This article is taken from the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of AnOther Magazine:

On a busy November afternoon at Balthazar, New York’s enduring power-lunch spot, a chocolate-brown leather bag rests on the seat of one of its famous cherry-red booths. Resembling a suitcase, it’s named the Ana, its oversized horseshoe-shaped handle stamped with its maker’s gold moniker – Luar. The Ana is as regular a sight in downtown Manhattan as its owner – incidentally, also its designer – who sits beside it.

That is Raul Lopez, the label’s name is his own, inverted, since it’s a “true reflection of himself”. He is glamorous in layers of cream knit and own-brand mask sunglasses, and in a buoyant mood. Not only is it his 33rd birthday, but the night before he won the CFDA’s 2022 award for American Accessory Designer of the Year, in what seemed like a full-circle moment for a New York native who has largely operated on the fringes of the US fashion industry for more than 17 years. “I felt like it was a mistake or something,” he says in between sips of a hair-of-the-dog cocktail. “I thought it would be Brandon [Blackwood] or Telfar [Clemens] – they have more followers, you know?” He pauses. “I didn’t go to fashion school or anything, so it felt like getting my diploma.

Though it may have come as a surprise to Lopez, the win is just the icing on the cake of a breakout year for the designer, who has been enjoying both the explosion of that Ana bag and ecstatic praise for his Spring/Summer 2023 collection. Presented in Manhattan, at the Diller Scofidio + Renfro-designed cultural centre The Shed, the oversubscribed, standing-room-only show generated mayhem that led to the closure of the surrounding Hudson Yards streets. Fellow designers Clemens and Martine Rose embraced a crying Lopez when he came out for his final bow. Despite the scrum to get in – “These kids from NYU copied the QR code from the invitation and blasted the address” – and the show’s late-Sunday-night start in torrential rain, Lopez’s long-built community showed up in full force to support him. Just as they have by buying his work.

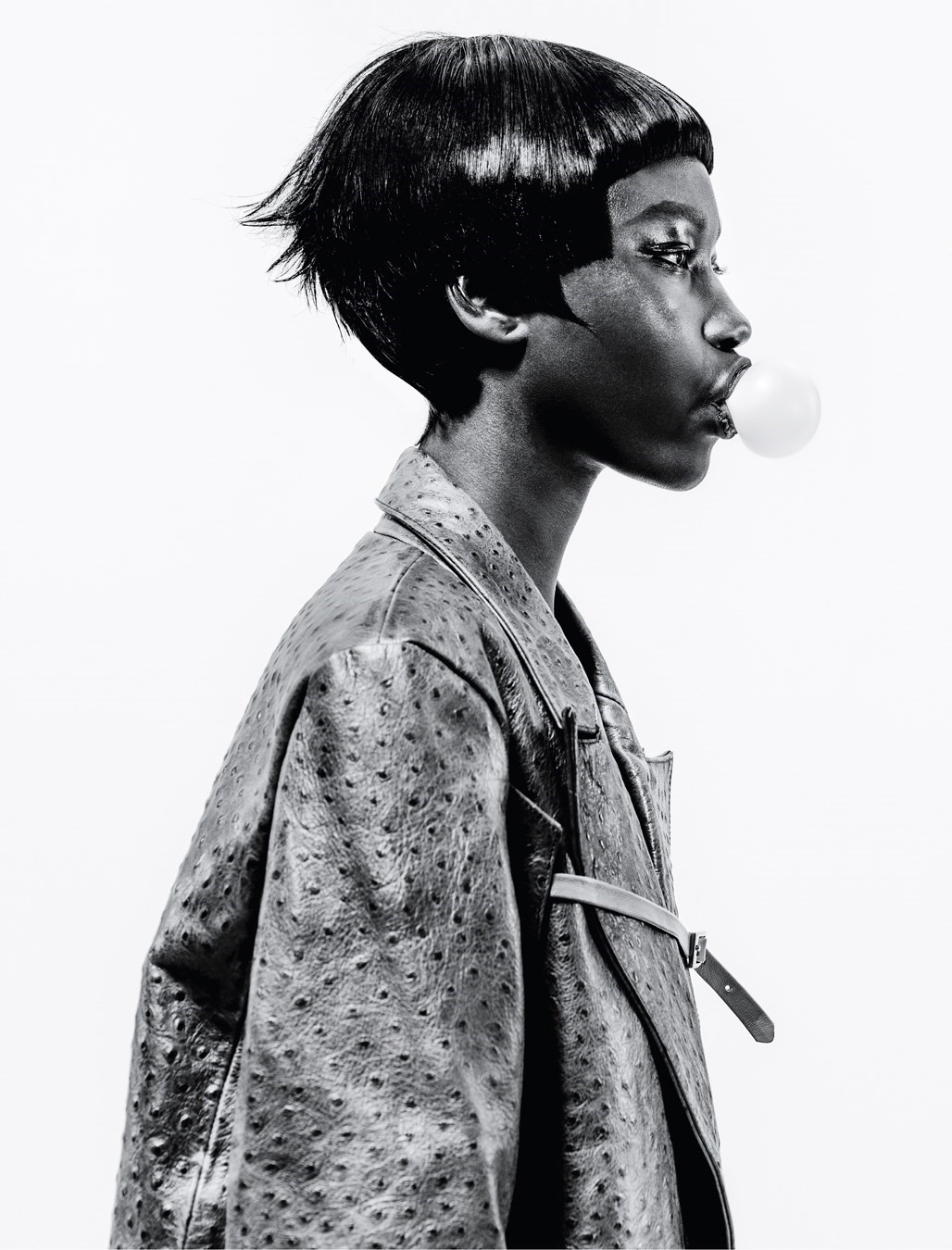

Entitled La Alta Gama, which translates as ‘high end’ in Lopez’s native Spanish, the collection was a reimagination of the designer’s Dominican heritage, punctuated by the long-fought-for American luxuries and knockoffs worn by the Brooklyn women of his youth. Look one of La Alta Gama establishes the template of the Luar woman: a khaki and navy long-sleeved, quarterback-shouldered top with a skirt ruched towards a crystal ‘L’ emblem at the pubis. Her swooped, gelled updo and Cazal-style sunglasses conjured the image of a New York go-getter – the kind of matriarch who raised him. Street smart and high-energy, with the electric guitar of Alejandra Guzmán’s Llama Por Favor booming in the background, the collection reimagined Nineties nylon sportswear – popular hand-me-downs inherited by family members as they arrived as immigrants from the islands – as pullovers and tailored trousers. “We’d have to make those nylon pieces work because they were all we could afford, even though it was so cold in the New York winters,” Lopez recalls. Oversized tailoring meant more than an aesthetic choice: “It didn’t matter what was too big. We really were just making it work.”

Indeed, the collection had meaning throughout. In its purest sense it felt the most Raul we’ve seen of Luar – the friendly confidant (he’s known to greet everyone with a familiar “Hey Sis!”) and New York stalwart who makes the city feel that bit more neighbourhood-like. “It’s funny, Shayne [Oliver, with whom he founded the label Hood By Air in 2005 and who has been a friend since the pair were in their late teens] has always told me I needed to embrace being Latina. To be more ‘cha-cha’. He would say, ‘Stop trying to be something you aren’t.’ I started to think, ‘The girls are right. Maybe I just need to really embody my true self.’”

Lopez’s childhood was spent in Los Sures, on the south side of Brooklyn’s Williamsburg, in the apartment building he lives in to this day. His father, who works in construction, used to be the building’s superintendent and his mother, now retired, was a seamstress. “[Williamsburg] was a dump,” Lopez says, frankly. “Nothing like now.” Having become one of New York City’s most gentrified areas, today the neighbourhood is full of chain stores and riverside loft apartments, but Lopez has stayed put. He still feels an affinity with the place he grew up in. “When I go to Washington Heights or the Bronx [the largest Dominican area in New York City] they don’t believe it’s so fancy now.

“When family came from the Dominican to New York with no money, all we could guarantee them was a jacket [for the cold weather], $20 and a job at the garment factories in SoHo. My grandmother, mother, sister, all the aunties had industrial machines at home, so they all knew how to sew.” That also unpacks his own formative understanding of garment construction.

Crime in the area was rampant and the female sex workers Lopez saw on his way to work were among his earliest inspirations. “We weren’t supposed to go down Kent Avenue because of all the prostitutes and crackheads,” Lopez says. “But I used to love it because all the girls looked fabulous, waiting to make a cheque out of the men working at the Domino sugar factories. They wore fringe, big pocketbooks, long jackets with nothing on underneath. The women dressed for the hustle and to provoke men. That has always stayed with me.”

[On leaving Hood By Air] “There was nothing wrong, I just wanted to tell my own story. It was bittersweet. Shayne was my sister and I kind of felt like I was betraying her, but I didn’t” – Raul Lopez

Lopez describes being robbed and beaten because of his sexuality during his adolescence – both within and outside the family home. “On the streets. My family, everybody. It was crazy. My brother used to line up dudes outside our apartment block to beat me up. You see this scar right here?” He points to a flaw just east of his left eye. “I got pistol-whipped and robbed for my Jacob & Co watch. At school I had tough skin – I would always want to fight. A teacher even held me back a year because I was gay. I saw him in Whole Foods recently with his wife and I let him have it.” Now, Lopez laughs.

By the time he got to high school, Lopez was, in his own words, “cosplaying as straight”, concealing his identity to survive. One of the few places he could be himself was Christopher Street, the location of the Stonewall Inn and the uprising of 1969. “It was the Times Square of the game. It’s where you wore your looks and got your life. If you met someone in a chatroom you’d go to Christopher Street. I didn’t even know all the history – I would see it from the West Side Highway on my way home from my grandmother’s in the Bronx.” Lopez talks of packing a bag of flamboyant clothes and changing on the F Train or in the station. “There’s no way I could leave the house like that! But it’s where I found all my tribes. It’s where I met Shayne, actually – blond mohawk, leopard leggings and a fringe top.” Lopez was enamoured but he didn’t want to admit it. “I was so shady.”

Lopez’s hustler mentality led him to create an ironing business in his building. “[It was] $10 a bag and I would do seven bags a day – I would earn $700 a week and I got tips too. Just ironing while I watched TV.” His own designs began to take shape then too: “Taking old JNCO jeans and Hanes tees and sewing things on. It’s why chopping things up is still in my DNA.”

While the late-night ballroom scene laid the foundations for firm friendships, Lopez bypassed the heavy drug use prevalent in its circles at the time. “I never did drugs and never have – the trauma of my uncle dying of Aids from sharing crack needles. Family members robbing their own – taking diapers, chains – just to get a hit, it scared me off. I just wanted to earn money, to start my label. And you know, we didn’t perfectly fit in downtown – the skaters and all those dudes – and we weren’t pure ballroom either. I think that’s why we wanted to create a brand for people who didn’t fit in.”

Hood By Air was born off the back of a set of Oliver’s initial designs. Starting out with T-shirts, the pair grew their label to become one of the Noughties’ most defining, albeit polarising, names in fashion. Hood By Air was equal parts future-forward and contemporaneously destructive – it set out to dismantle the industry’s status quo. “I was obsessed with future shit. I want to do everything for the future,” Lopez says now. In 2010, at the height of Hood By Air’s popularity, he left to start his own label. “There was nothing wrong, I just wanted to tell my own story. It was bittersweet. Shayne was my sister and I kind of felt like I was betraying her, but I didn’t – I wasn’t gonna go straight into it, I just wanted a break.”

Lopez did just that in 2011, when he relocated to the Dominican Republic to work on Luar Zepol (read it backwards), the first iteration of his brand. Posting pieces on Facebook – Instagram wasn’t a thing yet – Lopez used his mother as inspiration (“The best dressed woman I know, always giving glam”). Money came by way of an angel investor and friend of Lopez’s who put her personal funds into the company, but when she was no longer able to invest, Lopez “worked all night, then I would be at the factories in the garment district working on the collections all day and do it again”. There were peaks and valleys and Lopez closed the label in 2014. In 2017 he tried again, now calling his label just Luar, and became a CFDA Vogue Fashion Fund finalist the following year. The main prize went to Pyer Moss’s Kerby Jean-Raymond, propelling Lopez into a second, and more urgent, hiatus. “My mental health was suffering. I thought, ‘Let me take a step back.’ I needed to work out, ‘How do I run this brand where I can financially sustain myself?’ I needed to learn more of the business aspect, because I was approaching it as an artist.”

In the spirit of New York community, Jean-Raymond (another NYC-born and raised designer) introduced Lopez to his talent incubator, Your Friends in New York, launched with backing and support from Kering, to help him with the business operations, manufacturing and logistics of his label. Third time – and a bit of business acumen – was the charm. The Ana design, with its Sixties, mod-style handle and Eighties aesthetic, which he had been sitting on for a while, became the perfect low-cost, high-margin merchandise his fans and supporters could get behind. The bag now accounts for 60 per cent of the business and has been lovingly dubbed the Crown Heights Kelly to Telfar’s Bushwick Birkin.

Now Luar has five employees and the hustle is around the clock. “It’s hard to find a team you can trust,” Lopez says – but indicates it’s finally in place. “At the end of the day, you’re like, ‘This is my name, this is my money that I work hard for,’ but letting these people do shit for me is crazy. That’s my biggest accomplishment – learning how to delegate and let people wear my hat. I’m excited about the future now, my next collection, the continuation of my story. Chapter three.”

Hair: Lucas Wilson at Day One using ORIBE. Make-up: Frankie Boyd at Streeters using VALENTINO BEAUTY. Manicure: Nori Yamanaka at See Management using CHANEL. Models: Diana Achan at Fusion Models and Anyiang Yak at The Society Management. Casting: Bert Martirosyan. Photographic assistant: Amelia Hammond. Styling assistants: Meena Jannah and Jada Pierre. Production: CLM

This story features in the Spring/Summer 2023 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale now. Order here.