Polmida’s new exhibition in Florence looks at how denim can carry the wears and tears of a life, and what these say about the social conditions it is dressed within

There are few other textiles as veritable a social artefact as denim. How the textile can carry the wears and tears of a life, and what these say about the social conditions it is dressed within, is at the crux of Polimoda’s second exhibition of their AN/ARCHIVE series: blue re/volution. “Denim, without the human body inside, is just fabric,” says Massimiliano Giornetti, director of Polimoda and curator of the exhibition. “It only becomes meaningful when it is worn, lived in, and transformed by time.” Conceived as an ‘anti-archive,’ the exhibition is not just about “preserving fashion in glass cases,” but contextualising denim through an interactive dialogue with history, culture, and materiality.

The starting point of blue re/volution is interestingly in denim’s indigo colouring, rather than its materiality. From the sacred mythology of Afghani lapis lazuli to the mantles of Madonna in 15th and 16th century Renaissance paintings, rich tonal blues were historically sanctified. But today, such a deep shade of blue is typically associated with denim and its most common outfit: workwear. “The contrast between the deep indigo of workwear and the lapis lazuli of Renaissance iconography reveals the oscillation between the sacred and the mundane,” explains Giornetti. And herein lies the stake of the exhibition: the multitude of paradoxes denim is pinned between.

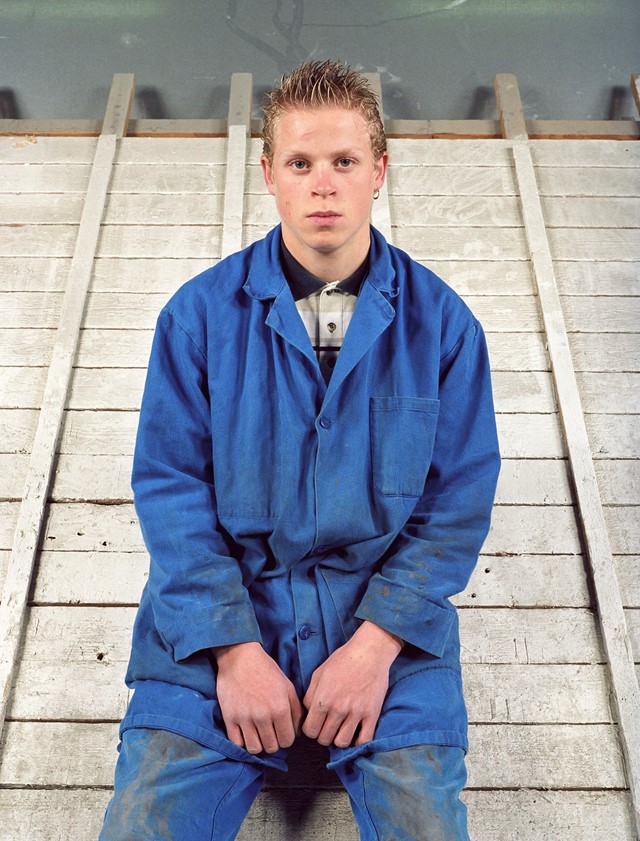

In the (AB)NORMAL Studio designed exhibition space, a selection of iconic garments from the Italian brand Roy Roger’s 6000-piece denim archive are placed face-to-face with photographer Charles Fréger’s probing portraits of students at trade schools, head-to-toe in their workwear blue. Amongst the archival pieces are old Levi’s and Lees, evoking the original denim-clad rebel without a cause, James Dean. Yet if these garments are an expression of personal identity and rebellion, in the photographs opposite, denim “represents a uniform in workwear, and with it an erasure of individuality,” reflects Giornetti.

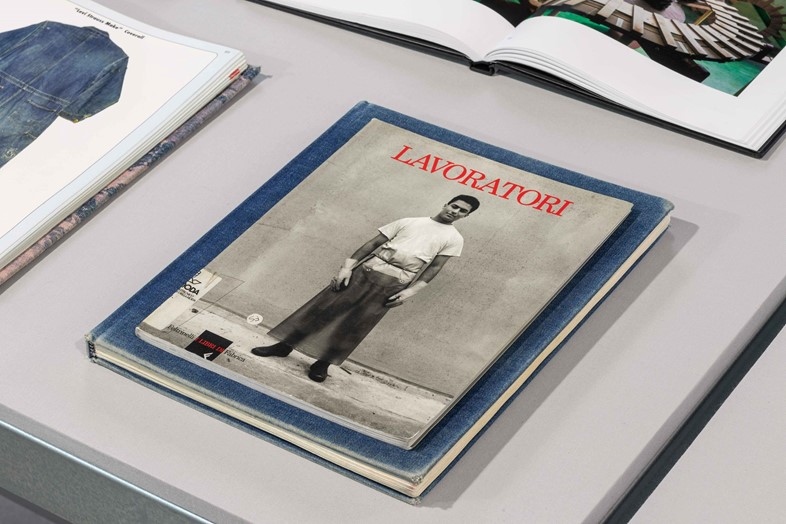

At the opposite end of the space – and separated by a curated selection of rare books on denim which visitors are free to browse – is a large-scale installation, Zurashi/Slipped, by textile artists Rowland and Chinami Ricketts. Large threads, suspended from the ceiling, have been dyed at the couple’s farm, where they grow and process their own indigo, and then organised to form an ikat print. Kinetic and delicate, the installation is a reminder of just how fragile and volatile a molecule indigo is: dyeing can take up to 65 passages to ensure the colour remains. It’s a wonderfully effective contrast with the other sections of the exhibition to highlight the binary between indigo as a precious natural resource and denim as a tough, durable textile.

There are other curiosities raised: how denim, which originated as a humble fabric for labourers, is now an important line in many luxury fashion houses (Calvin Klein was the first designer to present denim on the runway in 1976). It’s also a textile that has historically transcended gender categories, notably with the universal five-pocket jean model. Yet the message pressed through all of these conversations is that denim is an inherently authentic textile. “The first pieces I found in the Roy Roger’s archive had wax marks from miners who worked by candlelight,” reflects Giornetti, “these traces of use were not design choices, but real-life imprints of labour.” Denim can absorb a life, with all its wear and tear and repair – if only we take the time to care for our garments, and the precious ecosystem from which it comes.

AN/ARCHIVE EVENT TWO: blue r/evolution is on show at Polimoda Manifattura Campus in Florence until February 15.