directors of Trussardi – the Milanese brand with more than 110 years of history under its leather belt. Their appointment was a reflection of two things: the ways the industry had caught up with their vision, and of GmbH’s singular design language, fuelled by deep research and an ability to explore and elevate even the most banal of fashion tropes.

Their first collection for Trussardi took to the catwalk in February 2022, the opening look setting the mood. A Milanese fashion staple – the puffy piumino jacket – was transformed in leather and cropped to show stretches of midriff, appearing alongside pieces that fused historical European dress with the 21st century, including a Renaissance-style corset reconsidered in black leather with white stitching, a motif lifted straight from the Trussardi archives. For Spring/Summer 2023, inspiration came from closer eras, the Eighties and Nineties, but again there was a reworking and updating of silhouettes that might otherwise be lost in time. Yet there’s more to Trussardi than the catwalk collections: with an acclaimed restaurant and a furniture line (Huseby and Işik showed its first new project last year at Milan’s Salone del Mobile), Trussardi is a universe unto itself. And for the designers it’s a unique platform – an opportunity to be part of the house’s celebrated history, yes, but also to showcase new ideas and uplift the next generation of creative talent.

Emma Hope Allwood: You first met while clubbing, but what was it that brought you together creatively?

Serhat Işık: At some point us meeting on the dancefloor became this myth. It’s true, but that’s sort of how everybody meets in Berlin.

Benjamin A Huseby: We were recently saying that we should invent a new story.

SI: I was working as a freelance designer when Benjamin and I met. He had some very specific ideas for a collection that I could help with because I had the setup and the skills. I think what connected us both immediately was storytelling. We realised how similar our ideas were and also the things we were interested in – political issues, reflecting on how the industry has been lacking diversity. We were both inspired by wanting change, that’s sort of how it started.

BAH: It was never really about ‘diversity’ – it was about representing our community in a very true and honest way that we didn’t feel was represented at the time. GmbH is a project of decolonising our minds. It’s about unlearning what we were told, how we were taught to see ourselves as children of immigrants, as brown, as queer. And it’s always been about shifting the ideas of beauty.

SI: If you, as an immigrant, show up in a tracksuit at a doctor’s or lawyer’s office in Germany, you’re going to be treated differently, right? There are these presuppositions of clothes and codes that devalue your existence. So there was always this interest of wanting to elevate anything that could represent our community, to find beauty in that.

EHA: Casting was obviously one way you explored that representation.

BAH: We realised we could use the casting to express and communicate a lot of these ideas. I think we also started making collections at a time when there was an audience for what we were talking about – in that way we were very much part of the zeitgeist.

SI: When we started our casting was called “aggressive” because it was predominantly brown and black. It was a very common question in the beginning with our first shows and presentations – “Aren’t you afraid to be so political?” This was only four or five years ago, and in such a short amount of time it became the norm, trendy.

BAH: While that’s obviously great in some ways, when bigger brands do it, it often feels like it’s to tick boxes. So it’s a bit of an ambivalent space to be in. But I think we’ve reached a point where casting isn’t the main focus – it’s not a distraction for people any more. There is so much else that we can talk about, and I think now we’re able to create stories that are much more intricate and deep.

EHA: Let’s talk a bit about the most recent GmbH collection ...

BAH: The Spring/Summer [2023] collection was named Ghazal – it’s a poem form that is used a lot in Iran and Pakistan and other nearby countries. It’s kind of a love poem set to music that often has a very melancholic side to it – it’s a lot about separation. We showed this collection shortly after the [75th] anniversary of the separation of India and Pakistan. So I thought it was a rare opportunity to really embrace and show South Asian and particularly Pakistani ideas of beauty and culture. It’s not something that you often see on the runways in Paris.

SI: This collection was very rewarding – how the South Asian community reacted to it.

BAH: I definitely think, in the beginning, our work was seen by an audience in typical global fashion hotspots like London and Paris and Tokyo and Berlin. Now I feel like it’s popping up everywhere – this show seems to have had a bit of a viral moment in Pakistan.

“I thought it was a rare opportunity to really embrace and show South Asian and particularly Pakistani ideas of beauty and culture. It’s not something that you often see on the runways in Paris” – Benjamin A Huseby

EHA: Trussardi represents something quite different from what you’ve been doing with GmbH. How did the opportunity come about? How did you feel about it?

BAH: We were headhunted – I guess that’s the word. We thought it was a very interesting project because it felt like a blank slate – a brand that people of our generation might have heard of but not have expectations of. There was a sense of possibility.

SI: It felt like a unique opportunity. If you think about it, how many houses are there left with this kind of rich history that has been untouched?

EHA: What caught your attention when you started delving into the brand?

SI: What we’re interested in is taking codes that are so archetypical for clothing, for people, for culture, and really making them our own – even if they aren’t necessarily the first thing of interest to us. So there was this aspect of looking at Milan and how people dress – we realised these piumino jackets were literally the T-shirt of Milan.

BAH: We were observing people on the street, trying to understand the codes. I think from being an outsider in Milan, obviously you see things a little bit differently. We’re always interested in bringing things that are considered too banal or not stylish or not tasteful and redefining them, creating something new. In many ways, it’s a very personal reflection for us of what we see as Milanese style.

SI: Mixed with the richness of the archives.

EHA: What did you find in the archives?

SI: There’s a lot of sex appeal – all these Eighties crystal dresses, crystal bras and chokers and big jewellery. There’s a lot of fashion there for sure, things that even people who work for Trussardi wouldn’t necessarily expect to find. Those were the moments where you walk into the archives and you’re like, I see this on this or that artist, or I know this is going to be a hit. It’s been extremely interesting to work with, even just from the perspective of loving garments.

EHA: Your work is so much about your own heritage – was it strange shifting gears to think about Italian style?

BAH: Well, since the very beginning at GmbH we spoke about how much Italian fashion – classic Eighties and early Nineties – inspired us. I grew up with a dad who’s obsessed with Italian fashion, he always wears a suit.

SI: Italian fashion was always very highly regarded in, let’s say, the Middle East, or by our parents and their generation. I remember my dad being way more drawn to Italian fashion.

BAH: Armani, all that, particularly the menswear. That chicness of that really classic Italian fashion.

EHA: How does your practice differ across the brands?

BAH: Research is the foundation of everything we do, both at Trussardi and GmbH. I think there’s an anthropological interest in codes, in history – both within fashion and our own, personal histories – and trying to connect all these past and present influences into a new language, new forms. There’s always this saying that everything has been done before, but it’s about putting things into new contexts, you know, recontextualising a women’s mid-century couture silhouette on a man, for instance.

“It felt like a unique opportunity. If you think about it, how many houses are there left with this kind of rich history that has been untouched?” – Serhat Işık

At Trussardi, it’s the first time we’re so intensely focused on womenswear, so it really makes sense to enrich that with our interest in feminist theory. There’s this Italian-American academic we love called Silvia Federici, who we referenced a lot in the [Spring/Summer 2023] show – particularly her work Caliban and the Witch. She has this theory about how the witch-hunts and the persecution of women moved women out of their work, where healing became kind of disenchanted and primarily handed over to men.

That became a parallel narrative that was very interesting for us because we were working with a very chaotic, nonlinear idea of history. For Trussardi we’re playing with the historical aspects of the house and also playing with history itself, mixing myth and fantasy and history together.

EHA: How are you thinking about the universe of the brand outside fashion?

SI: We work very collaboratively at GmbH, with artists, friends, musicians, so at Trussardi we are obviously creative directing but we’re also curating a community. That’s how we did our first furniture line, with three artists who we invited to design these items. And I think in many ways that’s also the foundation of Trussardi. That’s really the core value of the brand that resonates with us very much.

BAH: This idea of curating is quite interesting for us.

EHA: And when it comes to curating a community for Trussardi, what kind of people do you feel like you want to bring into the brand?

BAH: We’re thinking about it as a very creative brand, so it’s across cultural, creative industries – art and music and so on. It was interesting to look at Milan ...

SI: ... and the diverse community of Milan, a city we don’t know that well.

BAH: This furniture collection was an important first step in building some of that sense of community. There’s a whole new generation, which is maybe not what people associate with Milan, that is very different from the kind of clichéd, slightly more conservative and stuffy stereotype.

EHA: Tell me about developing the visual side of the brand – the logo, for instance.

BAH: The logo was a very exciting part. We wanted the word mark that says ‘Trussardi’ to feel like it had always been there, but still modern and contemporary – so people wouldn’t know if it was from 30 years ago or now. Then the ouroboros logo is a reinterpretation of the greyhound symbol, which has been a brand motif since the Seventies.

The cyclical life of fashion was important to that, trying to put ourselves into that historical context. Unlike GmbH, Trussardi is not about us. It’s about us trying to place this house into historical context. That’s what the logo represents – it’s biting its own tail. It’s the idea of rebirth.

SI: Trussardi is one of the oldest brands in Italy, so we really wanted to reflect the infinity of that.

Hair: Soichi Inagaki at Art Partner. Make-up: Inge Grognard at MA+Talent. Manicure: Linda Derbali. Models: Aditsa Berzenia at Ford Models, Alex Consani at IMG Models, Ajah Angau, Anass Bouazzaoui and Gendai Funato at The Claw, Biar Ayiei and Ornella Umutoni at Select Model Management, Diane Chiu at Premium Models, Sunmoon Jung at Tigers by Matt and Avanti Nagrath at Women Management. Casting: Daniel von der Graf and Andrea Prato. Set design: Giovanni Martial at Artlist Paris. Digital tech: Lorenzo Touzet at D-Factory. Lighting: Christian Bragg. Photographic assistant: Anton Grebentsov. Styling assistants: Precious Greham and Lina Velasquez. Hair assistants: Myuji Sato and Natsumi Ebiko. Make-up assistants: Clara Barban, Caroline Joos and Claire Urquhart. Set-design assistants: Jeanne Briand and Anatole Chartier. Production: Town Productions. Production assistants: Christian Mupondo, Thi-Léa Le, Sarah Bailly and Agathe Halin

This story features in the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale internationally on 23 March 2023. Pre-order here.