What is the purpose of haute couture? In the past, it rang in fashion’s shifts, a dynamic engine of change and constant renewal that shaped the dress of princesses to paupers. But the egalitarian appeal of ready-to-wear changed all that – why buy a reflection of a designer dress when you could get the real, talismanic thing? Couture became the ancien régime, a bloated and bygone system, a 21st-century anachronism. It continues to dress people today – but houses boast about adding two or three clients to their roster, and a couture dress is a bestseller if it shifts six versions. Of course, many clients pay more for there only to be one: theirs. It’s not about the many, but the chosen few.

The way couture does still function, however, is as a showcase for craft and creativity, a glorious baroque frame for the genius of a fashion designer, where budgets are limitless and vision uncompromised. In cinema, we have auteurs – in fashion, couturiers. It’s where a creative’s perspective can be truly unleashed. That was certainly the perspective Alessandro Michele took for his first Valentino haute couture show, and his first foray into couture full-stop. Of course, Michele’s aesthetic is perceived as couture-adjacent, with its glorification of embellishment and rich fabrics and its championing of the individual. They’re all traits we see as distinctly couture. But its methodologies are specific, different to ready-to-wear – outfits built by hand, progressed gradually over time and with a compression of knowledge and blood, sweat and tears into extraordinary single looks.

‘Cinematic’ was the word Michele used to describe his vision, a few days before his debut. You didn’t really understand what that meant until you entered the cavernous space of the Palais Brongniart to staggered stadium seating facing a ruched curtain straight out of old Hollywood. His show was titled Vertigineux, and Michele translated that as a breathtaking dizziness elicited by being able to create couture, a mind boggled by its capabilities and seemingly limitless possibilities. So, on that stage, he showed 48 different characters in wildly differing costumes, from silver sequinned armour, to vastly-crinolined Visconti ballgowns, to sleek Merry Widow mourning dress. Each outfit was accompanied by a litany of words, printed in a vast script on each seat and scrolling like a stock market ticker behind (the Brongniart was the Paris stock exchange under Napoleon, so it’s not entirely inappropriate), delineating the themes and inspirations behind each, as well as techniques and hundreds of thousands of hours of work crammed into their creation. In a word, it was all very vertigineux.

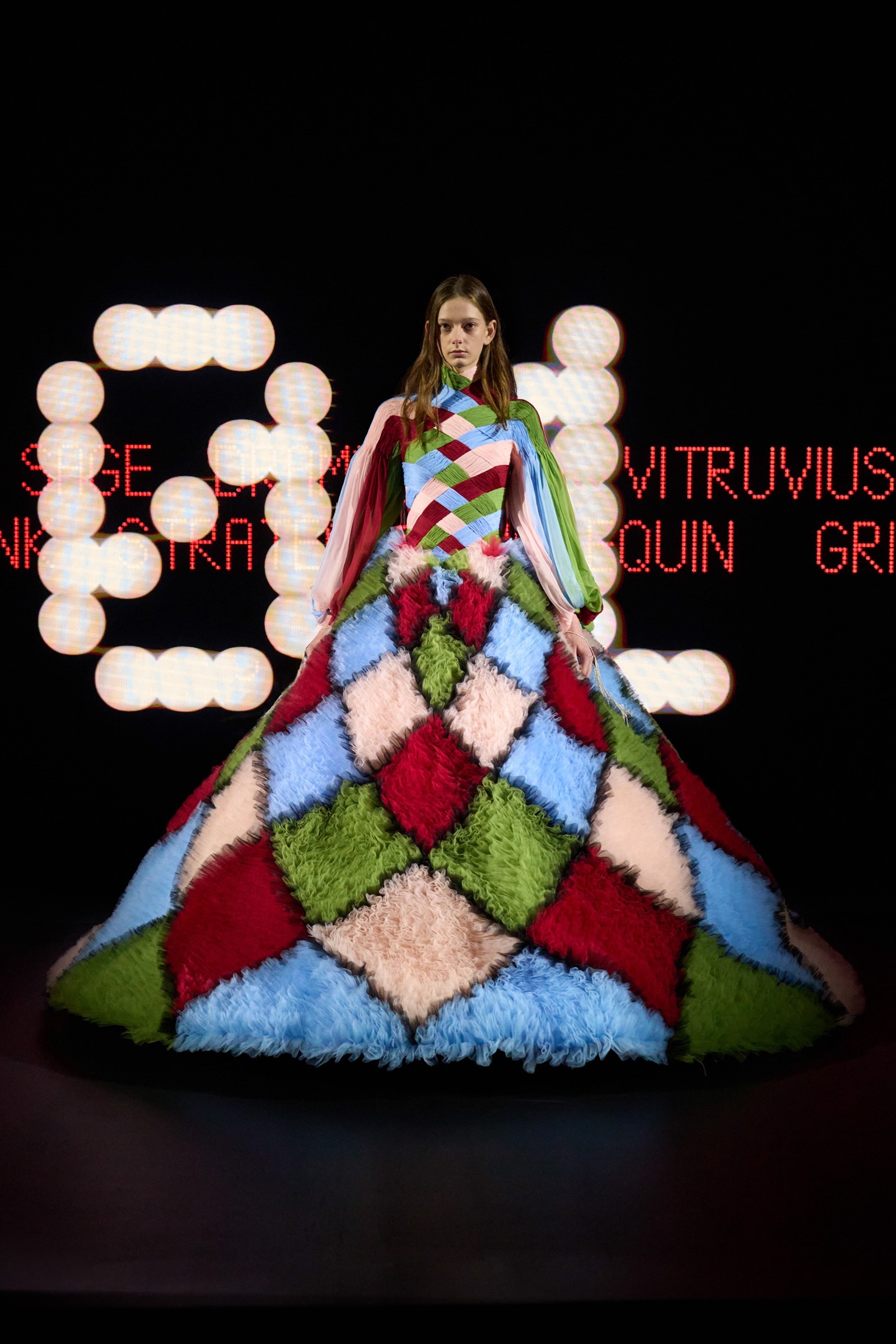

Many – if not all – were Valentino-coded, referential to almost seven decades of house history, techniques and themes. The open harlequin look came from an original from 1992; there was a red ruffled dress featured in a 1977 Valentino advertisement by Deborah Turbeville, here reproduced almost identically, bar the scale of the skirt, which was a literal and figurative big story throughout, swelling to Scarlett O’Hara proportions (who seems to be something of a heroine of the season – see Schiaparelli’s waists too).

“Mr Valentino’s obsessions have become my obsessions,” Michele stated. The ideals of beauty of these two are, often, wildly different: Mr Valentino is pushing 93 this year, so understandably his views are somewhat more conservative than Michele’s all-embracing, binary-smashing perspective. Yet somehow a common ground was found between the two – a love of operatic drama being one.

Valentino under Michele has scaled back its couture shows, to just one big bang of a statement every January. It also reminded you of another idea of couture, one that began to be proposed in the 1980s – couture as advertising, as pure projected image. Pierre Bergé, the financial Svengali behind the success of Yves Saint Laurent, once described the couture as “our advertising budget.” And these weren’t Valentino clothes engineered to the real, pampered lives of the mega-rich. Rather, they were propositions and evocations of fantasies, dreams made flesh. Fair enough, they weren’t modern. But is couture modern? Or is it a living link back to the extravagance of the past, with a space for it to propose something bigger and bolder, to provoke and excite? Certainly, Michele’s Valentino got everyone talking. “If you play it safe, there’s no buzz,” was something Valentino’s partner and financial brain Giancarlo Giammetti once said about the house’s couture. It seems Michele is top for taking risks. And that is actually very Valentino.