This excerpt is taken from the Britishness chapter of Burberry by Alexander Fury, which is published by Assouline and is out on March 28.

“Show me the clothes of a country,” said the author Anatole France, “and I can write its history.” The clothes of Burberry are intrinsically tied with the history of Britishness, as perceived in the popular consciousness – in actual fact, they are woven into British identity, still unspooling and evolving, as changeable as fashion itself. “Burberry is a British institution and has been since it started in 1856,” says the model Naomi Campbell, who has modelled in a number of Burberry campaigns, most recently for the Summer 2021 Monogram campaign. “In a way, you feel like you’re representing your country. I feel that British style and attitude always lead the trends. We don’t just wear it, we live it.” “Burberry is the quintessential British brand. For those of us who grew up in London’s fashion scene in the Nineties, it’s part of our DNA,” says Edward Enninful OBE, editor in chief of British Vogue and European editorial director of Vogue. “The past two decades have solidified Burberry’s position as a heritage brand that remains on the cutting edge of fashion and culture.” As Enninful and Campbell both identify, from the very beginning of Burberry’s story to the present day, qualities universally considered fundamentally British have been woven into the fabric of its clothes. They are not an inspiration, but an ideology. They shape Burberry.

Britishness, however, is a malleable and elastic term. Many have tried to pin it down; most have failed. Perhaps because Britishness is paradoxical and contradictory, composed of opposites, attracting one another and coexisting. The pomp and circumstance of royalty, of history re-enacted, sits alongside pragmatism, common sense, a dislike of complication. A love of mythology, of fable and fantasy, butts heads with a distinct distaste for over-elaboration. A society rife with uniforms of every description yet filled with rebels who tear them apart at the seams. All are elements that are fundamentally, unmistakably British yet each, at least on paper, defeats another, ironically. Irony is a very British quality, too.

Burberry was born in Britain, and hence naturally carries many of the strongest signifiers of a collective, international notion of Britishness. In the eighteenth century, a fad burgeoned in France for fashion perceived as British – they dubbed it ‘Anglomania’, and the clothes associated with it were simple, well-cut, in linens and wools, unadorned, their easy lines influenced by aristocratic sporting pursuits. Fashion’s reflection of Britishness has tended to hew along that path – ideas of function and utility are key, hence perhaps the reason that, a century later, Thomas Burberry’s streamlined outerwear in luxurious yet eminently practical fabrics rapidly came to convey Britishness worldwide. Britishness also embraces its own clichés – Burberry’s focus on the weather, on weatherproofing, seems engineered with a wry nod to the notoriously inclement climes of the British Isles, and the British propensity for discussing them.

“I think any national identity is hugely determined by landscape,” says Professor Amy de la Haye, Rootstein Hopkins Chair of Dress History and Curatorship, and Joint Director of the Research Centre for Fashion Curation at London College of Fashion. “So the colours, I suppose, of our fashion are not surprisingly camouflage within our actual environment. Tweed is the colour of heather, of grass; gabardine is the colour of straw.” An obvious link here is gamefeather tweeds, much used by Burberry around the turn of the last century. Advertised at the time by the firm as “rich rare colourings, effects which appeal at once to those of artistic and sporting tastes,” the tweeds were artfully blended to mimic the colour of British gamebird plumage, acting as camouflage for its wearer when out in the field – particularly suitable for capes and weatherproof overcoats. Burberry advocated its use for golf, cycling, angling and out-of-door exercise, in styles for all genders.

“I’m British. I grew up here. Burberry was woven through the culture that I was a part of,” says Christopher Bailey. “And that begins with Thomas Burberry. That’s why he was a genius – because he was the one that linked Britishness to the coat, and then used that as marketing, at that time, in different ways around the world. It was revolutionary.”

“You have the Queen, aristocracy, culture, elegance, perfection. Then you always have this other side. Punks. That is the beauty of Britain” – Riccardo Tisci

That idea – of a different outlook, a new perspective, on Britishness, is vital. Burberry’s view of Britishness is for the world – conscious of an outside view of British foibles and idiosyncrasies, conveying what is seen as the national character. Importantly, Britishness is about far more than surface, especially in clothes – it isn’t just in the cut of a tailored suit, the zips and raw-edged rifts of punk, or the practical yet polished look of a trench coat, but also in the thought processes behind both their creation and their wearing.

Words like ‘democratic’ and ‘egalitarian’ come up when speaking about British clothes – and when speaking about Burberry. Gabardine drew inspiration from the clothes of working people, the humble smocks worn by farmers and shepherds, engineered for all in the great outdoors. Later, the Burberry trench was drawn from the world of uniform, again with a universality. Part of the appeal of the aforementioned French Anglomania was that it was a sartorial stance against the autocracy of the French monarchy. Those are tied in with ideas of practicality, of course, the notion that British clothes are born, often, from pragmatic concerns, based in workwear – although workwear could as easily be a tailored suit as a fisherman’s sweater. The Burberry trench also epitomises the notion of purpose: every element, stylish as it may be, was devised as a result of need, a reaction to action, a reflection. Of living.

Despite its competing contradictions, at the heart of Britishness lies an enduring sense of community and of altruism – giving back to society, caring for one’s neighbour. Those ideals have been part of the fabric of the nation for centuries. “How I would understand Britishness to be a positive attribute, would simply be to be tolerant,” says Nick Knight, the British image-maker. “Intellectualism, a gentlemanliness. Being strong, but helping the weak, people in need.” These ideas chime with those of Thomas Burberry and were reflected from the very start in his company: in 1863, at the age of 28, Thomas took on a voluntary position assuming responsibility for the funding of the poor in Basingstoke, and throughout his life he was markedly altruistic, welcoming those in need of food and drink into his home. In 1915, the Burberry company donated a motor soup kitchen to the British Red Cross, while after the Great War, in 1918, Burberry began the Blighty Tweed programme, employing disabled war veterans and training them in a new skill – to weave tweed.

That Burberry ethos – that British sense of care, of giving back to society – is woven into the company, present through to today in numerous charitable initiatives. In 2020, the English international footballer and youth advocate Marcus Rashford MBE was photographed for Burberry’s Festive campaign – highlighting their partnership to support youth charities, united with Rashford’s fight against child hunger and drive for societal change. “My partnership with Burberry was built from our aligned vision to progress work in the community and offer opportunity to those in underserved areas,” Rashford says. “To inspire and to motivate. Whether it be financially supporting youth centres that are integral to the community, or building libraries to promote the joy of reading in primary schools that are financially restricted, we have done a fantastic job of offering stability to children up and down the country, whilst also allowing them to see a world beyond just what they see on their front doorstep. It’s a truly valuable partnership.” Fittingly, in his debut Burberry campaign, Rashford wore a cape – like a superhero.

Britishness, to Rashford, is about consciousness. “People are more conscious of the power of their voice than ever before. People are more conscious of their buying habits and sustaining a better planet. Britishness is individuality. We tend to dress the way that we feel. We are diverse. We are blended culturally.” Fundamental ideals of community and citizenship have always been at the fore – today, as Rashford says, those ideas are often expressed through fashion, where choices of clothes connect a wearer, emotionally, to the values of a brand – and furthermore bind together wearers from different backgrounds, their attire acting as markers of mutual belief systems, shared ideals. Identifying their tribes.

Riccardo Tisci is Italian – so he is, perhaps, well situated to observe those ideas of Britishness. For him, his work at Burberry is an exploration of the notion of national identity – its ever-transforming nature affording license to explore disparate themes and iconography. “Extraordinary, over-the-top, the countryside,” is one way he has described Britishness, colliding just some of its many contradictions. “This country, in history, is the most representative country of duality,” Tisci said on another occasion. “You have the Queen, aristocracy, culture, elegance, perfection. Then you always have this other side. Punks. That is the beauty of Britain.”

“Burberry is a really democratic brand, in the sense that everyone regardless of class or age can find a way to make it their own” – Jefferson Hack

Punk is a modern phenomenon: it was born in the 1970s, but it represents a deep seated spirit of rebellion that is also perceived as distinctly British. It was present – discernible still – in Thomas Burberry’s daring innovations, unconstrained by societal norms. He dared to push beyond conventions and explore new territories, challenging the status quo – taking inspiration from rural life and translating it into urbane clothes, elegant yet rational. Rebels continue to inspire: if, in the mid-twentieth century, perceptions of Burberry skewed to the patrician and aristocratic, today they have been reset. Collections have been influenced by punks and mods, by casuals – the 1980s youths who wore Burberry as a badge of aspiration, another means of asserting identity. They connected with Burberry’s storied history, but effectively managed to subvert and challenge its meaning, to resignify it.

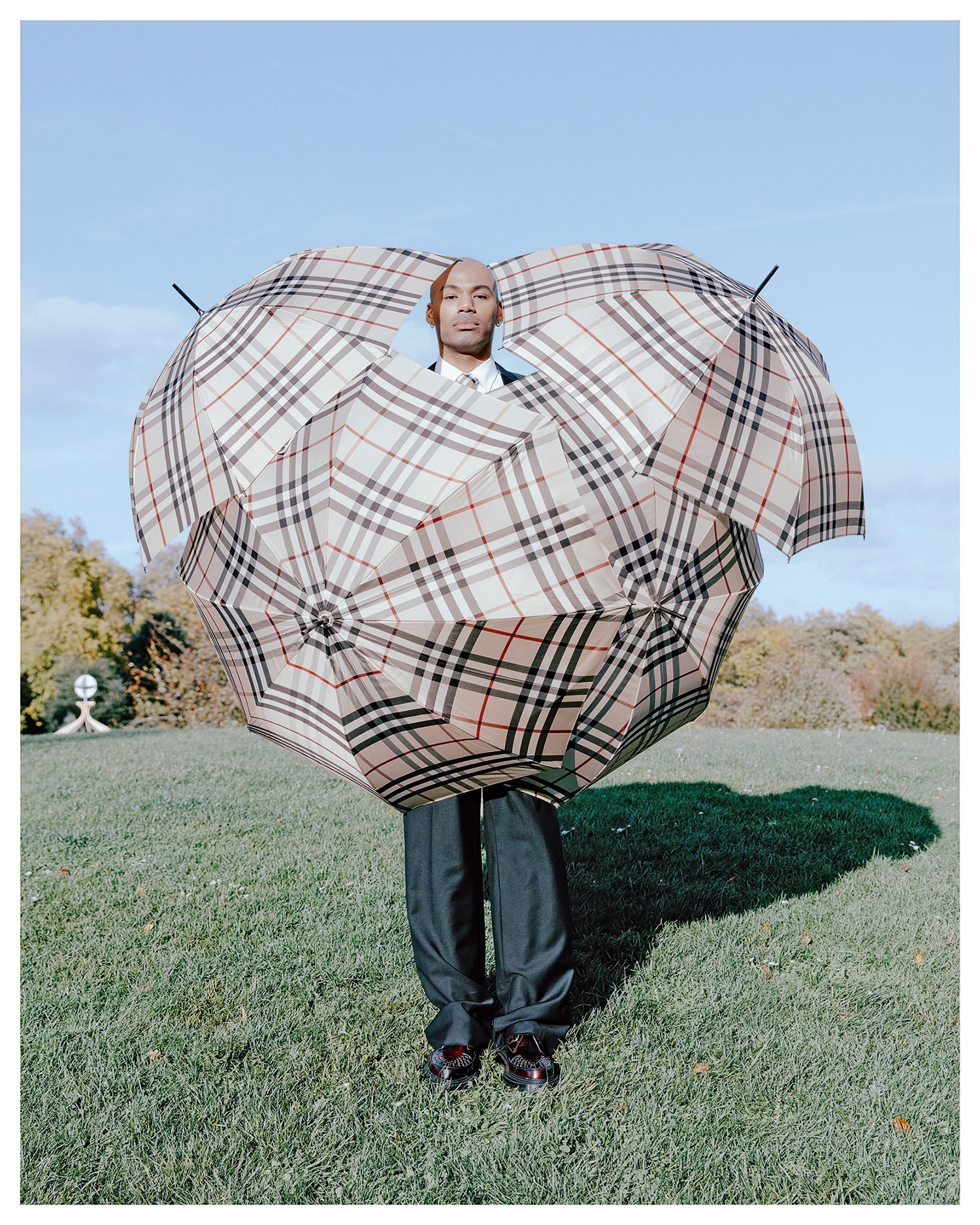

One of Burberry’s great signifiers is, of course, the Burberry Check, a streetwear uniform since the early 1980s, when it became a representation of affluence and youthful aspiration. It held the same meaning in the mid-1990s when, representative of Britishness, it became a sartorial symbol of ‘Cool Britannia’, worn by figures such as Liam Gallagher of the Britpop band Oasis. “As the Check is so iconic and loaded with cultural significance, it becomes constantly subverted by new generations,” says Jefferson Hack, the founder and editorial director of Dazed Media – and, in 1991, cofounder of the magazine Dazed & Confused. He is both a documenter of the cultural zeitgeist and one of its influencers. “I loved it when Skepta wore the tie-dye Burberry Check puffer,” Hack adds. “Burberry is a really democratic brand, in the sense that everyone regardless of class or age can find a way to make it their own.” And for him, British identity is tied up with creativity, with youth and music. “This small island has produced some of the most original music, art, theatre, dance, architecture and entertainment in the world,” Hack states. “Our creativity and our eccentricity is core to how the world views the UK.” It is at the core of Burberry too.

Burberry by Alexander Fury is published by Assouline and is out on March 28.