Duran Lantink is ensconced in a kitchen-slash-toilet space in his Amsterdam studio, sporadically flailing his arms in the air to prompt the motion sensor lights overhead to flicker back to life. It’s an un-chic set up for Paris Fashion Week’s new darling. “The ambition is to move to Paris, but it takes time,” he says with a soft Dutch accent and an optimistic, but anxious, smile. “Locations, budgets – they’re all difficult, but we’ll figure it out.”

This time last year he showed in Paris for the first time, then returned in October for a breakthrough show of upcycled globular forms that catapulted him into fashion’s collective consciousness. His so-called “bubble” ensembles became a stylists’ favourite overnight, ubiquitous in the glossy pages of this season’s fashion magazines – but Lantink is learning the hard way that exposure doesn’t necessarily pay the bills. When we speak, it’s a little over a week until he presents his Autumn/Winter 2024 collection, and he’s heading to Paris early to present his work to the jury for the LVMH Prize, where he finds himself a finalist for the second time. So perhaps his nerves are justified.

Professionally, Lantink has come a long way since he was crafting clothes for his Barbies as a six-year-old, yet the same processes endure. He’s slicing up found materials, mixing and collaging them, stuffing them with padding and shrinking them down. He’s remaking the old into something entirely new. “I always wanted to do something with clothing. Being queer or gay at a young age, you already feel like you belong to another world. A world that isn’t really there yet,” he reflects, “so I started experimenting with clothes. Being being hardcore. Piercing my ears. Dyeing my hair. Wearing my mum’s dresses to school.”

He pared back his rebel ethos for Spring/Summer 2024, moving away from clothing collage and more towards exploring form, and in that transition, his surrealist handwriting felt crystal clear. “Showing in Paris made me feel I wanted to set the boundary higher,” he says of his shift in focus. “It’s what fashion for me is about, it’s the holy grail.” Titled Duran-Ski, his Autumn/Winter 2024 collection revives the clothing mash-ups of his earlier days and brings his beloved, blobby shapes into a new context. “Working with seasons is a new thing for me, so I’ve been questioning the simplest things: What is winter about? And what is winter in luxury? Skiing. For me, it’s ski,” he says. Its starting point stems more from some logical equation than a deeply personal theme. “I love winter sports, but I haven’t been in years. I don’t have the time, and I don’t have the money.”

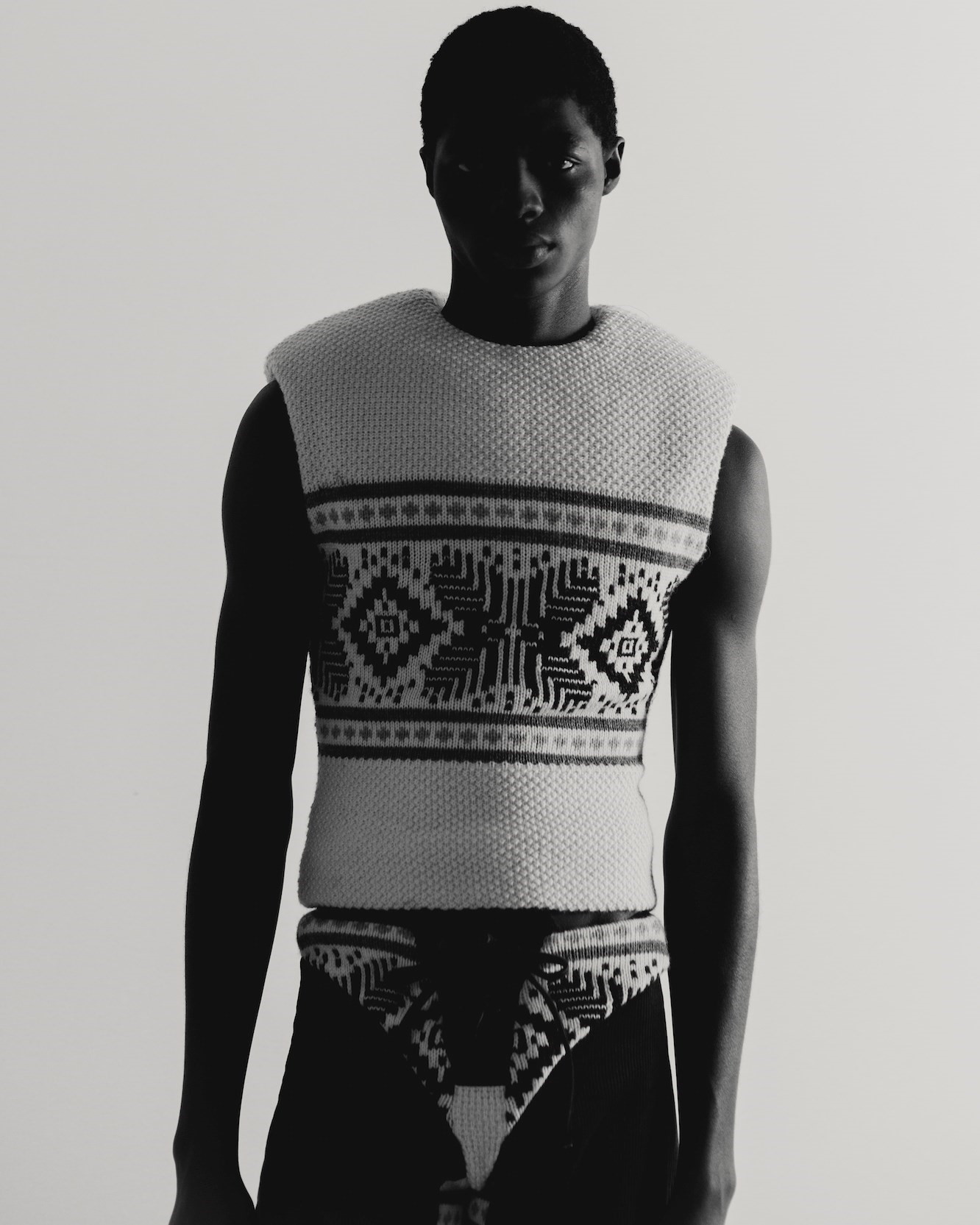

Opening the show, Rianne Van Rompaey struts out in a cosy wine-red roll-neck sweater dress, padded from the upper bust to the shoulder like some ancient soldier, paired with some thigh-high stockings inspired by those worn by Dutch firemen in the 1970s. Another look sees a Christmassy knitted jumper liquified into a vest and padded with foam, sliced diagonally to reveal its inches-deep thickness and rigidity in motion, and worn with flesh-baring matchy-matchy cushioned pants. Elsewhere, a snowsuit is enlarged with an 80s-style shoulder, nipped in at the waist and cropped into briefs – its original Helly Hansen logo is left stitched at the chest. Vintage Loewe and Maison Margiela form the basis for Lantink’s new shapes, reformed into Hulk-shouldered leather bombers and itsy-bitsy hot pants.

Lantink is, and will always be, an eco-conscious designer – it’s part of his DNA as a maker. “I don’t have the luxury of starting with an entire moodboard. I start with a clothing rack of vintage pieces, and we start directly trying to figure out what to do with it,” he explains. “Almost all my clothes start with an existing piece, and from there, we start building around it, experimenting. In the end, we form a collection.”

But the world Lantink is building is growing beyond the ‘sustainable designer’ epithet – had each piece not been upcycled, they would still fizz with that same sense of radical wonderment. Circularity is now a bullet point in the manifesto as opposed to their main brand signifier. Just about everything the designer makes had, too, already been made from something else – not from hessian sacks or off-cuts, but from real discarded clothes. Yet, still, Lantink refuses to let the clothes he remixes become their last iteration. “We have the alteration button on our website. Let’s say you buy a coat from us, and in a year, a year and a half, or longer, it’s ripped, or you don’t like it anymore. You can book a consultancy with my team, and they start transforming the piece into a dress or a pair of pants. We charge for it, obviously. We’re not a charity,” he says. “But it’s a good way to know where your babies are – to know where those precious little things go.” By virtue of its labour of love, the label drops a one-of-a-kind item on his website twice a week, and as a certificate of ownership, each item is sold with a contract validated with a smear of his own blood.

Lantink’s approach to circularity is certainly several steps in the future, but at fashion school in Antwerp his melding of pre-existing designer pieces was branded as lazy. “They’d say ‘it’s more [a] job of a stylist rather than a designer’. But I didn’t really give a fuck.” When Lantink enrolled in a Master’s degree at The Sandberg Institute, he felt the world’s approach to regenerative fashion moving in the right direction. Melding with his eco-optimism and sense of humour (many thought it sacrilege to cut up a Dior and a Chanel bag, then haphazardly stick them together), his designs have a buzzed, avant-garde mischief to them. But now in their globular forms, proposed to an industry that’s obsessed with slimming down, how many buyers are going to be brave enough to bulk up?

“I feel great about what I’m doing, and it goes further than only the aesthetic. It’s trying to find a new way of dressing. I would love to see a regular person in a bubble top going to the supermarket,” he smiles, then pauses in thought. “I don’t know how realistic it is.” The Duran Lantink wearer would surely look fantastic in their puffer minidress or hot pants on the Alpine slopes, but it’s early days yet – his cult of puffed-up rebels are still yet to emerge. “I love that my pieces are being put into magazines, but I don’t believe that that’s where it ends. It needs to take that step further and it needs to go into the world,” he adds. “I don’t think that makes me a radical. I think it makes me a romantic.”