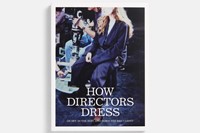

A new book from A24, How Directors Dress, explores the connection between the clothes they wear and the roles they play, both on and off set

Directors wear many hats in the ecosystem of a film set, responsible for both enacting their vision and cohering the crew. But as A24’s new publication How Directors Dress unpacks, in depth and in anecdote, there is a clear connection between how they dress and the roles they play both on and off set. “By talking about garments, we can cut through the usual Hollywood language of legends and icons,” writes Charlie Porter, of What Artists Wear, in his introduction, “The clothing worn by a director is so personal and holds such an intimate physical space, that it has a great deal to tells us, if we let the clothes themselves do the talking.”

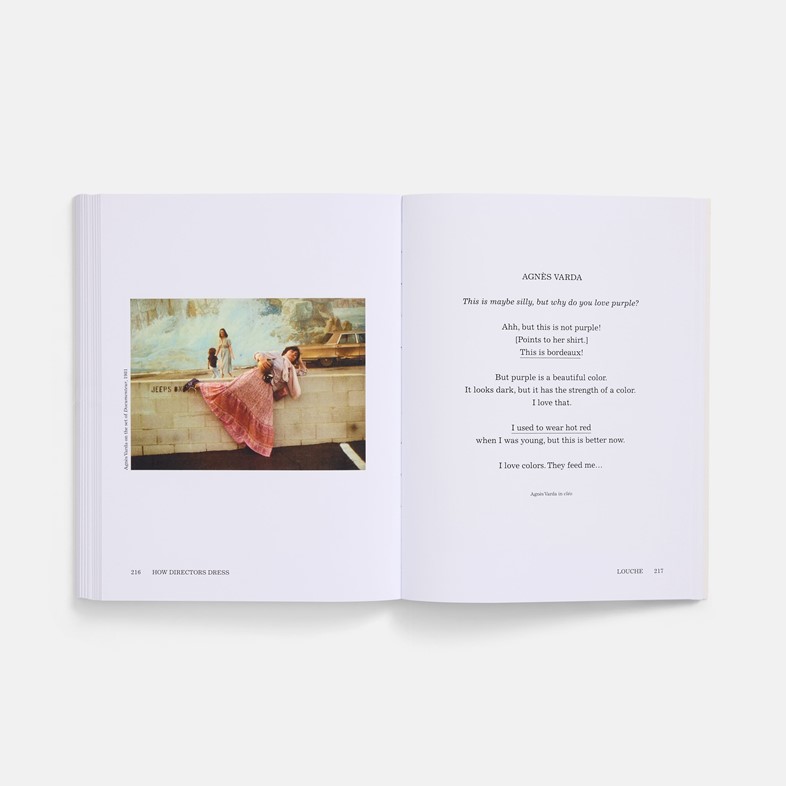

A director’s dress code has generally been embraced as lite off-duty sartorial inspiration, à la AnOther cover star Sofia Coppola, or funny industry fodder, like Steven Spielberg’s love for trucker hats. But a new crop of social media profiles – led by Hagop Kourounian’s brilliant Instagram account @directorfits – are dedicated to pinpointing what exactly cult-favourite directors wear during filmmaking. How Directors Dress builds upon this premise (Kourounian is a consultant on the book, along with Porter and Jon Dieringer, of Screen Slate) to question larger narratives of filmmaking: “Who gets to make films? Who gets shut out? How does a director deal with power on set, particularly when they are disenfranchised in everyday life?”

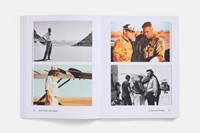

If popular stereotyping paints the director as a chain-smoking, barking auteur figure, the reality couldn’t be more different: most are in the trenches of their vision alongside the actors – and so are dressed for action accordingly. (Although many directors are still known to love smoking, as artist Brad Phillips writes in his essay for the book, Smoking on Set.) Through five chapters – covering themes from “workwear” to “louche” – which are considered by some of fashion’s most well-regarded journalists, such as Rachel Tashjian, AnOther contributing editor Claire Marie Healy, and Lauren Sherman, the book breaks down the logic behind director’s wardrobes. As the director-favourite designer Yohji Yamamoto – who famously created a suit jacket and pants with 15 pockets for Wim Wenders so that he didn’t have to carry luggage – neatly points out: “The first element directors think about is shooting their film. Not how to dress. How to work.”

The common stake seaming each theme together is the need for directors to be somewhat “invisible” on set. “You’re trying to enter a world you’ve created and be an observer within it,” explains Joanna Hogg, “You want to bring out the best from other people – not be the focus of attention yourself.” Some dress to work as efficiently as possible within the surrounding environment – contributing writer Adam Wray points to “the keffiyeh, biker gloves, and ski goggles Kathryn Bigelow wore when shooting The Hurt Locker (2008) in the Jordanian desert.” Others dress in character, like Ron Howard who spent four hours being made up exactly as Jim Carrey had to each day for his starring role in How The Grinch Stole Christmas (2000). Howard’s gesture was “comic yet sincerely empathetic, a way to utilise, and also subvert, his directorial position,” analyses Caitlin Quinlan in her essay Dressing in Character. “In dressing like his character, Howard plays with the hierarchies of the set and levels the space.”

Yet this sense of discreteness and practicality in how a director dresses need not always come at the expense of style. As Healy observes in her essay Buttoned Up, a dive into directors like Federico Fellini and David Lynch who have coopted the timeless button-up shirt as their signature style, “a uniform becomes more necessary as moviemaking becomes a life.” For Sofia Coppola, her personal uniform of tailored button-ups from the legendary Parisian men’s shirtmaker Charvet, provides a sense of control, of consistency amongst the chaos of filmmaking – "I like to have a bunch when I’m shooting so that I don’t have to think about what I’m wearing.” When it comes to the red carpet, Hogg similarly has a uniform: “a Balenciaga jacket I’ve worn since 2008, which I call my lucky jacket. It’s been worn so many times that I don’t even think about it anymore.”

How We Dress is illustrated by some 200 images of directors both on and off set, providing a rare insight into the physicality and personality of filmmaking. But in many ways, the images simply show “that they could be one of us, telling our stories, as author, narrator, and character, reflected back to us, on the screen,” says Porter. Or, as Hogg so perfectly surmises in her foreword for the book: “I am still searching for what I want to wear to work. And that means I’m still searching for who I am.”

How Directors Dress is published by A24, and is out now.