Curator Eldina Begic talks us through five key workwear pieces from her Rotterdam exhibition – from a NASA space suit to early Stone Island and CP Company pieces

“I didn’t want to focus on a very common idea of workwear, like showing a blue work jacket, or the first pair of jeans,” says Eldina Begic, the curator of new show Workwear at Het Nieuwe Instituut, Rotterdam. “For me, it was more interesting to show its potential, and this really exciting side to workwear that is not generally talked about.” The show, which grew out of Begic’s own PhD research on clothing and utopian futures, is the museum’s first exploration into the world of functional clothing – and, as the Netherlands’ national museum and institute for architecture, design and digital culture, one would be hard-pressed to find a more appropriate home.

In situ, Begic’s focus has resulted in a show which traces workwear from its most acutely functional – a line-up of uniforms that, from Polish flying suits to kimono-like Japanese firefighter uniforms, showcases workwear’s protective origins – through to its utopian promise for political ideologies, its interpretation by artist and designers, and finally a section exploring the inherent sustainability to many of the methods that have crafted real workwear. With fashion commentators throwing around the term “workwear” with such enthusiasm in recent years – hoping it will stick to frankly below-par garments – this show resists platitudes to remind us of the true meaning of functional clothes.

That’s not to say fashion doesn’t play a role in Workwear, with Yohji Yamamoto tailoring and Helmut Lang’s iconic Astro moto suit among the garments gathered here. In one display, the links between workwear and beloved fashion items are made clear: displayed like a flat lay in a department store, we see a cross-section of Margiela tabis along with the Japanese slipper as used by Samurais, Dutch carved wooden clogs with Birkenstocks, and even a folded newspaper hat, once used to protect printmakers from splatters on the job. With this curation, Eldina wanted to issue a challenge to brands who simply lift from the aesthetics of workwear, to instead push it to a more interesting place of function. That is: why aren’t we making our clothes work more for us? “I always think, why is this not taken on more as design? We heat these enormous spaces, but we never really developed clothing that can heat your body as opposed to space. It's been explored, in the 1940s or 50s – pilot suits were made to be heated or even cooled. All these things have been done, but it’s interesting why there haven’t been more collaborations between science, and clothing design, in everyday life.”

Whether in the context of testing humans’ ability to survive, or even the far riskier endeavour of simply helping them to connect, Workwear broadens and deepens ideas of what our clothing can do. Below, Eldina spoke through some of the show’s most resonant, and rare, objects.

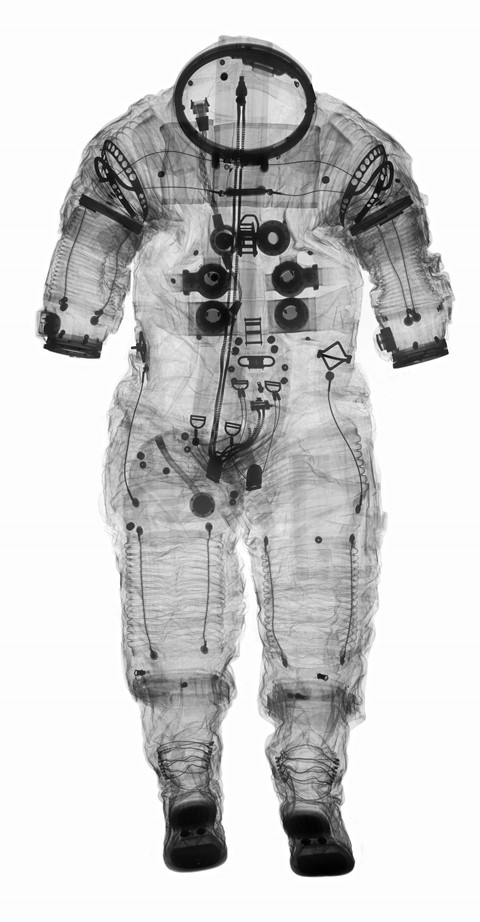

X-Ray Space Suit, NASA, 1960s

“Who wouldn’t want a spacesuit in an exhibition? There was no chance, however, because even at the Smithsonian, the most valuable item in their entire collection is their NASA spacesuit. But the X-ray is interesting in and of itself. They still use it as a kind of proof control, to check if there are any pins and suchlike left in the suit, which would be dangerous in flight. For us, by showing it as an X-ray on the mannequin, you can actually see lots of these technical details that you would otherwise miss. The spacesuits are all actually made by tailors who are sewing these things on sewing machines. It’s the most technologically advanced piece of clothing, and the most expensive – which makes sense but is also bizarre in terms of the usual glamorous associations of expensive clothing. Apparently, making a space suit costs about two million dollars.”

Iris de Leeuw, Space Suit, 1966-1967

“The general concept of the exhibition really hinges on ideas like connectivity. This is how this idea of connected suits came about. This is Iris de Leeuw’s suit, Seespak, that we also show with the certificate of authenticity that gives instructions for how it might work. The zip allows the legs to be zipped off and exchanged among wearers, which would break the taboo of touching intimate space close to the body. In recent years, the fragmentation of identities has become so intense, that it’s almost as if we’ve forgotten how to talk about connections, and how to bring people together. I wanted to talk about work which really unifies, and has elements that are almost like an antidote to fashion.”

Maria Blaisse, Flexicaps, 1985-1989, as seen at Issey Miyake

“Maria Blaisse is phenomenal. Originally I didn’t actually know much about her work, but I found an image of that hat, which is apparently where it all began for her: what she calls her forms. It’s a very simple principle, of using industrial material – like rubber from a rubber tyre – and vacuum-forming them. We got in touch and she insisted we come to her studio in Amsterdam and see what she does, which was fantastic. Because I thought this hat was a kind of product of collaboration between her and Issey Miyake, but the story is actually that she was wearing her Flexicap around New York in the 80s, he spotted her and then invited her to come to his studio to make them for his show. And she did that for several collections.”

Massimo Osti, Various Stone Island and CP Company Archive, 1980s

“Massimo Osti was a real innovator at the time, and it’s sad that many young people and designers don’t know much about him. He is the person who pioneered this kind of fusion of workwear, military clothing and streetwear. I don’t think anyone else really did it in such a radical way. But what was interesting about him was that he wasn’t like a fashion designer. He really was all about expanding innovation, not just in materials, but with a consideration of the human side: to improve what people wear, to protect them. He was experimenting so much with fabrics, set up his own screen printing and dyeing studio, and employed a chemical engineer to work with because he couldn't get the finishes of fabrics they wanted. He also owned an incredibly large archive of workwear himself: something like 40,000 pieces across two warehouses. He was working in a way that would require lots of compromise and lots of sacrifice, in terms of spending lots of time and resources, even if it wasn’t going to be very profitable.”

TuTa Suit, Thayaht, 1920s

“I could talk forever about the utopian section, which is relatively small, but was difficult to achieve because it brings together very rare pieces. This T-shaped suit by Ernesto Thayaht was called the TuTa, which is the first time that ‘overalls’ appears in Italian vocabulary, as it roughly translates as an ‘all-in-one.’ It began with this very socialist agenda, with the pattern published in the newspaper La Nazione so that anyone could copy it, and it was also unisex. Later, he starts selling patterns, so it moves away from that original message. Which tends to happen. Winston Churchill’s siren suit is very similar: designed based on bricklayers overalls, but then made for him in nice fabrics like velvet, or in pinstripes. It’s interesting, as though he wasn’t a socialist, at the time that really worked for him to unite the country. And in his memoirs, he says how this overall really made the public believe that he was one of them.”

Workwear is on show at Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam until 9 September 2023.