This story is taken from the Spring/Summer 2025 issue of AnOther Magazine:

Cartier is probably the most famous jewellery company in the world. That’s because its name means more than just diamonds and pearls – it’s part of history. Established in 1847, the house had only been in business a year when the July Monarchy was deposed in France’s February Revolution; the foundation of Napoleon III’s Second Empire came in 1852, barely five years in. There were also two world wars – by the first, Cartier’s operations had already spread to New York and London, and during the second, General Charles de Gaulle used Cartier’s London headquarters as an enlistment centre for the Free French Forces. Cartier nearly opened to service the profligate Romanov court of St Petersburg in the early 20th century but decided, presciently, not to permanently set up business in Russia. It did supply, of course – by 1910 it had a royal warrant from Tsar Nicholas II, alongside one from the King of Siam, and a position as jeweller to multiple maharajahs. King Edward VII coined the epithet “the jeweller of kings and the king of jewellers” and awarded a royal warrant to Cartier in 1904. He obviously knew what he was talking about.

Stories abound. How about the fact that, in 1917, the American businessman Morton F Plant sold his townhouse at 653 Fifth Avenue, New York, to the Cartier family for $100 and a double-strand necklace of 128 flawless, perfectly matched natural pearls to gift to his wife, Mae? That sounds like something out of One Thousand and One Nights, except for the decidedly modern detail that the necklace was then worth a cool million bucks (more than £20 million today), and that both sides thought they were getting a bargain. That address remains the site of Cartier’s New York flagship today. In 1920, Jean Cocteau described Cartier as “a subtle magician, who can capture scraps of moonlight against a gold thread of sunlight”. In the 1950s, Mitzah Bricard, a former courtesan who became the extravagant muse of Christian Dior, was asked by a lover for her favourite florist. Her reply? “Cartier.” The name has become the stuff of myth.

The precious reality behind that myth is locked up tight in an unmarked, unremarkable grey office building overlooking the placid Lake Geneva, in Switzerland. Its only notable feature – and giveaway that what’s inside may be more interesting than fax paper – is a double set of bulletproof-glass security doors that effectively imprison you in a 6ft by 6ft room with your own breath for a few seconds while an exterior door locks, before an interior one opens. Should someone, somehow, figure out what is located here, this feature is designed to make it especially difficult to sprint out with a few million Swiss francs of diamonds secreted about your person.

This is where the Cartier Collection resides – a physical repository of the jewellery house’s expansive history, the meaning behind that world-renowned name, today one of luxury’s most valuable. “It’s an immense corpus that states who we are and what Cartier is about,” says Pierre Rainero, image, style and heritage director at Cartier. The Cartier Collection is, in various guises, an inaccessible museum, a fabulous lending library (celebrities now often wear antique pieces) and perhaps the greatest multibillion-pound jewellery box in the world. It is not a place to mine for ideas to revive. “It’s not a question of repeating what you did,” Rainero says. “It’s a question of analysing, to understand the leading principles that could project yourself into the future. It’s not taking something from the past to copy it. It’s to understand the principles of what led to some creations in the past, and to make those principles relevant for today.”

The Cartier Collection comprises over 3,500 priceless examples of horlogerie, objets d’art and of course exceptional jewellery: here, ‘priceless’ isn’t a lazy turn of phrase, although each item obviously had a price, many in the multiple millions, like the flamboyant palm-sized flamingo brooch made for Wallis Simpson, Duchess of Windsor, in 1940, which cost Cartier more than £1.72 million to buy back at auction in 2010. Generally, the jewels are the last thing to go when an estate is sold and very few are donated to museums – “Donors give paintings, but they don’t give the jewels,” says Pascale Lepeu, director of the Cartier Collection since 2003. Yet these pieces are priceless now, because each is an exceptional one-off, created for clients and then tracked down and bought back by the house to enrich its understanding of its own history and its ability to show it off to the world. Cartier has staged 43 monographic exhibitions in institutions across the globe since the foundation of the Cartier Collection in 1983 – number 44, exploring the Cartier myth, opens at the Victoria and Albert Museum in April. More than 360 objects will be on display, over 200 of them from the Cartier Collection.

“A Cartier exhibition is also about the evolution of the creative arts, and also the evolution of women” – Pascale Lepeu

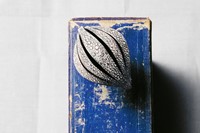

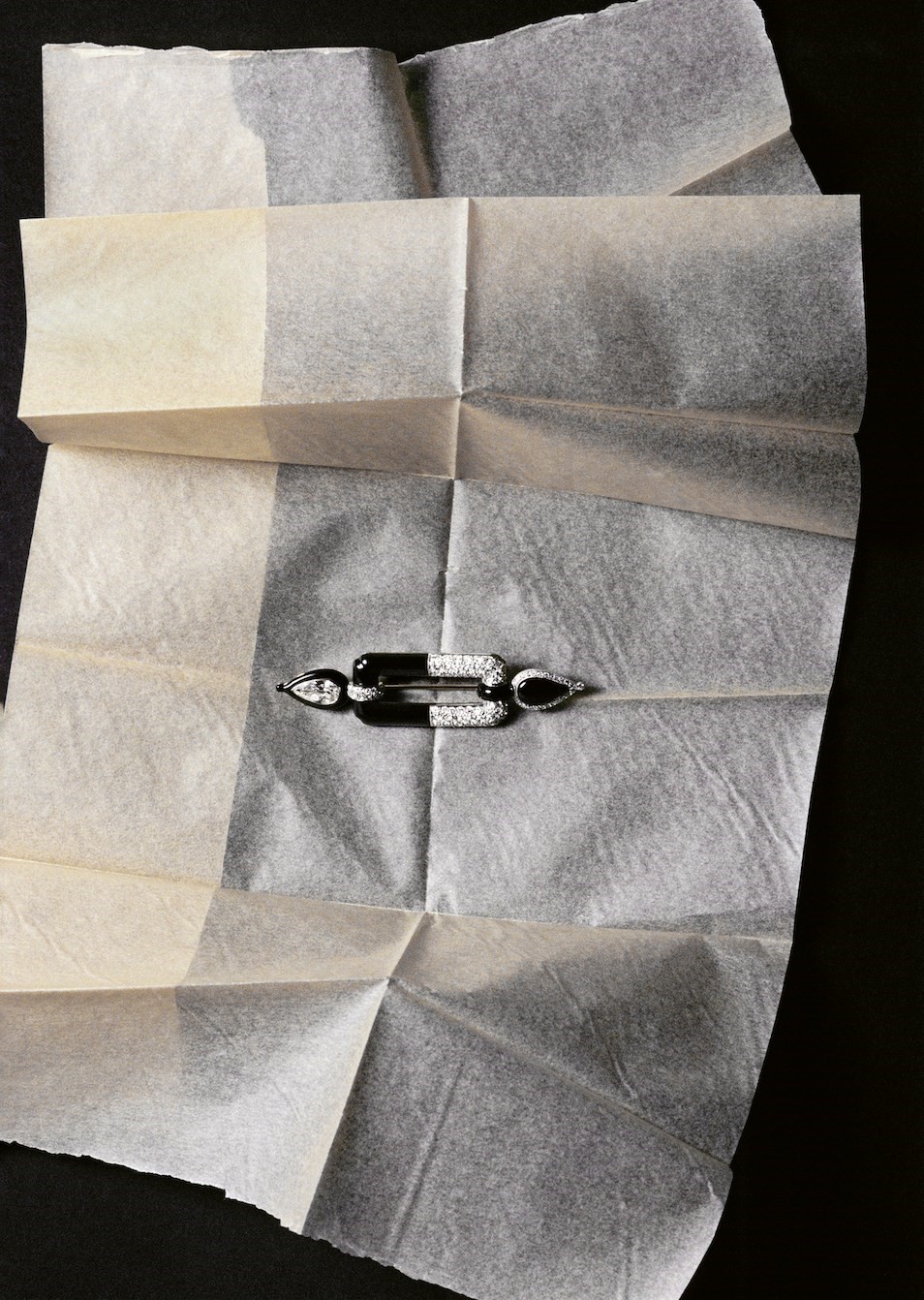

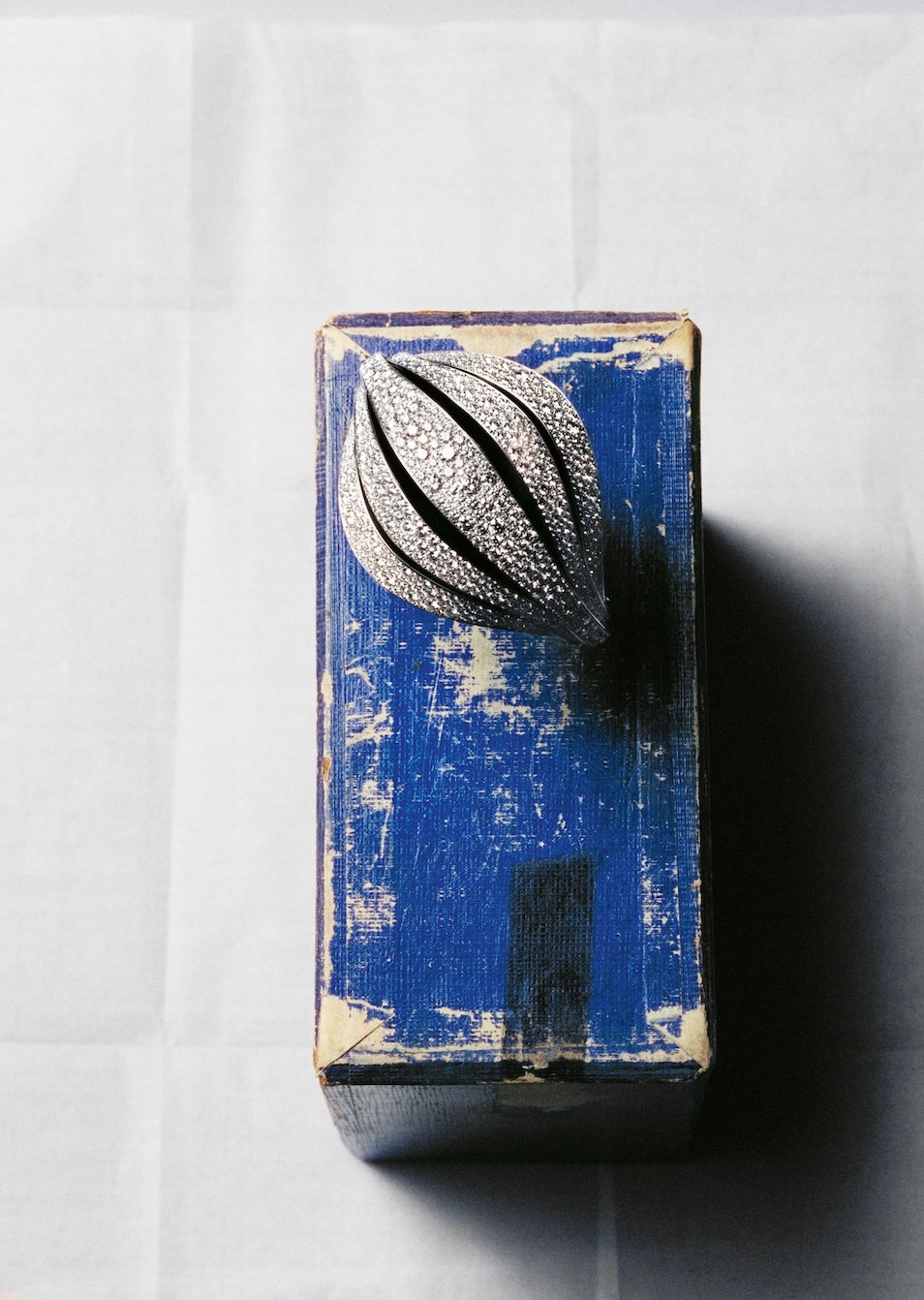

“A Cartier exhibition is also about the evolution of the creative arts, and also the evolution of women,” Lepeu says. She is the custodian of the Cartier Collection: it is in her white-gloved hands that pieces are turned over, clasps opened, gems examined. What you find in her palms is a constant surprise – it could be a 1912 brooch in platinum and white diamonds, known as a stomacher, designed to accentuate the front of an evening gown, or a tiara with panels carved from rock crystal that resemble ice. Both are relics from a bygone age – though neither as bygone as a 1920s brooch inset with a fragment of ancient Egyptian faience. Those pieces of the past, inlaid into modern jewels, were a Cartier speciality of that era, when

Egyptomania was all the rage – the historical fragments are known at the house as apprêts, which figuratively means “without artifice”. It’s reminiscent of a division Cartier operates today, named Cartier Tradition, where antique pieces are sourced, authenticated, restored and sold again on a global market rabid for pieces of the past.

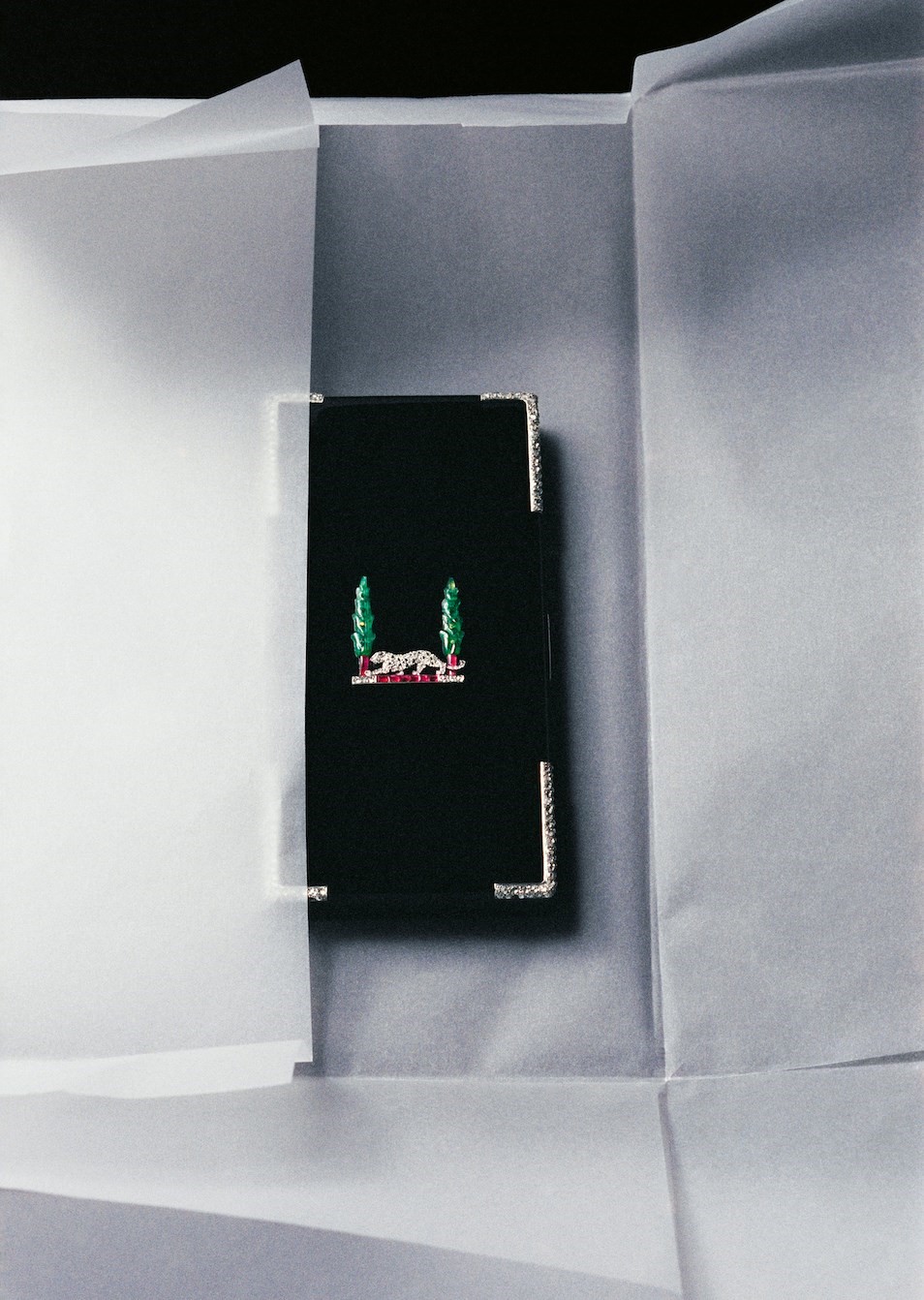

When Lepeu talks of the evolution of the creative arts, it’s because Cartier is an extraordinary mirror of its time. “There is a very specific dimension of Cartier,” Rainero says, “which is linked to that vision and that ambition that our founders had, to promote the artistic dimension of jewellery.” The curved forms of the 1912 stomacher were already falling out of favour when it was made – as early as 1909, Cartier had begun to play with motifs that would become more readily associated with art deco, modernist shapes and contrasts of white diamonds and black enamel or onyx, a characteristic house colour combination to this day. Vibrant coloured stones echoed the remarkable influence of Sergei Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes across the decorative arts. In the 1930s, jewels became surrealistic; during wartime in the 1940s, they twisted patriotic. And Cartier’s cigarette and vanity cases marked a shift in female freedom, from closed-door cheek-pinching to the liberated make-up-wearing, tobacco-smoking flappers of the 1920s. They are all present and correct, a cultural history set in (precious) stone.

What you won’t find in the Cartier Collection, however, are sketches inspiring these extraordinary pieces, or documents working out their technical ingenuity, or receipts for their original sale. Cartier makes a distinction between the terms ‘archive’ and ‘collection’: archives denote paper files – design sketches, receipts, catalogues of pieces made – which have been exceptionally preserved from the house’s founding to today, held in each of Cartier’s original trio of locations. “It’s our definition, it’s not a common definition for everybody,” Rainero says. “I think it was in the Cartiers’ culture to keep information, when we see how precisely, how methodologically, they kept all the information,” Lepeu says. These documents enable the identification of designs – an unmarked piece from the mid-19th century was found to be Cartier when a numbered label, secreted under the plush of its protective box, matched with a serial in the Cartier Paris archive. Cartier harnessed new techniques of photography to record all of its creations from 1907; there are even examples of jewellery forms cast in plaster, like three-dimensional ghosts of existing pieces, dispersed somewhere in the world.

Or perhaps they don’t exist any more at all. The earliest piece in the Cartier Collection dates from the company’s first decade in business – but it’s a rarity. In the 19th century, démodé items would be broken up, the still-valuable stones reset into new designs. Reverence for historical pieces is a relatively new phenomenon – even in the mid-20th century, family jewels were used to create new pieces. The Duchess of Windsor’s famous flamingo brooch, for instance, comprised the calibré-cut rubies, sapphires and emeralds of four simple art deco line bracelets from her own collection, as well as diamonds from one of her necklaces. She even had Cartier reset the 19.77-carat emerald of her engagement ring in 1958 – she wanted the mount to be more modern and opulent. Conversely, history has always been important to Cartier, with designs based on antique examples, references to renaissance jewels or the style of the court of Louis XVI. Books on both existed in the wealth of surviving source materials used to inspire Cartier designers at the beginning of the 20th century, and throughout his career, Louis Cartier, the grandson of the house’s founder, encouraged close study of historical styles, to discover something new.

Cartier became rapidly renowned for its artisan mastery, for physically making extraordinary things. But it was also a master of mythmaking. “Cartier was pioneering in building its image,” says Rachel Garrahan, co-curator with Helen Molesworth of the Victoria and Albert Museum’s exhibition. “It’s a precursor of the global brands that exist today.” One part of the Cartier exhibition focuses on the image the brand has been able to forge of itself, the magic it could imbue its name with.

The name Cartier may be monumental, but it is also personal – it is the name of the family that founded the house and controlled it until the 1970s. In 1847, a 28-year-old Louis François Cartier took over the workshop of his maître, Adolphe Picard, an acclaimed jeweller who had trained the young apprentice from the age of 14. He put his own name over the door and roughly a decade later reached acclaim when the princesses of the court of Emperor Napoleon began to buy jewels from the boutique. The second generation of Cartiers succeeded in 1874, with LouisFrançois’s son, Alfred, taking over: in 1898, Alfred’s eldest son, Louis, became a partner aged 23, the house renamed Alfred Cartier et Fils. Alfred Cartier would have two more sons – Pierre Camille and Jacques – and all three were involved in the business, heading different geographic branches of the house (Paris, New York, which opened in 1909, and London, in 1902, respectively).

Although the Cartier children proved to be savvy businessmen, the eldest seemed the most innovative. Not a designer, Louis nevertheless knew how to spot and harness creativity to project Cartier forwards. He also had instinctive taste: he eschewed the fashionable art nouveau style of the early years of the 20th century, with its focus on glass and silver, considering it bourgeois. Under his watch, Cartier designed pieces that echoed the delicate grandeur and intricacy of 18th-century France – a style that came to be known as Garland, for its swirled forms that resembled the carved boiserie of rococo hôtels particuliers or elaborate lace, yet executed largely in platinum and white diamonds. Louis chose those materials because, to his eyes, they particularly sparkled under the newly installed electric lights of modern homes.

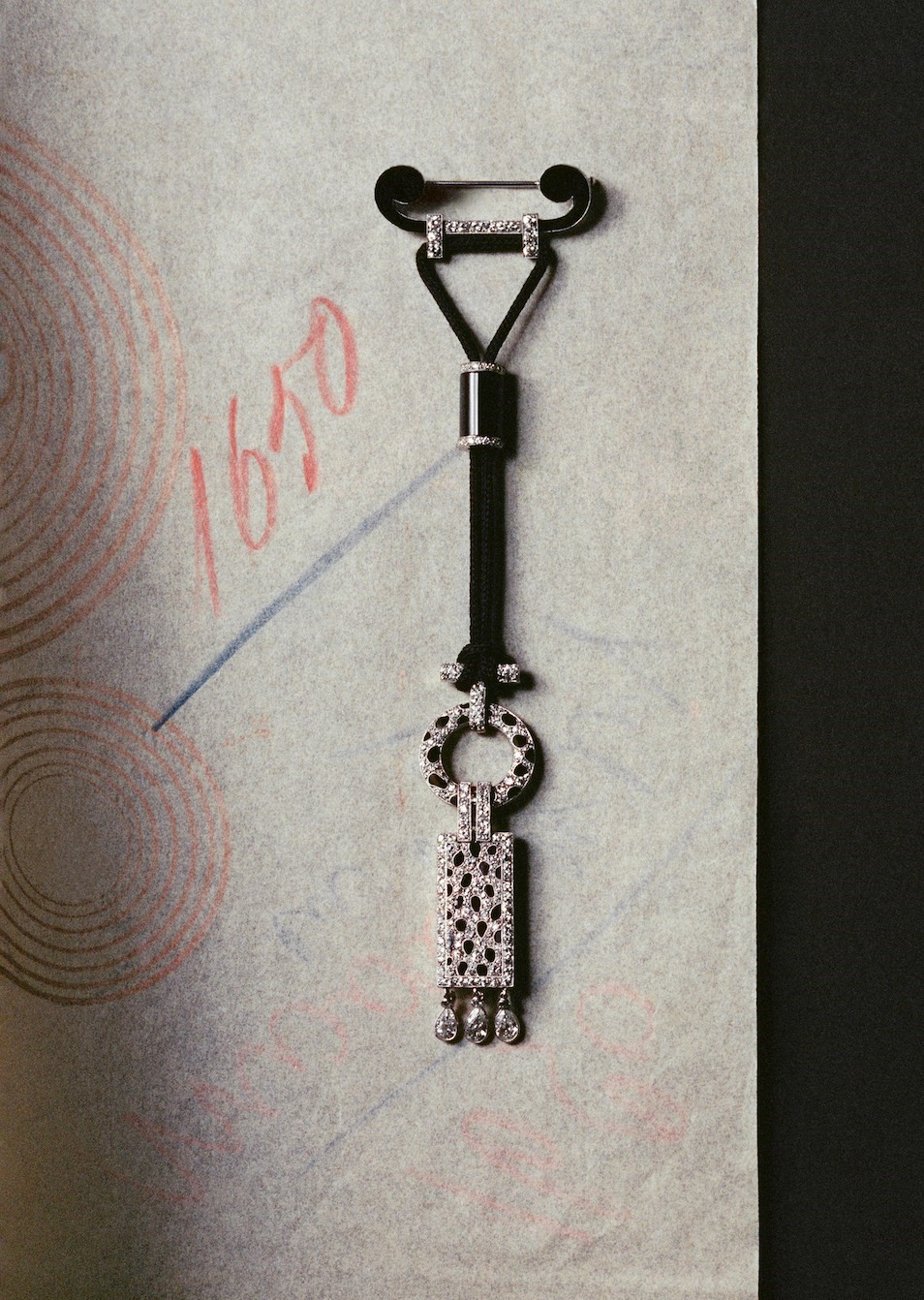

He undoubtedly also had an eye for talent: he discovered Charles Jacqueau – hailed as “the Picasso of jewellery design” and a major contributor to the Cartier style in the early 20th century – when he was installing a wrought-iron balcony on a Paris boulevard in 1909. Charles, 24 at the time, had designed it, and Louis admired the geometric form and modernity. Incidentally, the Garland style that Cartier explored around this time took as part of its inspiration the balustrades of Versailles. And a name most widely associated with Cartier, Jeanne Toussaint – who came to Paris as a courtesan under the ‘protection’ (as it was termed at the time) of a count, Pierre de Quinsonas – was employed by Louis in the early 1920s, after meeting her just before the first world war. Louis, recently divorced, engaged her because of her daring sense of style – but business at Cartier often mixed with pleasure, and the two would become lovers. She was already friends with Gabrielle Chanel and at first co-ordinated Cartier accessories, designing handbags and so-called nécessaires for the upper echelons of society. In 1925, she was handed a larger Cartier division, the S Department, which created practical and elegant objects and accessories that were usually only lightly adorned.

By 1933, Jeanne’s influence was such that she was appointed Cartier creative director that year – the first non-Cartier family member to hold the role, and within the fine jewellery industry, the first woman. Announcing his own retirement, Louis wrote that “Toussaint has a universally appreciated taste”, which was echoed by Cecil Beaton, who in his Glass of Fashion, wrote of her that “no one is more revered among the intimates for her extraordinary taste”. Louis affectionately called her “ma petite panthère” – and although Cartier had produced panther-inspired jewels as early as 1914 (the markings appeared on a watch in onyx and diamonds), the animal’s first figurative appearance was on a cigarette case given to Jeanne by Louis in 1917. Under her watch, it would later perch on emeralds or cabochon sapphires, its body stretched out to span wrists. “This was at the time when women were not independent, times when it was difficult to have a bank account, or to work, without the authorisation of the husband,” Lepeu says. “So this woman, Jeanne Toussaint, had to create a jewel representing independence, power.” The panther has become an enduring, eternal emblem of the power of Cartier too, of its technical expertise as well as creative prowess, its pattern worked in enamels and precious stones. “It’s like a masterpiece, something beautiful. Like Mozart,” Lepeu says.

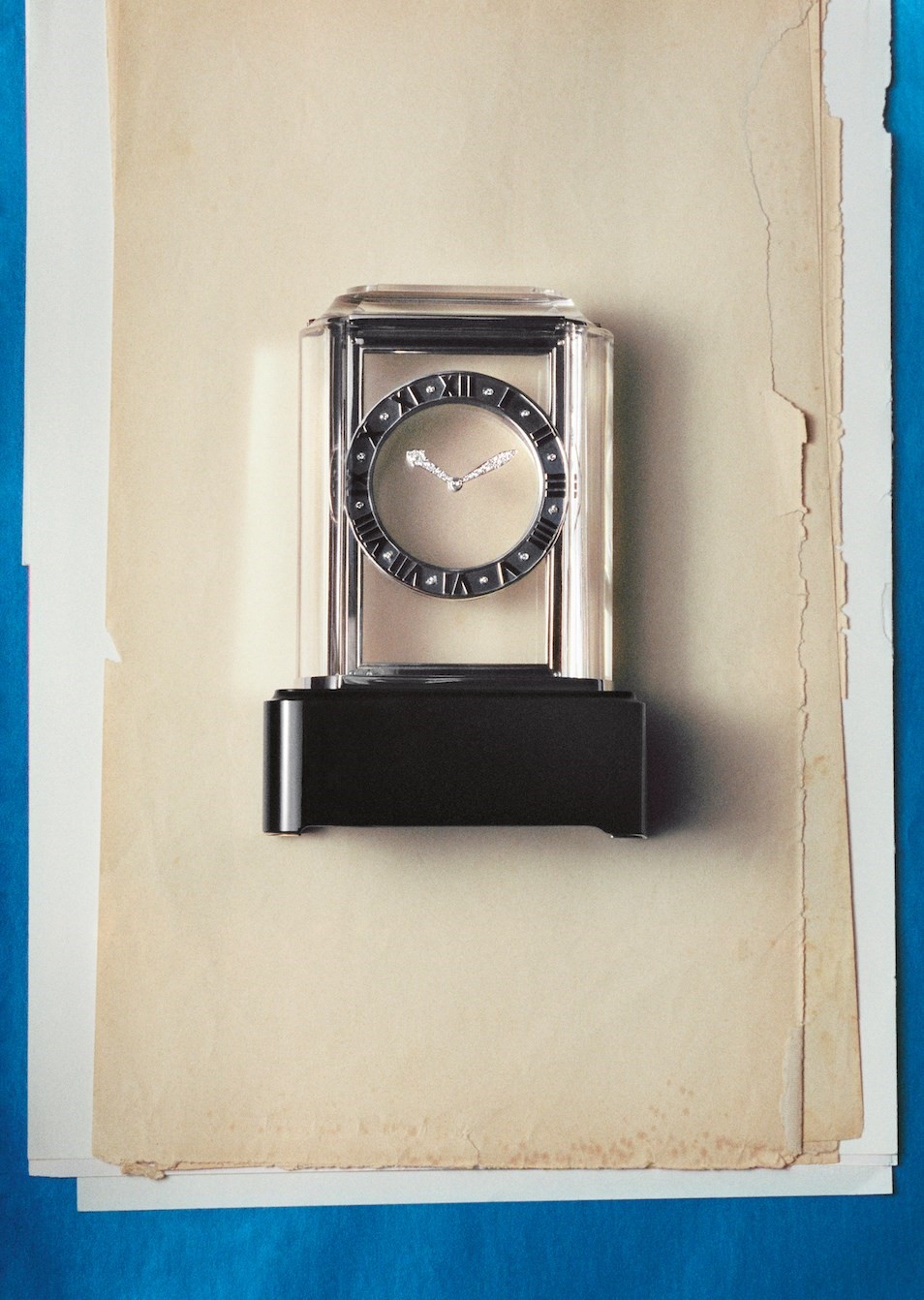

The panther is just one of many hallmarks. Cartier is known for a multitude of emblematic jewellery designs spanning over a century, from art deco to its exotic bestiaries of jewelled tigers and birds alongside the panthers, to the simplicity of a nail twisted around a wrist as a bracelet, designed by Aldo Cipullo in 1971 and inspired, he said, by the painful ‘creative’ act of stepping on one. But to mix jewellery metaphors, Cartier’s ‘Fabergé eggs’ are its Mystery clocks. Suitably shrouded in secrecy, there exist only 100 or so of these exceptionally complex items – “Even at Cartier today, it takes time to produce them. It’s very difficult to produce more than one per year,” Rainero says. The clocks’ name comes from their magically floating jewelled hands, which seem unanchored to any mechanism – the hands are, in fact, embedded in transparent discs, the entire clock face turned by mechanisms hidden in the frame. Originally invented by Jean-Eugène Robert-Houdin in the 19th century, the first examples only had one hand – Cartier was among the first to add the second, debuting the idea in 1912. “You know that, originally, even the sales staff didn’t know how they worked, so they couldn’t tell the client,” Rainero says. “They are masterpieces and considered as such.”

Mozart. Masterpieces. Cartier, again, connects with a wider scope of creative endeavour. It’s not just about displays of wealth but something richer, deeper. “There’s a motto in French,” Rainero says. “‘To know where you go to, you have to know where you come from.’” It’s not only Cartier’s own past that continues to sell its dreams but its cultural position within history that determines its enduring significance.

Cartier will run at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, from 12 April – 16 November 2025.

This story features in the Spring/Summer 2025 issue of AnOther Magazine, which is on sale now. Order here.