Tightrope walkers teetered over the labels’ collaborative catwalk in Tashkent – here, Jenia Kim tells AnOther about finding a more metaphorical ‘harmony and balance’ in the Uzbek capital

“Tightrope artists always seem on the verge of falling,” muses Jenia Kim, founder of the Uzbekistan-based label J.Kim. Yet, she adds, the act requires considerable strength – the apparent vulnerability of stepping out over empty space conceals “great skill, agility and fortitude”. It’s a delicate balance, and it serves as a central metaphor for the brand’s new collection in collaboration with Anton Belinskiy. For them, the Uzbek art of Darbozi tightrope walking became a symbol, Kim explains, of the balance “between strength and vulnerability, between Anton and myself, between different perspectives and views”.

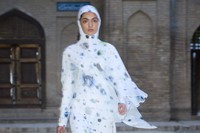

On an overcast day in May, this symbol came to life in the tranquil courtyard of Tashkent’s Abul Kasim Madrasa, where literal tightrope walkers – from The Wandering Circus of Central Asia – plied their trade over the debut J.Kim x Anton Belinskiy catwalk. Beneath these teetering bodies, a parade of models showcased the new collection, which channelled the circus theme (see: conical hats and multicoloured flag motifs) alongside multilayered takes on J.Kim’s signature petal cutouts and nods to Uzbekistan’s traditional culture.

Admittedly, ‘traditional’ is a complex term in Tashkent, the Uzbek capital. The city’s history is defined by radical upheavals, from its destruction by Genghis Khan in the 13th century, to its revival as a central hub on the Silk Road, to decades of Soviet rule. Today, as the most populous city in Central Asia, it wears the evidence of these revolutions on its sleeve. Mansions decorated with traditional Uzbek craftsmanship sit alongside towering brutalist buildings and Islamic architecture. All of this is linked together by an ornate, Soviet-style metro system: domed ceilings, themed murals, and multicoloured tiles.

Against the backdrop of this multicultural mixing pot, J.Kim’s studio is an outlier. Located off an unassuming courtyard, the space is bright, white, and airy, lacking the usual technicolour embellishments. Instead, the city’s character can be found in the moodboards that adorn the walls in Kim’s workspace, which are layered with local iconography: wheels of bread, rows of gold teeth, and swatches of bekasam. Then, of course, there’s the clothes in the latest collection Tightrope of Friendship, which marry local dress codes with oversized silhouettes and photographic prints lifted straight out of Belinskiy’s wheelhouse.

Kim says that “most of the collection was inspired by life in Tashkent,” where both designers lived and worked for the duration of the design process. (Typically, Belinskiy spends time between Paris and Kyiv, where he was born and raised. Kim was born to a Koryo-saram, or Soviet-Korean family in Uzbekistan.) Here, ‘inspiration’ means playing with the fashions of the Uzbek capital, from striped silks and swathes of gems, to the garments themselves: sleek head coverings and trousers layered with skirts, reimagined in J.Kim’s striking ‘Lazzat’ silhouette. But it also involved a more abstract interpretation of the city’s sights and sounds.

The collection’s accessories, for example, take direct inspiration from the charms, rosaries, and air fresheners that hang from taxis’ rear-view mirrors. An abundance of Chevrolets – which are almost ubiquitous in Tashkent, due to a local factory and high import rates – is reflected in prints of cars and car headlights, which are pushed to abstraction on silky shirting.

This brings us back to the setting of the show: the Abul Kasim Madrasa. While billowing flags printed with slogans of peace nodded to wider global concerns, the building itself was selected with deeply personal connections in mind. “It was important for us to create a peaceful environment that would convey feelings of harmony and balance within oneself,” Kim explains. “And this madrasah has always calmed me. It is an island of peace.”

It’s also a place with a heavy emphasis on craft, where male artisans gather to work on their creations and – in Kim’s own words – “seem to enter a state of meditation through their craft”. As a stage for J.Kim and Anton Belinskiy, it raises a number of dualities: between the personal and the political, the past and the future, the playful and serious, different cultures and creatives, and states of mind. In the end, everything comes back to balance, that unifying blend of strength and vulnerability. This, as J.Kim says, serves as the basis for all humanity’s “profound connections”, even (or especially) in these precarious times.