Its premise is simple, but the lore is storied. Every year at Central Saint Martins, first-year fashion design students are asked to make a single look entirely out of white fabric. First-year fashion communication and promotion students respond by creating a show concept, a lookbook, and host a select number of attendees to watch the show on campus – while the rest of the university’s students nestle into various nooks and crannies in the four-storey glass studio blocks, or crowd the overhead bridges, in attempts to catch a glimpse at some inevitable runway theatrics. It’s a sort of initiation project that’s lasted more than two decades, but this time with a slight rebrand: instead of plain white fabric, all the textiles are made from waste and are recyclable, and instead of the White Show, it’s been renamed the Reset Show.

Part of the reason it’s so exclusive is because students are still in their incubation period, yet to complete even their first term (despite a certain Vogue critic known to regularly gatecrash). It’s a chance for many students to showcase their designs for what could be the first time publicly, take stock of the goings-on behind the scenes of a fashion show, and square up the coursemates they’ll be thrown into the industry with. 166 students make up this year’s first-year class of design, yet amidst the shouty melodramatics, stars do emerge. Christened Ready, Set by fashion communication students, this year’s Reset Show adopted a sporty theme. Staged in the campus’s central corridor, an opening troupe of performers limbered up and stretched out to the rumbling soundtrack of stadium applause, before a 30-minute show ripped through the university’s echoey hall.

It’s a challenging time to be a fashion student, and perhaps the necessity to ‘make it’ seems more like a 100-metre sprint than ever. Imbued with financial and existential dread, and a worsening political situation, fashion can be regarded as trivial, superfluous. Handed out before the show was a pamphlet informing about UAL’s complicity in Gaza, instead of an expected press release. It’s part and parcel with the university’s radical approach to education, encouraging introspection and critical thinking, as well as providing the technical skills needed for a career in design.

Below, AnOther speaks with five first-year BA fashion design students who presented their work, each look a symbol of a fascinating backstory laid bare in textile and design. Here, they unpick the complex references behind them.

Ben Brody, 19, BA Fashion Menswear

“My look for the Reset Show was an ode to architect costume parties where architects come dressed as the building they designed themselves. As someone who originally wanted to be in architecture, I saw this as an opportunity to exaggerate my love for buildings and the spaces that they radiate. I stepped back from being a ‘fashion designer’ and went about this project from the viewpoint of how architects design their buildings. I discovered similarities between blueprint drawings and traditional pattern cutting and found myself with a plethora of geometric shapes all hand-cut and measured.

“My perspective on fashion design is very unconventional. I don’t necessarily see a body when I’m working, rather what a final silhouette could look like. I try to create shapes that are familiar to my ethos, but almost unheard of to the industry – such as a wearable house. When in high school [in Texas] I used to visit modern-contemporary architecture and reform my design identity around the use of minimalist approach and brutalist ideas. This led me into a lore of what modernism means, and how I could use it in my everyday practice.”

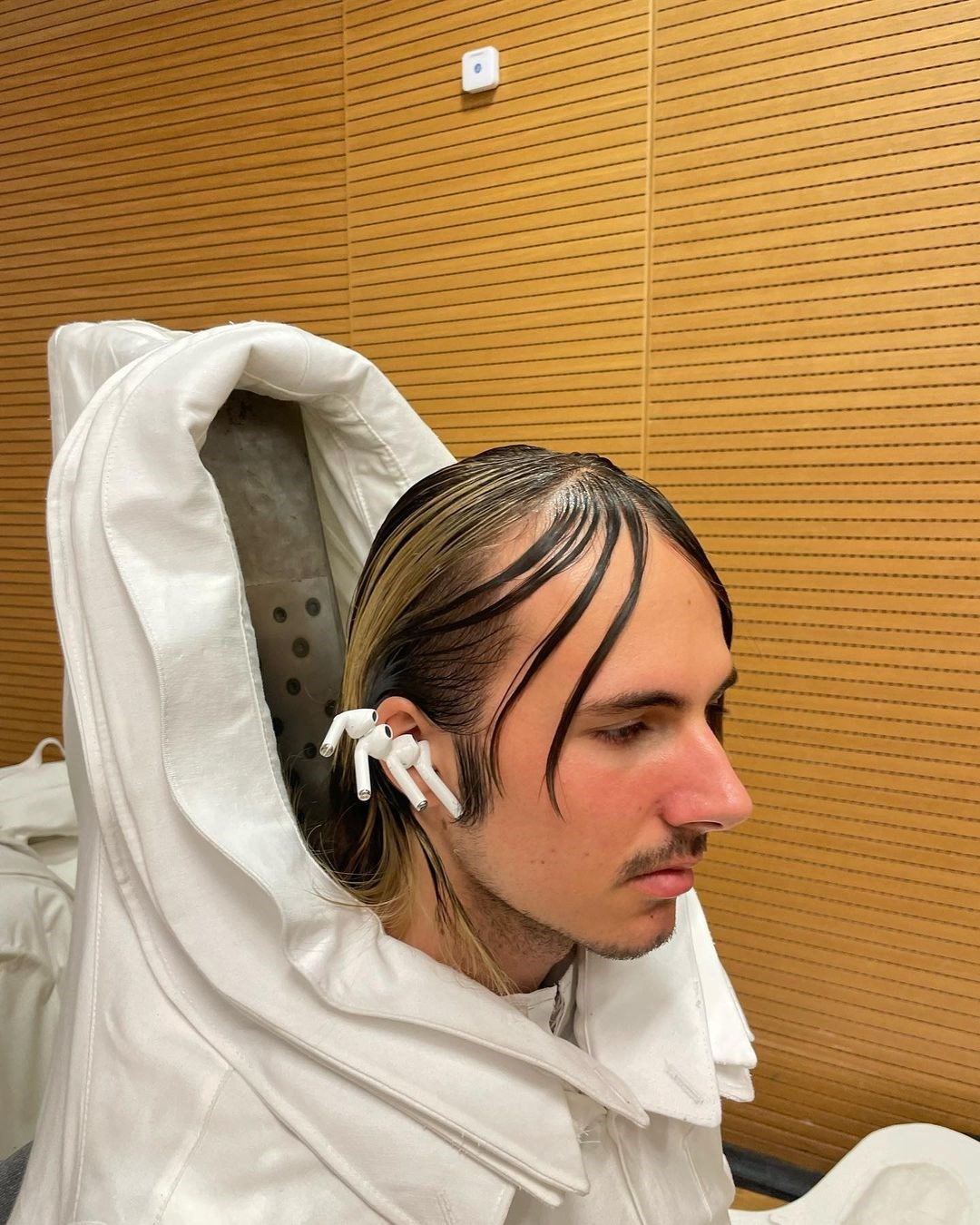

Neil Zhao, 22, BA Fashion Print

“I wanted to research the industry I am about to enter into: how the space that fashion takes up today is a reflection of some of the absurdity of our time. Where on the top, big fashion houses produce Resort and pre-collections in addition to keeping up with fashion weeks, and at the lower end, fast fashion chains produce endless amounts of ten-pound white shirts. All the while, us fashion students are working day and night because we are sold this dream that ‘one day you might also make it.’

“I explored the idea of layering in a meaningless way with the same garment. My look consists of four oversized blazer jackets and sixteen white shirts, four pairs of AirPods and four pairs of socks and a sewing machine bag. I see clothes as a way of communication. I am interested in semiotics. A lot of my work utilises what the mind already knows – wardrobe staples like blazer jackets, button-down shirts. In that way, I try to tell my story with a familiar language.”

Eleonora Razzoli, 21, BA Fashion Design: Communication

“I titled this project After the Flood. It revolves around the flooding of the Arno that happened in Florence on November 4th 1966, leaving the city in a sea of mud. Seeing the images of the flood left me in a state of uncanny, seeing the familiar streets that I walked so many times being completely submerged in mud and chaos were now unfamiliar to me. There’s this saying in Italian that you ‘marry the city you were born into’, therefore I imagined this woman, walking the muddy streets with hope in her eyes, trying to remember how it was before – mourning the numerous lives lost, the families and the enormous loss of books and art that generations like mine will never be able to lay our eyes on.

“I grew up in a household where art has always been appreciated, in particular modern contemporary Italian art, and from an early age I was taught to see and question what I was looking at. Academically speaking, I intensely studied the history of art during my five years of high school, but generally being in Florence unconsciously has influenced me to the bone. I’m very research-driven. [In the future] I’m going to need a space that will allow me to continue to work in a detailed and artisanal way, carefully developing my research and storytelling.”

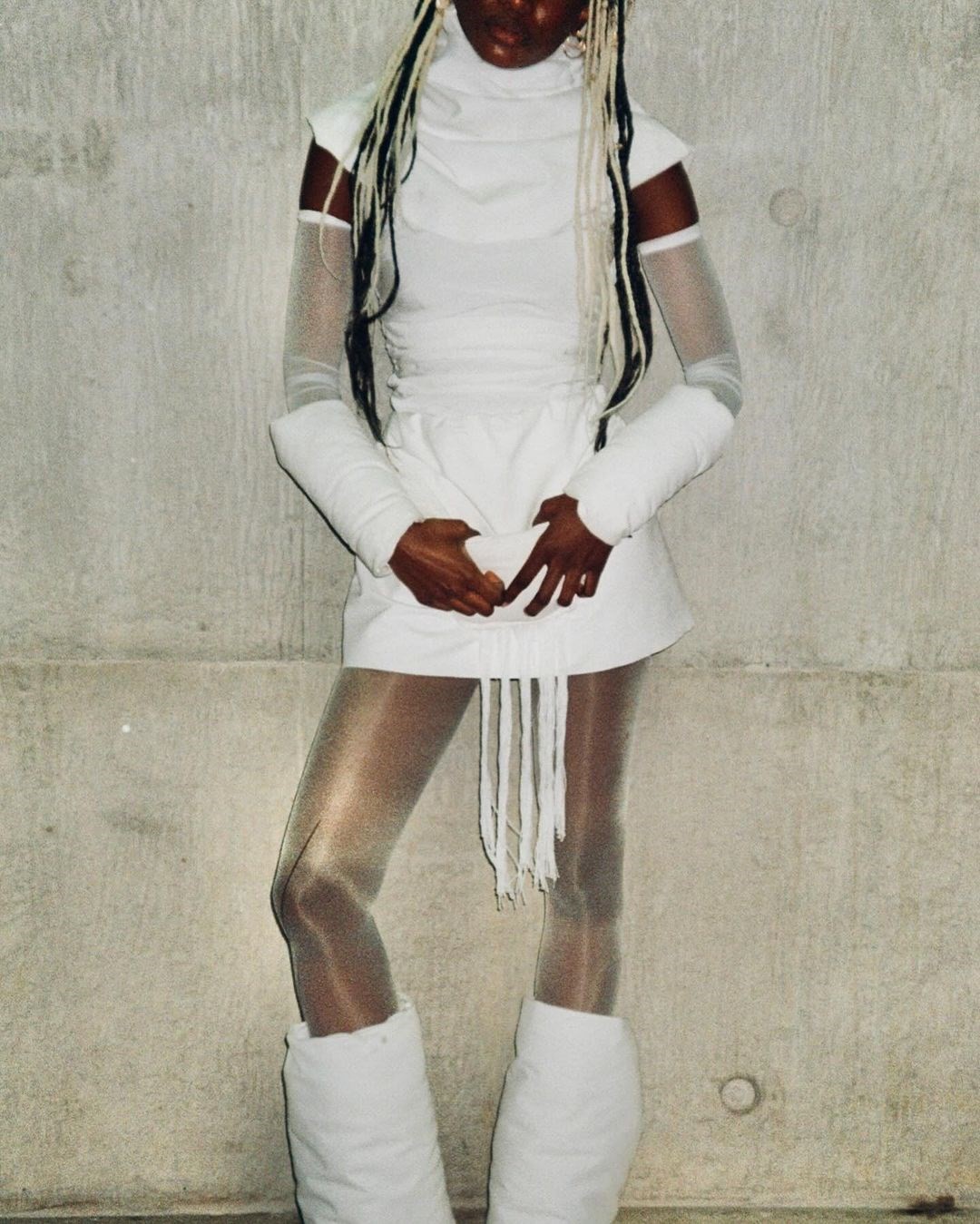

Oluwalaní Jegede, 19, BA Fashion Womenswear

“I was never really taught about Nigeria’s history, beyond that we used to belong to the British. I didn’t know about the kingdoms that existed before that, and what our society was like. The few images and objects that remain are in large the only remnants of our culture before colonisation, like images shot in West Africa sometimes more than 100 years ago. I spend a lot of time studying them, and even more time questioning my obsession. Body adornments visually blend into skin becoming just subtle indentations or protrusions, the adornments were the clothes. I explored this concerning distorted body proportions I found in carved Yoruba figures, shifting the focus to the body. I found that a lot of the images, with wooden carvings and masks, seemed so foreign that they felt either ancient or futuristic, nevertheless out of reach, difficult to understand and from a different world entirely.

“I grew up in Abuja, Nigeria. I was born in the US, and I’ve gone to school in the UK since I was around thirteen. I’m familiar with very different types of society, and different strains of blackness from living in different countries – they’re entirely different worlds. There’s a glass ceiling where, as a Nigerian, I didn’t feel that anything Nigerian was worth talking about. I think there’s aspiration in being Nigerian, from watching everything happening in the West from the sidelines, because it’s not including you. This is something I’m trying to channel, to create the feeling of seeing contemporary in a way that you aren’t connected to, and that’s something I remember every time I go back home and then come back here.”

Selina Dreijer, 20, BA Fashion Knitwear

“My work revolves mostly around emotion and the human psyche, and for some reason, my projects always relate back to my mom. I was thinking about generational trauma, and how pressure evolves. My grandfather was a big factor in this. I found out all of his stuff got taken away by the Chinese government during the Cultural Revolution, and the only thing that was left of him were the letters he wrote to my grandmother. The letters were such an important artefact that created a new perspective of him and my mother. How do we get to know a family member that we’ve never known, but had such a big impact on your upbringing?

“For me, fashion design is the opportunity to reformulate functionality through innovative thinking and storytelling. It is some form of therapy to me as I see myself writing somewhat ‘love letters’ to my past self through my concepts. I think what I find most important is to convey the emotions and the story to the audience and wearer through silhouette and texture. I like to study the human psyche and create abstract shapes that I can use for my development. Before I finalise my design, I do lots of sampling so I can make sure the intimacy of my concept is translated through my final design.”